Back in the summer of 2018, things were in some ways all very different. Theresa May was Prime Minister, the sector was gearing up for the third iteration of the Teaching Excellence Framework, and Universities Minister Sam Gyimah (remember him) was busy launching an “app competition” to help students choose between universities.

It feels like a million years ago now in many ways – but one thing that was as important then as it is now was student mental health. The year was characterised by a fresh flurry of surveys, studies and reports all pointing to a concerning picture on the declining state of mental wellbeing in students – and it was accompanied by the kind of repeated media coverage that causes a minister to feel like they have to act, even if they haven’t got any money to act with.

Hence on 28 June 2018, Sam Gyimah convened a summit in Bristol to announce a “package” of three initiatives to support student mental health. Flanked by wellwishers from Student Minds, the UPP Foundation, the Office for Students (OfS), the National Union of Students (NUS) and Universities UK, Gyimah said that it was “not good enough” to suggest that university was about the training of the mind and nothing else – because it was “too easy for students to fall between the cracks and to feel overwhelmed and unknown in their new surroundings”.

One component of the package he scraped together was the formal launch of Student Minds’ University Mental Health Charter that had been funded by the UPP Foundation. Another was the floating of an opt-in requirement for universities to share information on student mental health with parents or a trusted person – an idea that the DfE briefing note framed as a type of “in loco parentis”, picking up both sector and general media commentary as a result.

And the third? Work on “transitions”.

I’ve long had a particular interest in student transitions – I’ve written about the area on the site before, I tend to devour any new findings or studies on the issue, and I’m particularly interested in action research that might indicate what providers and others might do in this space to set students up to succeed.

So it was actually quite interesting to see the announcement of a Department for Education-led working group into the transition students face when going to university, all with the aim of ensuring they have the right support, “particularly in the critical first year [undergraduate] transition.”

In a departure from speeches moaning about the sector, Gyimah announced that the working group would be based within the Department for Education, and the work undertaken was to be “in-tandem” with the sector. And in time, the group was going to form a number of recommendations for schools, colleges and universities to adopt. Great stuff.

March 2019

Quality takes time as they say, so maybe we shouldn’t be surprised that it took over eight months for DfE to announce the actual terms of reference for the group, using University Mental Health Day (7 March 2019) to launch what by then was being described as new student mental health “taskforce”, set up to help students “manage the challenges in university which can affect mental health”.

To be fair this wasn’t just a new press release for an old announcement – some actual thinking appeared to have been done in Sanctuary Buildings to identify four “key areas of risk” that it said could affect the mental health of people going to university:

- Independent living – including things like managing finances, having realistic expectations of student life, as well as alcohol and drugs misuse.

- Independent learning – helping students to engage with their course, cope with their workload and develop their own learning style and skills.

- Healthy relationships – supporting students with the skills to make positive friendships and engage with diverse groups of people. Other risks can include abusive partners, relationship breakdowns and conflict with others.

- Wellbeing – including loneliness and vulnerability to isolation, social media pressures and “perfectionism”. Students may also not know how to access support for their wellbeing.

Secretary of State Damian Hinds was excited, and used his jumping on the bandwagon moment to reaffirm the partnership approach in the Gyimah announcement the previous summer:

I’m delighted to have the expertise of the sector backing this vision and joining this taskforce. Our universities are world-leading in so many areas and I want them to be the best for mental health support too. Pinpointing these key areas which can affect student mental health is essential to the progress we must make to ensure every student can flourish in higher education.”

On the day, Gyimah’s replacement Chris Skidmore held a meeting with students and staff at Kings to discuss the challenges students can face when they transition to university, and had a chat about how universities could work better with the NHS to improve mental health support for students.

It all sounded great – but there was a foreboding sentence in the press note. The announcement said that the group would firstly look at “what works” to help students handle the challenges of moving into higher education and “spread good practice from examples of initiatives”. There’s nothing wrong with trying to identify effective interventions per se, but it can sometimes be a cover for “we have no money”, ” we have no ideas”, or both.

