From where we sit – or, more accurately when on a Cross Country train over the summer, from where we stand – there are some things coming for students that it’s possible to metaphorically see from metaphorical space.

Food price inflation will distort the “average” basket of goods for those on low incomes so significantly that a fresh cost of living crisis is obviously coming.

The failure to consult meaningfully on the hundreds of micro-decisions to be made on toilets, changing rooms and anything else currently gendered in a university has the capacity to cause chaos the very second that the EHRC publishes what we can already guess it will say on the Supreme Court ruling.

In England, the Renter’s Rights Bill will see absolute chaos once everyone realises that landlords will be evicting students on or near June 1st next year. Assessment reform in an age of AI is really moving in some parts of some universities – in others, it’s as if the OHP is still being PAT tested.

And the signals from the labour market and the surveys published over the summer hold out a real prospect that student part-time work will all but dry up in several cities in the year ahead – once that way of plugging the growing hole in the student finance system is no longer available, what exactly is the plan?

Make me feel fine

Every summer, while you’re on a beach protecting yourself with factor 50, we’re out on the rail network for three months or so meeting, briefing and training the new batch of students’ union officers who won in last Spring’s SU elections.

In part, that involves thinking through the policy headwinds and identifying the ways in which SUs and their universities have factored in their own protections for the dangers that are coming. This year the dangers feel particularly real; the scenarios particularly prescient; the forward plans systematically absent.

