Devolution is a central plank of the government’s growth agenda. Providing places with the tools and resources to address local problems in ways that make sense on the ground is a means to unleash potential – and to end what English devolution minister Jim McMahon is happy to call the “top-down micromanaging” approach of ringfencing funds and centralising decision making.

The launch of the English devolution white paper is the first step on that journey. Strategic authorities, led (for preference) by elected mayors, will cover the entirety of England. Integrated settlements will provide powers covering transport, infrastructure, housing, public services – and, of particular interest to the higher education sector, skills and innovation.

A big part of the work of the white paper is in consolidating and standardising what had become an unruly system. Sitting above unitary, county, and district councils, a layer of strategic authorities will take on the services that larger areas need to thrive:

Our goal is simple. Universal coverage in England of Strategic Authorities – which should be a number of councils working together, covering areas that people recognise and work in. Many places already have Combined Authorities that serve this role.

The forthcoming English Devolution Bill will enshrine this concept in law. We get a computer game-like hierarchy of how strategic authorities will level up (so to speak): foundation strategic authorities (which do not – yet – have a mayor), followed by mayoral strategic authorities, which can then “unlock” designation as established mayoral strategic authorities through fulfilling various criteria. This will grant integrated funding settlements and other treats such as the ability to pilot new kinds of devolution.

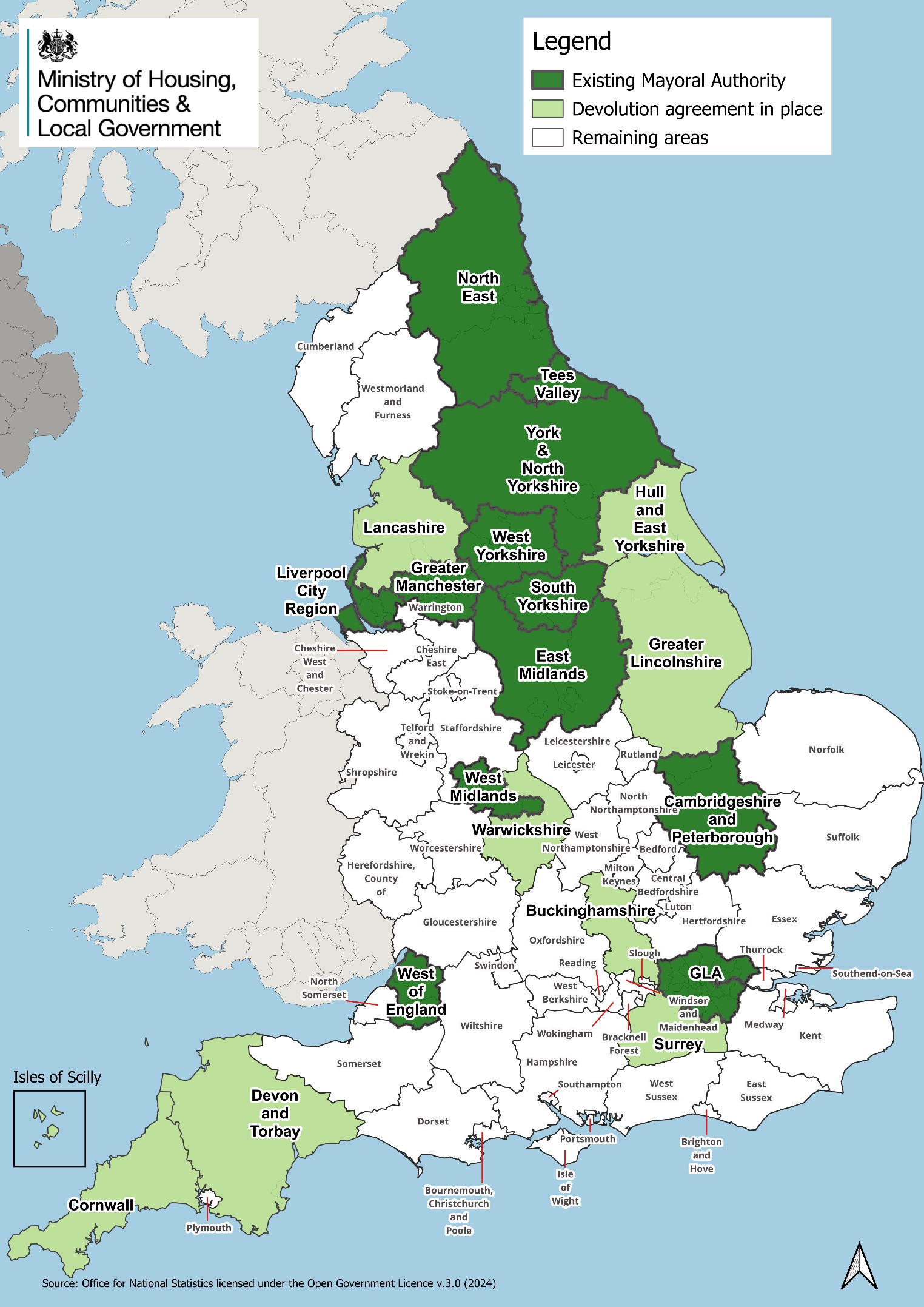

Already eligible for this top designation are Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, the North East, South Yorkshire, West Midlands, and West Yorkshire. There’s an aspiration for something similar to apply to London as well, but some legislative fiddling will be needed due to the capital’s “unique circumstances.”

