Elite universities struggle to attract a mix of students that is broadly representative of society.

Part of the challenge to changing this is understanding the degree to which what and who may influence students’ higher education decision-making and university destination.

Existing research indicates that the advice and support of teachers have a significant impact on student choices and applications to higher education.

Once a young person from a very disadvantaged background, I haven’t always understood exactly how and why going to university could be transformational for the life outcomes of those from backgrounds like my own – my dad a domestic appliance engineer, my mum a stay-at-home parent for six children, living in a cramped council house.

I certainly never experienced personal teacher encouragement to consider applying to university and only thought this could be a reality for me, when my own mother went to Oxford Polytechnic (now Oxford Brookes University) as mature student, when I was 15.

By the time I made the long journey to university myself, I was 24. With no available familial financial support and caring responsibilities, I felt restricted as to where I could apply and despite living and going to school in Oxford, the university here was simply not even on the radar.

When I was eventually accepted to the University of Reading, I remember my dad saying, with some element of pride in his voice, “that’s a red-brick university” and having no idea what on earth this meant.

To me, Reading was one of three universities that fitted my first priority of being commutable and secondly, offered a course that roughly matched my interest. Being “a redbrick university”, whatever that meant, was not part of my thinking, but simply a coincidence.

Although Reading was a great university, looking back, if I’d have had “that teacher” who inspired and actively supported me to apply to university, I can only imagine what other options there might have been, where else I might have applied and what else I would have achieved.

Passion without professional development

Knowing university had transformed my own life, I became a teacher with a deep passion for supporting young people, particularly those from backgrounds like my own, to get there too.

However, I knew very little about how to support progression and even as a Deputy Head of Sixth Form, received no formal professional development in supporting students’ university pathways, often simply drawing on my own existing knowledge and experiences, alongside those of my colleagues.

Whilst I certainly had the best intentions for my students, I did not have the best knowledge and understanding needed to guide and support them to make fully informed decisions about their university destinations.

With a passion for improving university outreach for this influential group, in 2020-22, I investigated the backgrounds of teachers in state schools and the influence this may have on how frequently they advise their students to apply to Russell Group universities and the University of Oxford.

I also investigated knowledge capital relating to the University of Oxford and the admissions process to support student progression.

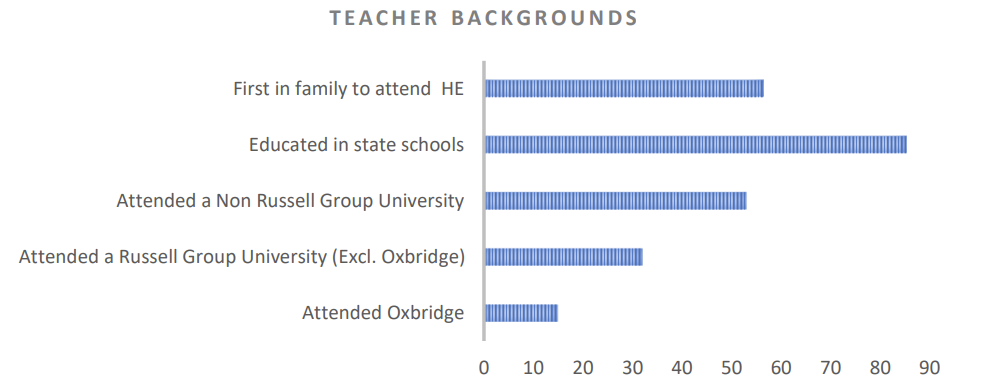

109 teachers from state secondary schools in Oxfordshire and the northeast of England with existing outreach links to Trinity College (Oxford) completed an anonymous cross-sectional quantitative online survey. These teachers were from a range of social and educational backgrounds:

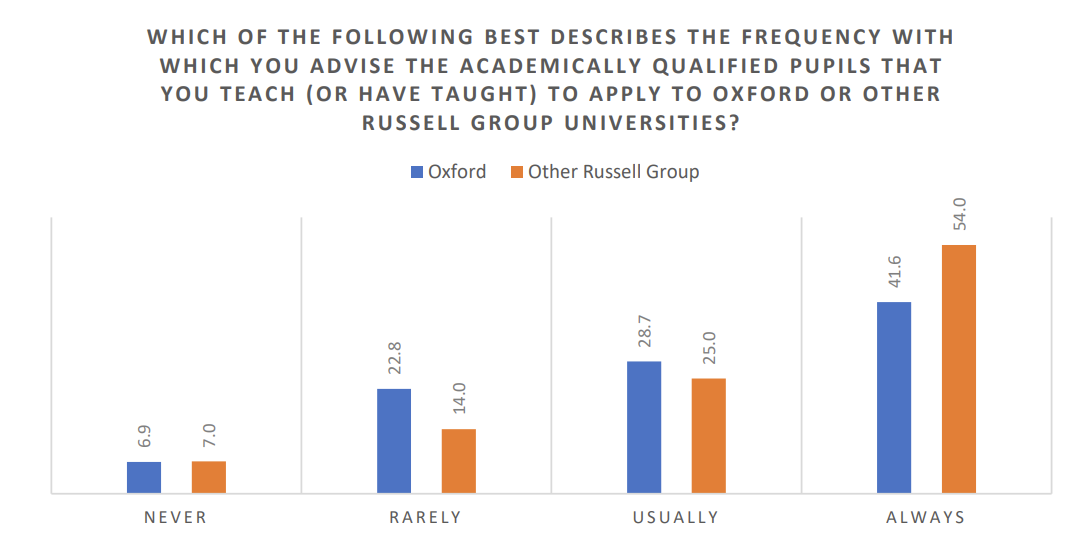

The survey included questions from the original 2016 Sutton Trust teacher poll that were adapted specifically for Oxford and the Russell Group universities. Responses were more positive than those published in the original poll, where some 43 per cent of state school teachers either rarely or never advised their “academically gifted” students to apply to Oxbridge.

Nonetheless, my own findings showed teachers advised qualified students to apply to Oxford significantly less frequently than other Russell Group universities – just 41.6 per cent of teachers said they always advised their academically qualified students to apply to Oxford, compared to 54 per cent of teachers who always advised Russell Group universities.

For usually advising Oxford or the Russell group, the figure was 28.7 per cent and 25 per cent respectively. And 29.7 per cent said they rarely or never advised their students to apply to Oxford, whilst 21 per cent said they rarely or never advised their students to apply to the Russell group.

Whys and why nots

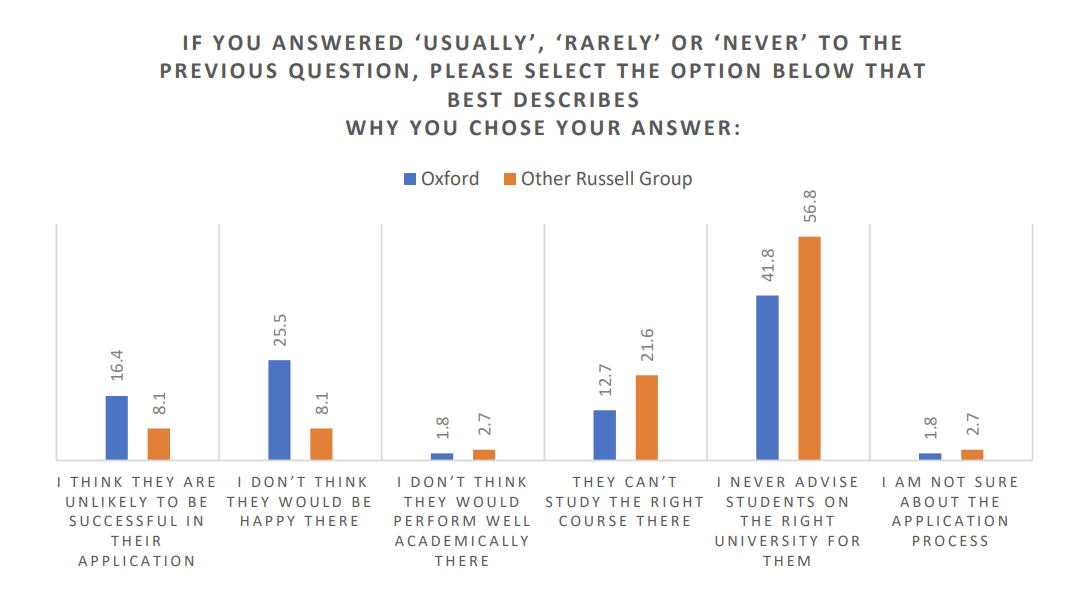

Explaining why they didn’t always advise qualified students to apply to these different types of university, 16.4 per cent of teachers said they didn’t think their students would be successful in their applications to Oxford, compared to just 8.1 per cent of respondents when asked the same question about Russell Group universities.

25.5 per cent said they didn’t think their students would be happy at Oxford, however, just 8.1 per cent thought this would be the case for students at other Russell Group universities.