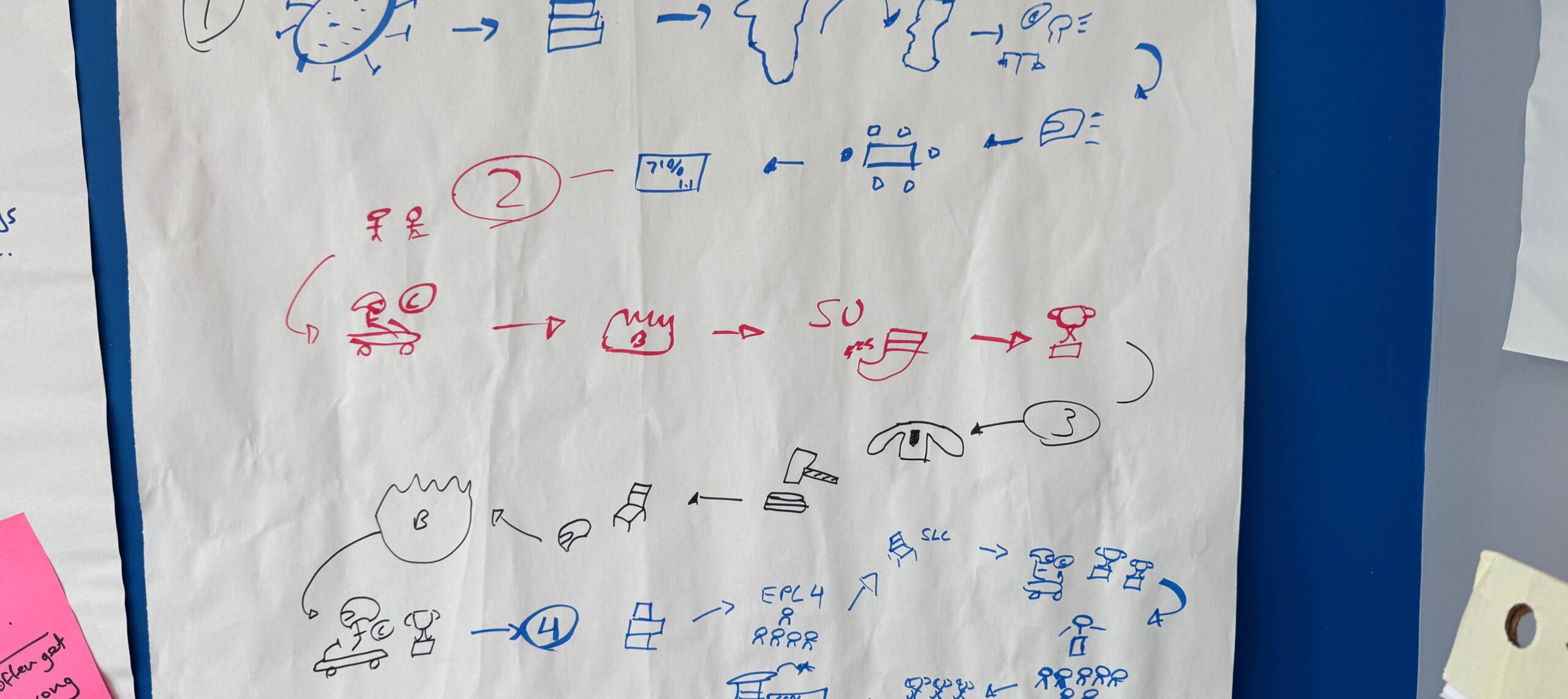

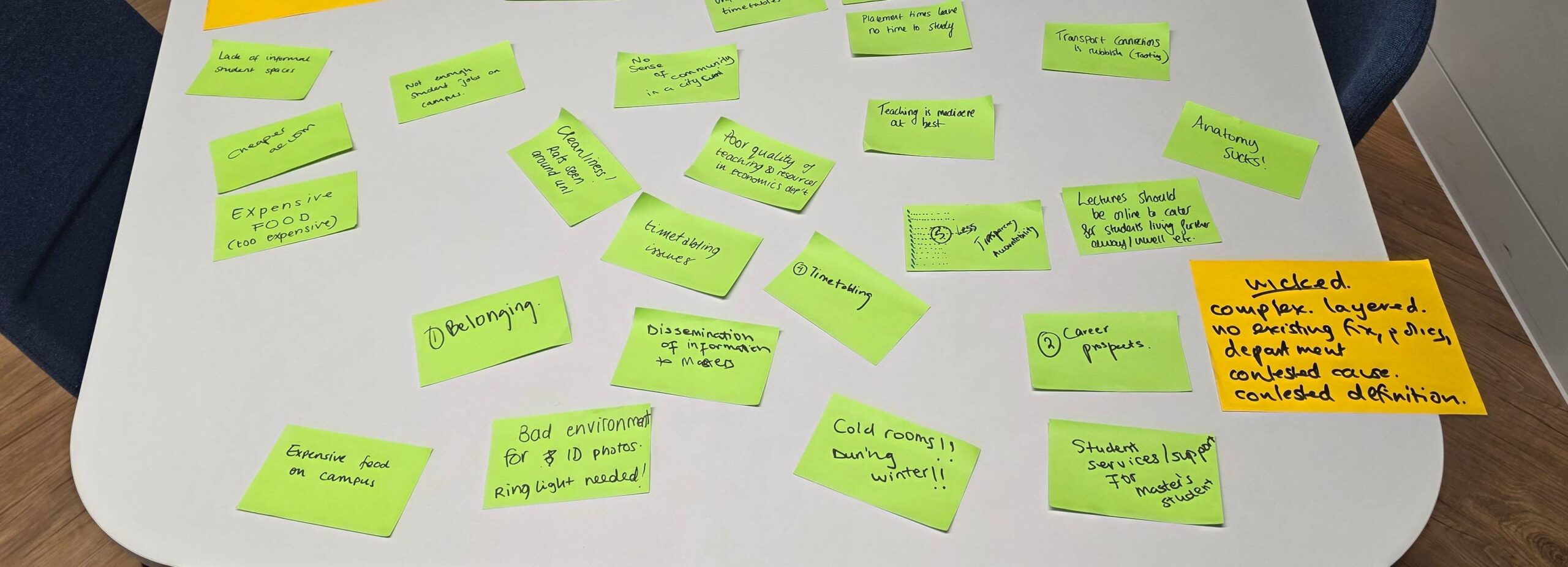

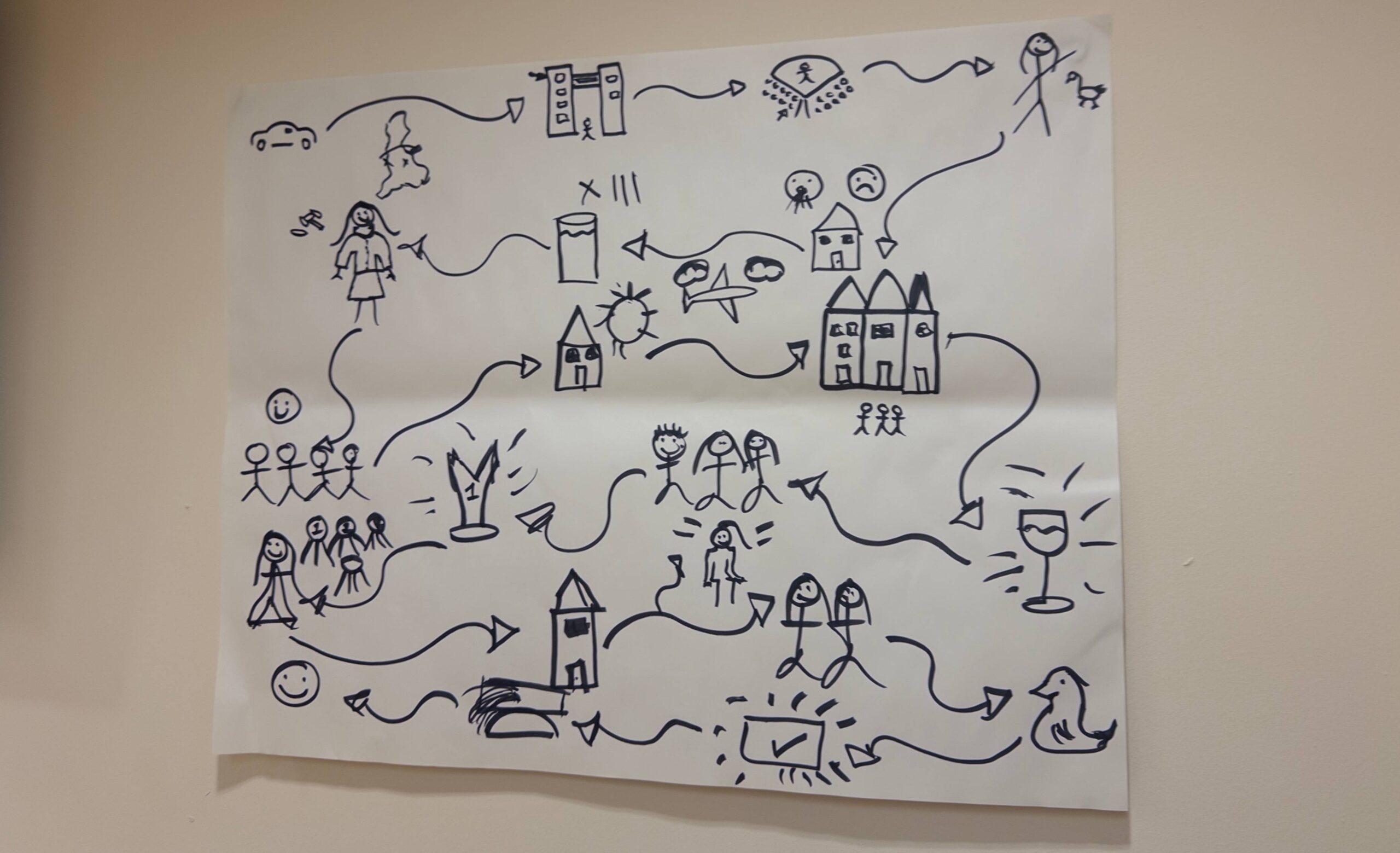

As part of almost every visit, we’ll explore the journeys that have led student leaders from welcome week to the un-air-conditioned seminar room of flipchart paper and post-it notes that prefaces their year in office.

And this year, not only do the dangers feel most alarming, and the mitigations most miniscule, but the experiences that have led students into leadership almost too awful to explain.

