When you monitor both domestic and international coverage of international student issues as closely as we do at Wonkhe, you know when a story is having an impact.

Rishi Sunak’s marching of the sector up the hill of the graduate route being scrapped, only to march it back down with a package of other “tough” measures has certainly caught the eye of the media throughout India, Pakistan and Nigeria.

The climbdown is generally being reported as good news – although the signalling on English language requirements, the need for more money to get into the country, and the “smashing” of the business models of “some” agents isn’t exactly dousing the flames, even if they’re the right thing(s) to do.

But as well as the national shenanigans, a local story has worked its way around the globe too over the past week.

Poverty

Last Tuesday, BBC News North East and Cumbria reported that a group of students from Nigeria had been “thrown off” their courses and ordered to leave the UK, following the widely understood currency crisis at home left them unable to pay their fees on time.

Some told reporters they felt “suicidal” as they accused the university of taking a “heartless” approach to those who fell into arrears as a consequence.

The Guardian says that one student was forced to sell his house in Nigeria to try to meet his debts – while others, having been removed from their courses, were notified by UKVI that they had 60 days to leave the country.

It’s a bleak, miserable story – and one that has been happening in multiple universities around the country, too. The Guardian reports that around the UK, many Nigerians are sharing pictures and videos online showing them reducing portion sizes and eating food that would “normally be fed to livestock” in order to get by.

The difference this time is that BBC Regional News picked up the institutional story off the back of some local activism – and so it’s also now been picked up by lots of outlets around the world.

Pop in the right search terms, and you’ll see that it’s also all over TikTok, Youtube, Reddit and the WhatsApp groups that prospective international students use to get information about studying in the UK.

It’s also now apparently a diplomatic issue. The Guardian reports that delegates from the Nigerian high commission are to meet senior managers at the university to discuss the treatment of the group.

There’s a level of complexity to the story that BBC report almost, but doesn’t quite get at – one that concerns the relationship between the university and UKVI, the rules that universities are held to when sponsoring, and the way in which students are bound to blame their provider when something goes wrong.

Who said what, when, why and how is contested – but there are a couple of things that I thought were particularly interesting about the story.

Low value currency

Generally, I can make an argument that both the state and universities should have proper plans in place to cushion currency shocks when they occur. The broad message – well if you could afford it then, but following a currency crisis, you can’t now, so get out – stinks.

As BBC News reminds us, Nigeria is currently experiencing its worst economic crisis in a generation, which is having a significant impact on Nigerian students at some UK universities:

The annual inflation rate is now almost 34 per cent, partly driven by President Bola Tinubu’s dropping of a fuel subsidy last year that put up petrol and diesel prices and which has filtered through into the cost of other goods.

The government has also stopped trying to support the value of the naira on the currency market and it has depreciated in the past 12 months by more than 200% against the dollar.

That there is often confusion over whether universities are allowed to cushion for that is pretty miserable – although I suspect that doing so would be a dent in budgets that many providers wouldn’t wouldn’t find feasible anyway.

On the other hand, a sector lobbying HMG over the impact of inflation on home students’ situation should probably take a step back and imagine what 34 per cent CPI would be like.

I tend to take the view that if we must finance UK higher education on the backs of families from the Global South, the absolute bare minimum we should do is not deport them as soon as their currency collapses.

But to be clear – it’s not as if not doing so is Teesside’s fault.

How expensive is the UK?

What is arguably more problematic is that Teesside’s cost of living information for prospective students does what many, many other universities do – it points at UKVI’s maintenance minimum as a “guideline”:

It is important to think about not only your tuition and accommodation costs but the cost of living too. The minimum cost of living as recommended by UKVI for studying outside London is £1,023 per month, but will vary from student to student. This is a guideline to cover items like accommodation, food, laundry, books, clothes, toiletries and socialising.

It may well be that Middlesborough is cheaper than the average town, although Teesside does have a London campus too. Either way, as I’ve said on here before, it’s a deeply faulty price signal – it’s a number that hasn’t been raised in over five years, and is some considerable distance from HEPI’s mooted “minimum income for students” figure from last week.

Of course even if the cost of living information was better, that wouldn’t have fixed the currency devaluation issue.

Respect the contract

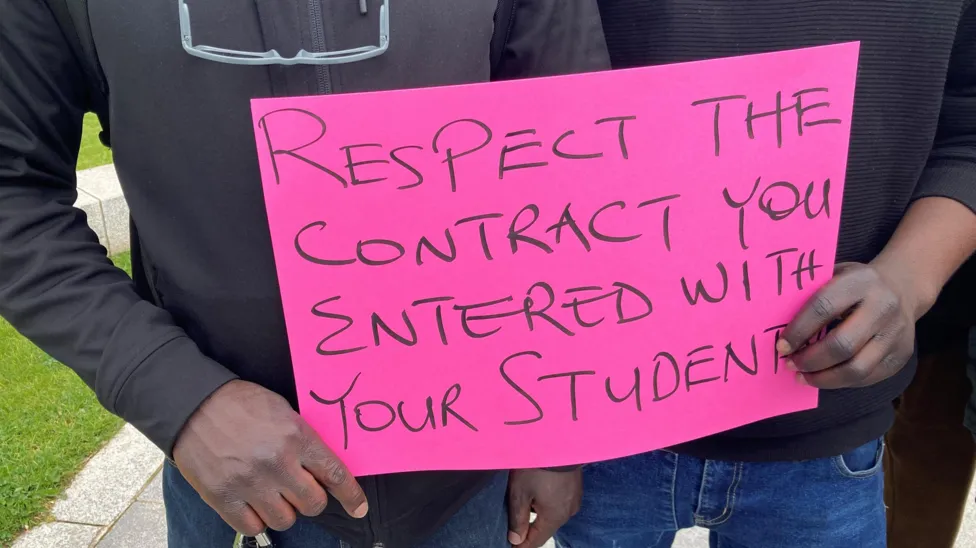

But what also caught my eye was this photo in the story:

Having listened carefully to some local activist YouTube coverage of the story and cross-referenced with the BBC coverage, it seems that students are alleging that they were offered the opportunity to pay in seven instalments – but that upon enrolment, that was switched to three:

Before beginning their studies at Teesside, affected students were told they had to show proof of having enough funds to pay tuition fees and living expenses.