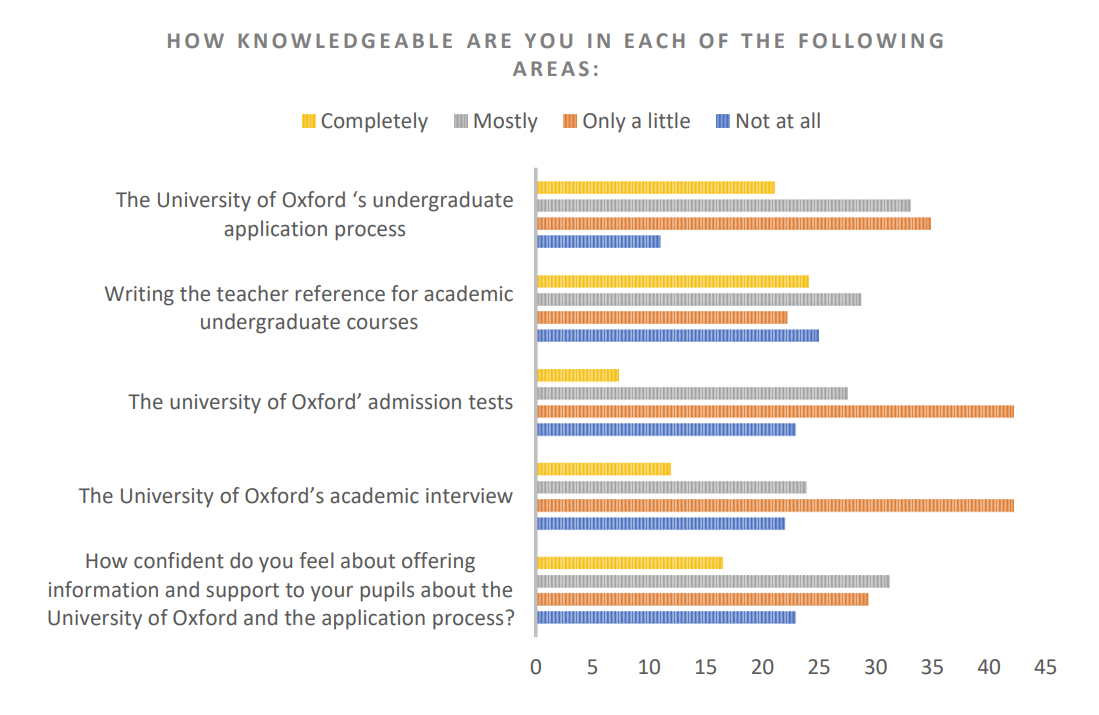

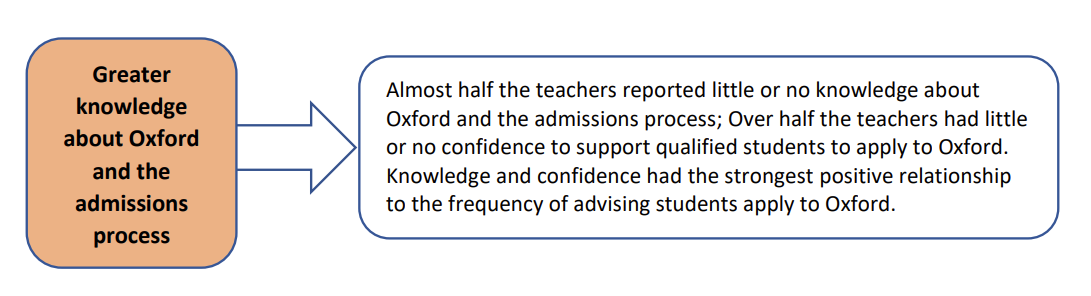

Just 1.8 per cent and 2.7 per cent stated uncertainty about the application process was why they did not always advise their students apply to Oxford or other Russell groups, respectively. However, when asked specifically about Oxford admissions, 46 per cent, 65 per cent and 64 per cent of teachers said they felt only a little or not at all knowledgeable about the general process, the admissions tests, and the academic interview respectively.

