How many Black women academics are there in our departments? If we start our conversations around this simple, easy to answer question, we’d immediately recognise that UK universities have a race problem.

Given that public institutions in the UK are purportedly committed to equality, and universities are seen as liberal spaces, one would expect the struggle for equality, diversity and inclusion to be relatively easy.

However, for those of us who are racially and ethnically minoritised in this country, the reality could not be further from this assumption. Universities seem to require external drivers in order to challenge the status quo and prompt necessary change.

In the current climate, those drivers are being realised as a consequence of the abhorrent murder of George Floyd and renewed cries of the Black Lives Matter movement – though there is also a disturbing political backlash against what critics present as a “divisive” diversity agenda.

Even in the UK, between the claims of institutions and the experiential realities of Black and minority ethnic staff and students lies a chasm of white privilege, white silence and silencing, white complicity and white pushback. If anything, the notion of universities as liberal spaces only seems to further obscure serious self-reflection into institutionalised racialisations.

Yet, in a move seen as historic by many Black, Asian and other non-white colleagues, the BME network at our University of Westminster used its collective voice (comprising over 180 BAME* and white ally colleagues) to present a statement of demands to senior managers and work with the students’ union and others to secure a series of commitments from the university to turn it into an anti-racist institution.

These demands are aimed at addressing a collective history of silences, unconscious biases and racism, and focus on forefronting inclusion and (in)visibility, career progression, senior management and leadership, reporting and indicators, and training. Following this, the university published its Black Lives Matter Commitment Plan.

The story of how we got to this place can be told from different perspectives; moreover, it is far from concluded. In fact, we see this as the beginning of a journey that is filled with agitation, hopes, anxieties, and determination.

Allyship

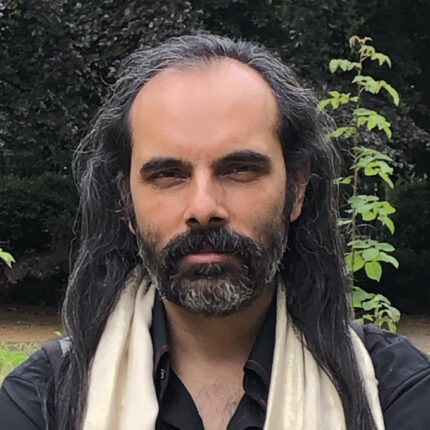

If we, a Black Caribbean woman with strong feelings of un-belonging in higher education and a queer Asian cis-man, as BME network co-chairs could choose one word to describe our story of empowerment, it would be subsumed in “allyship”.

According to the Rochester Racial Justice Toolkit, allyship is “a proactive, ongoing, and incredibly difficult practice of unlearning and re-evaluating, in which a person of privilege works in solidarity and partnership with a marginalised group of people to help take down the systems that challenge that group’s basic rights, equal access, and ability to thrive in our society.”

Reid’s (2019) work describes a continuum where allyship ranges from “apathetic” to “advocate” with promising qualities of “awareness” and “active” in between. As the spotlight on allyship becomes intensified across organisations and institutions, university staff may be reflecting on exactly where they sit along such a continuum and, more importantly, what this might look like in practice.

We offer four examples, beginning with allyship between us two. While the BME/BAME label may put us together as non-white and hence minoritised, we are aware of our differences in terms of gender, sexuality, ethnicity, disciplinary and other identities.

Differences are good. Endless divisions are not. Politeness is a virtue but so is agitation. What brought us together in the first place – and keeps us together – is a mutual sense of trust that has emerged out of years of being focused on challenging the status quo and our resolve to not be erased, patronised, tick-boxed or tokenised.

Our shared vision does not make us oblivious to the fact of privileges that one of us benefits from in terms of race and gender. It is essential that all of us waging this struggle for equality and justice within institutions recognise our different privileges and that one identity is not used to generalise about the other. In other words, “Asian” and “Black” should not be conflated as a “placeholder” for each other.

In the UK, the life and livelihood outcomes for a Black person are much more dire than for an Asian, particularly Indian, person. Numerous reports and blogs have reflected on effects arising from the double jeopardy of the pandemics of race (and racialised disparities) and Covid-19.