Anyway – the press note is the last we heard of this initiative in public, despite various requests to nudge DfE into telling us something. Hence eventually I submitted an FOI request for what happened next back in May – and DfE eventually responded in late October.

April 2019

It turns out that the transitions group first assembled a matter of days later on Monday 1 April 2019 in Sanctuary Buildings in London – and the attendee list reads like a veritable who’s who of student wellbeing. AMOSSHE, Causeway, the Charlie Waller Memorial Trust, University College London, UCAS, Universities UK, Student Minds, Pearson, the Association of Colleges, HEPI, Unite, Red Brick Research, the Sixth form Colleges Association, NHS England, OfS, the Student Health Guide and UCAS all appeared – as well as a lone representative from NUS.

The readout of the meeting reads very much like the sort of thing that happens at the optimistic first meeting of a working group. The group was hoping to “create the conditions that enable a positive transition into higher education for students”, which was to help them “achieve positive continuation and attainment outcomes”.

There was also evidence of that thing that happens when a group starts talking about students – the note recording someone urging the group to be mindful of language “as 10 per cent of HE is delivered in FE providers”, and being careful not to assume that all students are 18 when they start – “they will be at different points in their lives”.

One thing that everyone was clear on was that between the big names, there was a potentially “massive” online presence with wide reach to different audiences – something the note (and accompanying table describing the reach of each partner) described as “real power to amplify the good practice we identify and quality assure”. In a way, that power was almost as good as having an actual budget:

While it’s not a substitute for funding it would be an effective tool to make a difference on the ground.

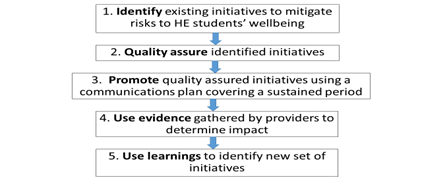

The Charlie Waller Memorial Trust had found that there was a large amount of good work going on but it was scattered – and so the group agreed to take a strategic approach to identifying the initiatives it wanted to back which could include “thinking about themes that cross-cut the four areas of risk identified in our terms of reference” (like loneliness and accommodation).

When you bring together a group like this you’ll end up with lots of diversity – some senior people, some junior, some deep in HE and some offering advice from adjacent sectors. So inevitably and as often the case with these sorts of things, it was resolved that the group would work better with a two-group model – a “core group” meeting (more) regularly and delivering outputs such as the terms of reference, strategic approach and quality assurance and communications processes – and a wider group that advises on the Network’s activity, shares its expertise and facilitates the use of its communication channels.

What could possibly go wrong?

July 2019

The “core group” – this time involving just UCAS, the Charlie Waller Memorial Trust, OfS, Unite Students, AoC, AMOSSHE, UUK and DfE met in July in OfS’ offices in Bristol. Much of the note from the meeting is inextricably redacted, but we do learn that a presented “strategic approach document” would have benefited from an “associated evidence pack”, and that the group felt it needed to be “conscious of end users”.

I thought they meant students given NUS wasn’t on this core group – but they meant HE providers, whose engagement with initiatives would, it was said, be improved if the development of ideas was carried out collaboratively.

Of course if you’re going to recommend initiatives, you need to carry out some quality assurance on those initiatives – you don’t want any old nonsense being promoted. So someone said that the Mental Health Foundation had a QA process for materials it put into primary schools, and one action was to look at MHF’s QA process to see if they could be helpful – although someone else did point out that in implementing an intervention in a school with young people, it’s likely you won’t see the impact until later, such as when they get to university.

Meanwhile it was agreed that the “communications template needed to focus on knowledge mobilisation which included providing opportunities for users to get involved in shaping effective practice”. Parklife!

