Barely a month goes by without another new report reminding us that there’s a mental health crisis in our universities.

The latest to hit inboxes comes from Accenture and Cybil (the new name for the market research arm of Group GTI) and in many ways the findings are upsettingly familiar.

When 12,000 students across 140 providers were asked late on in 2020, over a third said that they were currently facing a mental challenge. Four in ten said that their mental health had declined since starting university, and more than half had at least seven symptoms of poor mental health over the previous year.

Trans students, physically Disabled students, gay and lesbian students, and those from lower socioeconomic groups reported the highest levels of poor mental health. Women were more likely to report poor mental health than their male peers. And the findings suggest that a third of African Caribbean students were unable to describe their state of mind, which the report says suggests significant unidentified (and unmet) need and highlights the need for a culturally sensitive approach to mental health.

Those with longer term mental health issues were much more likely to have their mental health decline further at university (58 per cent), followed by neurodiverse students (49 per cent), those with disabilities (45 per cent), women (43 per cent) and LGBTQ students (42 per cent). Worryingly, one in four reported suicidal thoughts for the first time during university (25 per cent), which rose to almost half of those from lower socio-economic groups.

Who knows whether all those figures are worse than usual – I could look it up, but by now stats about student mental health are so familiarly negative as to leave most readers numb. There’s also more than a hint of the old “don’t blame us for what schools do” excuse that used to get deployed a lot around widening participation – as a swirl of hypotheses on everything from social media to “increased awareness” to austerity to the state of the NHS are used to explain away the crisis that presents on campus.

So in a year when “well it’s the pandemic” will provide cover to ignore or sideline all sorts of issues, the even more important questions than usual are “what’s causing the problem” and “to what extent is any of that in the control or under the influence of universities”. And while this isn’t a report that gives us definitive causation or perfect intervention ideas, it does at least offer helpful new clues as to what it is that’s inside a university that could help.

Playing on the mind

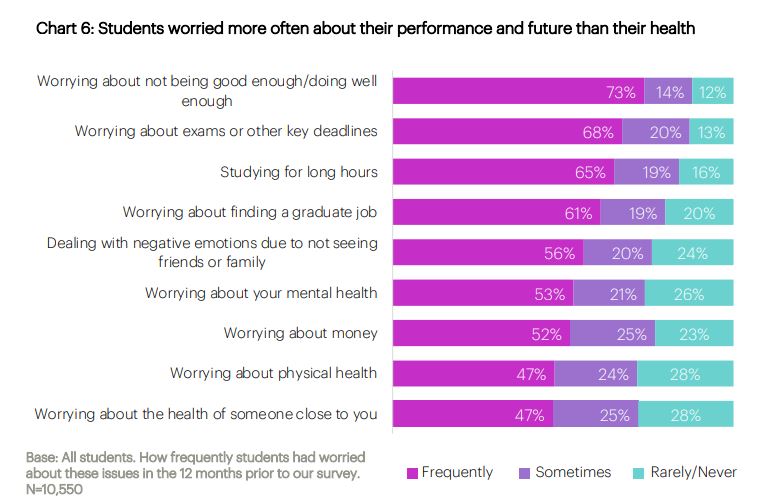

There’s an interesting stat early on in the report that I’ve not seen equivalents on before, that looks at what students were worrying about last winter. A whopping 73 per cent were worried about not doing well enough, 68 per cent were worried about exam and course deadlines, two thirds were worried about workload and studying for long hours, and almost half were worried about theirs or others’ health.

Maybe the lack of social interaction has robbed students of the ability to bounce their uncertainties off both academics and other students – but in any event, interventions that make expectations clearer and boost students’ confidence feel like priorities for the year ahead – especially when the survey also shows that a quarter of students felt “completely“ or “somewhat” unprepared for higher education, and those that felt less prepared were much more likely to report mental health challenges.

Loneliness was also a major factor. Reflecting results from previous work, of the five-plus lifestyle factors measured in the survey, loneliness was most strongly correlated with mental health outcomes. More than half (55 per cent) said they felt lonely every day or every week, and 45 per cent said they had been avoiding socialising in person or online with others.

We might look to Covid-19 and the resulting social distancing and lockdowns as the root cause of students’ loneliness, and obviously the pandemic will have the situation worse – but the figures are just 11 percentage points higher than those found in our 2019 Cibyl study, Only the Lonely, where 68% of students reported feeling lonely on at least a monthly basis.

Friendships matter in that – and so it’s worrying that even in UG years two and three, one in five students report that “they don’t have any real friends at university”. And out of those who have friends, over a third aren’t satisfied with the quality of their friendships. When asked whether they feel they have “someone to call on if they wanted company or to socialise”, a third either disagree or are unsure.

Those living with their parents and young carers were among those struggling the most to build friendships – which suggests that both universities and their SUs still have more to do to target opportunities to build social capital at those who would struggle to “commit” to more traditional forms of student involvement.

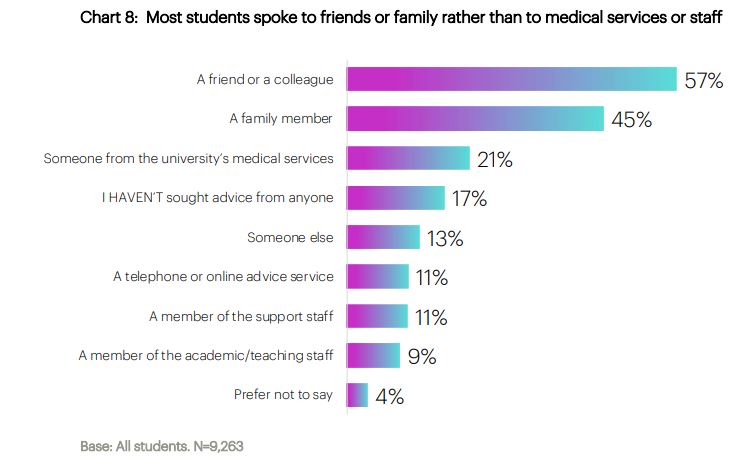

And it’s notable – if not especially surprising – that students turn to each other over their mental health. Even where types of students are more likely to form friendships, the extent to which we support students to support each other – particularly in difficult residential settings – has been the subject of previous research.

