Speak to anyone that was involved in Welcome Week festivities this September and October, and they’ll tell you that students seem to be bouncing back.

Attendance at freshers fairs and meet and greets was up; volunteering for reps and committees seems to be increasing; even anecdotal evaluations of attendance at classes seem to use words like “buoyant”.

Let’s hope so, if it’s true let’s hope it lasts, and let’s also hope that some post-Covid return to “normality” isn’t masking a wider problem for those not manifesting in person.

There’s been a lot of student mental health research around – barely a week seems to pass without another survey from one firm or another suggesting that buying their thing will improve students’ wellbeing – but one of the better and more authoritative ones to emerge in recent years comes from Cibyl (part of Group GTI) in partnership with Accenture and Student Minds.

Its Student Mental Health Study 2024 – fieldwork October 2023 to February 2024, with a sample size of 12,644 (and weighted for gender and university) – paints a pretty bleak picture:

- The proportion of respondents regularly worrying about their mental health has remained consistently high over the past four years – three-quarters of those surveyed – and two-thirds of respondents across all age groups reported worrying about money daily or weekly in the last year.

- There’s been a decrease in the percentage who report never having experienced mental health difficulties – that’s dropped from 23 per cent in 2023 to 14 per cent in 2024.

- The proportion of undergraduates reporting a decline in their mental health since starting university has been steadily rising – nearly half this year, up from 40 per cent in 2021.

- Increasing numbers of students are reporting no knowledge of mental health services – down at 7 per cent in 2021, and up at 25 per cent now – although there’s a rising trend of first-year undergraduates considering mental health provision when choosing their university. This year, three in five prioritised mental health support, up from 39 per cent in 2021.

- And non-binary, LGBTQ+ and students from low socio-economic backgrounds continue to report the lowest mental health scores.

The state they’re in

In Cibyl’s sample, nearly half (46 per cent) of first-year students had some kind of mental health diagnosis prior to starting university, with 11 per cent receiving their diagnosis during their first year. That’s an increase from the previous year – where 42 per cent had a pre-university diagnosis.

15 per cent of first years reported having a mental health disability, rising to 21 per cent when considering all survey participants. And there’s been an increase in the number of individuals with MH conditions who had either applied for or received Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA) – 11 per cent in 2024. ADHD diagnoses have also risen – also 11 per cent in 2024.

Nearly half of all respondents report that they’ve never taken time off for mental health reasons – compared to only 33 per cent for those with a low mental health score, and 18 per cent of those with a diagnosed mental health condition.

Disability reporting varies by ethnicity – 80 per cent of Black and 76 per cent of Asian respondents reported no known disability, higher than the overall average of 62 per cent. Among Black and Asian students, 9 per cent and 11 per cent reported MH difficulties, below the mean of 21 per cent.

This is why in England, OfS’ Access and Participation plan guidance told providers to take steps to increase disclosure and take steps to improve all students’ mental health – we’ll see soon how well it’s been holding providers to those commitments.

Notably, 1 in 6 respondents with a mental health (MH) condition identified it as a disability, and 1 in 9 of those with an MH condition applied for or received Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA). Even then, accessing DSA often proved challenging for some, causing delays in transport, missing social events, and lacking additional academic support. Feelings of inadequacy and being unworthy of formal disability support they may be entitled to came up a lot here. Delays like this won’t be helping.

Nearly 2 in 5 respondents with MH or other disabilities felt that their university was supportive of their mental wellbeing, though about 3 in 10 with MH disabilities and 1 in 5 with other disabilities disagreed, compared to a smaller 16 per cent disagreement rate among students without disabilities. And perceptions of university leaders’ care for mental and emotional wellbeing varied, with respondents with disabilities more likely to disagree than those without.

Suicide and self-harm

According to PAPYRUS, suicide is the leading cause of death for people aged 35 and under in the UK – and via some careful anonymity commitments, 90 per cent of respondents chose to answer questions on suicide and self-harm.

In this sample over 2 in 5 respondents (42 per cent) had experienced suicidal thoughts or feelings, and among those, 67 per cent had not acted on them, 14 per cent had made a plan, and 15 per cent had attempted suicide. 14 per cent reported experiencing suicidal thoughts for the first time at university. The need to revisit the guidance that’s appeared on the subject has never been greater – and strengthens the case for mandatory standards in this area (via the often poorly understood “duty of care” debate).

This year’s survey also included a question on self-harm for the first time, with 32 per cent of respondents admitting to having thought about self-harm. Nearly half who considered self-harm had acted on these thoughts, with 83 per cent beginning to self-harm before university, and 15 per cent starting at university. It very much strengthens the case for on-entry health screening – discussed on the site here.

Self-care?

