In a week that has already seen politicians from all three major parties suggest a rethink on higher education finance, a major IFS report (‘Higher Education Funding in England: Past, Present and Options for the Future’) is a timely and provocative intervention in the growing public debate. Similar research from IFS underpinned their 11th May response to Labour’s election campaign pledge to abolish fees and restore grants. In the maelstrom of the election campaign, some of the nuances of this analysis were lost – today’s release allows us to take a more nuanced view.

What this report does well is to foreground one of the axes of policy making – the difference between a long-term and short-term focus. Our current tuition fee model is very much focused on the short-term benefits: more money to institutions, lower government borrowing. The IFS describes these alongside the likely longer term costs. These include the direct financial cost of un-repaid loans that must be written off by a future government. But it also includes indirect opportunity losses, such as the ability to prioritise particular subject groups or the effects on higher loan repayments as a percentage of graduate salaries as a supplementary income tax.

The other axis of policymaking concerns the difference between the political optics of a statement like “only graduates earning over a threshold will repay loans”, and the lived reality of high levels of debt – from both fee and maintenance loans – at the start of a career. Again IFS draw out some of these tensions in their analysis of a model of repayments over the next 30 years.

Key findings

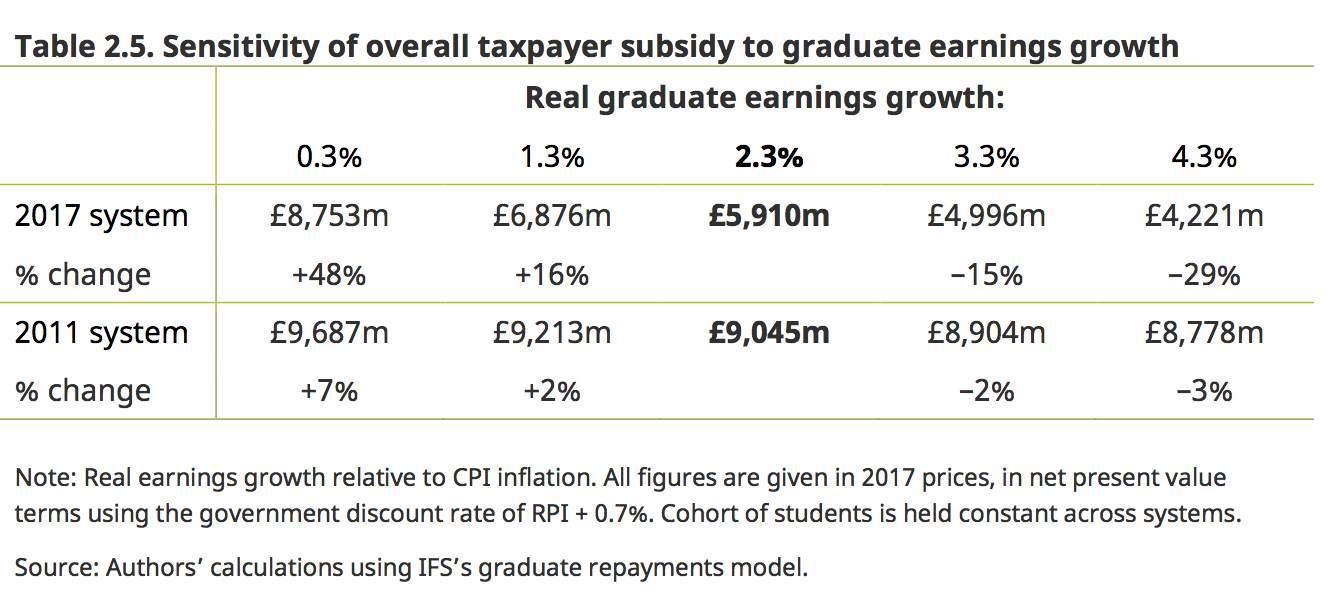

The current system of fee and maintenance loans has decreased both short term and long term direct government funding for higher education while increasing institutional funding, but the long-term benefit is linked to the performance of the graduate job market and the wider economy. A 2% decrease in expected graduate earnings increases the long run government contribution by 50%!

Source: IFS

English higher education now sees students from the poorest 40% of families graduate with the highest debts: £57,000. These are repayable at 6.1% (RPI+3%) in cash terms from September 2017, meaning that an additional £5,800-£6,500 will be accrued by all students during study and up to £40,000 in interest is repayable by high graduate earners during the lifetime of the loan. The current system of maintenance loans – which replaced maintenance grants in 2015 – is reported as the primary cause of this overall regressive change to the distribution of debt by parental income, even though the fee loan system itself could be considered progressive.

