It makes sense that the “producers” of higher education have always been more interested in the value of student tuition fee loans than they have been in the subsidy attached to those loans – or indeed who that subsidy gets allocated to, and when in a graduate’s life it manifests.

But it has always seemed odd to me that we endlessly debate the maximum level of tuition fees, while leaving what students get for that money – and what therefore students need to pay more for – largely undebated.

At the same time, it seems daft that the sector tends to be much more interested in the level of funding for, and unit of resource of, undergraduate study, than what the state both requires and assumes that that money will be spent on.

Take student financial support, for example.

In its response to the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care, the section on narrowing the gap in participation rates says the government will set an “expectation” of universities for support in areas such as bursaries and affordable year-round accommodation.

Throughout the pandemic, students were repeatedly told that their university would help with costs – refunding accommodation fees and extending hardship funds by re-spending premium funding designed for different purposes.

In his responses to multiple questions from backbenchers on the present cost of living crisis, universities minister Robert Halfon says that student premium funding “complements” the help universities should provide through “their own” bursary, scholarship and hardship support schemes.

On a page on the Department for Education’s blog on supporting students with their living costs, the government goes further – here readers are told that, through those student financial support measures, universities are “responsible” for ensuring students who need help get the support they need.

And despite several years of a predecessor organisation encouraging universities to prove that bursaries had an impact on outcomes, the Office for Students (OfS) was only too keen to point out that well over £300m was being promised by universities in financial support through its then new regime of access and participation plans in 2020.

If there are alumni around donating or bequeathing cash to go to hard up students, I’ve nothing against the odd institutional bursary or scholarship – although we do have to bear in mind that it’s usually the richest universities, whose students collectively have the least need for such help, that get the lion’s share of the cheques.

But beyond that, I find the idea of a system that expects universities to spend a penny of tuition fee income on student financial support to be morally questionable, fundamentally unfair and an example of how a claim for institutional autonomy has been turned against the sector and its students.

Policy principles

Just over nineteen years ago, the higher education minister charged by Tony Blair with getting “top-up fees” through Parliament established a couple of helpful policy principles on maintenance at the same time.

The first was Charles Clarke’s aspiration to move to a position where the maintenance loan was no-longer means tested and made available in full to all full-time undergraduates – so that students would be treated as financially independent from the age of 18.

That was never achieved – unless you count its revival and subsequent implementation in the Diamond review in Wales some twelve years later.

Having just received results from the Student Income and Expenditure Survey (SIES) the previous December, Clarke’s second big announcement was that from September 2006, maintenance loans would be raised to the median level of students’ basic living costs:

The principle of the decision will ensure that students have enough money to meet their basic living costs while studying.

But something else was introduced in the package of concessions designed to get top-up fees through. As was also the case later in 2012, the government naively thought that £3,000 fees would act as an upper limit rather than a target – so Clarke announced that he would maintain fee remission at around £1,200, raise the new “Higher Education grant” for those from poorer backgrounds to £1,500 a year, and would require universities to offer bursaries to students from the poorest backgrounds to make up the difference.

It was the thin end of a wedge. By the end of the decade, the nudging and cajoling of universities to take some of their additional “tuition” fee income and give it back to students by way of fee waivers, bursaries or scholarships had resulted in almost £200m million being spent on financial support students from lower income and other underrepresented groups – with more than 70 per cent of that figure spent on those with a household income of less than £17,910.

Seen it in you one too many times

Plenty of people patted themselves on the back, but the problem always was that in our stratified system, the old Office for Fair Access (OFFA) was mainly charged with overseeing effort rather than attainment, checking promises rather than results, worried more about access than outcomes, and when it did concern itself with impact, tended to be pleased when a provider’s figures moved gingerly in the right direction without being too worried by overall inequality between providers.

A fundamental manifestation of that unfairness always was that while everyone was broadly expected to pour a percentage of “additional” fee income into student financial support, the fewer students from poorer backgrounds you had, the more generous you would look. Universities were repeatedly told to allocate what was needed – without the overall system properly bothering to ensure that each university had enough to meet the need.

Naturally, because “we know best” and nostrums like “institutional autonomy” were advanced by richer universities as allowing support packages to be “designed around the needs of our students”, the idea that a sum of money should be inefficiently redistributed around an individual university rather than around the country became de rigueur.

Hence in 2010 David Willets’ announcement on £9,000 fees was accompanied by a doomed sop to his Lib Dem boss – a £150m national scholarship programme, targeted on bright students from poor backgrounds that required “match funding” drawn from universities’ tuition fee income. Guess which universities were able to offer the most help, and why.

