Regular readers will know that Jim loves his Eurovision and student politics links.

About 51 years ago, at 10:50am on 24 April 1974, the song “E Depois do Adeus” by Paulo de Carvalho was played on Rádio Emissores Associados de Lisboa.

Like plenty of Portuguese entries,1974’s effort (which translates as “And After the Farewell”) went on to come last.

But it wasn’t just a promo for the Brighton event otherwise notable for an Abba win – it was a secret signal, used by the left-wing Movimiento das Forças Armadas (MFA) to signal the start of a military coup against Portugal’s fifty year-old fascist dictatorship.

It had been over a decade in the making. Fourteen years earlier, António de Oliveira Salazar’s Estado Novo regime had attempted to dissolve independent student associations and replace elected representatives with regime loyalists.

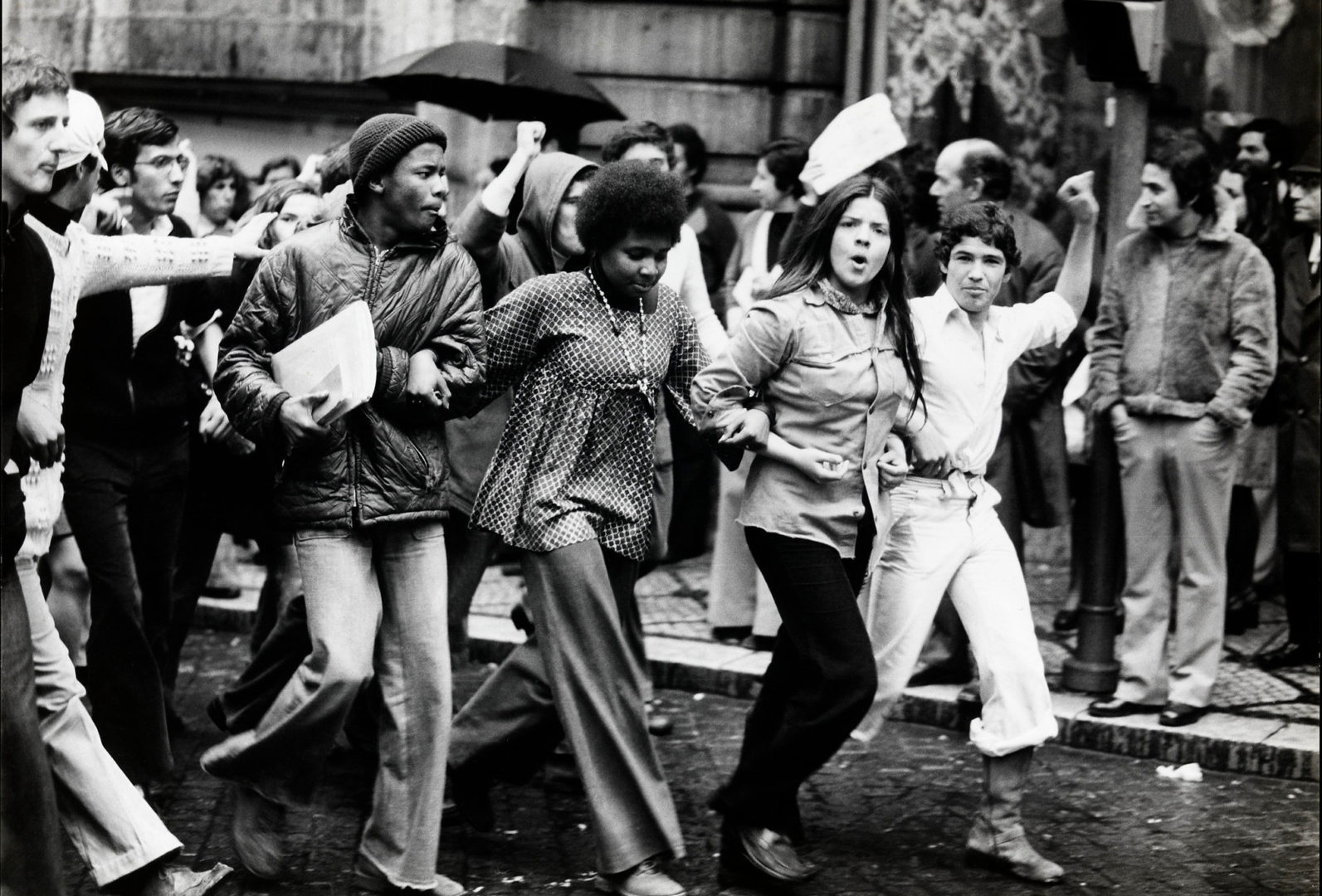

On 24 March 1962, students staged a full-blown general strike in Lisbon and Coimbra, refusing to attend classes and demanding academic freedom, the legalisation of SUs, and an end to state interference.