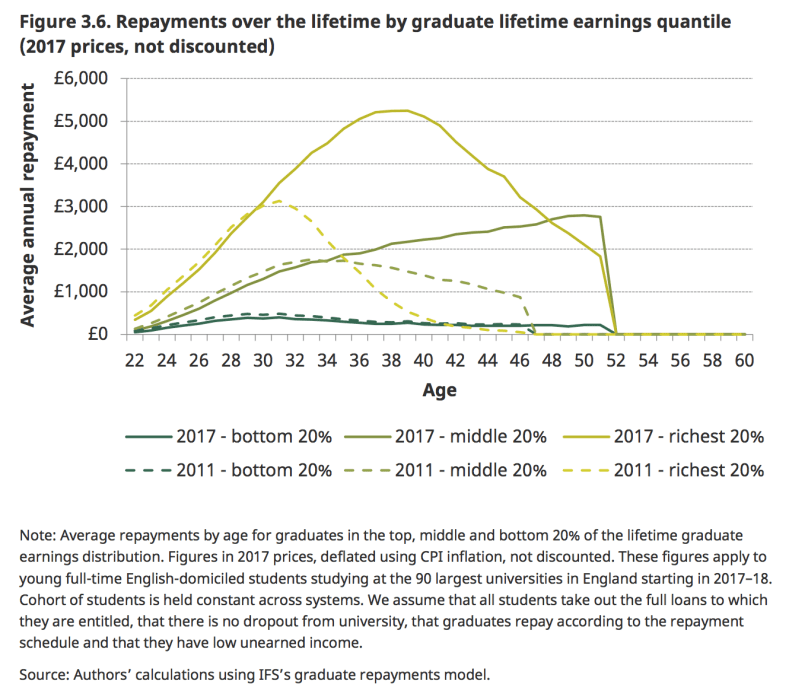

The IFS show that the impact of the repayment threshold freeze is concentrated in the middle of the earnings distribution. Low earners still see the majority of their earnings below this threshold, and higher earners will have repaid their entire loan anyway( though in the latter case repayments will be skewed towards the early part of a graduate career). Continuing the threshold freeze for a further five years is calculated to save the government £700m.

77.4% of all graduates will see some debt written off after thirty years; this includes a “non-negligible” part of the richest 20% of graduates (Table 3.2). The impact of the 2012 reforms on the lowest 20% of graduate earners have been negligible – this group will still fail to repay their loans but will continue to make repayments for a further five years.

Source: IFS

Higher education providers have done very well out of this system, with substantial increases in the level of funding available in all subjects. The report notes that the increase in available funding since 2011 is particularly striking in the old HEFCE group D courses such as the humanities, and most social sciences. (+47%). This offers an incentive for institutions to recruit heavily to cheaper to run these courses – valuable courses in their own right, of course – but an incentive that runs at odds with a wider focus on STEM subjects or indeed general labour market demand.

