International Men’s Day on 19 November saw me in a packed room in Westminster for the inaugural conference of the Men and Boys’ Coalition (MBC). The MBC, of which I am an enthusiastic member, has been going since 2016, slowly building its voice on a range of issues. It’s most recent policy focus has been on the under-achievement of boys in education.

This was no glossy corporate conference. It was organised (on a shoestring) by volunteers and accompanied by typewritten handouts. But despite the informality of the event, it’s a long while since I’ve been transfixed by every single bit of a one-day conference.

Subsidies, SEN and scouting

Robert Halfon, MP for Harlow and Chair of the Education Select Committee, used his opening slot to tread through the issues for white working-class boys, being careful not to lay the blame on families and parents. Instead he favoured reducing childcare subsidies for wealthier families to provide more for lower-income families. He’d prefer to see the £50m set aside for grammar school expansion used to support disadvantaged pupils, a more affordable approach to youth engagement activities (he prefers the Scouts to the National Citizenship Scheme), and called degree apprenticeships the ‘jewel in the crown’ for technical education.

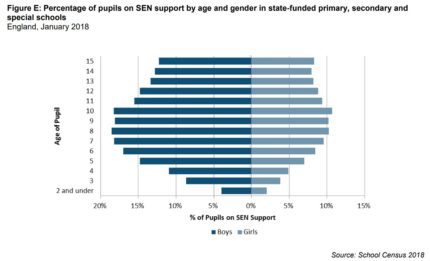

Aside from the now familiar deficits in boys’ attainment through all the key stages of education, my own contribution picked up new insights from last month’s DfE publication, Understanding KS4 Attainment and Progress. Among other things this report calls out two significant contributors to the male attainment gap. The first is special education needs, or SEN, which is a strong predicator of attainment. Boys are much more likely to be classed as having SEN (including statements or school action) than girls (15.2% of boys compared with 8.7% of girls).

The second key contributing factor is parental expectations. The report highlights that, for girls, half of parents thought it was very likely (50.4%) they would go to university while 3.2% thought it was not at all likely. In contrast, for boys, 39.0% of parents thought it was very likely they would go to university and 9.5% thought it was not at all likely. Parental perceptions of the likelihood of going to university were also found to be a strong predictor of attainment.

What makes the statistics on the gender gap so interesting is that they compare pupils from the same families, with the same demographics, going to the same good or bad schools and being taught the same curriculum by the same teachers.

What is going on here? What are we getting so wrong for boys that we have 38,000 missing 18-year olds boys progressing to higher education?

Under-preparation and discouragement

Dr Erik Cownie, a researcher on the Ulster University’s ‘Taking Boys Seriously’ project, started to stitch together some answers from their action research. He pointed to the way that some boys construct their masculine identity, a lack of understanding of class context and deficit-model thinking which pathologises low attainment.

Ulster’s research focuses on boys’ low motivation, falling behind and never catching up in literacy and numeracy, “woeful” under preparation for key transitions such as from primary to secondary, and higher-potential boys being fearful of being socially alienated from non-attaining peers. He cited “not just the absence of encouragement, but the presence of discouragement” – for some boys, noting that one or two GCSEs is no failure but a “fantastic achievement”. The curriculum assumes engagement but working-class boys have a real sense of disconnect between the curriculum and their lived experience.

Asked what one thing would make a difference, Dr Cownie didn’t hesitate: “Relationships. Boys are screaming out for a trusting adult relationship, someone to take an interest, value them and love them.”

Role models and case studies

Sonia Shaljean, founder of Lads need Dads, devotes her charity’s work to providing male role models to fatherless boys. Boys on her programmes participate in multiple activities from cooking to bushcraft survival training. They work with 11 to 15-year-old boys to deal with the anger, depression and feelings of worthlessness that typically come from being without a father. She introduced us to three boys from her programme who spoke movingly of the difference it had made to their lives. In short, they now had purpose.

Syed Najibi is a young refugee from Afghanistan. Aged just 13, he endured a harrowing journey to the UK only to find that “Women (refugees) are seen as vulnerable, children are seen as cute. But men are seen as a threat.” This quietly spoken young man did well at school and is now doing an Access to HE course to prepare for an engineering degree. But he won’t be eligible for a student loan and envisages a hard road ahead to get his degree.

At 6’2″ and 21 stone, burly Somali-Londoner, Mahamed Hashi, doesn’t look like someone to mess with. Yet a shocking photograph reveals the zigzag scar on his shoulder following a shooting that nearly left him dead. In Lambeth, he says, “education attainment is a luxury compared to survival”. His take on the much-reported knife crime in London this year is from front-line experience. “Asking a boy to put down his knife is no good if you don’t change the context of violence. It is a response to fear,” he says.

Men “not that into teaching”?

Dutch-born psychologist, Professor Gijsbert Stoet from Leeds Beckett University, cited a successful Dutch TV campaign that translates loosely as: “do you allow your boy to be enough boy?”. Professor Stoet is clear in his view that there should be more “boy books”, more physical activity in class, somebody to tell them what to do, and recognition that their executive functions and independent thinking skills develop later than girls.

“Boys are too often seen as deficient girls,” he says bluntly. He isn’t convinced that the lack of men in the UK’s teaching workforce is a problem, pointing out that Saudi Arabia has one of the worst “boy problems” and in a country where boys are taught by men and girls are taught by women. “Males are just not that into teaching” he suggests.

On the other hand, David Wright, one of the just 2% of males in the early years workforce in the UK, believes that children have the right to be cared for by men and women and that more equality provides a better chance of meeting all children’s needs.

On the prevalence of homophobic bullying, Oliver O’Donohoe from Spectra CIC told how he’d had schools refuse to take a guest assembly on homophobia because it would be inappropriate. “The fact you have boys getting pushed downstairs for being insufficiently masculine, that’s what’s inappropriate,” he said.

Kathryn Albany-Ward, the mother of a colour-blind son, campaigns for the 8% of boys who suffer from colour blindness – it’s only 0.5% for girls. With an average of at least one colour-blind pupil in each school class of 30, and less than 25% of colour blindness diagnosed, she advocates passionately for the return of the simple eye test which would help, and for the exam boards to ensure that exam papers don’t disadvantage mainly male colour-blind candidates.

Raw truth and next steps

And finally, former mental health tsar, Natasha Devon, said simply that “asking men to talk more is as crass as asking fat people to eat less”, continuing that “we need to change the narrative from ‘men don’t talk’ to ‘we aren’t listening'”.

Devon was one of several of the speakers who also contributed to a 14-point policy brief launched by MBC at the conference. The brief includes recommendations on everything from ‘take your son to university days’ and targets for GCSE attainment, to the need for more male teachers and calls for a dedicated academic centre to explore issues that disproportionately affect men and boys.

This was a day of raw truth about the trauma, loss, violence, stigmatisation and institutional deafness to boys’ and men’s realities. With the problems laid bare in moving and convincing testimonies, solutions still come only in soft-focus. My question remains: why is there no national, focused policy action to address the issues for boys and young men that play out so starkly in underperformance in education?

Because society portrays men as the winners and the dominant

When boys underachieve, they themselves are blamed for it, whereas when girls underachieve it is said to be due to sexism. When girls and women have eating disorders then idelised body images are to blame; when boys and men take stereoids to get bigger muscles, then it is seen as a chioce they have made themselves. It’s the same in many areas. The narrative has been that females are affected by sexism but males freely make choices. This lie has persisted for way too long.

@Najma is bang on here. But how to address?