Throughout the pandemic, both governments and regulators have placed a significant emphasis on complaints as a way for students to resolve issues relating to their provision and in answer to calls for “refunds”.

Universities Minister Michelle Donelan has repeatedly insisted that students in England can avail themselves of the Office of the Independent Adjudicator (OIAHE) even where the nature of a student complaint could make it ineligible for consideration under the scheme.

Partly in response to demand from students and the impact of the pandemic, OIAHE is even consulting on the introduction of a group complaints process for students – and the government noted its proposed process in its response to the Petitions Committee’s report on the impact of Covid-19 on university students.

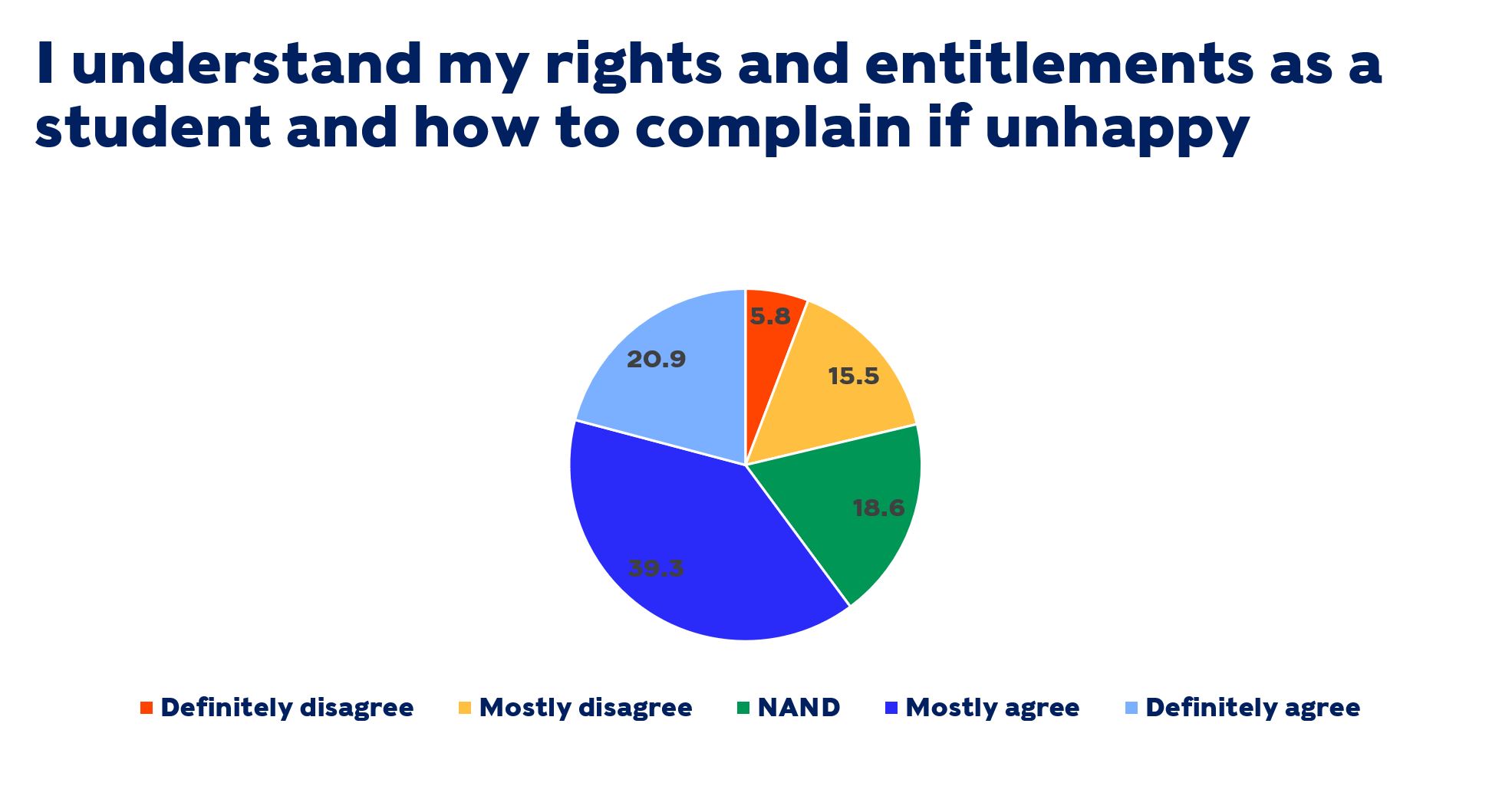

Polling numbers

Given the emphasis on complaints, in our polling on non-continuation we wanted to know if students understand their rights and entitlements and how to complain – so we tacked a question onto the end of our polling on non-continuation and social learning. The results suggest a significant level of uncertainty amongst students:

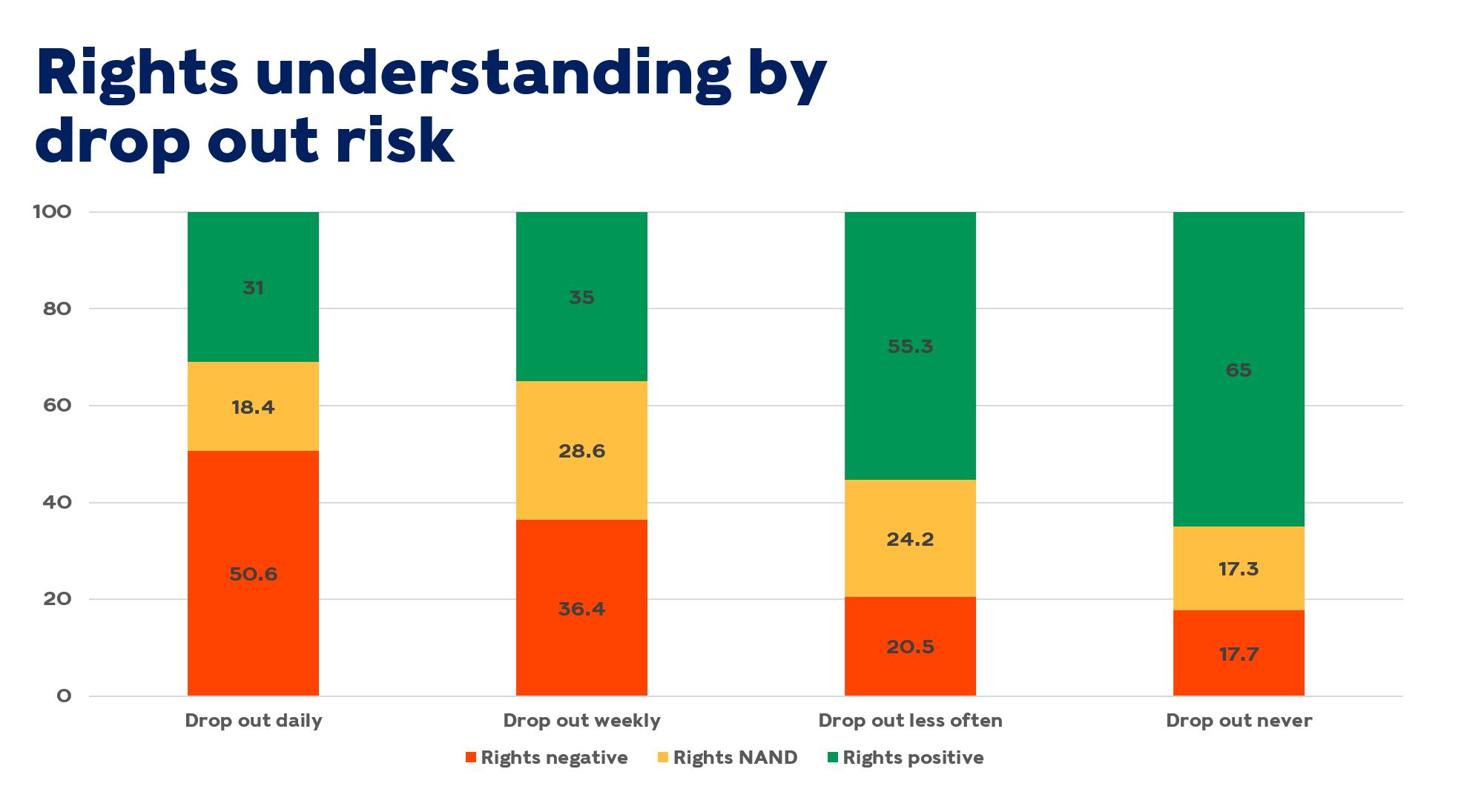

Concerningly, students “at risk” of dropping out (ie thinking about it on a daily or weekly basis) were more likely to say they were not clear about their rights and entitlements:

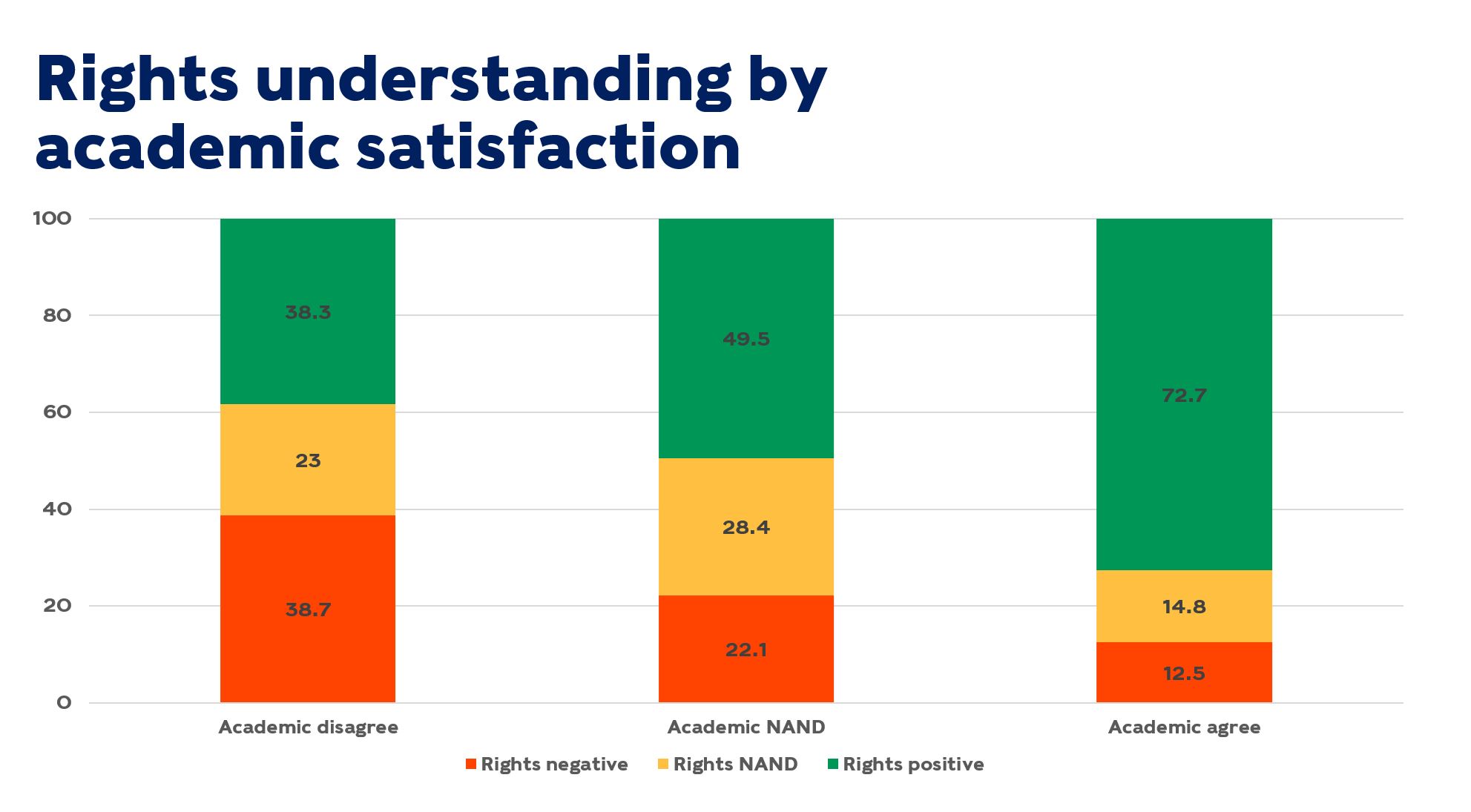

And students that were not academically satisfied were significantly less likely to be aware of their rights and entitlements and how to complain – a real challenge to the stated way that students are to resolve those issues:

What are students saying

In the qualitative feedback we explored student perceptions in this area of rights and entitlements.

Five familiar themes emerged. A large number of students say that they do not understand their rights. Many worry that complaining would not achieve anything or that it would harm their academic career. And many either do not understand the basis on which they might make a complaint, or trust that it would achieve anything:

- It’s the government and sages fault so who do I complain to?

