You’re transport secretary. It’s mid-morning on 1 January 2021, and your officials have just sent you a WhatsApp message of great news to get up on social media as soon as possible.

You read it, get a rush of excitement, grab your phone, spend longer than you should finding the mortarboard emoji, and then you copy and paste the following into your Twitter app:

STUDENT TRAVEL UPDATE 🎓:

Following the announcement of a phased return to campus, if you have already booked rail tickets to travel back to university, you can now re-book wherever you bought the ticket WITHOUT paying admin fees.

— Rt Hon Grant Shapps MP (@grantshapps) January 1, 2021

Yes Grant, but when? When should I rebook it for? Even if we ignore that they’ll still have to pay the difference in the actual fare, students can’t let the date on the original ticket pass and then rebook it – they’ll have to rebook it now.

I’m no Nostradamus, and having done the usual re-read and re-tweet of my output this year over the break, I’m also pretty confident that I haven’t been over-relying on the retro-specto-scope. So why can I see these things, but our dear leaders can’t?

Rounding the coroner

If there’s one thing that has characterised the leadership that’s been on offer during the pandemic, it’s been premature optimism – that the whole thing will be over sooner than it has been in reality. See you after Easter. There’ll be (student and spectator) sport in September. Eat out to help out. Christmas. That sort of thing.

When you couple that with a reluctance to act until the last minute – after all, it might not end up as bad as you fear – you get disruption. Constant, grinding, exhausting disruption.

It’s disruption that starts with intense meetings about the emergency online pivot. It’s disruption that continues all summer with unrealistic working groups about teaching spaces and timetabling and something someone called “hyflex”. It’s overlaid with a belief that messages of gratitude, optimism and guidance compliance will ensure you end up in The Good Place.

It’s disruption that hits students in access and participation categories hardest, and makes the already precarious situation facing parents or those with wider employment or caring commitments throw their hands in the air with frustration.

It’s disruption that peaks with the grotesque chaos of a university – a university! – pretending it’s not disruption at all – telling its own students, in pursuit of academic standards, that the pandemic doesn’t count as an extenuating circumstance because its impacts this term have been predictable. While not delivering most of what was promised “in person” because the pandemic has been so… unpredictable.

It’s the unending, relentless, maddening disruption of it all – never giving ourselves the time to breathe, or plan, or think through the implications – glued to the rank futility of doing the same thing over and over again while expecting a different result.

Viral spread

Do you remember that story that went viral in August 2019 about the undergraduate from Durham who claimed to have written her 12,000 word dissertation in eight hours – and still got a 2:1?

Philosophy graduate Imogen Noble told The Tab:

I knew based off of other essays I can bang out a few thousand words in a couple of hours so I rested hard on my laurels.

At the time, HuffPo’s Executive Editor Jess Brammar had a theory about the popularity of the story. The “essay crisis” is an overused phrase in British journalism and politics that is used to describe leaving things to the last minute. Brammar argues that it is a niche experience, used as a casual linguistic form of elitism – and when David Cameron became known as the “essay crisis prime minister”, Brammar reminded us that the New Statesman framed the description as:

…a gibe that must have seemed meaningless to millions of people who never experienced the weekly rhythms of the Oxford tutorial system.

Our tendency to see the world through these optics infects our society generally and its understanding of higher education deeply. It’s one of the reasons why many believe that “too many people” are at university – because there just can’t be that many special geniuses around. University isn’t for ordinary people, grafting their way towards a qualification. It’s for the special ones. Depending on the author, they mean people like… “us”.

A refund? On your tuition fees? You should jolly well feel lucky to be here. You’re special. You got in.

It all imagines that success can be achieved through a mysterious, eccentric, just-in-time meritocratic brilliance – rather than those stories merely acting as evidence of a particular kind of privilege and confidence at a particular time in a particular type of subject in a particular kind of university. Without trying to hold down a part time job.

As Brammar points out:

There is also an arrogance to the belief that you can do something the night before that takes mere mortals weeks of work. And it’s based on a fundamental knowledge that things will be OK, regardless of your own failure to perform. Which, in many of these cases, is true. Privilege is a wonderful thing.

In the Guardian over Christmas, columnist Rafael Behr argued that this “essay crisis” thing was how Boris Johnson dealt with Brexit – imagining that brinkmanship was a negotiating strategy to wring concessions out of Brussels, but in reality just a way to simplify the decision by eliminating options that needed time to develop:

He lets procrastination do the heavy lifting. He can then tell himself (and his audience) that the final outcome, while not perfect, is the best available solution. And maybe it is. But only because it is so late in the day and all the better solutions have long since expired.

