A recent survey of all UK universities indicates that 54 per cent of them are accredited living wage payers and when combined with those paying the voluntary living wage this rises to 82 per cent.

There is little difference by mission group. A third of universities do not require contractors to pay the living wage. There are 22 universities in the UK who do not pay a living wage to their directly employed staff.

Over the past few years I have spent my Christmas and New Year break reviewing which universities pay a living wage. Sad maybe, but I think the living wage is an important indicator of a university’s social purpose not least around the burgeoning “civic university” agenda. Some do not agree with that notion, arguing that it is too simplistic, but frankly I disagree. I think it is a simple moral argument that if you claim to be civic, or celebrate your social purpose in other ways, treating your lowest paid employees with dignity by paying them a living wage is a baseline requirement. Put simply, you can’t be civic if you don’t pay a living wage.

A real living wage

The living wage is the amount that someone needs to live in dignity. The Living Wage Foundation calculates this to be £12.00 an hour (£13.50 in London), according to the cost of living, based on a basket of household goods and services. In contrast the statutory minimum wage for those over the age of 23 is £10.42 (rising to £11.44 in April 2024), which the government confusingly brands as the “national living wage”.

Employers – including universities – have adopted the language of the “voluntary living wage” where they claim to pay the level determined by the Living Wage Foundation but are not accredited in doing so. This contrasts with the “real living wage” which is when an employer is accredited by the Living Wage Foundation as paying the living wage which also covers third party contracted staff such as outsourced catering, cleaning and security services.

This year, with the support of a community of practice on higher education supported by Citizen’s UK, the analysis covers the 141 members of Universities UK (excluding the University of Gibraltar). As of 1 November, the Living Wage Foundation had accredited 73 universities and through our process we identified a further three that are in the process of accrediting (or are accredited through a parent organisation). This means that 54 per cent (76 of 141) of universities are accredited living wage payers, which as a recent blog on Wonkhe noted is higher than other anchor institutions including local authorities (28 per cent) and the NHS (17 per cent).

For those un-accredited universities we looked at their websites to see if we could find any evidence of paying a voluntary living and if not, we sent a freedom of information request asking two questions: first,does the university pay a living wage to its employees and second, does it require contractors to pay a living wage to its staff. In total we issued 61 FOIs and got responses from 57 (including two in the process of accrediting). 22 (16 per cent) of universities confirmed that they do not pay a living wage to their staff or require it of contractors. In combination with the desk research we identified 39 (28 per cent) universities who pay the living wage to their employers, but only eight confirmed that paying the living wage was a requirement for third party contractors (it should be noted not everyone responded to the question on contractors, but 18 did confirm it is not a requirement).

Good news and bad news

So what to make of this data? First it is excellent news that 82 per cent of universities in the UK are paying the living wage to their employees and this fact should be celebrated. Since starting this work, there has been an increase in accreditation with the Living Wage Foundation. For example in 2019 just 38 universities were accredited, in 2021 there were 52, in 2022, 63, and today 76 – literally a doubling in just five years.

While this is a positive trend and the overall figures for the combined real and voluntary living wage are high, it is important to highlight the 22 universities that refuse to pay a living wage. So far in this exercise I consciously shy away from naming and shaming, but they know who they are and should really reflect on whether it is appropriate to be exploiting your lowest paid staff in a cost of living crisis, even with the acute financial pressures that universities face.

Second is the fact that there are at least 40 (28 per cent) universities that do not require contractors to pay the living wage to their staff. The same moral argument applies in my view to these individuals as it does to direct employees. Indeed this is why accreditation with the Living Wage Foundation is so important, as it provides both transparency and accountability when it comes to paying the living wage. Additionally, it demonstrates civic leadership encouraging other employers in the locality to follow suit.

When discussing this topic with colleagues I often hear that universities are worried about implementing such requirements. There are two concerns. The first is the process of accreditation with the Living Wage Foundation and the second is the impact it will have on contractors. Neither are barriers – as many can testify the Living Wage Foundation is very pragmatic in the time period it takes for contracts to be living wage compliant and are very happy to discuss this with any potential universities. As to contractors, the large national providers are very familiar with the living wage as they are more likely than not to have customers in place who already require paying the living wage.