- They don’t advertise the right to complain. If I do try, corruption would get in the way.

- I have never sought help as it does not feel accessible to me

- I know that whatever I complain about or am upset by something, I will be told exactly and in great detail how hard everyone is trying

- The union helped me get my supervisor changed last year

- I don’t know if this is the best they can do or what I should expect

- I wasn’t informed much about student rights

- I have already complained and it was a waste of 10 weeks of my life. I won’t ever attempt to put in a complaint again.

- I have no idea. I honestly feel like I’m getting ripped off

- Because I don’t want to create bias with module leaders because of complaining

- Tutors never respond to emails and if they do they essentially kindly tell you to get stuffed

The sense of powerlessness comes through strongly:

- I don’t really have any rights

- There has been no information about how to complain about student satisfaction

- Because I don’t actually know/know what it would achieve.

- Because the uni just respond with ‘we didn’t ask for covid so it’s not our fault’,

- Because our complaints never do anything. The university never changes, they ignore petitions etc

- The student union reps have helped us a lot with the XXXXXXXX

- I don’t know how to complain and tbh it is pointless complaining, uni will just say unprecedented

- I got one call from a lady from the uni asking if i was okay and that was the end of the call

- The university SU has informed people about the help they can provide if you are not happy

- I feel like I’m being given conflicting information all the time about who to contact.

What are they complaining about?

In the qualitative questions in our polling we asked why students might be dissatisfied with their experience so far this term, and a number of themes emerged. A notable proportion of negative responses focussed on access issues:

- As a dyslexic student, studying online is not an ideal solution to me building and learning skills

- 2 hours per week in my career path and its online learning with a terrible connection.

- 100% online teaching has been highly ineffective and hard to follow.

- Because half of my lectures are cut out because of my wifi or the lectures wifi

- Daily tech difficulties within lectures, lack of tech support by the uni, no access to library

- Everything is online which is difficult for people who do not have stable Wi-fi/ who can’t afford it

A large number were unhappy with what they saw as value for money or expectation v delivery issues:

- Because everything is online and we were not told until the semester began

- all my classes are online, i am never on campus. we were lied to before getting here saying we’d have classes on campus

- All tutorials are online, no point returning to campus

- Why did I move here to learn on a laptop

- Lied to by my university about classes being in person. Moved to the UK for no reason.

Several comments focused on facilities, or the mix between theory and practical activity – and suggest the sector has a looming issue with practical courses and the availability of advertised placements and work experience opportunities:

- Covid made it harder to gain access to facilities

- I can’t get into the studio at all

- We are not allowed to spend time in the Library

- STUDYING PERFORMING ARTS IS A REAL STRUGGLE IN THOSE TIMES

- Because when I picked psychology it was because I wanted to “do” psychology, not learn about it through videos

- Covid is making it difficult to enter the lab and social distancing is making training difficult

- My course is supposed to be very practical but, because of COVID, we only have one practical lesson a week.

- I am disappointed that practicals have been cancelled due to moving to tier 3. Why?

A number of negative comments related to organisation and management issues:

- 11 days before placement starts and we still don’t know where will will be allocated

- The timetable hasn’t been right for any of the weeks yet

- 2 hour lectures are being squeezed into 45 minutes due to seminar groups having to be split to allow

- Not enough communication about my course too much about the university and not breaking the rules

And many were dissatisfied with what we might call the volume of teaching:

- 20 minute contact time with my lecturer is not enough

- All lectures have been online so my learning has been stunted and challenged. I have also been staring at a screen for too long.

- Lots of un-engaging video content, some lectures have decided to simply not run live seminars.

- Low contact hours, lots of time by myself in my room listening to lectures and seminars

- No in class learning, pre recorded lectures from last year, no additional help

- Online teaching is inadequate, blackboars collab barely works, work isn’t uploaded soon enough

- Expected live lectures and more online interactivity with lecturers and coursemates outside not just videos

- Have had no time in person, only one module records online lectures, other modules just provide notes

OIA, DfE and OfS all stress that students should raise concerns early to get a response. But if those concerns are not resolved, can they complain – and is it reasonable to do so, especially during a pandemic?

What could be done?