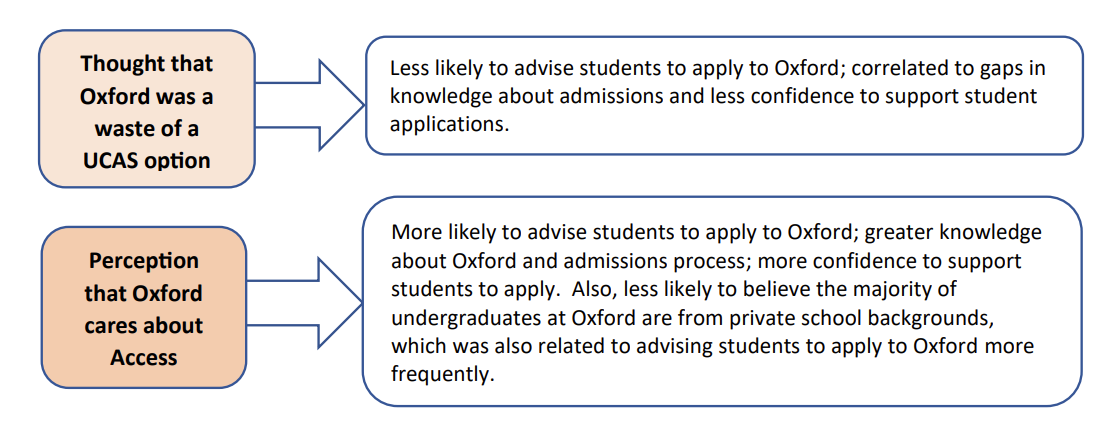

A mix of perceptions about Oxford seemed to influence how frequently teachers advised their academically qualified applicants apply – that students may not be as happy there as elsewhere; or that Oxford does not care about increasing access to those from state-school backgrounds.

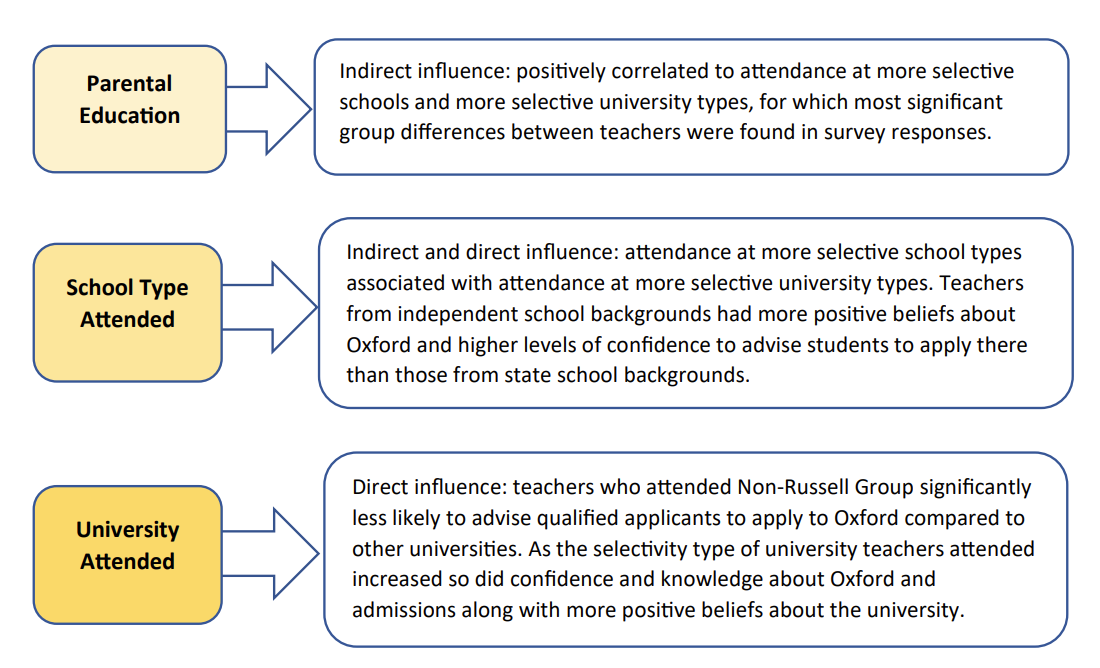

Teachers own social and educational backgrounds had varying degrees of influence over how frequently they advised their students apply to Oxford or Russell Group universities:

Sharing identities

My findings show that state schoolteachers often share the social identities of their students (first-generation, state school educated), do not all possess the educational experiences needed to confer knowledge capital, are as equally likely as students to struggle to see how people like “us” can both access and thrive at the most selective universities, such as Oxford.

Just as we do for students, we should develop long-term teacher programmes that:

- Demystify the admissions process and traditions known to alienate underrepresented groups address concerns about wellbeing and the likelihood that those from underrepresented backgrounds can be happy at Oxford

- Offer a mix of online, in-person visits and residential opportunities for teachers to meet and hear personal experiences from undergraduates, tutors and academics with shared social identities and educational backgrounds, to increase the belief that people “like me” can both access and thrive at the university.

Providing sustained outreach programmes, through which long-term relationships are established, could be transformational for many state schoolteachers’ professional development and the support they offer their students to apply to the university.

Supporting state schoolteachers to feel better equipped with the knowledge and increased confidence needed to support student progression to selective universities such as Oxford, such programmes could make a significant contribution to increasing access to the most underrepresented groups at the university and in turn social mobility.