All of this is everywhere in our politics, and it runs deep in our big (boarding) school higher education policy. It was there at the start of the pandemic, there during the examnishambles and it’s there in the Christmas and New Year “plans”. It’s there in the repeated reluctance last term to accept that commuter students exist and the fanciful last minute notion of a student travel window. It’s there in that line in Michelle Donelan’s letter about a delay to the staggered return to campus in January where she (or her officials) talk about students “reading” a subject before asking international students to switch plane tickets with three days to go.

It’s not a great way to run a state, it looks awful as a way to run a university, and it’s starting to look like a catastrophic way to handle a pandemic. So what would happen if we did the opposite?

Another higher education sector is possible

On Andrew Marr at the weekend, Boris Johnson said:

It may be that we need to do things in the next few weeks that will be tougher in many parts of the country. I’m fully reconciled to that.

In our house, we were shouting at the telly words to the effect of “So lock down properly now then! Why does this government do everything two weeks too late?”

I accept that not everyone shares my view on this, but the thought experiment here is one where we try to do the opposite – go early, go hard, and back off if we can – what former No.10 Deputy Chief of Staff Gavin Kelly called at the weekend:

When the risks of (in)action are asymmetric then err on the side of swift, aggressive measures that can be unwound in the event they aren’t needed. Don’t play catch-up with something contagious (virus, bank runs). Never assume things can’t get worse.

So we first vow as a sector not to wait (again) for government guidance on higher education – principally because we don’t think it fully understands consequences or disruption on our staff and students, and repeatedly comes too late to be useful.

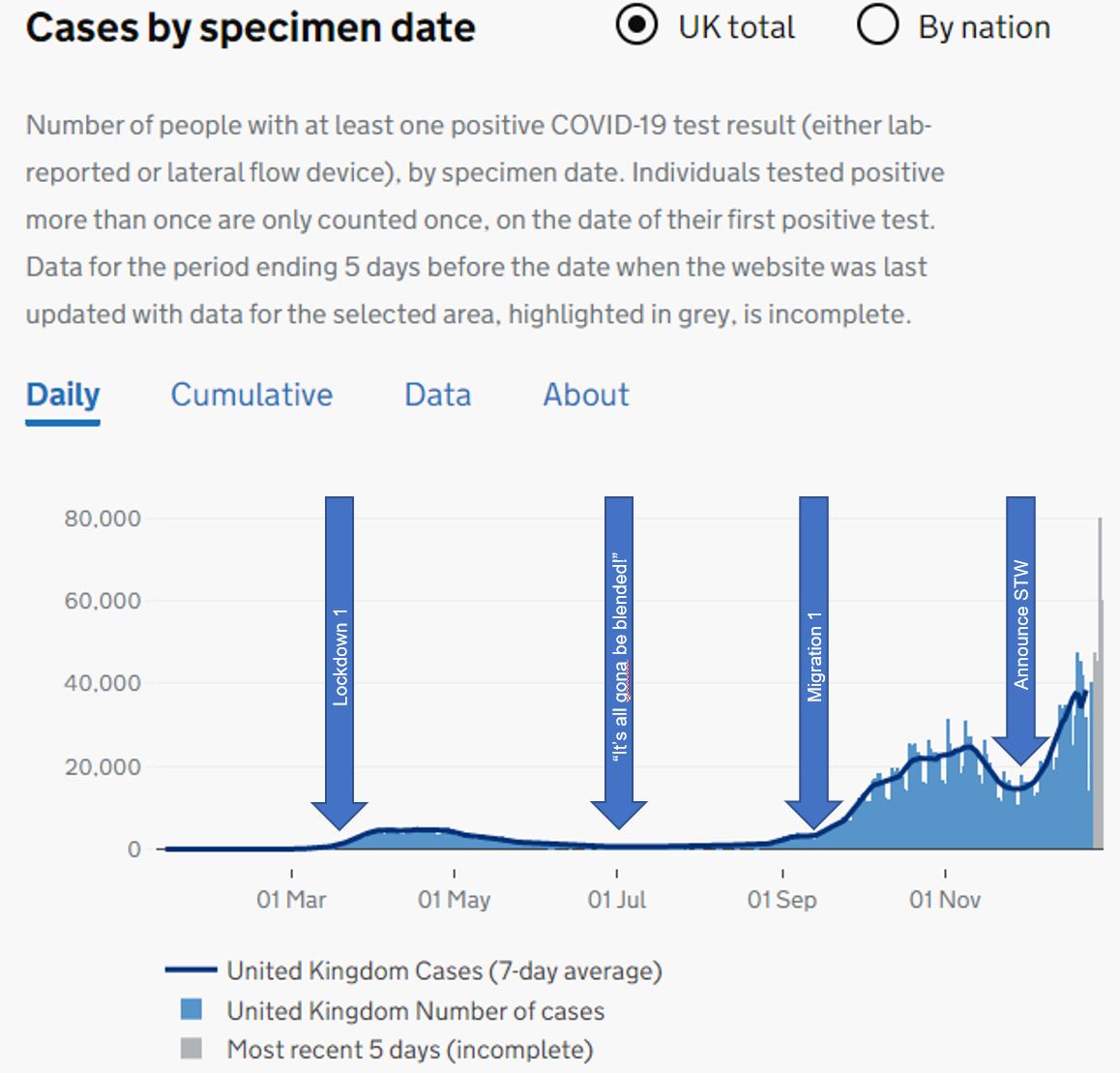

We look at infection rates, hospitalisation and the general progress of this “new strain”.