First, we ought to work to get our stories straight over the types of things students might complain about. On the issue of refunds, recently Russel Group Chair and Manchester VC Nancy Rothwell said:

There is a regulatory body in England that advises us on this, and in fact can enforce it. They look at: Did the student get the outcomes they needed? Did they get the degree they needed, the qualification they needed, the experience they needed and the skills they needed? They don’t ask how many lectures did they get, or how much was online or how much was face-to-face. They focus on the outcome and that outcome, obviously, we can’t tell until the end of the academic year.”

That suggests that in consumer law all that matters are the outcomes – and that the quantum of teaching, how it’s delivered or the wider “experience” that students get would not be relevant. But do the regulators agree in the way suggested?

Much of the qualitative feedback about low satisfaction with the academic experience in our polling, for example, seems to fit this wider bill from OIAHE:

It’s obviously important for students who are making decisions – decisions that are likely to affect the rest of their lives – to know what they are committing themselves to and what they can expect, and it is equally important for providers not to overpromise. Another spike in UK-wide or local coronavirus infections could derail the best of plans.

Students may be happy to sign up to a term of online learning, but a full year may not be so palatable. Others may have chosen a course because of face-to-face elements that might have to be abandoned if there is another lockdown.

Language students may see their crucial year abroad evaporate. Work placements may be lost, shortened or postponed. Access to labs, design and art spaces, performance opportunities and professional placements may all be reduced.

What students who are going into their first year, with their eyes open, decide to accept might not work for re-enrolling students whose expectations are based on what they were promised when they signed up in a different age. And postgraduate and PhD students are likely to face some distinct challenges.

And even if we set aside this question about aspects of the wider student experience, OfS seems to disagree with the Rothwell line:

Sufficient information needs to be given to prospective students about the course, in line with CMA guidance, including information about any planned changes and the provider’s plans for different scenarios. Providers must set out information that includes the following:

How the course will be delivered. This includes the extent to which the course will now be delivered online rather than face-to-face and how the balance between, lectures, seminars and self-learning has changed. Prospective students will be particularly interested in the volume and arrangements of contact hours and support and resources for leaming if this is now taking place online and virtually.

There’s no doubt that lots of providers are right now gathering feedback from students on what they are experiencing with a view to learning from it for January. But in some cases the things students are saying move from “useful feedback for the future” to “being treated unacceptably”. But do we know where that line is? And if we don’t, do students?

We surely need to address, urgently, what students can complain about. And to that end we need to know what students can legally expect – both in and out of a pandemic.

Righting the wrongs

I’ve argued for some time that we have a problem with student “rights”. Models of partnership, mixed with more subtle models of treating students like children still at school, both ensure that students may well not understand what they should expect and what they could do about it if they are somehow let down.

I’ve also noted before that it is possible to operate environments where lay “users” partner with experts over their outcomes, but the power imbalances involved mean that specific strategies are deployed to support users to understand their rights and support users with complaints if things go wrong – in health.

Part of the difficulty in higher education is that there is a reluctance to address the issue of the rights that students have because much of the development work in this area in recent years has been around students’ consumer rights.