Innovation

If you’ve got your head around the different levels of hierarchy, there’s actually quite a lot in the white paper for research and innovation, dependent on an area’s level of devolution.

In language echoing the industrial strategy green paper, we are told that a strong local network of public and private institutions focused on R&D, innovation, and the diffusion of ideas “is one of the factors which sets highly productive local economies apart.” A big part of this is closer join-up between UKRI and local government.

Working our way up the devolution ladder, all strategic authorities (including foundation level) will be able to draw on UKRI data on the location of R&D investments, to better allow them to “understand publicly supported innovation activity in their region and how to best take advantage of it.”

Those mayoral strategic authorities will additionally work with Innovate UK to produce joint plans, to shape long-term innovation strategies and investments in places. UKRI will also be extending its regional partnerships and “network of embedded points of contact” with mayoral strategic authorities.

And then coming up to the pinnacle of devolution, those established mayoral strategic authorities – to remind you: Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, the North East, South Yorkshire, West Midlands, and West Yorkshire, and possibly London – will get actual devolved research funding, in the form of a future regional innovation funding programme allowing local leaders to develop “bespoke innovation support offers for their regions.”

This draws somewhat on the spirit of the Regional Innovation Fund, though this was allocated to individual higher education institutions – what’s on offer here sounds like a pot of money controlled by mayors. Its format is also to be based on lessons learned from the Innovation Accelerator pilot, which was funding by levelling up money.

Plus, established mayoralties will get an annual meeting with the science minister, more regular engagement with senior staff at UKRI, and the chance to be consulted on the development of relevant DSIT and UKRI strategies.

All in all, it’s a decent start down the road of a more significantly devolved research landscape. Important to note, however, that the actual funding on offer to established mayors is contingent on next year’s spending review, and so we’re talking about 2026–27 onwards here. And we might also observe that the House of Commons science committee’s inquiry into regional R&D, announced last week, has clearly been set up with an eye to influencing how this all comes together.

At least to begin with, there will also be a not insignificant gap between what’s on offer to the most established sites of devolution – some funds to spend as desired, a seat at the strategy table – and what those “foundation” strategic authorities receive, which will be little more than a bit of regional R&D data. There’s potential for imbalance between regions here. Foundation-level authorities are described as a “stepping stone” to later acquiring a mayor, but it could be a long and drawn-out process.

Skills and more

On skills, strategic authorities will retain ownership of the Adult Skills Fund (with ringfencing removed from bootcamp and free course pots to allow for flexibility), take on joint ownership of Local Skills Improvement Plans alongside employer representative bodies, and work with employers to take on responsibility for promoting 16-19 pathways. In future, strategic authorities will have a “substantial role” in careers and employment support design outside of the existing Jobcentre Plus network, as the Get Britain Working white paper gestured towards.

You’ll have spotted that this does not immediately extend to higher education, except to the extent that universities and colleges already get involved with adult skills provision. However the centre of gravity is such that any provider with an avowed interest in the local area will end up developing close relationships with strategic authorities. It isn’t just on skills or innovation – many universities work with local government on issues that affect students (and staff!) such as housing, infrastructure, and transport, and will have a strong interest in working with strategic authorities with new and wider powers to act.

Administrative geography corner

If you are labouring under the impression that dividing England up into administrative chunks is a fairly straightforward task, may we introduce you to possibly the single finest document ever published by the Office for National Statistics: the Hierarchical Representation of UK Geographies.

Pedants may also note that the existing geography of LSIPs, which was controversially allowed to evolve into being outside of the established local authority boundaries, does not map cleanly to current or proposed local authorities – something that a future iteration of plans may need to consider. Likewise, the scope of university core recruitment areas or civic aspirations may not map to either.

What we’d have loved to have shown you is a map showing which of the new strategic authorities your campus might be in. Sadly the boundaries of the “current map of English devolution” included in the white paper do not cleanly map to England’s many contradictory systems of administrative geography. Some of the devolved areas depicted are almost LSIP regions, one (Surrey) is a non-metropolitan ceremonial county, and one – Devon, including Torbay but not under any circumstances Plymouth – is just plain mad.

As soon as we get an answer and some boundaries from ONS, we’ll let you know. In the meantime, here’s the map from the white paper:

Thanx very much for this very informative post. As a former resident of the federations of Australia and Canada I have found this topic very confusing. I shall describe Australian arrangements, but Canadian arrangements are very similar tho with much more devolution to sub national governments – provinces and territories. In Australia all of the country is uniquely allocated to a state or territory, which are like the UK’s 4 countries, but with England divided into several subnational governments. All states and territories divide all of their region into local government areas (Canada and the USA have 2 levels of… Read more »

Really helpful summary, leaving aside the mapping challenges (and we all love a good ONS document), defining place and placemaking will be key here.