Like everyone else I thought this year’s Autumn Statement was going to focus on the cost of living, energy and fuel prices. For all I know it might have done but I haven’t yet got past the announcement of 30,000 extra university places next year and the abolition of all number controls in 2015-16. That on top of 20,000 new high level apprenticeships and money for new science facilities across the UK.

After all of the arguments about both the affordability and the desirability of a mass higher education system, George Osborne has come down firmly and decisively in favour of both. I thought we had lost that debate – that faith in mass human capital and the knowledge economy had been irreparably damaged. I was wrong and I’m pleased about that.

That should be something to celebrate. Back in October I wrote about the tensions between economic and social conservatism -the competition and markets of the former versus the rhetoric of only the brightest and best in the latter. well now we know where George Osborne stands – and it’s alongside David Willetts in arguing for a bigger, more competitive, more dynamic system. Perhaps both their and David Cameron’s recent trips to China have finally convinced them that mass higher education matters. Watch out Theresa May for they may also have been persuaded that the Chinese shouldn’t only think of the UK as ‘a nice country to visit or to study in.’

Of course we need to see more of the detail. It’s fiendishly difficult to disentangle the costs of expansion from the sales of old loan books as well as the shifting RAB charge on more places and more loans. In the longer term this may not add up quite as well as today’s costings from the Treasury suggest. In particular it may yet be that expansion is just too dependant on risky asset sales.

But for now my understanding is that these are fully funded, full time places – and not an attempt to grow through part time, lower cost or alternative models. There will still need to be some ‘control’ but it is likely to be through legislation in the next parliament that this is achieved. A steep demographic dip in 18 and 19 year olds as well as more choice through high level apprenticeships will provide some additional buffering.

But it looks to be a ‘game-changer’ on several levels.

There will be more places AND more competition – great news for those institutions already doing well – more worrying for those that aren’t currently able to reach their target numbers under the existing system. In 2015-16 with no number controls for anyone – including alternative providers – the competition for students will intensify and those losing out on the margins of ABB may now squeeze more from less popular universities. And from lower cost competition from the private sector too?

Politically it drastically raises the stakes for Labour ahead of 2015. The system is working and we are going to expand it – furthermore we are going to go beyond the 50% target that Blair set over a decade ago (with the demographic dip in this proportion may go as far as 60%). It might free Labour to think just as radically – no longer constrained by the costs of expansion or of similar suspicions about the ‘value’ of higher education. Whoever comes to power in 2015 will have to legislate and to frame a new system. They may also have to find new ways to pay for it. But now we know that this is likely to be a bigger system, with more students, more universities and other providers and ultimately more graduates.

What of last week’s rumoured ‘black hole’? Well something obviously still needed filling. Private providers still get a tight number control for this year and next (though they will be happier about the promised ‘level playing field’ for 2015-16), the National Scholarship Programme is all but over and it looks unlikely that any of the 30,000 extra places will be filled by people with Bulgarian or Romanian accents. But in the context of expansion, any overspend this year simply matters less. The Treasury has changed its mind. Often cast as the pantomime villain, today it has become higher education’s fairy godmother.