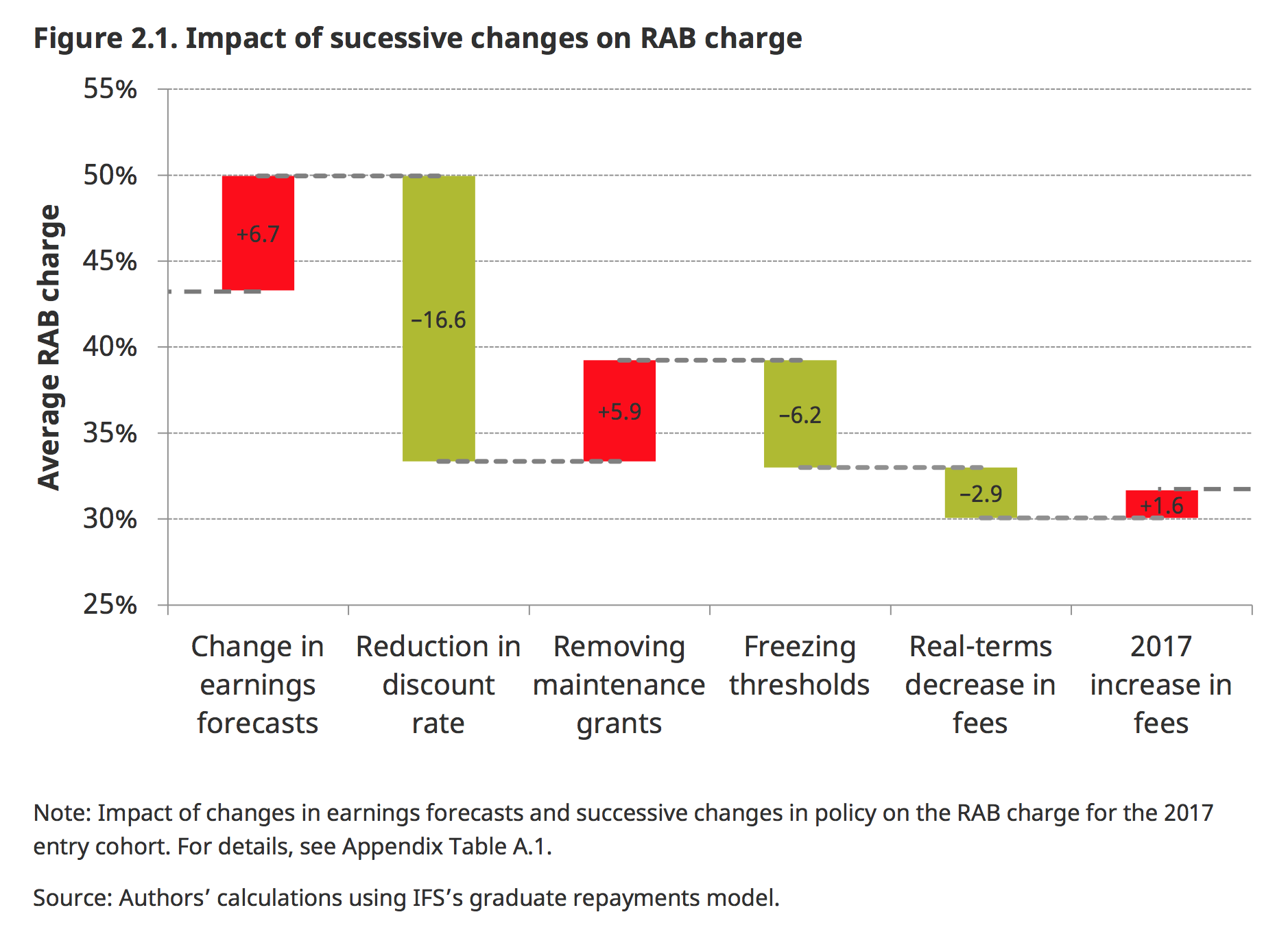

The report is also one of the first to deal with the effects on government finances from the way the RAB charge is calculated. Figure 2.1 offers a useful visualisation of the way RAB has fluctuated with policy and accounting decisions alongside changes in the wider economic environment. The current estimated RAB charge (31.3%) has dropped from the 2012 estimate (43.3%) via a combination of a reduction in the discount rate, a drop in real terms in the value of fees, and the freezing of the repayment threshold. The external pressure on RAB (via changing earnings forecasts) has been upwards – with the replacement of maintenance grants with loans also moving RAB up.

Source: IFS

The politics of fee policy

IFS consider the impact of the Labour manifesto proposal to abolish fees and restore grants, alongside other potential future changes to funding:

would have the advantage of allowing government to target specific students or courses that have wider benefits to society. This would, however, significantly increase deficit spending and lead to a smaller, but still considerable, increase in the long-run government contribution. In future years, the government should put more weight on the latter than the former in its approach to making policy.

But there are plenty of concerns raised with possible adaptations to the current system. In considering the effects of an as-yet-unplanned change of the repayment rate, IFS notes one of the wider implications of the fee level is that it becomes – effectively – an additional tax on earnings for graduates. The reports write that: “It is, therefore, possible that a higher repayment rate could reduce the incentive to work or earn more. This could reduce the level of graduate repayments and, more importantly, the receipts from income tax and National Insurance contributions.

On the current system, the major IFS concerns are:

- Although we have yet to see large declines in student numbers, the long-run cost of university is now considerably greater – both in terms of debt on graduation and in terms of long-run repayments – for prospective students, and this may reduce participation in the longer term.

- The current system does not give the government much flexibility to directly target courses or individuals that have high value to society. This is because the vast majority of the government contribution to HE teaching now comes through loans that are not repaid by low-earning individuals.

Conclusion

Funded by the ESRC Centre for the Microeconomic Analysis of Public Policy, the report details two decades of “near-constant reform”. Those hoping for stability and certainty may be disappointed in the years to come.

Concerns about loans, access and affordability, have a long history in UK HE. One backbencher in the debate on Dearing nearly 20 years ago presciently remarked:

There is real concern that the Government’s decision not to follow Dearing’s proposal to introduce tuition fees while maintaining the maintenance grant, but rather to abolish the maintenance grant and replace it with loans will, far from widening access, narrow it.

Theresa May – for yes, it was she – hit the nail on the head. Discussions about affordability and access have to take place while looking at the entire student support and HE funding package. Taking a report (as happened with both Dearing and Browne) and cherry-picking politically or economically attractive aspects is not a recipe for a fair or sustainable system.

We will see further reform of the system in the years to come – the appetite is there, and the issues with the current system are becoming apparent. Funding HE – fundamentally – is a political decision, not an economic one. Reports like this one make clear the effects of any possible decision, but it is up to politicians to make the choice.

What about the “threshold effect”? I know quite a few people from my generation who have carefully always earned just less than the repayment threshold in order to put off paying off their loans… since the 90s. Not only does this effect repayment rates, it also affects the tax take generally.

Hi Scott – I’d agree it would be interesting to think about that, but I suspect it would be very difficult for even IFS to measure the extent.

I think the threshold effect doesn’t really apply now, because of the shift from the original ‘mortgage-style’ student loans to the income-contingent form we have had since 1998. With mortgage-style loans you defer repayments if you earn under a certain threshold, set at 85% of the national average wage. Over that threshold you pay the same amount regardless of earnings, and the repayments are structured so you repay in 60 monthly instalments (84 if you have five or more loans). Therefore the ‘cliff edge’ between paying and not is much starker than for the income-contingent system that applies to the… Read more »

Even in countries like Australia, where you repay on all your income after going over the repayment threshold – which as a result means effectively a $1 increase in wage can lead to over $2000 liability for HECS loan repayment – despite the marginal tax rate being huge and the incentive to rational incentive to remain below the threshold high, they haven’t seen a major distortion of the graduate labour market.