Yet, rather than allowing our struggles and differences to divide us, we have chosen to leverage these as strengths. Thus, it is clear from our experiences that people from marginalised ethnicities can be allies for other “more marginalised” people, especially in higher education.

Boundary blurring

Of course, our BME network is more than just the two of us; we are mere representatives. What makes our network expansive and effective is not only the presence of minoritised colleagues but a strong and conscious allyship that challenges the academic/non-academic divide and hierarchy.

Our network eschews academic exclusivity and works hard to embody the immense ethnic and social diversity of professional services and academic staff across a range of disciplines and seniorities. Here, allyship is less translated as “helping” in a remedial sense and more focused on working in partnership to achieve a common sense of liberation. The talent and passion that exists in minoritised bodies is something many white colleagues may not even be aware of.

While being mindful of specific micro-aggressions, exclusions and hyper/in-visibilities that we as Black, Asian or other racially minoritised groups experience, we are fully aware of our intersectional identities as well as the imperative to acknowledge that both power and resistance operate intersectionally.

It has been particularly heartening to work with our colleague Women of Westminster and LGBTIQ networks, who have offered us unconditional solidarity during recent months. We are stronger together. The potentially historic changes at the university would not have taken place without our collaborative functioning.

Equally important has been the tricky issue of white allyship. We are aware that whiteness is not fixed; nor is it unmitigatedly privileged along chromatist lines. For instance, a gay Jewish working class Polish person may experience multiple discriminations that cannot be captured by a single category of “White” or “BME”. Our network has embraced intersectionality and welcomes all allies because we know that both ethically and politically, this makes our task of equality, diversity and inclusion easier.

Senior champions

Our university is one of the most diverse in the world. Yet this diversity was sensed as accidental rather than cherished. Not so long ago, many BME colleagues would have seen senior management as oblivious or even as the obstacle to cultural integration. There has been a big shift in recent years, however, and this is significantly due to a change at the top.

Our most recent vice chancellor and president, Peter Bonfield, is a straight white male who sometimes comes across as more agitational than some of us when it comes to advancing EDI as a social justice principle. Our deputy vice chancellor Alexandra Hughes is co-chairing a new EDI committee along with one of us and is relentless in her efforts to push for change. We do not write this to please any authority but as a heartfelt recognition of these efforts.

Their actions and words make us think of an antonym for the kind of micro-aggressions BME persons often experience in White-dominated spaces: “micro-encouragements”. Where a person’s worth is more often measured by the quantity of their vociferous outputs, active listening seems an almost rare quality among senior leaders. Understanding and tackling issues of racial (in)justice require qualities of “advocate” allyship reflected in the ability to listen, think, unlearn, learn and act. Dr Bonfield and Professor Hughes are listening as much as they push for action.

The end of the beginning

What are the key takeaways from this experience? The agitation that accompanies being in a diverse workforce should be seen as a strength that encourages allyship to shift from a benign state of “apathy” to adventurous “advocacy”. This is part of the necessary churn towards becoming anti-racist.

Much of this can be summed up in recognising the importance of collective action, taking an intersectional approach, mobilising Black and minority ethnic persons, working with white allies, and balancing anger with hope.

Do we think we got what we wanted in the form of an anti-racist university? Certainly not. Between the commitments and actual change lies a minefield of dismantling the status quo. We expect the journey to be neither smooth, nor easy, given the power of complacency and privileges. We are aware that differences can be weaponised to divide rather than unite. We are mindful that cost or resource questions can be evoked to slow down progress.

Our university certainly acknowledges the need to do more to challenge white privilege. But, with a collective determination of many colleagues and having so many allies, we can be hopeful that the journey points towards a more positive future.

*The terms “BME” and “BAME” are applied in a non-homogenous sense, given the diversity that is inherent with ethnicity. A person is defined as BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) and BAME (Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic) if they are African, Asian, Chinese, Caribbean or they self-define as belonging to a minority ethnic group. One way forward is to treat “BME/BAME” as strategically essential to challenge white privilege. Nevertheless, the BME network recognises that these terms are problematic and must form part of ongoing discussions to identify appropriate references to cultural identities.

Systemic problem, goals, and ideology are so well captured and stated. A wonderful beginning on this journey. May it effect iconic and rippling changes within ALL our academic institutions worldwide. Thumbs up to all involved in this endeavor.👍🏼👍🏼