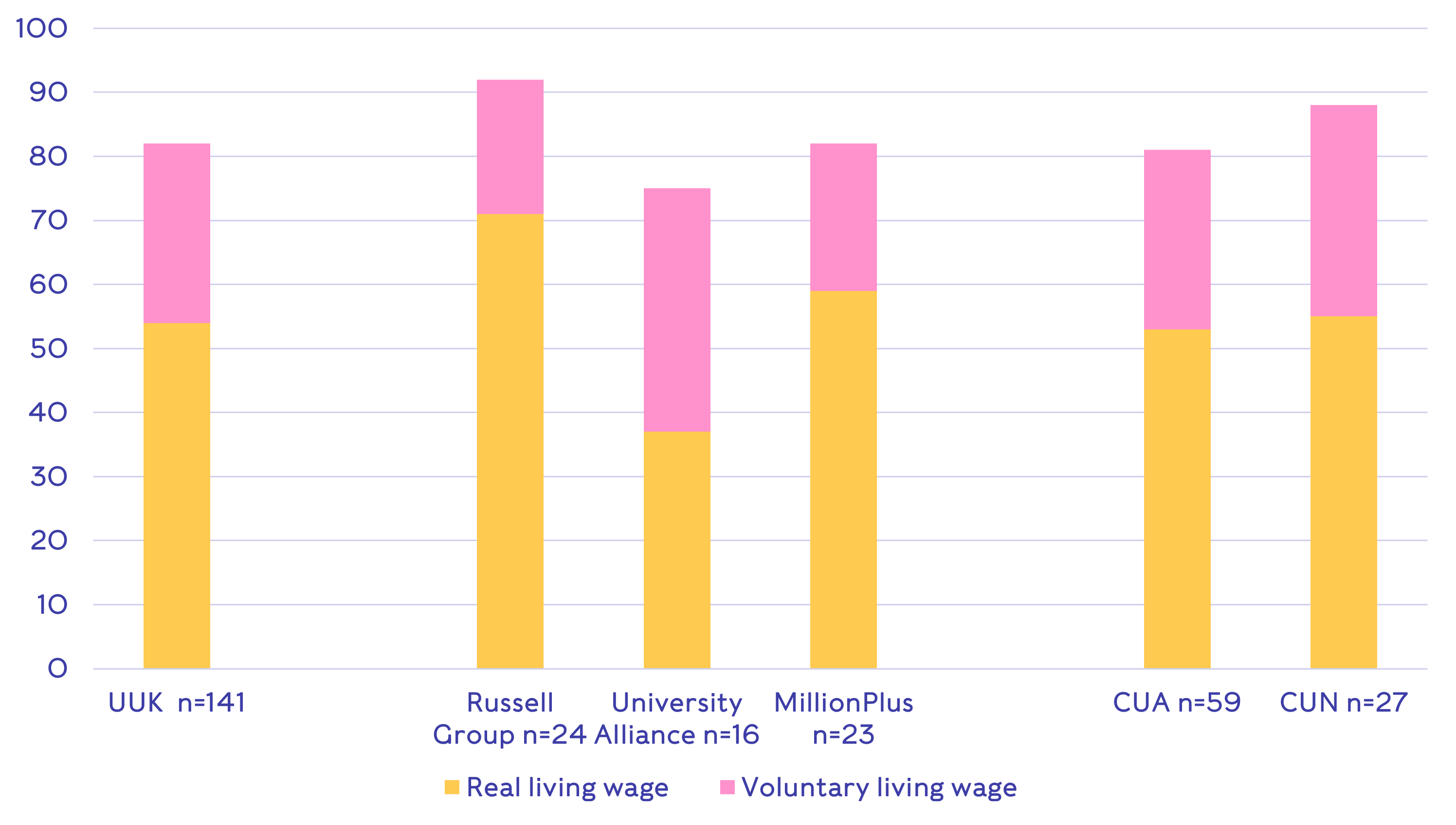

The final observation, is the lack of variance between different types of universities, as illustrated below. Four out of five (82 per cent) of universities in the UK are paying either the real or voluntary living wage, with the Russell Group having the highest rate (92 per cent) and the University Alliance the lowest rate (75 per cent). Interestingly, 89 per cent of those 27 universities that have published a Civic University Agreement are paying the real or voluntary living wage indicating that there is no longer evidence of civic washing, which is again to be celebrated.

Figure: Proportion (%) of universities paying the real and voluntary living wage by selected mission groups. The Aspired Civic University Alliance (CUA) refers to those universities that made a commitment to develop a Civic University Agreement in 2019. The Civic University Network (CUN) are those 27 universities that have published agreements on the CUN website, as of 1 November 2023. There are some universities who did not make a commitment in 2019 but have published an agreement.

So as we enter a difficult 2024 with real concerns about the financial viability of higher education in the UK, let’s not lose sight of those within our communities on low pay. Whether directly employed or via a contractor, cleaners, security, catering and other staff deserve to be paid a living wage.

Perhaps as a sector that should be our new year’s resolution – why could we not aspire that all 141 UK based universities are accredited living wage payers by the end of the year? That would be a truly civic contribution to the social purpose of higher education in the UK.

The author would like to thank Tim Hall, Ella Rechter, Ed Heery and Tom Levitt for their help with the FOI requests. You can find out more about Living Wage accreditation from the Living Wage Foundation.

Name and shame time!

It would be good to mention unions which are often involved in organising for the RLW, and for sustaining and improving pay and conditions beyond these commitments, but aren’t mentioned once. Locally at Durham, UCU has pushed for RLW accreditation for several years and the university has finally committed to this at the start of this academic year.

My WP applicants would like to know how potential choices treat employees such as their parents (and I’d like to be able to tell them).

Will 2024 be the year that Citizens U.K. switches to a suggested donation model for university living wage accreditation? The organisation can easily afford it. The latest accounts show a surplus of £1 million and significant assets. In comparison, City of Sanctuary ask organisations with income of £500k pa to make a donation of £250 for accreditation. Why ask publicly funded organisations for more than this?