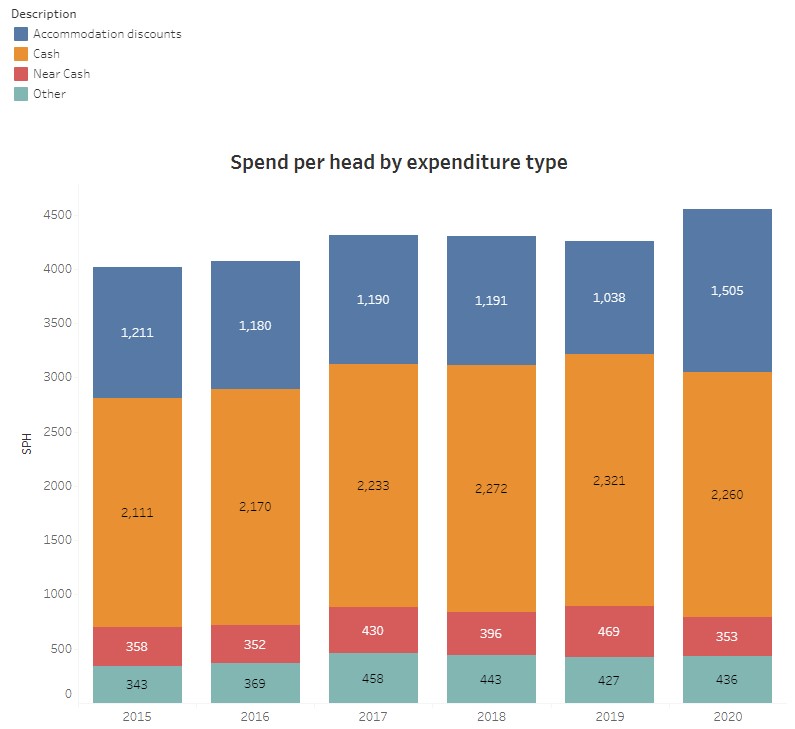

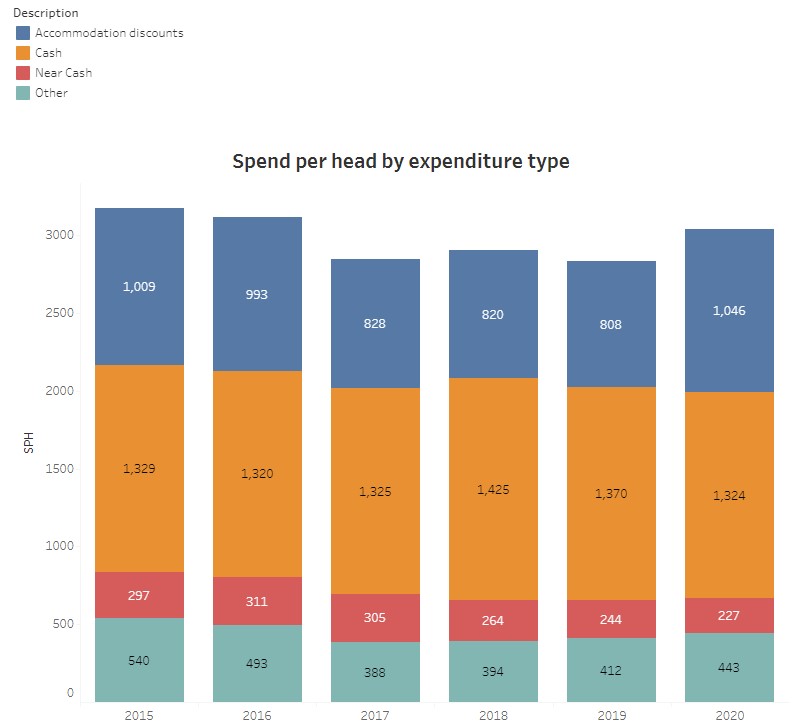

The deep inequality of this kind of student financial support around the sector persists today. In these OfS figures, if you calculate the value of student financial support and divide it by the number of students in receipt of it, the Russell Group averaged £4,554 each in 2020 – £2,260 in cash.

By contrast, providers that were polytechnics until 1992 averaged just £3,040 – and of that, just £1,324 was in cash.

The upshot is that despite claims that providers “know” best, the system is one where financial support is based not on need, but on the number of other students at your university that need it.

And as the state comes to depend on the intervention to cover its lack of doing so, students from poorer backgrounds incur more debt, get less support with their day-to-day costs, and get less spent on their education. How is that fair?

There’s something in my eyes

Throughout the 2010s, gentle pressure was placed on providers to ease off on student financial support, with a focus on bang replacing a focus on buck with successive regulatory and monitoring regimes.

But that period was also accompanied in the middle of the decade by a big-ish bump in the maintenance loan – paid for by Chancellor George Osbourne not having to declare the costs associated with the loan scheme’s progressive features when doing the nation’s accounts, resulting in more pounds in the pocket and better looking finances.

It’s not a stunt that that can be repeated today.