Later in July 2019

A week later, the (wider) strategy group met – joined by new members Guild HE. More finessing here – a need to describe how and why things work and in what circumstances, and a need to reference underrepresented groups in the approach but also a need to “filter what we do through the lens of the different groups who will be the beneficiaries of good practice initiatives we want to help embed” – as well as a need for “an additional critical success factor around promoting understanding of the blockers and enablers of good practice and also collaborating with colleagues outside of the Network”.

There was some scrutiny of the core group‘s work – it was felt that QA may need to be “situated in the project as well as carried out afterwards”, and “however it works, we need to keep focus on the outcome, not the process” – but the group “may have to accept the limitations of evaluation in proving cause and effect, especially where an initiative is practised in one area but the impact felt in another”.

Then a question. We still need to identify some good things that people are doing, remember. So in identifying initiatives, “do Network members go off and try to identify good things taking place” or “do we put out a formal call for evidence”? After all, we need to be “mindful a call for evidence would be resource intensive”. One for the core group, that.

September 2019

The sector’s core Transitions Avengers assembled again to consider that vexing question in London on 29th September – now fifteen months after Gyimah made the first announcement. It had a few straggling scope and remit issues to clear up first – the group, for example, felt it needed to be clear the Network was not just focused on mental health, but was looking to mitigate risks to general student wellbeing and success.

On that QA issue, it was felt that a “panel” may work best – especially if the group was deluged with large numbers of ideas in a call to evidence – so panels of smaller groups would peer review a manageable number of initiatives. “Themed calls for evidence” would make the process fair and open as well as keeping applications to a manageable number, and there was also an idea to remove barriers to smaller providers by also running categories for different sizes of provider.

And on the question of an effective evaluation framework, there were a “range of potential approaches” – so it was resolved to put an item on November’s full Network agenda to further discuss that evaluation framework.

April 2020

Alas, it looks like November’s meeting never happened – and the next we know of the fate of this exciting initiative is recorded as a Covid-secure dial-in meeting of the core group in April 2020, some 22 months after the Gyimah announcement.

After item 1 – marked “how are we?”, and item 2 – marked “why we’re here”, it was down to business. Everyone shared reflections on Covid-19 impacts on the work, and there was an intention to just crack on and communicate “Leapskills” – Unite Students’ project on supporting young people to better prepare for independent living – as a decent bit of work.

Institutions, it was felt, needed to look at both the “operational opportunities” and the “pedagogical implications” of moving lectures online. There was likely to be a heightened level of anxiety among that year’s cohort, due to the particular issues and stresses of the coronavirus outbreak, including higher than usual levels of family bereavement. And so all were invited to feed in thoughts to DfE on immediate and longer-term mental health support measures, and what they thought any of the unexpected needs might be.

May 2020

In May, now just under two years since Gyimah announced the initiative, the wider Network group met and expressed concern about the current cohort of prospective students arriving at university with unresolved/yet-to-manifest issues relating to the Covid-19 pandemic. It thought that there may also be issues around loneliness due to lack of opportunity to form friendship groups or develop a sense of belonging. All agreed to feedback ideas for what government could do to help friendships and prevent loneliness.

There was a chat about promoting the Unite Leapskills thing, yet another chat about the call for evidence on initiatives and quality assuring them (“if the call for evidence resulted in 20 ideas, 4 or 5 panels would be needed to investigate 4 or 5 ideas per panel”) and it was thought that the work would include a “codesign element”, probably where “relevant stakeholders were invited to input to a document on Teams”, and would likely require “7 to 12 working days from each panellist”. Sure.

July 2020

In July, now over two years since Gyimah announced the initiative – which remember was now hugely important given the impacts of isolation on mental health that were starting to be evidenced – the core group met again. It felt that the role of group might be to “see what’s happening” and “what got legs for the future”, as well as “what keeps happening”.

Something keeps happening, yes.