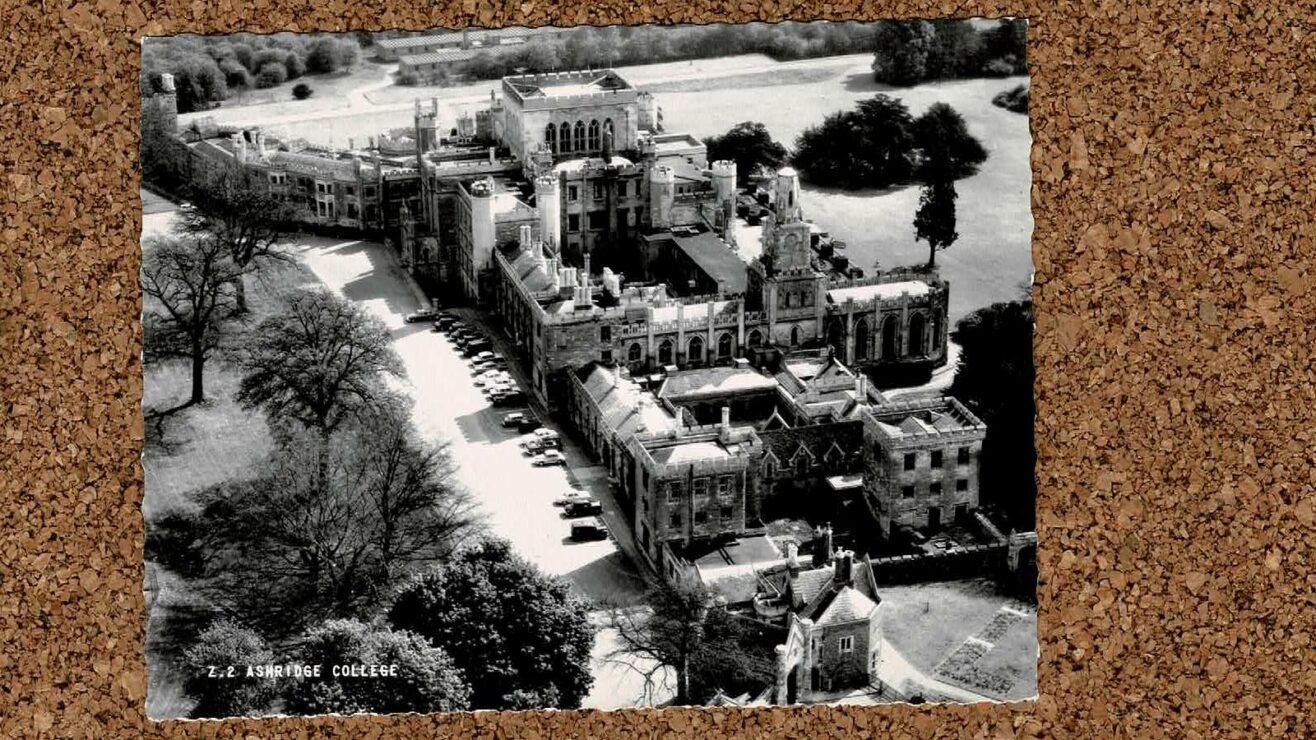

And so the last word should go to David Willetts and his championing of the Robbins report on its 50th anniversary – a time when Britain was perhaps more optimistic about its place in the world. We might not agree with the funding system that we have, we might not even agree that it can be sustained for the longer term, but we should agree that he has consistently made the case for expanding higher education. And today he won that argument.

While I share your pleasure at the unexpected windfall this statement brings to UK HE, my delight is tempered by a concern that this is pre-election sleight of hand, to some extent. I can’t see how 30,000 additional numbers can be absorbed, mid-cycle. This is a much larger scale increase than the old ASN programme, and it must surely be unrealistic to expect that many institutions will have capacity to absorb a large scale increase in numbers in September – courses ready designed and ready to roll out? Spare capacity in existing courses? – what will be the impact on… Read more »

Hi Andy,

That’s a great analysis and very helpful for those of us trying to get our heads round today’s surprise, thank you.

I wondered if you think that having abolished the student number cap, the lifting of the fee cap would be the next logical step for a government that seems keen to create a genuine market in the UK HE sector? I may be overly cynical, but I did wonder if this universally welcomed announcement may be a precursor to something more controversial.

But, as they say, you should never look a gift horse in the mouth!

It’s Browne’s plan for expansion to enable suppy to meet demand – classic prerequisite for the market mechanism to work ‘efficiently’. And when markets work efficiently we end up with prices falling which, if it happens quickly enough, will save the Government’s public funding bacon. But the likely impact on the sector is to drive down fees and that will make it harder to sustain the wider mission of universities – research and a broader range of courses offered to all that feel they would benefit from them and are qualified – in all but the elite institutions. The rest… Read more »

Thanks all for reading and for your comments. I think it’s definitely an expanded ‘market’ system as well as an expansion of places. On that basis I would expect more competitive behaviour and more market dynamics and consequences – and ultimately that could include both lower and higher fees. I’d expect BIS and HEFCE to go for a range of mechanisms for the extra places next year – the most obvious being a greater tolerance band for popular institutions? But they could find other ways to support specific subjects and sectors too – following some of Witty’s and Heseltine’s broad… Read more »

Mass higher education is certainly to be welcomed but let’s not kid ourselves it builds ‘mass human capital’ or contributes to a ‘knowledge economy’ – whatever that is! Rather, with persisting mass youth unemployment and the degredation of what work there is (40% of jobs available to young people now require a degree to enter if not to perform!), the strongest argument aginst fees and for more F&HE is – what else are they all expected to do?