In terms of coping, one of the more poorly understood phenomena is the extent to which factors can prevent students from deploying the sort of self-care strategies often pushed at them in the name of prevention.

In the sample, both students and graduates manage mental health challenges during stressful times by listening to music, prioritising sleep, exercising, and mindfulness – only 3 per cent say they use no strategy at all. But barriers like social anxiety, heavy workloads, physical illness, social stigma, and financial constraints all blunt those tools – and over 2 in 5 cite finances as a barrier.

Formal university wellbeing services remain important – but over half (55 per cent) of respondents reported not using any services for mental health concerns. Increasingly, both students and graduates are turning to other forms of support and personal strategies to manage mental health – 29 per cent access NHS/HSE or private counselling, and 38 per cent report using IAPT (talking therapies).

More concerning is the finding that nearly 1 in 5 respondents have turned to hospital A&E, suggesting barriers to accessing GP care or crises severe enough to warrant emergency intervention. Respondents cited feelings of embarrassment, doubt about the efficacy of university services, and challenges articulating their issues as reasons for not using available resources – and over 1 in 10 reported difficulty securing appointments as a barrier.

Characteristics

The characteristics make up – of a cohort, a class or even a provider – of course influences things. Students with low mental health (MH) scores report higher levels of concern about social issues like the economy, healthcare, and mental health than their peers, and also feel less prepared for university life.

Non-binary students, half of whom have low MH scores, exhibit significant worry about their future. Financial stress is particularly impactful for students from low socio-economic (SE) backgrounds, affecting their career aspirations, readiness for independent living, and preparation for academic life – over 7 in 10 of all respondents attributed some of their MH struggles to the cost-of-living crisis.

This, argues the report, creates a downward cycle where financial concerns lower MH scores, which in turn fuels more anxiety. Students from low SE backgrounds are also more likely to report MH difficulties (33 per cent vs. 26 per cent in high SE backgrounds) and unseen disabilities or health conditions (13 per cent vs. 7 per cent).

LGBTQ+ students, particularly non-binary respondents, show the highest rates of MH difficulties (40 per cent and 61 per cent respectively) compared to the average of 21 per cent.

Transition

Some 45 per cent of first-year undergraduates found the transition to university challenging, up from 34 per cent in 2023 – two-thirds felt prepared for independent living, and age influenced perceptions of readiness – over-25 first-year students were the most likely to feel prepared. The UK has pretty much the youngest starters and the youngest graduates in the OECD – it might be good for the labour market, but it increasingly looks like it’s bad for their health.

What helps with the transition? 60 per cent of students said that more help with meeting people and making friends would have eased their transition, with this sentiment stronger among school leavers than those over 25. Student tutoring – of the sort we’ve seen in Finland – has never looked more essential.

Nearly half of respondents indicated that financial support would have also helped, and for international students, more assistance with student visas would have been beneficial. Interestingly, 12 per cent of respondents felt that access to familiar food from their country or culture would have eased their adjustment – jobsworth attitudes to food safety in the face of international groups attempting to offer this sort of thing spring instantly to mind.

This year Cibyl also asked students whether their eating habits had changed since attending universities. Nearly two in five said they were eating unhealthier food – and those with unhealthy eating habits are more likely to have a low mental health score and social anxiety, nor use coping strategies.

Having a takeaway or some sugary snacks a few times a month isn’t an instant red flag, but food itself can be a source of anxiety for many and unhealthy eating may signal something more serious, according to a report from The Food Foundation. Couple this with the fact that it is increasingly expensive to meet the cost of the government recommended healthy diet and growing numbers of students experiencing food insecurity – neither is a recipe for positive student wellbeing.

Back to belonging

We’ve banged on a lot about belonging here on the site in recent years – here, when asked about concerns over making friends during the year, 34 per cent worried daily or weekly. Social anxiety is a major obstacle – 53 per cent said it prevented them from using strategies to stay mentally healthy, up at 64 per cent of those with low mental health scores – another causation/correlation cycle. 17 per cent reported having no friends at university.

