The outrage that met revelations from Durham University at initial proposals to massively restructure its operation in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic – and the apparent lack of engagement with student reps in the initial development of the plans – suggests and signals an institution’s attitude to student engagement, amongst other things.

It is totally understandable, after all, for such serious deliberations as these to be made behind closed doors by senior management. And yet for those in the sector who are invested in the idea of student engagement, the act of excluding experts in student experience – students who actually live that experience – will seem woefully short-sighted, no matter how complex, sensitive or early in the decision-making process it may be.

Weasel words

For those of us who work in student engagement – and there are many of us in universities, students’ unions and others partner organisations – Durham’s decision to exclude student representatives from the process is perhaps frustrating, but really not all that surprising.

The term “student engagement” is frequently bandied around as a key tenet of the sector, but despite the large communities of practice, legions of consultants and growing body of academic work, the sector’s understanding of student engagement is often so woolly and subject to interpretation that it risks becoming a “weasel” term that is increasingly meaningless in its application.

And for every person reading this who is reaching for the latest textbook, conference note or policy paper to point out a very clear definition of the term “student engagement”, there will be one or two more who are rooted in the practical business of engaging with students and recognise in a heartbeat some of the day-to-day challenges around meaningful student engagement.

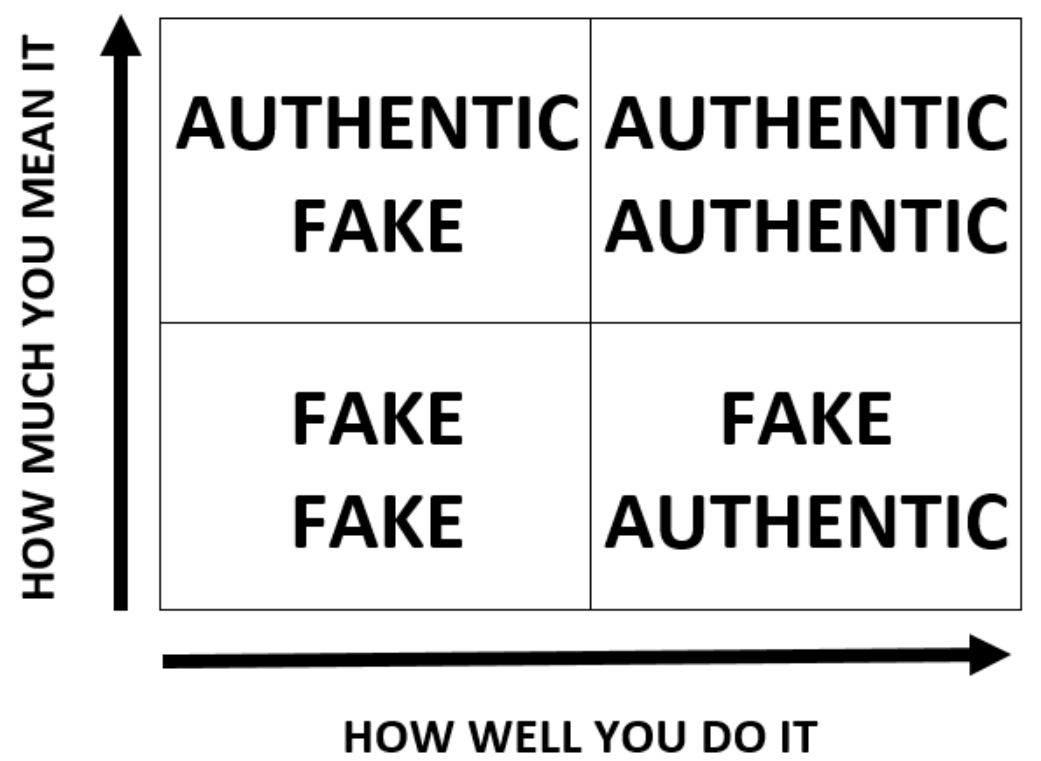

Here is a simple chart, highlighting what happens away from the theory when we start looking at practice: a simple juxtaposition between student engagement when you really mean it and when you don’t, cut against student engagement when you’re really good at it and when you’re really not.

Authentic Fake Student Engagement (you mean well but do it badly)

Hand-picked students are wheeled out, handed the furniture catalogue and given have free choice over what to fill the building with. Yes, they do have choice (within a budget) but have they had any say in what the building is for, who’s going to use it, what were the design choices etc?

