The attention necessarily paid to undergraduate study can elbow out discussion of postgraduate study.

After all, if we can’t agree on how to admit, grade and fund people attending university for the first time, it’s not surprising that we struggle to have proper conversations about the people doing all of this again.

Which explains why I was genuinely excited to see Wonkhe using the current “calm” in UK policy announcements to ask if we really understand what’s been going on with PGT.

My interest is partly because this sort of thing is my job at FindAUniversity (tl;dr: helping PG students understand university; helping universities understand PG students).

But I was especially enthusiastic (so much so I took to Twitter on the school run) because I think DK’s piece gets right to the heart of one of the key issues with PGT conversations: understanding this part of the sector through an undergraduate framework risks fundamentally misunderstanding it.

I want to highlight some other unique challenges with PGT fees, funding and participation.

Postgraduate students aren’t undergraduate students

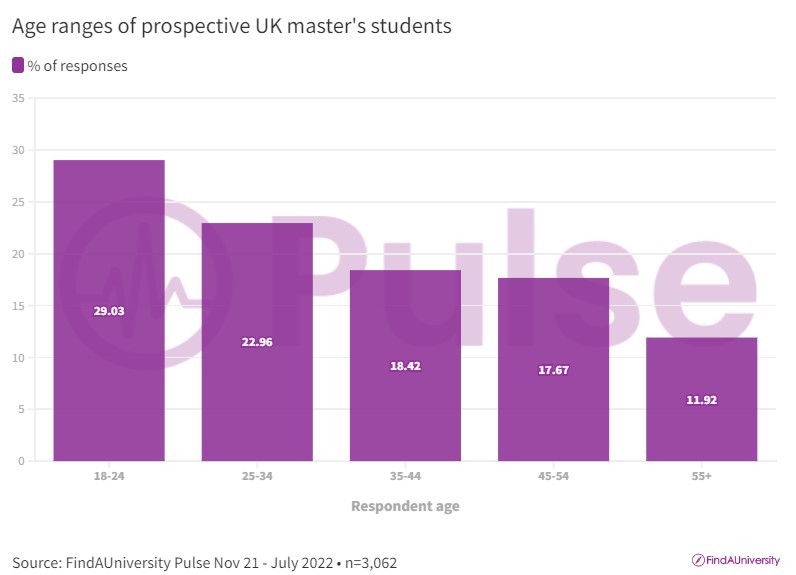

And nor are the majority of prospective postgraduates. Here’s the age profile for our UK FindAMasters audience (via our opt-in tracker survey) since last November:

Yes, 18-24 (fresh grads – and, no, none will actually be 18) is the biggest segment, but 25-34 year olds aren’t far behind; and, if we take 25-44 as a core working age group then that’s the majority.

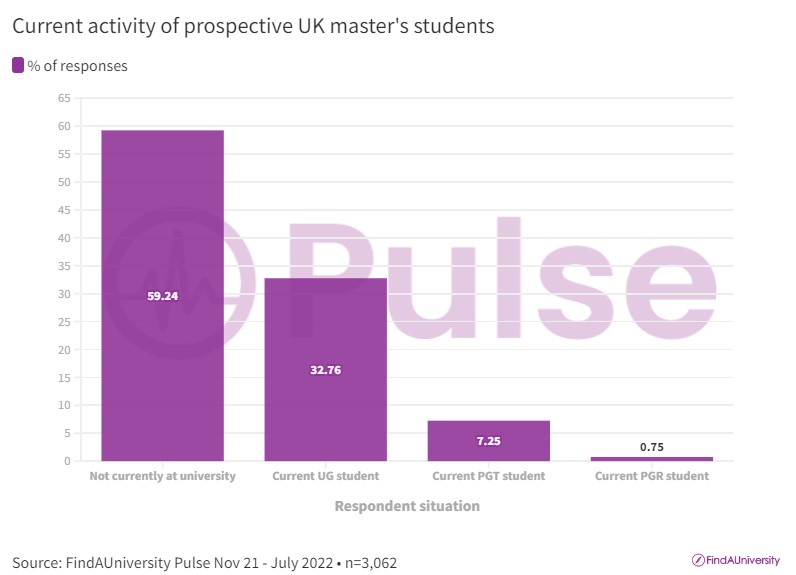

It’s similar if we look at what the same group of people are currently doing:

Almost two-thirds of the people looking for a master’s aren’t currently at university.

