Aficionados of 1970s TV sci fi may recall that 13 September 1999 is a significant date: it’s when an accidental explosion sent the moon out of Earth’s orbit, beginning the adventures chronicled in Space 1999.

Bear with me here: as Perry Mason would say, I’ll show relevance. Space 1999 was created by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson, who were also the creative force behind such marionette-based capers as Thunderbirds, Stingray and Captain Scarlet. And Sylvia Anderson studied at LSE, depicted in today’s postcard, although it seems that like Mick Jagger she never completed her studies there.

LSE is the epitome of an urban university. There is a campus of sorts, although in truth it is simply a collection of buildings within a small area number of streets off the Aldwych in London. William Beveridge, of whom more later, described LSE as “an institution on which the concrete never sets,” and this remains true today: LSE now is unrecognisable as the school I attended in the 1980s. Sic transit gloria mundi.

LSE is and always has been a political institution. And into politics we must go, to understand LSE’s foundation and history. Let’s start with a Roman general – Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus. His delaying tactics in the fight against Hannibal’s invading army inspired guerilla movements everywhere and, in the 1880s, his name was chosen for the Fabian Society to represent their reformist and gradualist approach to democratic socialism.

The Fabian Society, on 2 August 1894, received notification of a bequest of about £20,000 from a Derby lawyer, Henry Hunt Hutchinson, “that they may apply the same at once, gradually, and at all events within ten years to the propaganda and other purposes of the said Society and its Socialism, and towards advancing its objects in any way they deem advisable.” Sidney Webb was the chair of the trustees of the bequest, and his vision was for the foundation of the London School of Economics and Political Science – he persuaded the trustees that this should be a focus of the bequest. And so it was: the LSE was founded, and accepted its first students in 1895.

The first prospectus set out the mission:

the special aim of the School will be, from the first, the study and investigation of the concrete facts of industrial life and the actual working of economic and political relations as they exist or have existed, in the United Kingdom and in foreign countries.

It sought to replicate in the UK the approach to social sciences of Sciences Po in Paris and Columbia University in New York.

Webb was one of the four guiding minds for the early school: Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Graham Wallas, and George Bernard Shaw (yes, that one). Initially the school operated from John Adams street, off the Strand; it them moved to nearby Adelphi Terrace. But on joining the University of London in 1900, a more permanent home was needed, and Clare Market, just off the Aldwych, was the location for the first building.

