A good timetable is like a well-crafted spider’s web.

Strong ties bring together a variety of the institution’s resources: curriculum, equipment, space and time. Intricate, beautiful, delicate, deliberately constructed, purposeful.

The one key difference? While it takes our average spider an hour to build its web, it can take six months of data collation, roll over, fixing, checking, and fixing again to get to a published timetable for August or September.

Historically, timetables have placed specific staff and students together in an appropriate physical space in which to teach, learn, interact and co-produce. Those timetables represented the formal portfolio of teaching and learning activity to each student in 2D.

However, the timetable is only as good as the data on which it is based. This year, there are changes to curricula, modes of delivery and room use. Even now, in early August, we don’t know exactly what things will look like in September. Gaping holes? Maybe not, but certainly there will be no comprehensive timetables, and what there will be, will only cover teaching up to January. Semester two, with all its uncertainty, has been kicked down the road in many institutions.

Promises, promises, promises

Universities are promising new and returning students the opportunity to attend face-to-face teaching (sometimes data-based, sometime not). Universities are desperate to convince students to come back to campus, to part with their tuition fees, to engage. They will have one or two hours of instruction time per module or perhaps three to five hours per programme. Don’t get us wrong, we like targets, but that’s all they are at the moment; aspirations that academics, space managers and timetablers are trying to make a reality.

Academics are busy redesigning curricula, redistributing teaching into different sized blocks, and learning new skills to prepare materials and maintain engagement. Space managers are still evaluating space protocols; timetablers are still collecting ever-changing data… Everything must be ready by the end of September to deliver against senior management’s promises, but everyone must also be ready to pivot online at short notice (to respond to potential local lockdowns as well as preparing for possible individual quarantine periods).