However, those funds were significantly depleted as a result of the crisis in their home country. This exacerbated financial problems already being experienced by students as a result of the university changing tuition fee payment plans from seven instalments to three.

That is fascinating – because pretty much all year, international student sabbatical officers in SUs have been asking us for information on which universities offer multiple instalments with a view to increasing them, rather than decreasing them.

It’s not clear whether the students involved here are alleging an actual breach of contract, or whether when they enrolled that what the Competition and Markets Authority would call a “surprising term” wasn’t made clear – but either way it looks like they wanted and needed to pay in seven instalments rather than three.

You can see why they might be upset. As late as March 2023, the university was still saying that students could pay in seven. And all sorts of un-updated websites, Reddit posts and YouTube videos are still online that suggest that seven instalments are available.

Either way, the ability to pay in this way is clearly very important to many international students – and if nothing else the Teesside change generated a couple of petitions, with some students suggesting that the switch was “abrupt”:

This sudden change has put immense financial pressure on me and many other students who planned their finances according to the initial seven-instalment plan.

Flexibility matters

We reached out to the university, which said that “unlike several universities in the sector”, it offers international students the option to pay their fees in instalments to give them “greater flexibility” over their finances:

We moved from seven to three payment instalments at the start of the academic year 23/24. This is more in line with sector practice and addressed a common issue of late final instalments impacting on students’ ability to attend graduation. All students and applicants were notified of this change via regular student and applicant communications, ahead of their enrolment date.

It also told us that it understands that students’ individual circumstances will differ, which is why it has also agreed over 2,000 bespoke payment plans to further support students.

And on the currency issue, it says it has made “every effort” to support affected students to mitigate the impact of the crisis on their learning experience:

We have offered students an individual meeting with specialist staff; around 160 students have now met personally with staff and solutions have been found to support them to continue or complete their studies. We have also worked closely with community organisations to ensure there is a wide network of support available for those students who find themselves in financial hardship. Most students have taken up the support and flexible payment options offered, but unfortunately, we do have a small number of students who remain withdrawn on financial grounds and as a consequence are no longer eligible for visa sponsorship.

One other thing – some of the video material talks of the significant impact on mental health.

I’ve not seen or been party to any of the comms in this case, but generally while DfE’s Higher education mental health implementation taskforce continues its work on sensitive comms (and support) over academic results, there’s no sign in the minutes that parallel work on sensitive comms (and support) over financial issues is being done – especially important when said comms relate, ultimately, to deportation.

The department might need to meet with the Home Office to do that – given the way in which the HO finger points blame back at institutions in these sorts of cases:

The Home Office said a decision to offer or withdraw visa sponsorship rested with the sponsoring institution. A spokesman said wherever a visa was shortened or cancelled, individuals should “take steps to regularise their stay or make arrangements to leave the UK.

Add it all up, it looks from here that Teesside has almost certainly done as much as it can to help students within the confines of the role that it’s placed in by UKVI. And that is also something that’s true around the country as other versions of these styles of story pop up.

Where that gets us to, though, is still particularly unsatisfactory – and so it becomes crucial that we think through how to prevent these situations from happening to begin with.

Did they know?

Whenever I’ve written on this before, at least some of the below the fold commentary suggests that students are adults and that the information was available. I keep seeing evidence to the contrary – but regardless, it speaks to a need to not just test students’ aptitude for the English language, but to more robustly test the outcomes of all of the information, advice and guidance efforts of everyone from agents to universities to UKVI to work out if it… worked.

There’s also something important to be said for the sector acting collectively, with what may soon be a more empathetic government, to properly account for and address situations when entire countries’ currencies collapse. For me, morally, that is the minimum price of depending on students’ fee payments when we target countries where that is more likely to happen than the countries we’ve been fishing in to fund HE prior. Currency fluctuations should have their own chapter in the international education “strategy”.

We need some clarity and enforcement from either the CMA or OfS on whether things like installment options form part of the “material information” that should apply at the point an offer is made rather than when someone’s in an enrolment queue. We need a consensus around installments in general.

And regardless of the argument in the Teesside case about how these students were treated, I’ve been shown far too many threatening, heartless and really quite unpleasant examples of emails from university finance departments – many of which remind students that the university is an agent of the state – threatening students over late payment. And too many tales of the fallout from that landing on the desks of international teams that are no bigger than before the PGT boom, or SU advisors/officers deployed as a way of picking up pieces when they usually can’t.

I suspect that the more cases like this crop up, the more that activism – often not through the polite meetings with the SU – will pop up. Addressing its root causes, the incentives and the tactics used to get students to the UK matters. The stakes – especially for international PGTs – are just too high to blame them, or depend on complaints systems designed for undergraduates and home students who can have another go if it all goes wrong.

As Yemi Soile from Nigerian Students’ Union UK puts it:

People have decided to come all the way here. They sell their properties, they leave everything, and then we’re telling them to go back, just like that, to nothing?