Theresa May’s legacy.

You may feel that this could be better managed simply by setting a bin on fire, but it appears that parts of the government have alighted on the Augar review as a fitting cap for a genuinely epoch-defining premiership.

Cast your mind back to an overcast day in February 2018, with the stars of the political and media firmament on glittering display poised in front of a shiny glass wall in Derby College. The “major review” – originally pre-briefed at the previous years’ conference (the coughing, letters falling off the backdrop conference) was originally devised as a decisive response to the 2017 “youthquake”. The (imagined) spectre of thousands of young people making a decision to vote for (oh) Jeremy Corbyn on the strength of more money in their own pockets had buried its way into the collective Conservative psyche.

Something must be done!

The original something that somehow needed to be was done saw billions of pounds spent at conference on the long promised uplift to the student loan repayment threshold. The youth did not flock to “strong and stable”, so the originally trailed review – subject of innumerable speculative phone calls to the DfE press office – finally made an appearance.

It took the summary dismissal of review sceptics Jo Johnson and Justine Greening to bring it about. Two largely sensible, well-liked ministers faced a return to backbench life for their opposition to this – Theresa’s day of glory in Derbyshire.

The best to be said is that we all got to discover the joy that was Philip Augar’s superbly researched and written books on banking regulation, and to re-acquaint ourselves with the speeches of key panel member Alison Wolf. The latter appointment, and the news that the review would cover all post-18 education, made the early running in sector speculation. Two largely complementary sectors prepared for war. Nearly nobody noticed the requirement that any proposals must keep the principle of graduate contributions, and keep the direction of deficit moving (according to eternal Treasury diktat) downwards.

Damian Hinds’ early line through all this was differential fees. For a wannabe populist he does struggle with actual popularity.

Remits, revisions

The remit saw an interim review from the independent (Augar-led) panel sometime in the autumn of the same year, feeding in to a full DfE authored report in mid-March of the next – both, it was hotly rumoured, linked to major fiscal events (the Autumn Statement and Spring Budget). The initial impression was a stitch-up – the panel an unconvincing independent gloss on an in-house botched job.

Of course, there was never going to be a solution to the problem the review defined. No retail offer could match the momentum of “pay nothing up front, and nothing later (in innumerable easy instalments of nothing)”. Blending in the separate and poignant woes of the further education sector just complicated things further.

The independent report was – as independent reports often are – delayed, and this delay began to look more sensible as it emerged that the Office for National Statistics had concerns about the treatment of student loans in the national accounts. A rash of committee reports (and the sterling work of Andrew McGettigan), spread out over the spring and autumn of the extended parliamentary session, had prompted statisticians to reappraise the idea that the finance system somehow didn’t cost any money until today’s expected Brexit delivery date of 2034.

Following advice from Eurostat, the balances were shifted, with the costs of write-off shifted to the point of loan issue. The current system suddenly looked as expensive as it always had been, and the idea of lowering fees contributing to the reduction of a deficit became a bad joke by mid-December 2018.

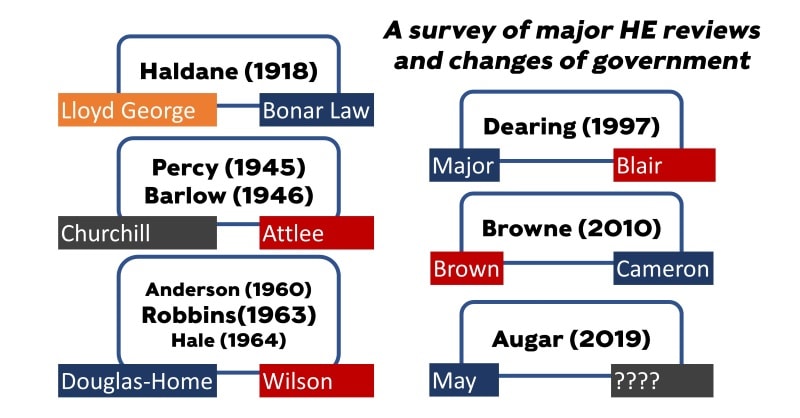

The curse of the major review

And the leaks – oh, my word the leaks. Three Ds to be eligible for a loan. Six thousand fees. Six thousand plus extras for the canonically expensive courses. Every bad idea in higher education funding policy trotted out for a weekend Times dissection. Selective leaking hyped a range of worst-case scenarios for questionable policy benefit. Sam Gyimah relied on Wonkhe modelling of the latest briefly-flown kite. There were no rumours or leaks about student maintenance or the cost of living.

Entertainingly, Chris Skidmore – like he, a mere universities minister, gets to have a say – has taken positions on these ideas. Sensibly, three Ds is a no, and for sound access and participation reasons. Only in this government would a responsible minister be completely frozen out of policy development. He deserves more attention.

The other governmental bad joke – that a beneficial and consensual Brexit would be delivered by 29 March 2019 – also stopped being funny at a similar time as the review did. Augar’s deadline shifted from March to May to June. The review adopted his name as parallel DfE work was downplayed.

And here we are – with May on the point of being forced out the one jewel for her crowning legacy that aides could identify is this delayed, unwinnable, and unanswerable search for an answer to a question that was never really posed. And the curse of the higher education review looks set to strike again.

Formal reviews are far from the only or even the major way that government policy on HE has changed direction significantly. The White Paper on Technical Education in 1956 (under Eden) that created the CATs (and the forerunner of the CNAA) and stratified the local authority sector, the introduction of the ‘Binary policy’ and the creation of the Polytechnic sector in 1966 through a speech (Crosland under Wilson) and a subsequent White Paper, and its abandonment from 1988-92 through White Papers (under Thatcher and Major), the James Report on teacher education in 1972 (under Heath), and the devolution of government… Read more »

Why is it taken as a given that hard thresholds or rationing of places is a bad idea? You can’t just wave your hands and intone ‘participation’ if you’re trying to convince rational external observers who are not professionally motivated to maintain the status quo.