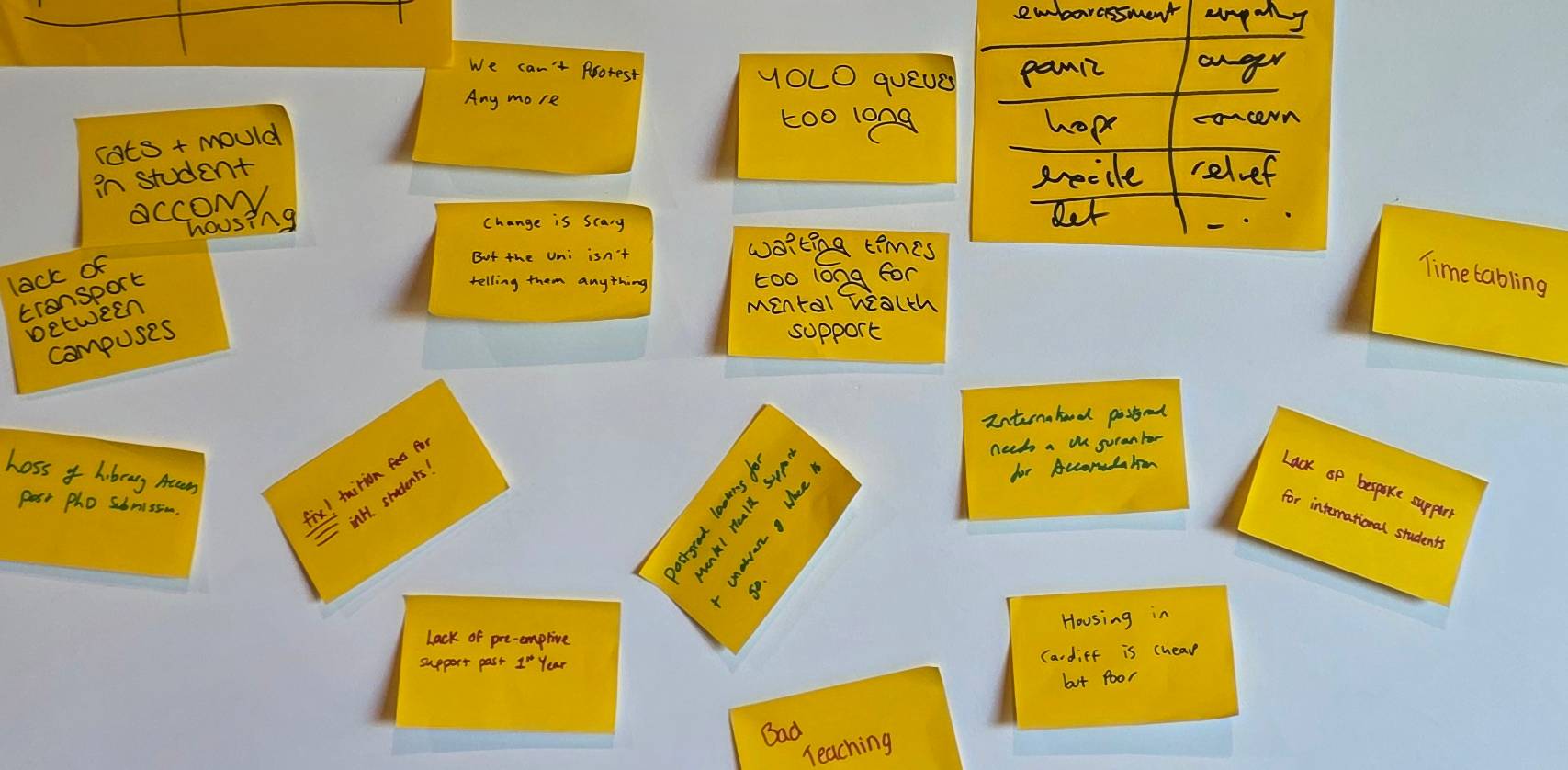

Along with everything else, this has felt like a year of extremes. Outright lies from recruitment agents. Shocking stories of disabled students having their rights crudely brushed aside. Teaching that is poor and perfunctory, supervision that is awful or absent, part-time jobs that are as exploitative as they are normalised. Tales of safety and quality in the private rented sector that are just too awful to imagine.

On one visit, we learned of rats living in a wall. On another we were told of a lecturer that “everyone knew” was a “lothario” but nobody knew how to report. International students whose visas were late, admitted weeks after the start of their course only to miss the induction, then be accused of assessment offences they didn’t know were offences, only to have their visa run out before their final work could be marked. No graduate route for them.

We’ve heard of students working below the minimum wage for weeks on end, while being bullied and harassed in the process. We’ve heard of students taking to gambling and gig work to pay fees and rent.

We’ve heard of students struggling with late and inflexible timetables, personal tutor systems that exist only on paper, late and inadequate feedback, and courses that were so stripped down and reorganised by the time they hit their third year that they were unrecognisable from that which was promised.

Fever dream high in the quiet of the night

Some of what we’ve heard will be of no surprise to regular readers. Students’ lives are now dominated by juggling – work, study, housing, travel, and survival in a way that makes “full-time” higher education feel like a misnomer. Their new leaders describe the contortions that students must go through to piece together rent payments, jobs, study hours and social life – and how universities often fail to see the whole picture.