Then came the crackdown. Riot police invaded the campuses, wielding batons and dragging students into unmarked vans. The scale of the violence shocked the nation – at the University of Lisbon’s Rectorate, students were surrounded, assaulted, and arrested en masse, and some were sent to Caxias prison – famous for its use in detaining political dissidents.

Like lots of student uprisings of the period, it’s not that it was immediately successful – it was the way in which it radicalised a generation that went on to realise their ambitions later. Those politicised by the crisis graduated into Portugal’s civil society, creating pockets of resistance that slowly expanded. Some joined clandestine networks – others worked within the system, gradually challenging from within.

Jorge Sampaio, a law student during the protests, would later serve as President of the Republic (1996-2006). Manuel Alegre, a student in Coimbra, would become a noted poet and socialist politician whose work captured the spirit of resistance.

Francisco Salgado Zenha, a Coimbra law professor, supported student activism and later co-founded the Socialist Party, serving as Minister of Justice. José Mariano Gago, active in the student movement in the late ’60s, later transformed science and education policy as minister. And Helena Roseta, expelled for activism, became a leading voice on housing and civic rights.

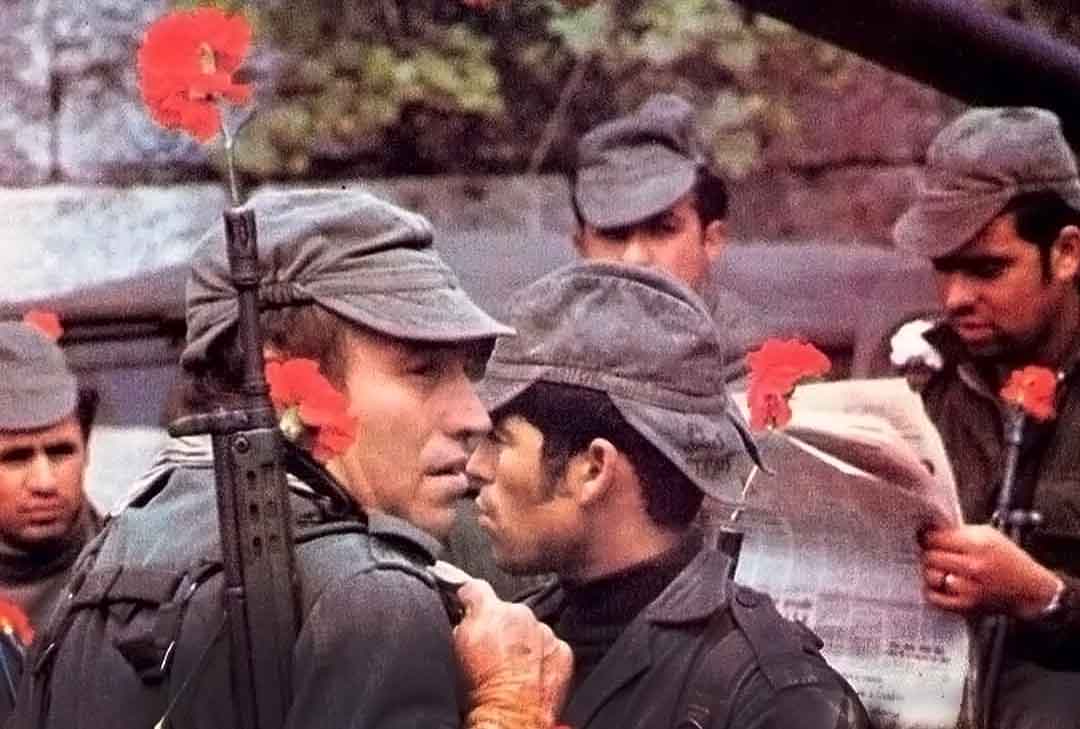

By 1974, the student ideals of 1962 had also worked their way into the military academy, influencing the younger officers who formed the Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA) and led the Carnation Revolution. And so, on that April night, after “E Depois do Adeus” signalled the first movements, another song played at 12:20am – “Grândola, Vila Morena” by Zeca Afonso.

With more overtly socialist lyrics celebrating fraternity, that song – one that had been banned by the regime – became the definitive go signal for troops to seize key locations.