The view was that the group should focus on transitions on induction and training for students using different platforms – because they might “need different study skills”. As previously, the idea was to focus on what’s worked well and to find out from students on what’s helped with transitions. “NEED INSIGHT WORK” is another sentence in the note.

A chat about those quality assurance panels “building in codesign” and an update on communicating that Unite “Leapskills” project was also included.

April 2021

There’s nothing in the files then until 21st April 2021, with a letter to Network members as follows:

Many apologies for radio silence since the last meeting of the Education Transitions Network on 11 August but there have been a number of discussions about the network in light of the developing situation in supporting student wellbeing in relation to the impacts of the pandemic.

Developments include establishment of the HE Taskforce Mental Health and Wellbeing Subgroup, which is acting as a forum to share good practice and resources, to focus health colleagues on the issues HE students are facing, and to bring in voices from student services, charities and students themselves.

Meanwhile, the Mental Health in Education Action Group met for the first time on 9 March, looking at the impact of the pandemic on the mental health and wellbeing of children, young people and staff in nurseries, schools, colleges and universities, including focusing on mental health and wellbeing as young people return to education settings and experience transitions between education settings in September.

Alongside this, the Secretary of State’s January 2021 guidance to the Office for Students on allocation of government grant funding asks that the OfS should allocate £15m to help address the challenges to student mental health posed by the transition to university.

In light of this, the decision has been taken to demobilise the Education Transitions Network.

Even though none of us is probably going very far away, I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for the great discussions and wisdom sharing that has taken place over the last couple of years”

November 2021

On 15 November 2021, the Office for National Statistics published the third iteration this year of its Student COVID-19 Insights Survey (SCIS). Three in ten students reported that their mental health and well-being had worsened since the start of the term, and 17 percent of students were feeling lonely “often or always” – significantly higher than those aged 16 to 29 years (9 percent) and the adult population in Great Britain (7 percent).

Meanwhile in late October ONS found that 37 percent of first year students showed moderate to severe symptoms of depression, and 39 percent showed signs of likely having some form of anxiety.

As far as we know, the call for evidence from the transitions group never did go out, so initiatives were never evaluated, no ideas or case studies were ever published, and to the extent to which participants “fed in” thoughts on immediate and longer-term mental health support measures, what they thought any of the unexpected needs might be, or ideas for what government could do to help friendships and prevent loneliness, that input simply evaporated.

And so support for the transition of students into and through university – a need hugely exacerbated by the isolation of the pandemic – was never delivered.

Just when they really needed it, a promise by the state to convene experts to help students with independent learning, to form healthy relationships, and to deal with things like abusive partners, relationship breakdowns and conflict with others was unfulfilled. And the promises on wellbeing, including loneliness and vulnerability to isolation, social media pressures and “perfectionism” – as well as students not knowing how to access support for their wellbeing – were never kept either.

I don’t know whether it’s the case that in a sector like higher education, whenever someone identifies a problem there really are endless pockets of best practise both within and across universities, that if only turned into a set of case studies in a shiny PDF, would be magically reproduced around the country to fix the issue. What I do know is that that it’s a strategy that feels tired, ignorant of the capacity and funding issues, and ironically given how it’s framed, appears not to work.

Although it is a strategy that has a better chance of working if you get round to actually attempting it, rather than talking about attempting it for two years.

It’s this simple really. If students didn’t really ever need the group, why did ministers announce it? If they did, why did it fail so hard? What does all this tell us about the apparently utterly dysfunctional operation of a cross sector government working group operating in the student interest? And when is someone going to apologise to students for the spectacular W1A-style failure of this project either way?

Interesting story.

When there has been a clear call for action, the Civil Service manual seems to suggest that the first requirement is to set up an investigation unit. The next chapter dictates the creation of an inter departmental / multilateral working party (this is to ensure total failure) in case the initiative makes progress.

We need to understand that the Civil Service is there to investigate, analyse, recommend and possibly produce a policy but must never actually do anything.

The response to Covid 19 is an excellent case study.