Complaints about patchy personal tutoring, email response times, and lack of flexible timetabling all stem from the same place – a sense that systems are designed for an imagined student who doesn’t exist anymore. The result is exhaustion, anxiety, and an education experience that feels compromised rather than enriched. But they also feel like systems that neither can change nor will change as a result of their advocacy.

Cost dominates – not just for tuition, but every part of life that sits around it. Student leaders tell stories of universities insisting the cost of living crisis has passed because hardship fund applications have dipped, while on the ground students are launching swap schemes, food banks, budgeting workshops, and recipe exchanges just to survive.

International postgraduates in particular speak of being “milked” – with extortionate accommodation, opaque fees, and casual gaslighting when asking for support or flexibility. These are not isolated grumbles but systemic failures, and officers are weary of institutions that seem keener to manage perception than engage with the reality of what it takes to participate in HE.

Another set of concerns centres on space, belonging, and wellbeing. Campuses are crowded yet inaccessible – coffee queues too long, study spaces too few, and neurodivergent students locked out of the quiet they need. Student leaders are angry at the dissonance between glossy atriums and the absence of somewhere to heat up food. They’re also clear that wellbeing is not “extra” – but the way staff understand their role in relation to student mental health varies wildly, from proud detachment to amateur counselling.

Add in the “engagement collapse” – anxiety, imposter syndrome, and an erosion of confidence – and it’s no wonder that participation in both classrooms and communities feels fragile.

Student leaders want something deeper – a recognition that employability, citizenship, and belonging are not bolt-ons, but core to the experience. They want placements, volunteering and democratic activity to be credit-bearing, not just because they deserve recognition, but because participation costs time and money they don’t have. But they don’t really think they can have it.

They want universities to stop pretending belonging can be conjured through branding, and to grapple instead with consistency, delivery and equity. And they want honesty – not just reassurances that budgets are fine, but genuine partnership in facing the future. Without that, the visions of sector leaders – blueprints, reviews, strategies – risk being hollow. University survival will be pointless if students don’t.

Devils roll the dice, angels roll their eyes

There’s always – especially for Jim – a touch of plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. Perhaps some of what’s experienced as a problem or barrier is just a rite of HE passage, a part of growing up, a component of joining a large and diverse community that involves setbacks and coping and developing resilience in the face of adversity.

But as the flipchart sheets describing the journeys are pinned to the wall mid-each morning, we have wondered whether there’s something else going on.

The year before Jim began spending his summers like this, a couple of early career social psychologists from Yale had published a paper that ended up having quite the impact on some of his psychology student colleagues in the mid 1990s.

Josta and Banajia’s “The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness” doesn’t sound like the most fun a Media and Cultural Studies student can be having over a photocopier, but his accidentally interdisciplinary first-year had meant Jim was able to get into all sorts of things that were never originally on the curriculum.

The paper illustrates the idea that people, including the disadvantaged, often internalise stereotypes or explanations that legitimise their own oppression. It shows experimentally how individuals and groups can end up rationalising harmful arrangements – believing the powerful are more competent, attributing failure to themselves, or normalising unequal roles.

It has helped to shape exercise design and training approaches for new student leaders ever since. Change isn’t just about better evidence arguments or slicker campaigns – it’s about creating the conditions for awareness and solidarity, surfacing the arbitrariness of rules and hierarchies, and showing that misery is not inevitable but manufactured.

When students see that struggles with housing, finance, or assessment aren’t personal failings but systemic outcomes, the pressure to internalise blame weakens – and the potential for collective action grows.

That matters because normalisation is the enemy of change. If students “learn to love their limitations,” policymakers have little incentive to do better. The lesson has always been that sometimes the most powerful intervention isn’t a tidy solution or a polished set of recommendations, but the act of refusing to let the intolerable become invisible.

Consciousness-raising, storytelling, and solidarity are not soft tactics – they’re the preconditions for breaking the cycle of silence that otherwise guarantees next summer’s flipchart sheets look the same as this year’s.

No rules in breakable heaven

Yet this year more than most, we have at times felt like we’re swimming against a tide that is too strong to mount a defence against. Because the truth is, even though the stories are well beyond the mild irritations and petty bureaucracy of the past, they almost all sound like secrets. They are, to put it another way, below the iceberg’s surface.