Students put red carnations into the muzzles of soldiers’ guns and on their uniforms as a symbol of non-violence – and within hours, almost without bloodshed, the 48-year dictatorship collapsed.

Today 24 March has become a National Day of Students – and last month thousands of students rallied in Lisbon’s Rossio square, demanding an end to tuition fees and greater investment in higher education as soaring housing costs force many to abandon their studies.

Waving red carnations and chanting slogans, they called for a return to the spirit of the 1974 revolution – one that promised opportunity, not exclusion.

No to precariousness, yes to dignity

It’s one of the remarkable stories we’ve been discussing on Day -2 of our Wonkhe SUs mini-study tour to Portugal.

On Wednesday around 30 students’ union officers and staff from across the UK will make their way to the Portuguese capital of Lisbon to begin a short trip aimed at building links with and learning from others representing and serving students – and to prepare, we’ve been boning up on our history.

Post- the Carnation revolution, there was an explosion of democratic energy on campuses. Student associations were re-legalised, elections were heavily contested, and universities became key breeding grounds for political engagement.

In the 80s as Portugal joined the European Economic Community (later EU), while the revolutionary fervour cooled, activism shifted from existential resistance to policy-focused advocacy.

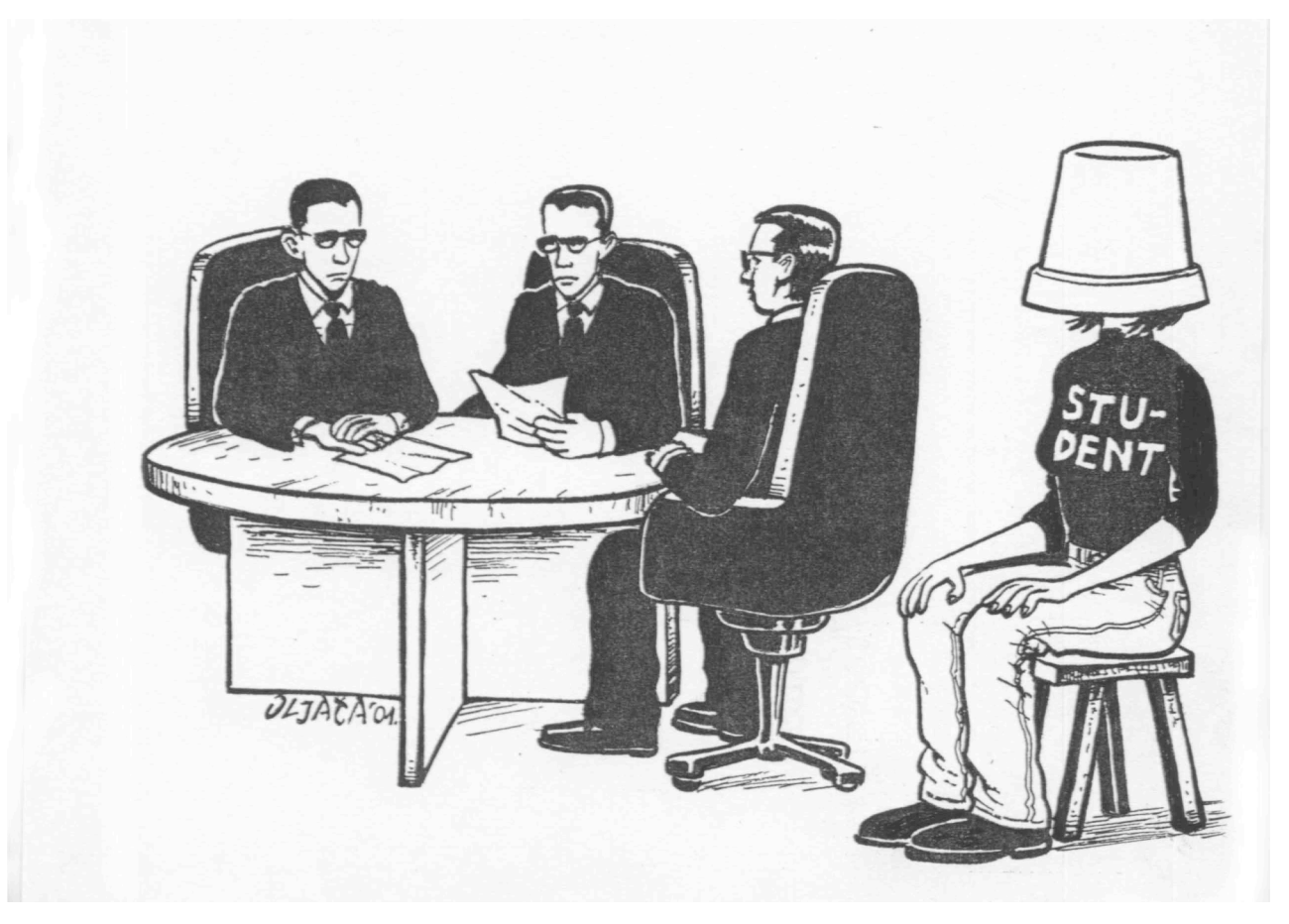

By the 1990s and early 2000s, a new generation was mobilising against austerity and the encroachment of “neoliberal policies” in higher education. Tuition fee protests became common, and the Bologna Process, intended to harmonise European higher education, caused huge scepticism among students who thought credit commodified education:

Unfortunately in Portugal Bologna is being served to students as a fast-food dish. What does this mean? It means that students are not really having the possibility to participate in the cooking of the Bologna dish, and this is happening at al the levels, from the department level till the national level. There are a few exceptions to this scenario, but they are only that… exceptions! In the best cases student are presented with the cooked Bologna dish and are being asked if they like it!

It has been written several times that in the heart of the Bologna Process there is the change in the paradigm of an education centred in teaching towards a learning process focused on the student outcomes. This change of paradigm will only happen if the students’ and their representatives are included in the slow-food process of cooking the bologna dish. Otherwise, Bologna will only be a minor operation aimed to change a little the taste of the dish students in Portugal are being served for several decades.

That all culminated in a series of strikes in 2009 that saw thousands of students join academics and other workers across Portugal boycotting classes, demonstrating in the streets, and staging symbolic “funeral processions” for public education.

Portugal’s Education Ministry under the Socialist government maintained the Bologna framework to avoid isolation from European higher education – but students won enhanced social maintenance packages, increased student consultation in institutional planning, and themselves created a generation of student activists who went on to establish new advocacy collectives and participate in national and EU-level politics.