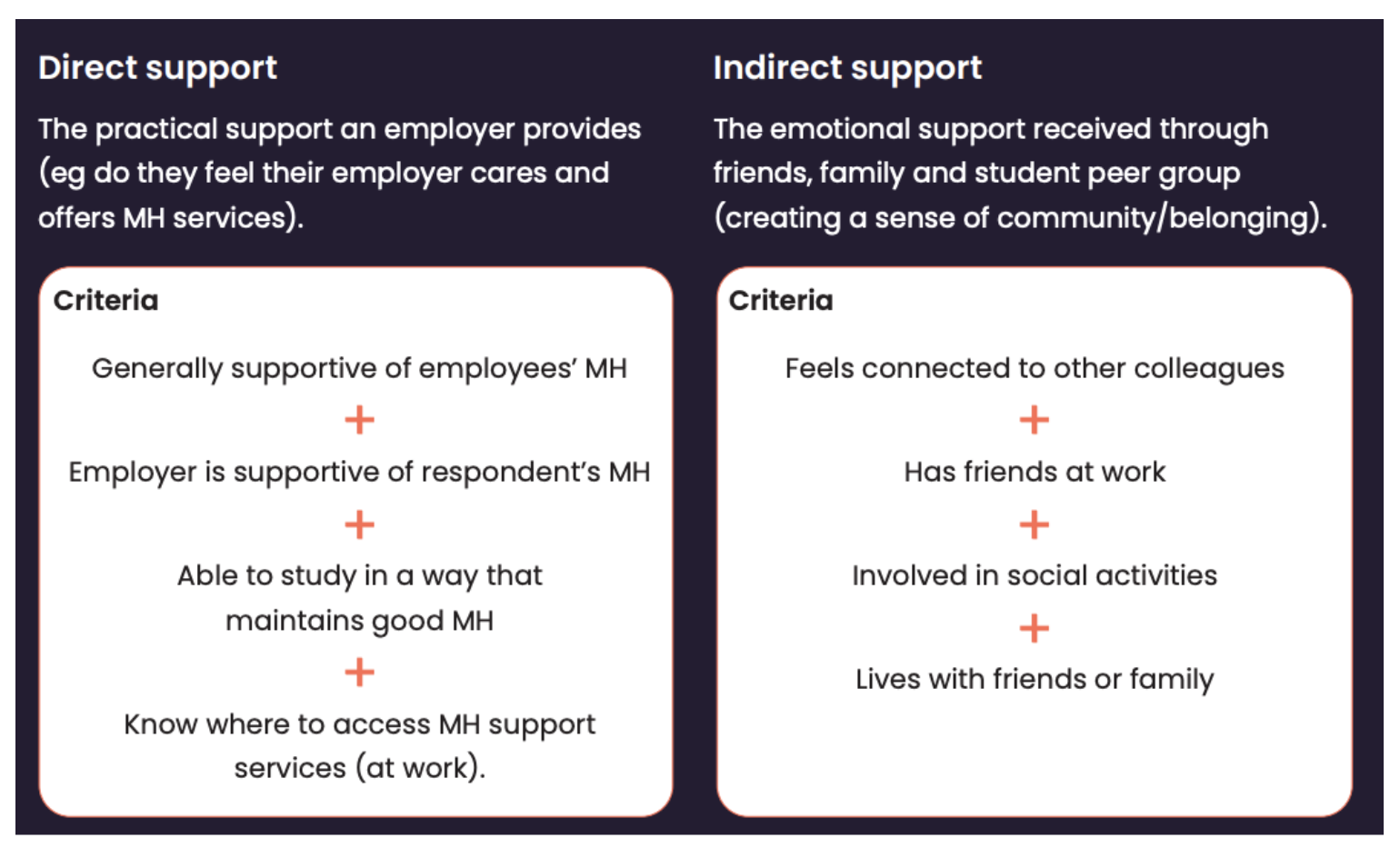

What emerges from it all is a fairly simple model – an approach that balances direct and indirect support and emphasises community building. Direct support like a compassionate climate, availability of services, flexibility in the curriculum and explicit information on how to find resources is all in there – but indirect support – learning how to emotionally feel support through social connections and a sense of belonging – is just as important.

Creating an environment where students feel emotionally “safe” is not only an increasingly contested concept in the media and across the culture wars, but one that’s harder and harder for students to realise – as opportunities to connect, develop friendships, integrate, and engage socially get squeezed by economic and health hurdles.

But notwithstanding the old correlation/causation concerns, the stats don’t lie – and reflect that finding of ours in another Cibyl survey that those with friends on their course feel more satisfied with support from the university.

What’s becoming really clear is that taking existing opportunities for connection – student clubs, “reslife” activity or even seminar attendance, and making them a bit more friendly or adjusting the times they run at may have diminishing returns. Going right back to basics – and finding ways to cause students to establish, maintain and sustain friendships that blossom into communities – feels like a much better bet.

Is there data for Post Grad students? How does that compare, given that many/most Universities treat them as cheap staff labour without the protections?

I remain fascinated that there is very little discussion of the role/responsibly of the NHS and of schools when exploring these details…and indeed of wider concerns and causes that are out with the control/responsibility of universities. Tens of thousands of students are arriving in universities experiencing the impact of mental ill health and the focus seems to be solely on what universities (and their student unions/associations) need to do to respond. Is the same discussion being aired about schools and their responsibilities to support the healthy development of young people or am I missing this?