Part of the problem is that the UK has an increasingly old electorate. Older voters are less likely to have direct contact with universities, less likely to hear unvarnished student stories, and more likely to see the sector through the prism of cost rather than value.

If the most shocking aspects of student life remain whispered rather than shouted, they never cut through to those who wield electoral influence – meaning the ballot box skews policy towards pensioner bus passes rather than student housing reform. The silence isn’t just cultural, it is political.

There’s the country’s economic climate – higher education is operating in a state that is literally running out of money. Public finances are squeezed, universities are struggling with deficits, and the instinct everywhere is to protect what you have rather than admit to new liabilities.

When uncomfortable truths about student experience are not voiced, it becomes easier for managers, ministers and mandarins to avert their gaze, telling themselves that problems can be absorbed rather than addressed. Silence functions as an accidental subsidy – by not surfacing the costs borne by students, the state and the sector get away with shifting more burden onto them.

Universities themselves are complicit, albeit we suspect unintentionally. A manager at any level who admits that their students are hungry, homeless, or harassed risks reputational damage, league-table drops, and hostile headlines. Better to stress resilience, opportunity, and the odd bursary scheme than to admit systemic failure.

But the reputation-management reflex actively undermines the case for investment. If every institution projects that all is broadly fine, why should Treasury officials prioritise a bailout? Silence, again, becomes a strategy – but one that entrenches scarcity rather than securing resources.

The cumulative effect is a system where student misery remains invisible to those with power, not because the evidence is lacking, but because the incentives to reveal it are weak. Students stay silent for fear of stigma, SUs temper their tone to keep the block grant flowing, universities bury problems beneath polished prospectuses, and policymakers hear only satisfaction scores.

The loop feeds itself – and in a democracy where older voters decide priorities, absence of noise is all too easily interpreted as absence of need.

Hang your head low in the glow of the vending machine

For student leaders, the pressures are especially acute. Their role is ostensibly to represent the unvarnished experiences of their peers, but they operate in an environment shaped by the logic of LinkedIn – an arena where polished professionalism is prized, and the temptation to smooth away awkward truths is ever-present.

To admit publicly that your students are hungry, unsafe, or disillusioned can feel incompatible with the personal brand of competence and leadership that young people are told they must cultivate if they want graduate opportunities. The very platforms officers use to communicate are biased towards optimism, progress, and positivity – which makes surfacing struggle feel like self-sabotage.

Even when they’ve tried, they’ve been hit by the devious frames – denialism (it is not a problem), normalisation (it is normal and expected) and victim blaming (it is a problem because of the individual mistakes), all of which become “how we operate around here” and thus hard to even start to tackle.

And that takes us right back to Jost and Banaji’s arguments about system justification and false consciousness. If social media teaches student leaders to internalise the idea that problems are personal weaknesses rather than systemic failures, their capacity to challenge those failures is blunted.

When representation becomes curation, the cycle of silence is reinforced – not because officers lack courage, but because the psychological and cultural currents around them steer towards self-preservation over truth-telling. Breaking the cycle means supporting officers to resist the currents, to value solidarity over self-presentation, and to recognise that authentic voice is more powerful than polished image.

It’s why the conspiracy of silence that surrounds the contemporary student experience is so dangerous. It erodes the sector’s long-term sustainability by masking the very crises that could galvanise public support. In an ageing nation with empty coffers, the only way to win investment is to make the case that students’ struggles are real, systemic, and intolerable – and to do so loudly.

If higher education keeps choosing discretion over disclosure, it will discover that in the competition for scarce resources, quiet constituencies get ignored first. Maybe it’s discovered it already. But it’s never too late to tell the truth.

Banger article, thank you!

Fantastic article. This conspiracy of silence, brought on by fear, is why I’m getting sick of this sector. We can all admit the problems behind closed doors in staff meetings. We know that only government action will make things better. But instead we get vice-chancellors writing for THE about how universities need to make economic-driven choices in order to survive, the UCU blaming vice-chancellor pay and VCs in turn talking about the financials of their institutions. We all know what’s really going on, what we really want, what will actually make things better for students. No number of voluntary severance… Read more »

Absolutely bang on! Regrettably the whole system is designed (intentionally so) to keep the students quiet and compliant. This is even more true for “professional” 🤥 (sic) degrees where course leaders at the end of the course sign off students as “fit and proper” people to be let into the job role. Don’t even dare think about challenging the status quo!

Titanic