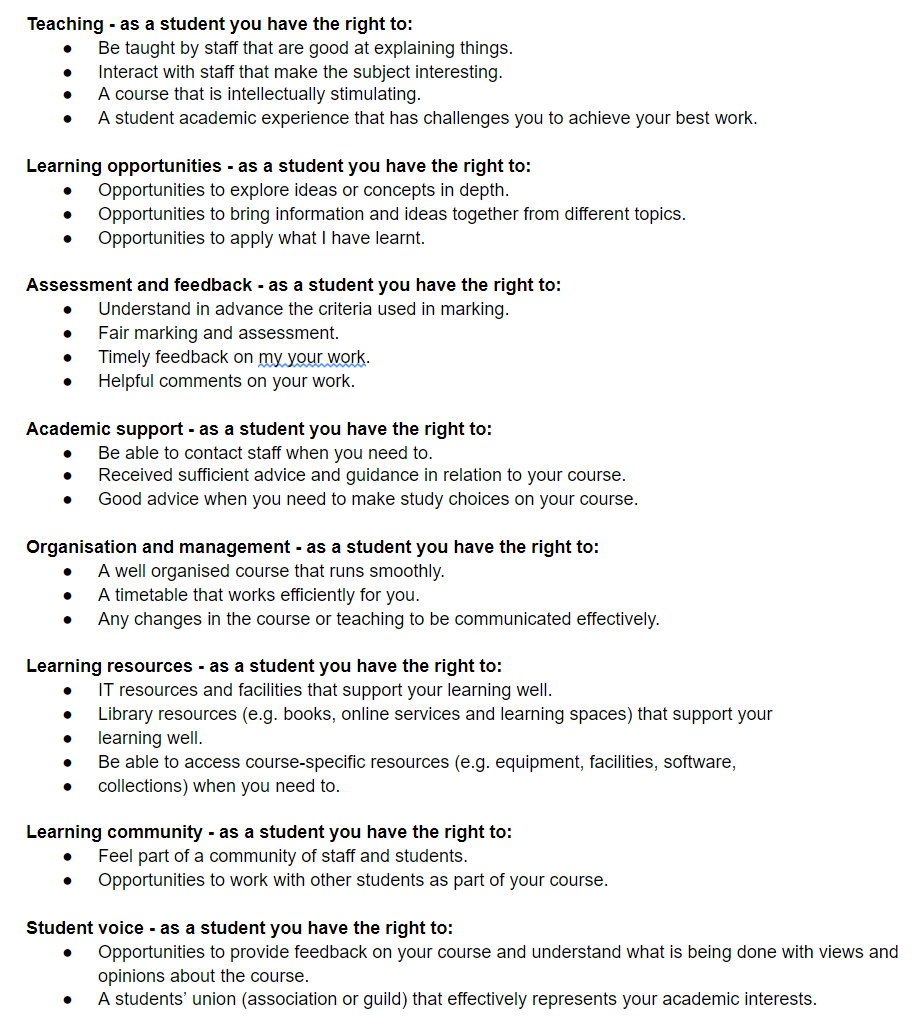

But take for example the National Student Survey. The survey’s questions are effectively a national consensus statement on the sort of thing a student should be able to expect as a right. Whatever we think about the NSS review, it is odd that we ask students at the end about things we never tell them they ought to be able to expect at the start. Can anyone think of anything wrong with expressing the questions as universal sector wide rights at the start of the course?

We could display it everywhere. We could ask courses/providers to explain to students “here’s how we do each of these”. It would mean students understood the grounds upon which they could base a complaint, not just the process. And it would mean that we maximise the chances of students being more assertive about their way in which their educational partnership should work early on.

I’ve also talked before about the important role that patient support to make complaints plays in the health service, and the opportunity we have to assure and improve the standard of practice in this area in students’ unions. Given the asymmetries we should want all students to be able to access support here.

What’s clear is that our polling shows that a significant proportion of students are not happy about their provision this year and feel powerless to do anything about it. The mistake is to assume that students understanding their rights would be unhelpful or oppositional. OfS’ forthcoming “website resources for students on their rights during the pandemic” can’t come soon enough. It might just ensure that students raise their concerns early enough for us to address them.

Download the main results of the Don’t Drop Out survey.

We are particularly grateful to the students’ unions that made the work happen with us – big thanks to the SUs at Middlesex University, Queen Mary, University of London, Kingston University, University of Southampton, University of Sunderland, City University of London, University of Leicester, Bath Spa University, University of Bedfordshire, UEA, Bangor University, University of Manchester, UCLAN, Coventry University, Leeds Beckett University, University of Worcester, King’s College London, UCL, UEL, Canterbury Christ Church, UCB, St Marys University, Twickenham, Oxford Brookes University, Solent University, Southampton, University of Plymouth, University of Sheffield, University of Nottingham, and University of the Arts London.

Trendence is a leading student-focused market research firm in the UK and Ireland.

“Students considering dropping out are also significantly less likely to complain – with students citing a lack of understanding about their rights, a fear of reprisals in assessment,” Actually many Academic’s are scared to the point of breakdown that NSS poor scores, through student reprisal, through no fault of their own, will be used to prevent pay grade uplifts at appraisal, block promotion or even to enable dismissal through under performance procedures, those that are not ‘compliant’ and easy to ‘manage’ especially so.

Jim, I recall as a keen young university administrator publishing an article in an education journal in 1992. Spurred on by my experience working with the late Frank Mattison at Hull from 1981-6 and later on co-authoring the CUA/CRS (now AUA/AHUA) book on universities and the law (1990). It was about the concept of a university student contract. The CVCP (now UUK), the HEQC (now QAA) and others showed some interest. Later I developed the contents of such a document, from 1994 onwards to the latest ©️version (with David Palfreyman) soon to be included in the 2020/2021 edition of The… Read more »