Building your wall

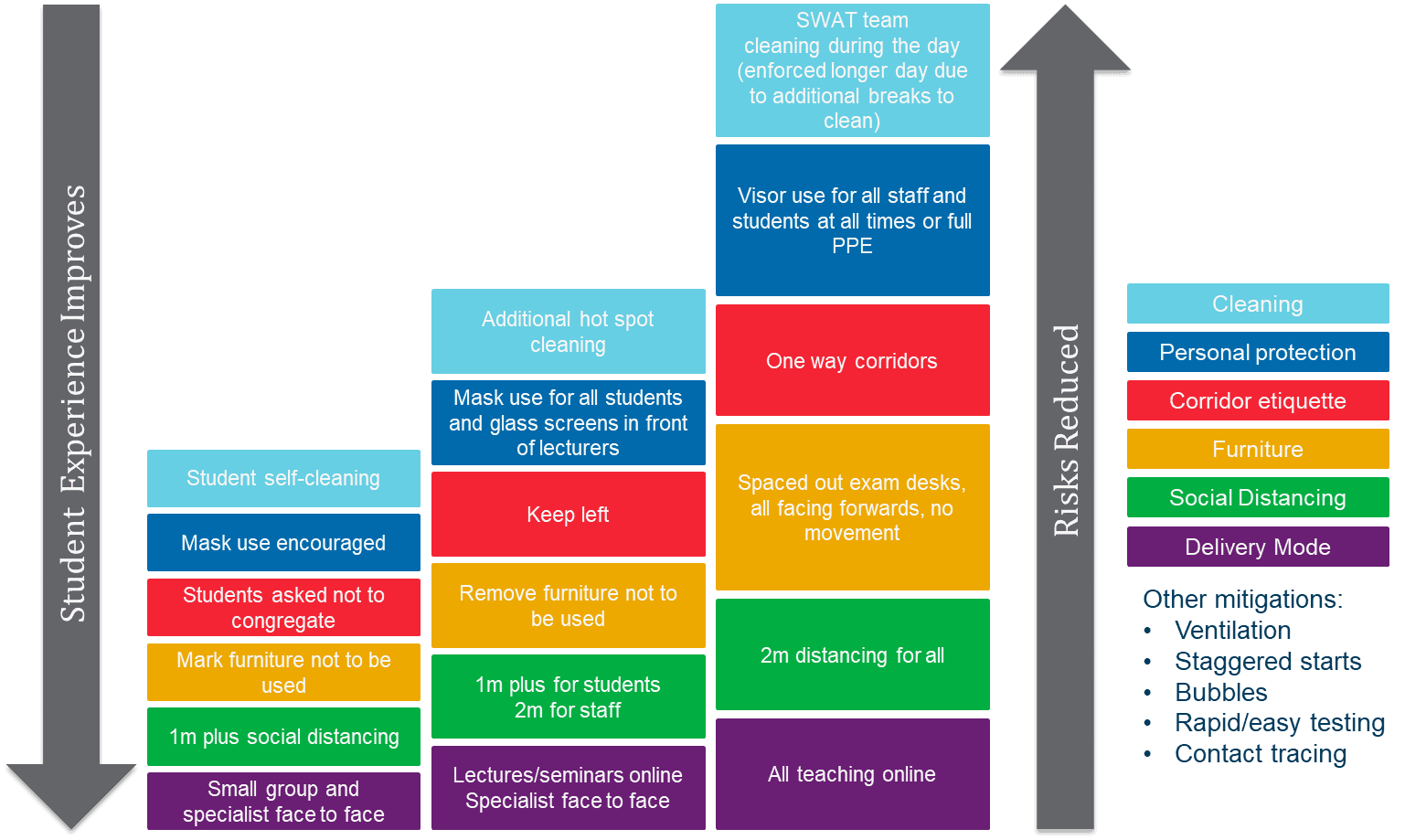

Here is where the wall comes in. Through our discussions with timetablers, space managers and colleagues across the sector, we have found various types of risk mitigation: personal protection, social distancing, changes to furniture, cleaning protocols and corridor etiquette, etc. For each level implemented, our wall gets higher and the overarching risk reduces. But as the risk reduces, we argue, the student experience suffers.

For example, one institution has put their lovely flexible wheeled tables and chairs into storage, set out their exam desks and chairs, and mandated that students face forward in class. How does this enable interactive activity? Can academics teaching from behind a plastic screen or face mask, restricted from moving through the class, maintain high levels of engagement? Queen Mary University is very sensibly trialling some of these protocols in a mock classroom to understand the impact of delivering small interactive sessions in large rooms on student experience, and looking at a range of ways to optimise engagement.

Expectation setting: do students understand the wall?

The mix of difficult decisions and subsequent chicken and egg operational activity is making communication with students difficult. We all know satisfaction is dependent on expectation: the marketing maxim of “under-promise, over-deliver” leads to the greatest satisfaction.

Communication is key. But what to communicate? There’s a tension between the need to say something – and say something positive – but at this moment, there’s not much that’s definite. Universities can talk about their approach including what is in their control and what is not, and what responsibilities students and staff will have to keep everyone safe.

So, when should students (and indeed staff) expect to get their semester one timetable? We are getting to a crunch point now in terms of the time taken to build, check, fix and publish. Six weeks is not enough in normal times, with the traditional academic summer absences, but in these strange Covid times it might have to be. Factor in significant disruption from clearing, and some institutions will struggle to finalise a timetable for the start of term.

Students and staff need to understand that timetables are provisional or are perhaps rolling; certainly not set in stone. All need to be patient and stockpile good humour to get through the first few weeks of inevitable upheaval.

Living with the wall: student engagement

Universities have been looking at ways to improve and influence student engagement in recent years. Most of this engagement has been designed with the physical space in mind; are students attending class, are they visiting the library? Now, we need to view engagement through an additional perspective (virtual) and for an additional purpose (contact tracing).

While in the past, universities monitored engagement to identify students at risk of not reaching their potential, now they have a duty to know who is where, who they have interacted with and how to contact them for contact tracing purposes. Imperial College London, for example, will use its own contact-tracing app to mitigate risk and catch outbreaks early.

The first thing universities need to know is how students intend to engage. Oxford Brookes will collect data from students indicating how they want to engage and will use this to place students in specific study groups (face-to-face or online). This can also be used to monitor how many students are self-isolating at any given point. Some universities are collecting time-zone information to assign international students to study-groups, reducing barriers to engagement.

Effectiveness: will students still achieve?

Any evaluation of the effectiveness of approach needs to be quick this year. Universities must be agile in terms of approaches to risk mitigation and the blend of delivery modes, and decision-makers must consider their respective and combined impact on student experience. Academics and professional services staff need to sit down with student representatives early in semester one to understand what has worked and what needs to improve. There’s no time for navel gazing, complex surveys and long reflections.

Staff need to turn feedback into concrete policy decisions by the end of October and make changes to plans for semester two in early November. Otherwise, our timetabling colleagues will struggle to produce schedules by the start of the second semester.

Timetablers can help by indicating which changes can be made in-semester without impacting timetables and which will have to wait for semester two. Academic networks will be important to spread the word, especially to those who only teach in the second half of the year.

Flexibility is everything

Timetables are built on known requirements, but our current situation demands flexibility. We’ll learn more over the next few weeks regarding home and international applicant intentions and the potential impacts of local lockdowns. We need to enable agility in timetabling by making principled decisions now, agreeing curricula and delivery modes, and moving forward with scheduling. And we need to keep evaluating our decisions through September and October, into the scheduling period for semester two, learning as we go. Let’s make sure our wall isn’t made out of concrete blocks; best go for Lego, foam or something equally agile as we build, destruct, pivot and build again.

Thanks for an important overview which overlaps with my thoughts on this to make sure that #Inclusion isn’t overlooked in this process and impacts are mitigated by EqIAs, dialogue and involvement.

See https://aua.ac.uk/edi-another-casualty-of-covid-19/