Students in marginalised groups undoubtedly face an abundance of challenges, not only with their academia, but also with feelings of belonging – which are central to both wellbeing and representation.

At the University of Nottingham Students’ Union, we’ve recently updated our strategy to prioritise equity as one of our key values. We recognise that different marginalised cohorts have different needs and require tailored adjustments to bring their best selves to their studies, and everything that comes with this.

Therefore, at the start of 2020, research was commissioned by our SU to explore themes of discrimination, representation, and wellbeing, and how this perpetuates the disparity in our own marginalised student experience.

Most importantly, our aim with this research was to centre the voices of marginalised students so that these individuals can guide our value of equity. So, we took two steps back and asked ourselves the basics: who are our students, what are their experiences, and what do they need from us?

Our new piece of research, titled “I just feel really misunderstood”: a qualitative study into EDI and marginalised groups’, sought to set a precedent that all universities and unions should take the necessary steps to understand their own marginalised student communities.

It is not enough that we take an outward-looking, sector-focussed approach to equality, diversity, and inclusion when we are dealing with such heterogeneous landscapes, cohorts, and individuals. Instead, we should use those national trends and statistics to set foundations for work that are first explored on an institutional-level, and then applied more specifically.

This allows for the conceptualisation of vital measures and ideas as well as ensuring that further research and the support available to these populations is relevant, effective and well informed (by the voices that should matter the most, students’).

Misunderstanding marginalisation

From initiating discussion, we soon saw that specific and tailored support packages were vital in ensuring the wellbeing, representation and belonging of our marginalised students. Belonging itself was understood as feeling welcomed and valued by others in a community, as well as being provided with fair and equitable opportunities.

In other words, it concerned how the environment and others within said environment catered to their needs – and where needs were not met, students ultimately felt misunderstood and overlooked.

Representation was integral to ensuring feelings of belonging, specifically, being able to recognise others in the staff and student populations who share their personal characteristics (e.g. race, gender or sexuality).

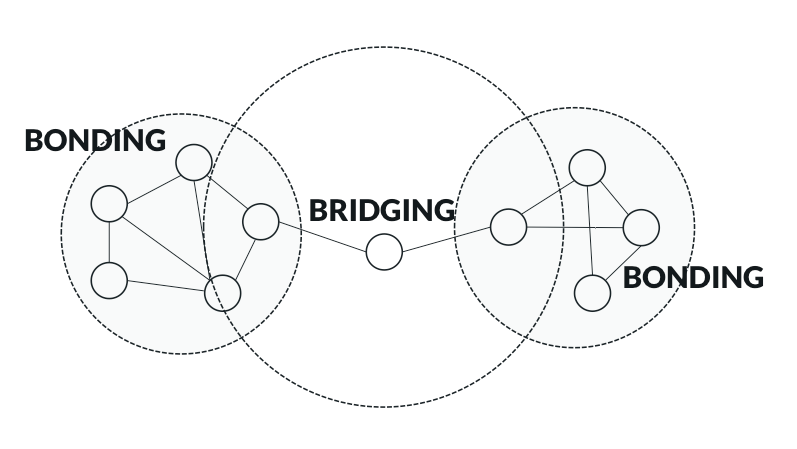

Yet, especially for international and BAME communities, our students told us that they felt unrepresented and without role models – which was exacerbated where identities were intersectional. As in Social Capital theory, forming bonding relationships with those who are similar to us is important. And where these social bonds are formed, for our marginalised students, it provided a community that inherently understood their needs and experiences.

Should we be prioritising identity or interest?

Identity-based student groups are a great example of how these communities can be established, and where most effective, they help students to feel at home and accepted for who they are. Not only does this ease feelings of being homesick but supports wellbeing more generally. However, instances of intra-minority discrimination (specifically microaggressions) appear to threaten the safety and belonging felt in groups such as these.

A few students across groups, especially intersectional or mixed-race students, recalled having their identity dismissed or denied by those in that same group, as they didn’t look, sound or act how they were expected to. As a result of this, marginalised students sometimes found it difficult to find a space in which they belong, and often missed out on opportunities to form those vital bonding relationships.

While experiences with identity groups evidenced the importance of ensuring solid relationships between those who share protected characteristics, it was not imperative for all students to engage with or be supported by others in this way. Those who valued interest-based groups found that relationships formed more organically, there was a lessened pressure on their identity, and it even allowed international students to integrate more fully into the British culture.

Students use bridging relationships (with people who are unalike in personal characteristics) to create feelings of belonging and community just as effectively as through bonding relationships – also outlined in Social Capital theory. Ultimately, underrepresented students at the University of Nottingham use different groups to facilitate belonging in ways that are most tailored to their needs.

Exploring the experience of marginalised students in this way has allowed us to understand the multifaceted nature of belonging. When thinking about bonding relationships and how they facilitate belonging, representation is central, yet for bridging relationships, being understood by those who do not share protected characteristics is most important.

In addition, what students value with regards to a sense of belonging varies within and between marginalised groups, and so engagement type cannot be solely determined by protected characteristic. It, therefore, seems only appropriate that our efforts within the students’ union reflect this.

By working in a way that is individualistic, non-assumptive and flexible means that we prioritise the underlying motivations of our members’ engagement and its relationship with belonging, rather than misunderstanding them.

What’s next for the sector?

These social relationships clearly play a vital part in the self-management of mental health and wellbeing for underrepresented students. So, what does this mean for universities and students’ unions that are currently bound by government guidelines surrounding coronavirus, and for those students currently self-isolating or unwilling to attend group events either online or otherwise?

As a sector, we anticipate an increase in loneliness and a decline in belonging where normal social activity is limited. But how do we support and facilitate those essential relationships, if we are to remain at a two-metre distance indefinitely?

One thing this research can offer is that, for our marginalised students, trust played a large part in the effectiveness of support – specifically, aiding the access of reporting services, mental health support and other professional services.

Exploring trust further helped to identify four core components in establishing a good level of trust. With “understanding” featuring strongly here (alongside approachability, professionalism, and expertise), it again calls for institutions to ask those basic questions – who are your students, what are their experiences, and what do they need of you?

While simply being aware of these issues is not a fix, research such as this begins to broaden our understanding of how we can most effectively support and ensure justice for underrepresented students – which we must be brave and ambitious in working towards. Work must be collaborative and non-assumptive in approach, as to not further misunderstand marginalisation.