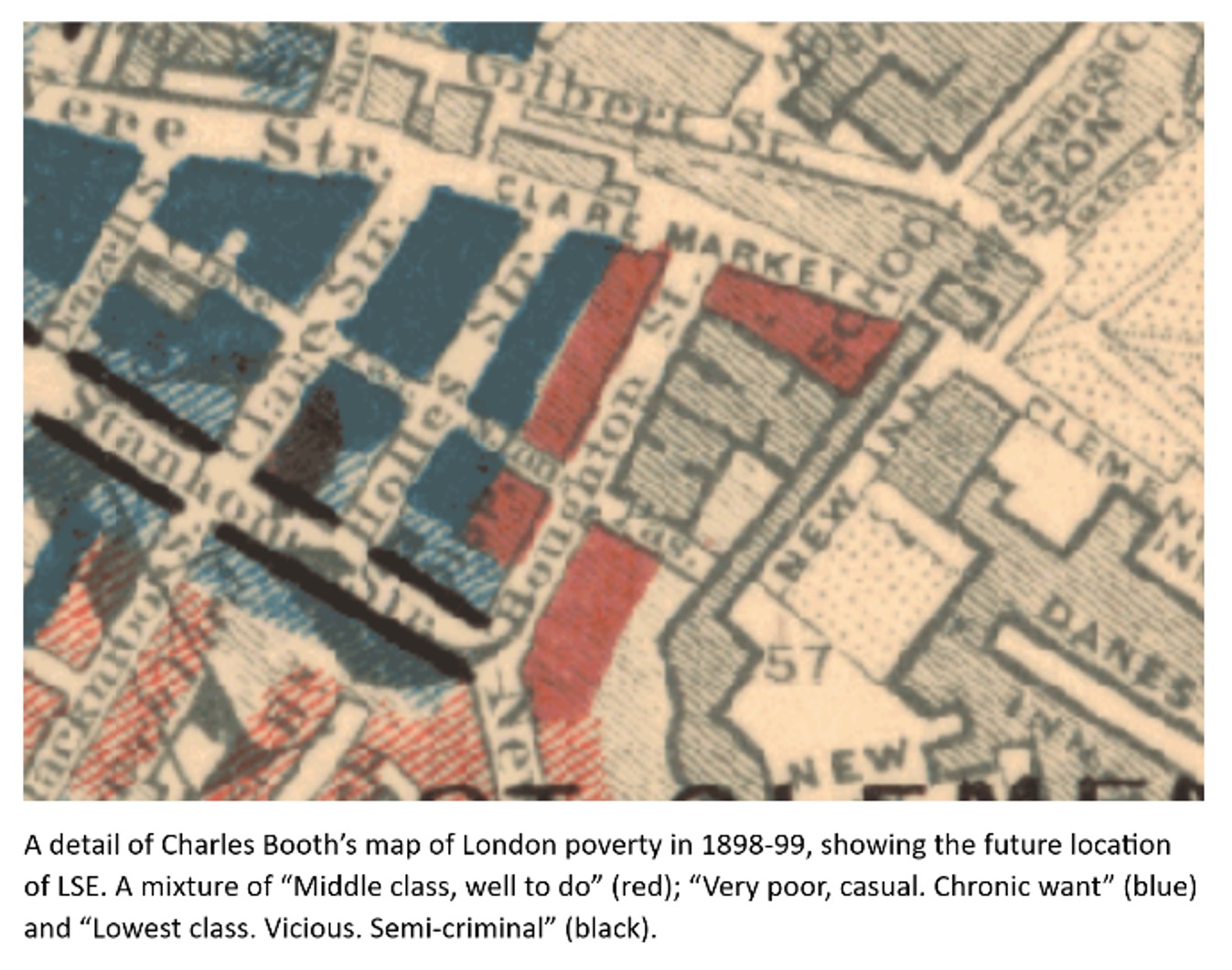

At that time Clare Market and surrounding streets were dense housing, as well as being near the law courts and Lincoln’s Inn. The remodelling of the 1920s which brought Kingsway and Aldwych into being had not yet taken place. But it was a home.

The school grew slowly and developed. Lots of new buildings, but all of them essentially expansion on or around Houghton Street. (The postcard, by the way, shows the extractor fan on the outside of what used to be the Three Tuns, the students’ union bar, in what was the Clare Market Building. Now gone, I fear.)

But the story of LSE is really the story of people and knowledge. Let’s highlight a few.

Firstly, I promised to come back to William Beveridge. Director of LSE between 1919 and 1937, Beveridge was a social reformer and the architect of the British welfare state. His 1942 report identified ways to fight the “Giant Evils of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness” – it was the foundation for the 1945 Labour government’s reforms.

Now lets mention Lilian Knowles – the first woman to hold a professorship at LSE, and the first woman to be dean of one of the University of London’s faculties. Knowles had been at LSE right from the beginning, enrolling as a research student in 1895, and progressing as lecturer, reader and then professor in 1921. Her husband’s biography of Knowles, in a posthumously published second volume on the economic history of the British Empire, wrote:

An ardent supporter of any movement that made for equality of opportunity as between men and women, she [Knowles] marched in no suffragette processions, still less did she intend to go to gaol for her principles, although she would cheerfully have done both had she thought any good purpose would have been served thereby. But she held that she was doing more good to the cause by showing that she, a woman, could do a man’s job as well as any male creature and better than most.

Another name to notice is Walter Adams, school secretary from 1938 to 1939 and then director from 1966 to 1974. Firstly, note that this is an example of a move from professional services to institutional leadership. There’s not many of those about. Secondly, Adams had an extraordinary career. His period as school secretary ended when he was appointed to a senior role in the intelligence services. After the war he became secretary of the Inter-University Council for Higher Education Overseas; and in 1955 was appointed principal of the newly-established University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (which became in time the University of Zimbabwe). When he was appointed as the LSE’s director there were huge protests from students, in 1967 and 1969, including a 25 day occupation of the Old Theatre. His connection to the brutal Rhodesian regime was the spark. Adams’ appointment was not cancelled, but the principal of student involvement in school committees and decision-making was secured.

We should mention Sir Arthur Lewis – St Lucian economist and Nobel prize-winner, who became in 1938 the first black member of LSE’s academic staff, and whose thinking highlighted what would become better known as globalisation. We should note Lionel Robbins, student and then professor of economics at LSE, who amongst other things chaired the committee on higher education which, via the Robbins Report, set the framework for the expansion of higher education in the UK in the 1960s.

An on a personal level, we must notice Karl Popper, one of the great names of twentieth century philosophy, who was appointed to LSE in 1946 and was professor of logic and scientific method until his retirement in 1969. Popper’s influence on the department of philosophy, logic and scientific method at LSE was still strong when I studied there from 1986-1989: and in fact he gave his inaugural professorial lecture at LSE in 1989, it not having been possible to do so in 1949.

Popper was then 87; his most recent work was a piece (published as A World of Propensities) positing, amongst other things, a form of intelligence in trees. The event coincided with a reunion of 1950s alumni from the department, and (sensibly) the arrangement was that he lectured in the old theatre, to the old alumni. The new theatre in a different building had a one way video link (we could see and hear him, but not ask questions) and current staff and students were sat in there. This ensured that the questions were not as hostile or challenging as they might otherwise have been; it was a kind decision.

And finally Minouche Shafik: LSE director from 2017 to 2023; renowned economist at the World Bank and the Bank of England; and president of Columbia University from 2023 to 2024, when she resigned following strong criticism of how she had handled pro-Palestinian student demonstrations on campus.

There are more names that I could have mentioned, but that will, perhaps, do for now. What I find interesting is how central LSE is and has been to British public life since World War Two, but how few leading politicians have studied there compared to Oxford (particularly) and Cambridge. The only LSE alumnus to be Prime Minister is the fictional Sir Jim Hacker. Perhaps this is the Fabian influence still at play – do things that work, not necessarily do things that are dramatic.

In writing this blog I’ve drawn on, linked to, and found very helpful the fabulous series of pieces written by Sue Donnelly, former LSE archivist, as part of LSE’s 125th anniversary celebrations. You can find lots more resources here.

Wow Hugh, what a fantastic read over my morning cuppa here in Toronto. I may be a million miles from Houghton Street, but the LSE and the friends I made there are all in my heart. Thank you for lots of new info and for refreshing my memories 🙏🏼🥰