The essence of democracy

Today Portugal – like plenty of European countries – has an ageing population and low birth rates, plonking students and higher education right at the centre of debates on economic development, housing and emigration.

The county’s housing crisis has become particularly acute in university cities like Lisbon, Porto, and Coimbra, where gentrification, tourism, and underinvestment in public accommodation have created severe shortages. Students have responded by building occupations, joint campaigns with broader housing movements, and piling on the pressure for regulatory interventions.

In 2021, that all led to a dedicated National Higher Education Accommodation Plan (PNAES), which will see the country’s largest investment ever in student accommodation – affordable student housing is set to increase 80 per cent from 2021 levels. Even Prime Minister Luís Montenegro is involved:

It is repugnant, from a civic point of view, that a student can battle for twelve years to enter higher education, only to find they cannot attend because they have nowhere to stay near the institution that accepted them.

In his words, the failure to provide housing “frustrates people’s efforts, stifles their ability to develop their talent,” and undermines the promise of equal opportunity. It’s almost as if opportunity is linked to housing. Late last year he described the inability to accommodate students as a broader injustice — not just a failure of planning, but a democratic failing:

The essence of democracy is the ability for all citizens to have the same opportunities, regardless of their economic background or where they were born or raised.

The big debate over the past year or so has been over reforms to the Regime Jurídico das Instituições de Ensino Superior (RJIES), the government seeking to modernise governance in both universities and polytechnics.

Among the proposals were enabling polytechnics to transform into polytechnic universities, the facilitation of institutional mergers, and introducing direct elections for rectors and presidents via broader electoral colleges – including students and alumni.

Mental health was a major issue – students highlighted dangerously long waiting lists and patchy services – and now universities will have a statutory duty to support student wellbeing via the mandatory provision of mental health services

And following complaints from students over fair treatment in cases of academic appeals and harassment, the country’s system of Provedor do Estudante (Student ombudspersons) will be strengthened in law, with defined competencies and a formalised election process to ensure accessibility, independence, and consistency across institutions.

We’ll kick off properly on Thursday morning in Libson, where we’ll be hoping to find out more about last year’s big push on non-continuation and health. As it stands, around 11 per cent of students entering higher education drop out by the end of their first year.

Convinced that the situation can be counteracted by improving students’ well-being and quality of life, the government signed protocols with psychologist and nutritionist associations at the beginning of September 2024 – which will provide 100,000 psychology and 50,000 nutritionist consultations at higher education institutions. A student health strategy! Imagine that!