Given that it’s 50 years since they won Eurovision for Sweden, there’s been lots of focus both home and abroad on Abba.

There’s a cracking clip in the interval on Semi Final 2, for example, on how the win changed Brighton as a place. I won’t spoilt it for you.

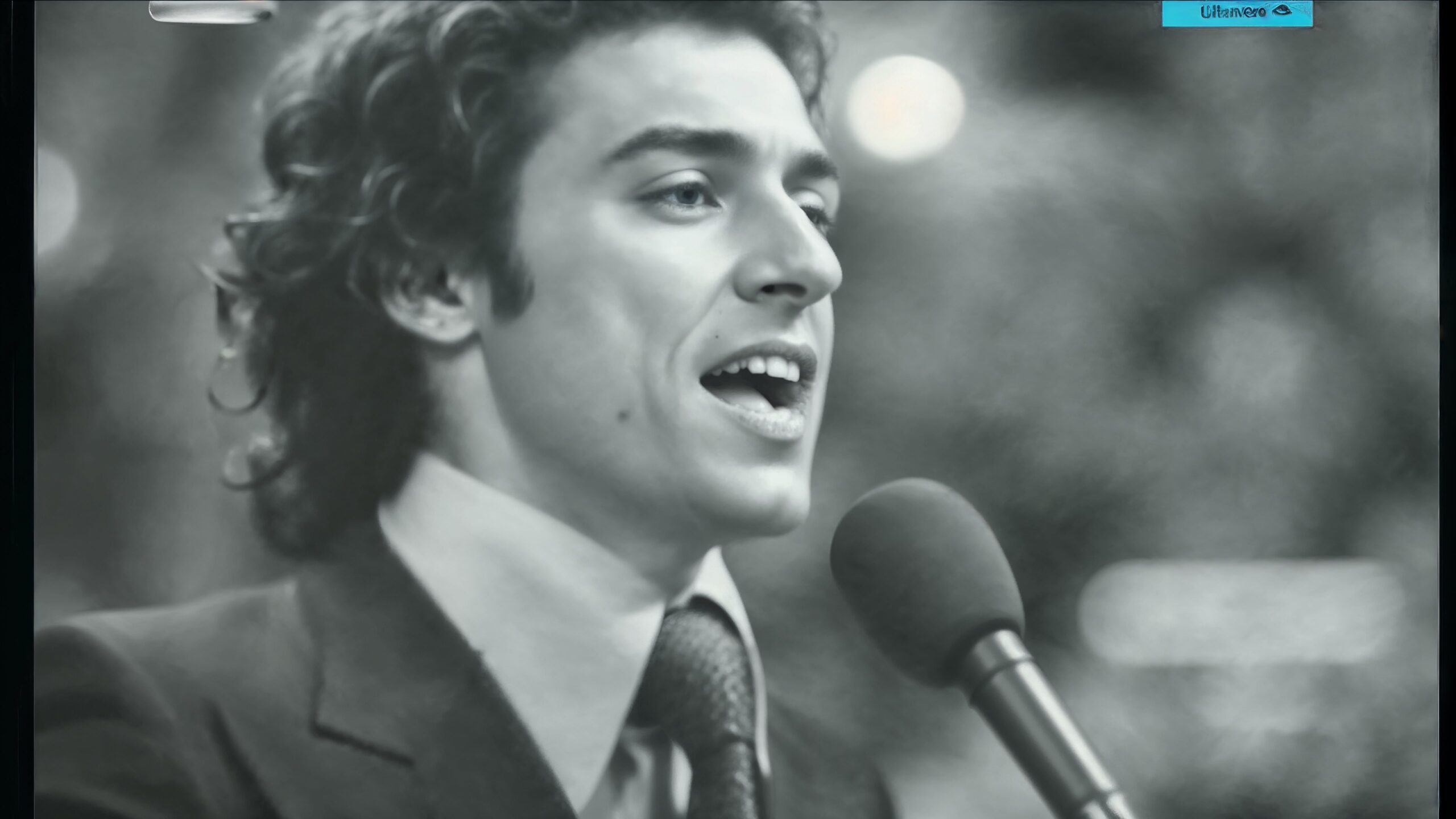

But for me the more interesting tale of Eurovision 1974 is that of the Portuguese entry “E Depois do Adeus” by Paulo de Carvalho.

To viewers at home, it was probably just another bit of bland Fado music – but at home it was part of a covert plan to trigger the overthrow of Portugal’s dictatorship.

By 1974, the Portuguese military was at a breaking point after 13 years of colonial wars in Africa, straining the Estado Novo regime’s resources.

Growing discontent among junior officers led to the formation of the Movement of Captains, a sophisticated and organised group pushing for an end to the war and a democratic transition.

Pre-internet, the plan involved using civilian radio broadcasts to signal the start of the Carnation Revolution – executed by “E Depois do Adeus” at specific times across different radio stations.

And when it happened, the broadcasts successfully coordinated a military operation that led to the swift overthrow of Europe’s oldest fascist regime, marking the start of Portugal’s transition to democracy.