I hope this double-underlines DK’s point that the UG framework just won’t fit: we can’t think about continuation and outcomes for programmes that mostly recruit working professionals in the same way as those who mostly recruit sixth-formers.

But does it work?

2020-21 was a bumper year for PGT recruitment and there’s a good chance the pandemic also made PGT more varied.

So, if more people (and more types of people) are studying PGT, does it need fixing? It does, because the economics of postgraduate participation are becoming increasingly problematic.

Put simply, PGT fees and funding are broken. We don’t know enough about the former, the latter isn’t sufficient and, in any case, they bear no logical relationship to each other.

Studying between shrinking margins

Universities set their own PGT fees and DK is right that there’s no comprehensive (and freely available) reference for these. At least, I’m not aware of one, and I edit a website that tries to tell people what the average cost of a master’s is.

The best we have are annual surveys now mostly available as paid data products. This means that nobody – including the OfS – has a way of properly understanding what’s been happening since the postgraduate loan was introduced in 16/17 (despite the government promises to monitor fees afterwards).

Well, here’s my best napkin maths:

In 2015 (the year before the PGL launch) Times Higher Education had the average domestic PGT fee at £5,901, having risen by 3.9% from the previous year’s £5,680. In 2016 (the year the loan was introduced) it rose nearly 10% to £6,486. In 2021 the average was £9,500 – an increase of 61% on the pre-loan amount and more expensive than an undergraduate degree.

Fun(ding)’s over

Look at this another way. The £10,000 available via a freshly minted PG loan in 2016-17 would cover average PGT fees and leave £4,099 to live on. Hardly a lot, but a meaningful contribution. The £11,836 available in 2021-22 barely touches the sides.

We’re heading back to a pre-loan situation in which you can afford to do a master’s if you’re a working professional with savings, or a graduate with access to the bank of mum and dad. And, as I’m far from the first to point out, that’s a tragedy for widening participation at postgraduate level.

It’s no good just shouting at universities about this, either. It’s not their fault the PGT fee is one of the few student resource levers left to pull.

But this problem still really matters because – hold on to your hats – postgraduate taught study is lifelong learning. It’s also, increasingly, where access to professions like law, teaching and medicine happens – or where we do training in cutting edge fields like AI (PG subjects the government likes so much it funds them separately).

Widening which participation, where?

There’s another problem with PGT WP. We don’t talk enough about who wants to do a master’s and why. We know a bit about the people who do one, thanks to great work like PTES, but this is a rear-view mirror partially fogged by survivorship bias.

Of course we need to talk about the motivations and backgrounds of the people who go on (or back) to do a master’s and of course we should regulate in a way that’s sensitive to this (rather than simply transplanting a UG framework).

What about the people who want to do a master’s, though? Are they the same as those who do? What if they aren’t? This matters even if PGT study isn’t becoming increasingly unaffordable. And it is.

Starting points for solutions

The best thing we can do is carry on the conversation started by DK’s piece (and to which mine hopes to contribute).

Personally, I think we need to talk about:

Fees

What are they, for what courses, and what’s happening to them? We need to understand this as a sector and so do students – or else they’re navigating a market where none of the prices mean anything. We’re really keen to work with universities to get more of this information onto resources like FindAMasters and I guarantee we’ll make the data as useful and available as possible.

Access

We need to know who wants to do a master’s and whether they can. Again, this is something we’re working on at FindAUniversity (including the data above) but we’d love to work with others.

Funding

This is one we can’t fix, but we need to talk about options – as I tried to on Twitter. Do we peg the loan to fees (a blank cheque that won’t stop inflation)? Do we increase but restrict courses (horrid questions about access)? Do we move to a UG model (or does that just restate old problems)? Or do we think outside the box, look at places like Wales and maybe, just maybe, ask why PGT isn’t covered by the LLE plans?

Great article Mark.

I work for a company called S Squared Insights and we do offer a comprehensive record of every PGT fee.

It would be great to discuss how we can work together and help you understand the fees market.

I will follow up directly.