The UK’s Covid-19 curve is now almost vertical. pic.twitter.com/ZtRCJRDzwA

— George Eaton (@georgeeaton) January 3, 2021

We look at the SAGE paper on distancing and ventilation and realise that we’re about to reduce even further the “in person” we can offer because the two metre rule and ventilation protocols will have to change during the snow season. We remember the evidence about halls and isolation. We know social activity is off for the term, and we know another counsellor won’t cut it.

If we thought bringing students back to campus in September was touch and go, it certainly is now. Universities can’t deliver what was offered in July. The version that can be delivered might exacerbate the third wave. It would look terrible. Even the Westminster government has delayed the great migration for all but health courses. Return to campus is going to be delayed again.

Yes Grant, but when?

Then we look at the term. It ends for some universities in ten weeks’ time. We’ll likely have a fortnight of snow to deal with between now and then. And the government has set an expectation that universities will be expected to lateral flow test all students twice over five weeks, with the “all” now mandatory via data returns to OfS.

I’ve long argued universities are like theme parks. And people who run theme parks need to understand demand bulges, maths and throughput.

Take a university of say 25,000 taught programmes students (with about 3,000 staff). That’s 11,000 tests a week, or 1,600 tests a day over seven days, or 160 tests an hour if you run for ten hours a day. That looked nigh-on impossible before yesterday.

It’s probably one of the reasons why there’s been no formal announcement on regular testing throughout the term as yet. You might be able to screen “all” students, or you might be able to screen students who volunteer every couple of weeks, but it’s unlikely you can do both – and I guarantee not weekly, as Boris suggested for schools on Marr.

If a fictional 25,000 student university was lateral-flow testing all students and staff once a week we’d be looking at 358 tests an hour, ten hours a day, seven days a week, with no slot wastage. As if.

No right of readmission

But let’s go back to the “entry testing” problem. Lots of universities have small numbers in the now allowed-in-the-first-three-weeks category. Imagine my University of Fictionalchester has 20,000 in the “from last week of January” category. Assume that’s pushed back by a fortnight.

Let’s say I’m running my testing centre from 8am to 6pm seven days a week, and I can do 100 tests an hour. And remember everyone needs two tests. It’s still the best part of six weeks, which if I start in say a month’s time, would take some students’ return up to the end of March – with no regular screening factored in for those who’ve already arrived or been around in January.

If “away from home” students turn up at the “wrong time” in terms of availability of throughput capacity, they probably can’t be tested in a timely way. And then remember that mass lateral flow screening was envisaged as being useful at finding more positives than you would by just waiting for symptoms to emerge, and has never been authorised for use in making universities [or schools] “safe” by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

It’s not suitable for proving negatives to give people “passports”, there are major dangers from the false confidence it gives to people, we’ve never properly tested its efficacy in this format, we’ve certainly not considered whether the false confidence might be actively unhelpful given the new strain, and we’re having to consistently oversell its ability to deliver personal safety to generate collective participation.

It’s expensive. And it gobbles bandwidth, attention, and time and energy. It doesn’t sound like something the university sector ought to be involved with. So we stop doing it and we accept that the period between now and Easter and after it – for most taught students – is an in person write off.

The corkscrew will not operate today

Instead, we announce a new reality.

- For medics and nurses and vets (ironically some of the few students who in law aren’t consumers), we carry on as we were doing.

- For students who don’t “need” in-person teaching, we say now that it won’t happen all term and lay out a consistent pattern of teaching, support and assessment that will apply throughout the academic year.

- For those who do need in-person components, we commit to delivering them when it’s safe to do so at no cost. And we stop pretending that some F2F components aren’t necessary when many are for confidence as well as competence.

- For everyone, we make arrangements to extend the “taught” academic year by six weeks to help with vaccination, revise teaching and learning, arrange extra support for students who’s fallen behind, address the digital divide, and handle our assessment and learning detriment conundrums.

Next academic year will start four or so weeks later, giving time to run a sensible admissions round that picks through whatever chaos is left by decision making within schools policy. And we stay there in the future, to accommodate PQA.