Value debates

It’s exactly the sort of tale that delegates to this year’s academic conference on the contest were able to immerse in at Malmö University, whose theme this year was the complex relationships between music, identity, and migration.

There was a Science Slam for early career researchers, round table discussions featuring an interdisciplinary range of academics and “enthusiasts” from Germany, Portugal, the UK, the Netherlands, the USA, and Sweden, and a special documentary screening on the Portuguese Festival da Canção in partnership with its public broadcaster RTP.

One of the papers being presented was from Ben Robertson, a former SU sabbatical officer (and Eurovision Soc President) from Durham University, whose research explores the influence of the running order on the results of the contest.

By analysing juror rankings from 2014 to 2022, he’s found a significant correlation that suggests that performances later in the lineup tend to score better – something that’s all the more controversial in an era where producers have more control over the running order than ever.

For me there’s considerable academic value in studying presence or absence over the years of certain countries, the winning acts, the hosts’ commentary, and the news coverage that surrounds it all – the Prague Spring, street riots in Belfast, that Carnation Revolution in Portugal, the end of the Franco dictatorship, the Cyprus conflict, the eastward expansion of the European Union, the Orange Revolution, and the war of aggression in Ukraine all find echoes in the contest.

As Croatia sail to what I’m sure will be a landslide victory on Saturday, do if you can find the time to disappear down Catherine Baker’s superb look at the country’s Eurovision journey from near-champions to underdogs and back to favourites – a story full of cultural and political shifts – with Rim tim tagi dim already emerging as a symbol of national pride and cultural identity.

Dog biology

Of course critics might argue that books like Catherine’s forthcoming Handbook of Popular Music and Politics of the Balkans is a good example of the sort of thing that shouldn’t attract taxpayer subsidy.

Mats Persson, Sweden’s Minister of Education is on the warpath over HE expansion in the country – arguing that previous social democratic governments have used higher education as a way to hide youth unemployment – and that there’s been too much focus on quantity over quality:

The Social Democrats have long held a dogmatic view that the important thing is that as many people as possible attend an education that has an academic stamp. This has resulted in the fact that today you can study courses in beer knowledge, wine knowledge or dog behavioural biology at Swedish universities. Many people ask themselves whether it is really reasonable for taxpayers to fund courses that could just as well be given by other institutions than universities. Is it reasonable to prioritise what are perceived as hobby-like courses in the university in a situation when healthcare and industry are crying out for competence?

The big plan is to reduce the “flora” of funded places on independent and distance courses, tackle the “academicising” of more and more professions, and restore the value of an academic education.

And naturally, it has provoked the sort of response we often see over Mickey Mouse degrees or Golf Course Management masters’ in the UK:

Knowledge of wine stands securely on a scientific basis in the subject of oenology, which is a subject established in research and higher education globally. It is a topic that, in a Swedish context, has a clear connection to the hospitality industry. It is an industry that, if it escaped Mats Persson, is also crying out for competence. The restaurant industry is also an industry that historically and through its historical heritage is characterised by high staff turnover. It is also an industry that offers many, especially young people, an entry into the labour market.

In an industry such as the restaurant industry, where employees are constantly replaced, it becomes important to have a stable and knowledgeable base that can be responsible for the new employees and that can contribute to both their and the industry’s development. It is precisely for this stable and knowledgeable base, in one of Sweden’s largest industries, that courses like wine knowledge become important.

Fredrik Kopsch, chief economist at the liberal market think tank Timbro, argues that fee-free education leads to students taking longer to enter the labour market; that when students are required to pay for their education, they tend to take their studies more seriously; that when students financially contribute to their education, they demand higher standards; that fees would lead universities to offer courses that are in demand by the market rather than courses influenced by political decisions; and that students would take into account to a much greater extent which courses lead to better jobs and higher salaries.

The Eurovision heart of the system

Reading Kopsch’s blogpost on the website of Southern Sweden’s leading morning newspaper is a surreal experience, given the way in which it reflects both our own right-wing press’ attitudes to HE and the ideology in 2010’s Students at the Heart of the System.

Part of me wants to jump on a train to Stockholm, pitch up at the Riksdag and present to Mats Persson on all the reasons why the arguments are flawed, but they’d probably arrest me – and anyway I need to back in Malmö tomorrow for a separate day of seminars, lectures and cultural activities related to the contest from an EU perspective.

There’s going to be discussions with academics, students, diplomats, and other guests as they share their perspectives on Europe, and highlight EU values linked to the contest’s history – including human rights, media freedom, and cultural diversity.

They’re hot topics in a year where Israel’s participation (and significant opposition to it) is stretching the broadcasting union’s ability to hold together a contest that proclaims that it’s about the values of universality and inclusivity – with security dialled up so high that it took over two hours to get over the Øresund bridge last night because protestors were blocking it.

At Friday’s event, I’m not even paying for lunch. Mats Persson will be furious.

All this Rim Tim Tagi Dim is making me Dizzy, Jim.