No. This tokenistic approach could be seen to have some value; it ticks a box and nods towards what students want, but is limited in meaning and puts the gloss of student engagement over what is otherwise a project devoid of student input.

Fake Authentic Student Engagement (you do it well but don’t mean it)

“Student feedback” is gathered together and analysis shows that students want or even need a particular intervention, which bears uncanny similarity to what was in the departmental business plan a few years back.

When the student reps get involved, they start asking all kinds of difficult questions: which ‘student’ is the feedback supposed to be from? Where are the minority voices? Strangely the original group of students now start to give different answers to the same questions. This disingenuous approach acts as an antagonist to the informed student voice, leaving few, if any, satisfied with the outcome.

Fake Fake Student Engagement (you don’t mean it and do it badly)

The PR exercise which claims student engagement, but in reality was a minute noted in a meeting that no one can quite remember discussing, or a brief corridor chat. Both make their way into the business case as “students were consulted fully in the development of this proposal”. The box is ticked and approvers are happy, but the idea of meaningful and informed engagement is totally lost.

Authentic Authentic Student Engagement (you mean well and do it well)

Here’s the Nirvana and no it’s not just about elected reps – but about a mindset where students are engaged at all different levels, playing a key role in deciding what needs to be decided.

There’s a combination of quality research with active student participation, and a strengthened role for minority voices, built around a common purpose. Here we see the active delegation of power to students (and others), with lived experience and collective intelligence coming to the fore in decision-making.

Getting it wrong

Whilst there are sure to be plenty of great examples of truly authentic authentic student engagement delivering exceptional outcomes for individuals and institutions, there are far too many unwitting examples of institutions getting it wrong.

Too many reps, like those at Durham, exasperated by the approach taken by the institutions they are part of. Too many minority voices lost in the mass of gathered “student feedback”. Too many students who don’t get involved in their students’ unions because they don’t see the point and can’t make head-nor-tail of how to affect changes they want to see.

As higher education has expanded and embraced a more transactional “consumer” model, student engagement’s role has increasingly been to find out “what students want”, often post-rationalising already-made decisions. Often confined to discrete transactional “market research”-type activity done in isolation only by certain teams or people with no context, this is a poor proxy for student engagement and a concerning development for a sector that has always implicitly understood and championed the benefits of meaningfully involving students and other stakeholders in decision-making.

As the Office for Students sets about ramping up its student engagement work, it’s clear other countries have enshrined both a regulatory framework and culture that enshrines active student engagement through involvement in decision-making . As part of the Baltics study tour organised by Wonkhe earlier this year, we saw students and professional services (that’s a whole other Wonkhe article) enshrined as equal partners in ALL decision-making, making up equal thirds of ALL committees throughout institutions. When discussing student matters, students in Latvia hold a rarely-used veto on decisions, reflecting a strong commitment to the understanding that it is students who are the experts on student experience.

As we enter the biggest period of disruption that the sector has seen, we have some important decisions to make. Do we still value student engagement/participation in decision-making? Does this collegiate approach reflect the identity that higher education institutions want to create? Can we move on from the concept of student ‘feedback’ representing the ‘whole’ of the student body? Can we strengthen minority voices in decision-making? If so, I’d suggest we need to evolve our thinking rapidly. If not, maybe it’s time to cut this loose and stop pretending it matters.

The next evolution?

What is interesting about the age that we are entering is that increasing numbers of organisations – commercial, charity and public sector alike – are moving towards, rather than away from, the principles of engaging users/customers/members in their work. They are doing this because they can see the benefits of working in this way, creating value, loyalty and resilience through a mindset which gives real agency to those people at its heart.

Rather than being discrete pockets of activity, this approach becomes a core way of working, embedded in all strategies, which not only deepens relationships but is also an inherently better way of achieving whatever the shared purpose of your organisation is.

The team at the New Citizenship Project have dubbed this the #Citizenshift as we (society) tire of being treated as subjects or mere consumers, and begin to demand greater agency in the organisations that we are part of.

As a sector – universities and students’ unions alike – we are, in theory at least, already in the mindset of student agency. We’ve just become distracted from its purpose. But are we bold enough to do it in practice too, ditching the fakery of student engagement and moving to something with more meaning that’s closer to the principles of how this whole thing started? Isn’t that agency and purpose a central component of what we still describe as “higher education”?