Fair’s fair

And then the sector works with government on addressing the obvious, in-your-face truth. Wherever there are fees, you can’t sell students an on-campus experience, deny many of them access even to that town or city for three months and restrict access to the campus for the rest – all without warning them – and still collect full fees and rent for an online learning and teaching experience that you’re developing in real time. You just can’t.

It’s like going to Alton Towers on a Bank Holiday Monday. Do you expect it to be busy, restricting access to rides? Yes. But there’s a line – a limit over which letting people in full price without warning that queues could be running at four hours a ride is just bang out of order.

So address it you (the government and the sector) do five major things.

Some students will want to return to or stay in their “away from home” student accommodation, and that’s their choice. But no forcing. So first you change the law and allow any student anywhere to extract themselves from a rental accommodation contract backdated to the start of the student travel window in December. It’s nothing in comparison to the eye-watering yields that landlords make out of subsidised student loans, and you compensate universities for the lost income – ordering them to wean themselves off profiting from it over the next five years in return.

Second, you throw money at the digital divide – both capital in equipment loans and good connectivity – because you should be doing so every year. No student in the UK should be without the tech needed to study remotely.

Third, you make a commitment – that not a single student who faces additional costs because of the pandemic and the extension to the academic year will be out of pocket. The alternative is they drop out – so this is an excellent investment in human capacity and skills. And yes, you do the money thing and the academic year thing for your PGR students too.

Fourth, like all good consumer redress strategies, you generate a gesture of goodwill for all students – by extending their maintenance loan entitlement (a progressive move by definition) and by waiving the NHS charge for international students.

Alternatively, give them a cash grant as they did just before Christmas in the Republic of Ireland. There all students got a payment aimed at compensating them for the upheaval they have experienced this year, acting both as an economic stimulus as well as a hardship alleviator:

We hope it can go some way to compensating students for any equipment a student may have had to pay for – such as a desk, chair, or new laptop. Covid-19 has disrupted all our lives but for young people, it has resulted in many missed moments and many key life experiences. Today is a chance to recognise that.

Would some students be legally entitled to more over consumer law breaches? Yes, technically. Will most students accept a gesture of goodwill, a removal of disruption and an extension to the academic year rather than the “business as usual” and “equivalent quality” gaslighting required by the compliance documents and legal advisors? Yes. And they’d volunteer to get the vaccination programme going too.

And then fifth, you fund every SU in the country to develop a social capital strategy – one that enables them to ensure that every student continuing into post-pandemic higher education is able to build, nurture and maintain productive and healthy friendships – so that on their return they can resume normal social learning as fast as possible (and for those studying away from home, ensures they have people to live with).

Oh, and yes I know there’s lots not in here – immigration issues, the need for staff to have some proper time off, nations coordination and so on. But the alternative is what, exactly?

Learning the lessons

If this year has taught us anything, it’s that those who left home for some or all of their education will vigorously defend the benefits of doing so as a default. That’s fine – I certainly benefited, and I’ll always be (probably too) cautious about pulling the ladder up behind me.

But we are in the middle of a global pandemic, and even during an actual global pandemic we somehow couldn’t make alternatives possible, palatable or even something people might risk. Young people moving home en masse into densely populated institutional accommodation remained the default – the only “real” way to experience higher education. We should be quite sad about that.

The most frustrating thing is that people still had to do the work to make remote and online work because so many were self-isolating in student accommodation for so much of the time. Academics got good at distance learning – for students who were studying at the distance of half a mile away.

There is now though the opportunity to set some things right and take the sting out of the tale, and in many ways this comes down to a simple balance of risks.

In every other moment in the pandemic a shutdown, lockdown or pause was risky because we had no idea if or when a vaccine would come. Now one is here, the riskiest thing of all would be for anyone to do anything – both inside and outside of higher education – other than help get it into people’s arms.

An excellent, thoughtful article, though it does rather highlight the lack of leadership at UK universities, which is rather sad.

What about all the students that have had COVID? Why should face to face not be re-introduced? What percentage of students have had COVID. Even by year – shouldn’t those stats be driving decisions? My daughter has had COVID as has all her flat and block, – the joy of land locked cruise liners. Before Xmas she was going to lectures with a face mask and visor on why – what is she catching and what is she spreading – the answer is nothing? If the land locked cruise liners did have mass infections – treat years differently – A1st… Read more »

There is no guarantee that those who have had COVID-19 will not get it again, is there!

A brilliant article. But are you including students who have non-university landlords (i.e. most students) in the “shouldn’t be out of pocket” group? Many will have just been home for Christmas, where they are now stuck.

How would these rent reimbursements work, and do you think it’s a reasonable ask to expect the government to fulfil their rent contracts?