Where we are now is in a state radically retreating from the Clarke principle – one that will allocate almost £2,000 less than Wales will in living costs loans to the poorest students this September, and one that has the gall to publish an equality impact of its own changes to the maintenance scheme that shows “a negative impact for students with and without protected characteristics”:

This is because a 13.7% increase would be required to maintain the value of loans and grants for living and other costs in real terms using the 2020/21 academic year as a baseline, as measured by CPI, due to the recent spike in inflation. Therefore a 2.8% increase in maximum support for 2023/24 will not restore the erosion in purchasing power since 2020/21 and is unlikely to prevent a further erosion in purchasing power by the start of the 2023/24 academic year.

The section in the analysis on the rationale for a maintenance system even reminds us of the dystopian alternative, without noticing that its own figures from November show one in for students taking on the extra debt that it says would represent a failure.

Government intervention is needed because a private sector led credit market for student finance would not work: students would not be able to borrow, partially or fully, the money they need to cover the costs they incur during study and repay the lender once they have graduated and started earning an income.

We are bound by all the rest

Some say the system we have now is fundamentally fine – that it is tweaks rather than radical reform that are necessary. The basic idea – that the bulk of state funding for things other than research is delivered through flat loans for tuition fees, repaid on an income-contingent basis, has, it is said, worked well.

Above all, they say, contrary to the doomsters that claimed that £9,000 fees would mean “Opportunity Blocked” or “Access Denied”, expansion has been encouraged, and opportunity has expanded.

But now, without the “fiscal illusion” of the financing of higher education’s great expansion around to spare us from making the case for its costs, we are stuck – with a frozen unit of resource, more and more being expected of that resource, less subsidy of it through higher and longer repayments of student loans, and less and less in real terms in the pockets of students.

What kind of expansion of opportunity is it when those who are now afforded it pay much more for much less?

It is becoming pretty clear that as the maintenance loan declines in value, more university money will need to go into student financial support in coming years – that’s certainly the direction of travel over student premium funding, for example.

But imagine the Access and Participation working groups in the coming weeks. For a start, many of the members of those groups stand to lose staff or even their own jobs if we pivot back towards cash rather than other types of support.

And in addition, they have a few years of “what works” evidence, when the efficacy of bursaries is harder to prove when the state’s retreat on its end of the bargain has accelerated so much in this space.

There will, just below the surface, be a lot of noise and bias in the decision making, and even more postcode lotteries over the help students need in the outcome. Everyone will mean well – but when there isn’t the money to replace state decline in the value of maintenance and keep up spend on outreach and support all at once, something (or more likely, someone) will have to give.

Universities will be in an invidious position – but it’s arguably one of their own making. When you say you want £9,000 to spend how you see best, you think you’re gaining control. But what you lose when everything becomes your job to fund can be much more than you gain – and it’s students that pay the price.

Good things going

Maybe it will take a while for an incoming Labour government to change course, not least because the stealth changes to the loan scheme mean the RAB charge is now so low as to make it almost impossible to deliver the Corbyn pledge on free fees.

And maybe there does need to be one of those “long grass” reviews on tuition, places, courses and skills – perhaps linked to Starmer’s drive for devolution. But there should be no long processes or extended reviews on maintenance – which is after all about basic human decency, not some “nice to have”.

And nor should the sector get too excited about the swapping of some loan for grant for the poorest, when it’s the poorest whose labour market outcomes mean they’re least likely to pay that portion of the loan back anyway. As the Augar review noted:

The cost to the taxpayer of replacing loan funding with grant funding depends on the level of loan repayments that would have been made. As earnings tend to be lower for graduates with lower prior attainment and from disadvantaged backgrounds, that level of foregone loan repayments from students from low-income households is likely to be low.

Step one for a new Labour government should be to publish the 2022 Student Income and Expenditure Survey and recommit to that Clarke principle – that maintenance loans should be set at such a level that students have enough money to meet their basic living costs while studying, paid for by cancelling the handout to the well off embodied by the removal of interest on student loans.

If the Treasury deems that too expensive, then we should ask if the current system, with its current participation rates, is really affordable at all.

Step two should be to recommit to that other Clarke principle – the maintenance loan no longer means tested, and made available in full to all full-time undergraduates – so that students will be treated as financially independent from the age of 18.

If the country can’t afford that, then maybe it can’t afford to expect those students to behave like adults either.

Then step three should correct, rather than extend, the original Clarke folly of bursaries from university budgets. Over time, the idea that students with additional financial barriers should ever be catered for from core university finances should be banished. It isn’t fair.

We can save the debate about whether vice chancellors make good landlords or heads of counselling services for another day. Today I’m arguing that the state should sort student financial support, not universities.

It’s the state, not other students at the university’s student debt, that should deliver what’s needed – and it’s the state that should adjust for students as parents, students in London or students who’ve experienced care.

Even in a world without tuition fees, redistributing around a university won’t come near to the redistribution that ought to be possible around the country.