Universities are keen to claim precedence over others – witness the shenanigans about which of UCL and King’s College London was first, and whether they or Durham were England’s third university – and Oxford colleges are no exception.

University College Oxford may (rightly) claim to be the oldest college in Oxford or Cambridge – but St Edmund Hall claims to be “the oldest surviving academic society to house and educate undergraduates in any university.”

A governance intermission

I know that the Wonkhe readership includes a fair number of governance buffs (I chose the kind word, being one myself), so a little digression is called for. Oxford has two types of educational bodies within the university: colleges and permanent private halls.

Colleges are autonomous and governed by their fellows; permanent private halls are ultimately governed by the religious body to which they are affiliated. But permanent private halls have a medieval predecessor – the academic hall. This was a body which provided teaching and accommodation for students, just like a college, but which was run by its principal, without fellows having a say. There were loads of academic halls over the centuries but typically they did not have an endowment, so relied upon the managerial skills of their principal, and the vicissitudes of student recruitment (sound familiar?).

By 1600 there were only eight academic halls left, and of these eight some became colleges; some merged with colleges, and some closed. St Edmund Hall was the last to become a college, attaining this status in 1957. From the sixteenth century, it had been overseen by neighbour Queen’s College Oxford.

Who was St Edmund?

A fair few universities and colleges are named after saints, but not many can claim a direct connection. St Edmund was Edmund of Abingdon, born about 1175, and in the 1190s a teacher in Oxford, in a house on the site now occupied by St Edmund Hall. He studied in Paris and then returned to teach in Oxford with an international scholarly reputation.

In 1222 he became treasurer to the Bishop of Salisbury, and by 1233 the Pope had appointed him Archbishop of Canterbury, imposing him on the see after King Henry III, who was at war with the barons, had had three nominations rejected. Edmund negotiated a peace (by insisting the King sack his troublesome advisor) and then did archbishop-y things for a few years before dying in France en route to Rome, in 1240.

The nearby Cistercian abbey seized the opportunity, and politicked for him to be canonised so that they could extract income from pilgrimages. Some of the normal processes were set aside, and in December 1246 he was made a saint: a very fast turnaround. One of his arms can be found today in the chapel at St Edmund’s Retreat, Enders Island, Connecticut; the fibula of his left leg can be found in the Shrine Chapel of St Edmund’s College, Ware.

Back to the hall

As academic halls were not corporate bodies, evidence about their foundation is scarce. There’s a reference to it in a rent-roll of 1317; the first of the sixty known principals of the hall was William Boys, in about 1315. In the previous century, there is evidence of land and buildings on the site being sold between families who were likely to have kept an academic hall; control passed to the church.

Importantly, the hall admitted undergraduates. This was not the norm at the time – colleges were for masters, who had already completed some university studies. And this, then, is the basis for St Edmund Hall’s claim for primacy as the first institution to house and educate undergraduate students.

English history shows the dangers of being associated with the church during the reformation. Monasteries and abbeys were dissolved; assets were stripped. By 1531 Queen’s College had obtained a lease on the site from Oseney Abbey, but in 1546 St Edmund Hall was sold by the crown. The new owners installed as principal one Ralph Rudde, rector of St Ebbe’s and vicar of Cropredy, and more significantly a former fellow of Queen’s who had been expelled. This must have been an uncomfortable situation, resolved in 1557 when Rudde died. By this stage the provost of Queen’s had bought the freehold to St Edmund’s, and transferred it to Queen’s College. And from this point St Edmund Hall was under the tutelage of Queen’s.

For the next few hundred years St Edmund Hall continued its teaching. Its strong links to religion mean that it was affected by religious trends; it was associated with the Lollards; one of its principals (William Taylor) being burnt at the stake as a heretic. Another Lollard principal fled to Prague, and became associated with Hussites and Taborites (a militant subset of Hussites). Later the hall hosted non-jurors – those who refused to swear allegiance to the crown after 1688 – and in the nineteenth century, evangelicals.

By the nineteenth century reform was on the cards. The University of Oxford had a royal commission and new statutes; there were moves to close St Edmund as the last remaining academic hall (the creation of the category of unattached students, as we have seen elsewhere, removed the rationale for bodies other than colleges). But it was thriving, and attracted some support; its principal Edward Moore fought for the hall’s continuance and, after gaining the support of the university chancellor, Lord Curzon, a university statute was passed in 1912 which guaranteed the independence of St Edmund Hall.

In the twentieth century the Hall slowly became more formalised, with a body of trustees entitled to hold property on its behalf, and a relaxation by Queen’s College of its control. In 1937 the University became trustee for the hall, and a fellowship of ten was entitled to elect the principal. The process was completed by 1957, when it became a college of the University in its own right, but retaining the name St Edmund Hall, in honour of its heritage. It admitted women as students in 1978.

The college has an excellent account of its history on its webpages.

It’s for charity

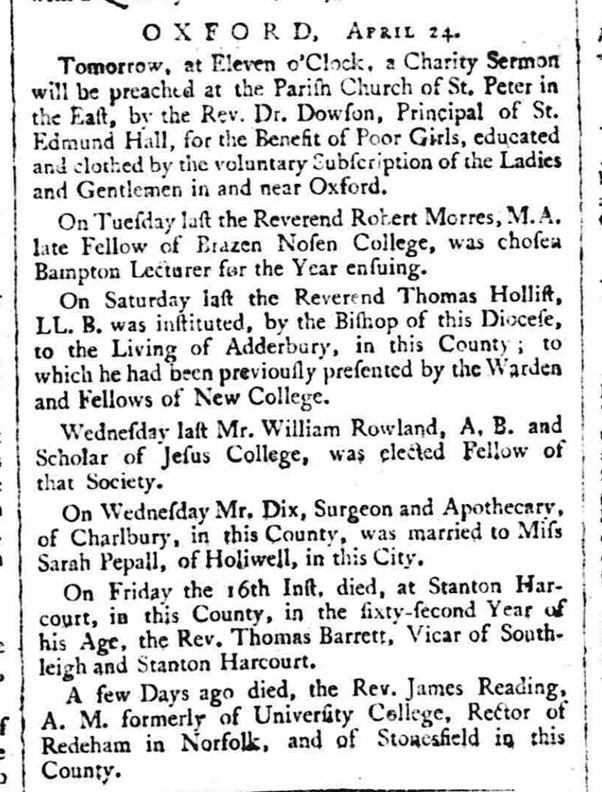

Here’s a nice snippet: an extract from the Oxford Journal of 24 April 1790.

The notice records Dr Dowson, Principal of St Edmund Hall, preaching a charity sermon at St Peter in the East (the church which is practically embedded in the fabric of the Hall, and which since 1970 has been the college library), for the benefit of poor girls, educated and clothed by the voluntary subscription of ladies and gentlemen in and near Oxford. The Live Aid of its day. And note also the fabulous reference to Brazen Nosen College.

Whatever became of him?

St Edmund Hall – or Teddy Hall, as it is more informally known – has many famous alumni, including leading international exorcist Jeremy Davies; Python Terry Jones; and journalists Sophy Ridge and Samira Ahmed.

Another former student is a barrister who, as you read this on 5 July, will be gearing up either for Prime-Ministership, tricky negotiations, or ignominy, depending on how things have gone overnight. Keir Starmer undertook postgraduate study at St Edmund Hall, after graduating in law from Leeds.