Securing graduate employment outcomes has become increasingly central to the mission and accountability metrics of higher education. And so the search has been on for a silver bullet for graduate employability.

Over the last few years there has been an increasing recognition that extended work placements, including both the year-in-industry approach and shorter summer or Easter internships, might hold the key.

Placements are valuable because they operate on multiple levels, providing students with new skills, a stronger ability to contextualise their learning, enhanced social capital and social mobility, genuine work experience and even making them more positive about their degrees. What is more many employers use placements as a “try-before-you-buy” opportunity which allows them to work out which students they might want to hire permanently.

In 2020 employers responding to the Institute of Student Employer’s (ISE) annual student recruitment survey reported that they hire back 50 per cent of their former interns and placement students.

The problem of demand

If the universities minister or vice chancellors could legislate in favour of placements then we would probably see every student in the country taking part in one. But universities can only deliver placements if employers are willing to provide them.

Placements remind us of the uncomfortable truth, that employability is not just a higher education agenda, it is ultimately contingent on the labour market. Issues of labour market supply (the skills, knowledge and volume of graduates) have to be understood in relation to the demand that is coming from employers.

The demand for interns and placement students was dealt a very serious blow this year. As academic Stef Foley wrote on Wonkhe in June “workplace placements are now out of the question for the foreseeable future.”

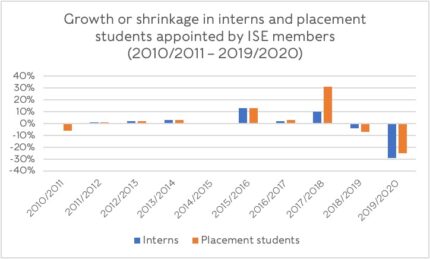

This is substantiated in ISE’s latest research. Our annual student recruitment survey found that, despite valiant efforts to move internships online during 2019-2020, employers provided 29 per cent fewer short-term internships and 25 per cent fewer placements than in the previous year.

This was the biggest drop in the availability of internships and placements that we have recorded over the last ten years, when we started gathering this data.

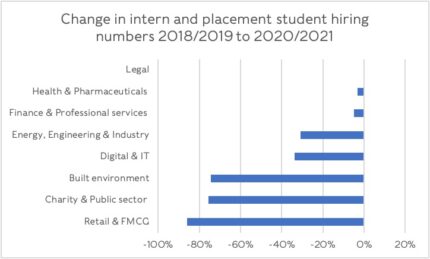

What is more the problem is not evenly spread across the economy, but is very sectoral. We asked employers to tell us how many interns and placement students they were planning to recruit next year and compared it to their hiring in 2018-2019. With the exception of the legal sector, every sector was expecting their placement opportunities to decline. In retail and fast moving consumer goods, the charity and public sector and the built environment, these falls were fairly dramatic.

For many employers interns and placement students are a nice to have, but easy to do without during hard times. The pandemic is disrupting many employers’ business and leading them to make difficult decisions about their existing staffing as well as requiring many to re-engineer core business processes.

Throw in the added complication of bringing placement students into businesses in a Covid-safe way and managing new, short-term hires remotely and it is easy to see why many organisations are reducing their commitment to internships and placement students.

How higher education should respond

The crisis in internship and placement student positions presents an immediate problem for many universities. Most will have at least some students already on or starting a programme which promises placements as part of the degree. In some cases a certain volume of placement activities may be linked to core assessment and even to associated forms of professional accreditation.

Even without this internships and placements are widely used to support student employability and transitions. Universities can’t just walk away and shrug their shoulders at the changing labour market situation.

An immediate response to this situation was found during the first lockdown. University regulations had to be flexed to allow students to continue with programmes where placements were disrupted.

Where this was handled best it was based on careful and proactive communication with employers about what could and could not be provided. In some cases this led to the development of innovative virtual internships.

But, universities also have to be honest with students, both in their marketing materials and with current students and explain that the situation has changed and that promised placement opportunities might be transformed or disappear altogether.

For the higher education sector this ultimately poses some big challenges. Programmes will need to be designed to recognise that it may be difficult to always deliver a traditional placement. Further thinking will have to go on to develop alternative and virtual experiences.

At the moment there are a vast array of different activities operating under the banner of “virtual internships”; ultimately there will need to be clearer definition about length, management, task and quality.

The challenge with placements and internships also highlights the importance of universities investing in careers services and other employer brokerage activities. The decline of placements should make close employer engagement more, rather than less, important.

Finally, it is worth considering what the sector should be lobbying for from government. So far government employment policy has pretty much ignored higher education students and graduates altogether. There is a need for this to be addressed as the recession deepens.

At ISE we have been arguing that the government needs a plan to stimulate student employment. Within that there should be a financial incentive for employers to continue to engage with internships and placements.

We fully expect internships and placements to continue to be a part of the student experience and the student employment market. But there are clearly challenging times ahead.

So much great food for thought in here and in ISE’s plan to stimulate student employment. Synergy here with UKCISA’s policy paper and proposed Graduate Export Placement Scheme – we should talk!