17 per cent of students speak to no-one about their mental health, most who experience mental health challenges do not access any services (that’s 60 per cent of those who have a current mental health challenge, who are unsure how to describe their mental health and/or who say their mental health has declined since starting university).

Offering support

There’s a whole heap of findings in the report on what is offered by universities on mental health – and interestingly, the most popular interventions were not perceived as the most effective. Mentor/buddy programmes offered and run by universities, for example, were used by only 14 per cent of students accessing services but were ranked as the most effective service by those users.

Mentors and buddies top the list when it comes to the effectiveness of service (80 per cent of users rate them as effective), outperforming more traditional (and more popular) services such as GPs (61 per cent effectiveness) and wellbeing support services (63 per cent effectiveness). Mental health advisers and stress management workshops were rated as second and third most effective services (both running at just over 70 per cent effectiveness).

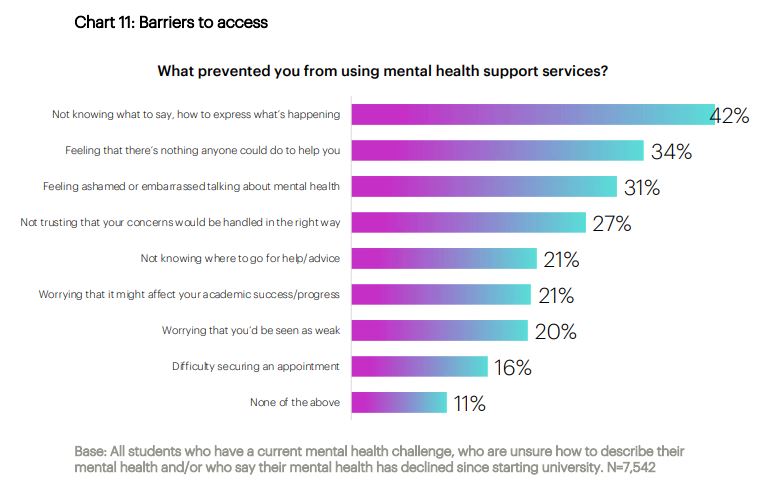

Just under half (with or without a mental health condition) said that their university was doing well when it to comes to supporting students with their mental health in general. But awareness seems to still be an issue – students who knew how to access help were nearly three times less likely to say their mental health had declined since starting there. And those same students were half as likely as others to be experiencing poor mental health at the time. Another chart on barriers also contains at some elements that look fixable:

Taking action

One of the refreshing things about the report is the recommendations – which feel manageable and actionable in comparison to the “whole provider approach” stuff we often get from UUK and Student Minds. That’s not to say that the “Step Change” framework or the University Mental Health Charter are not useful – but it is to say that I still frequently come across people at middling and senior level in universities that just don’t really know where to start on some of this stuff.

Recommendation #1 is understanding the mental health risk profile of students before they arrive, and taking steps to proactively target interventions. Using (both existing and proactively collected) data to understand whether students are entering university with existing challenges or are in vulnerable groups so that appropriate actions can be taken to support their wellbeing seems obvious at every level (including programme) – and makes sense if we see that UCAS intervention on condition declaration as a component of a wider strategy.

I’d add here that a risk assessment approach to student mental health probably ought also to include the sorts of things, events or issues that we know cause anxiety and unhelpful or undue pressure. I remain of the view that too few of the coronavirus risk assessments that I saw last summer covered mental as well as physical health risks – with inevitable results.

Another recommendation argues that universities should educate students in what good mental health is, how to maintain it, the value of seeking help early and how to support themselves and others – as well as educating staff to watch for early warning signs and have the confidence to “lean in”.

This is the sort of stuff that annoys some in this space who argue that it’s universities that should be creating less damaging environments – but there’s surely a way of reading this that would get us beyond “do an online induction module” and instead starts to properly explore where mental health could exist in the curriculum – which would better enable students to work in assertive partnership with universities to create healthier cultures and curricula.

In other words, yes (for example) assessment, workloads and timetables should not put undue pressure on students. But that’s a richer conversation if students and staff understand why and how poor assessment design or timetabling leads to pressure for particular groups of students, rather than that advocacy being heard as “special pleading”.

Another says that we should all help students make meaningful connections and relationships through building local communities and encouraging involvement in extracurricular activities – finding ways to make clear to all students that they should, and finding ways to reduce the commitment barriers of existing activities. And a final one says that universities should adopt the principles enshrined in the hippocratic oath – “do no harm” and “prevention is better than cure” – which seem as good a place as any for everyone with any agency and responsibility to start.

The statistic that 1-in-4 students has no friends at Uni seems unbelievable but I can see how it can happen. For many students their entire experience can live or die based on the great halls of residence lottery. Even if you have ‘colleagues’ on your course there is no guarantee they will become friends. Thus you have to rely on your flatmates for company and you may not even like them. I went halfway across the country for Uni and for a working class kid like me leaving your home town before 19 for anything other than a holiday was… Read more »