Everyone has a theory of change these days.

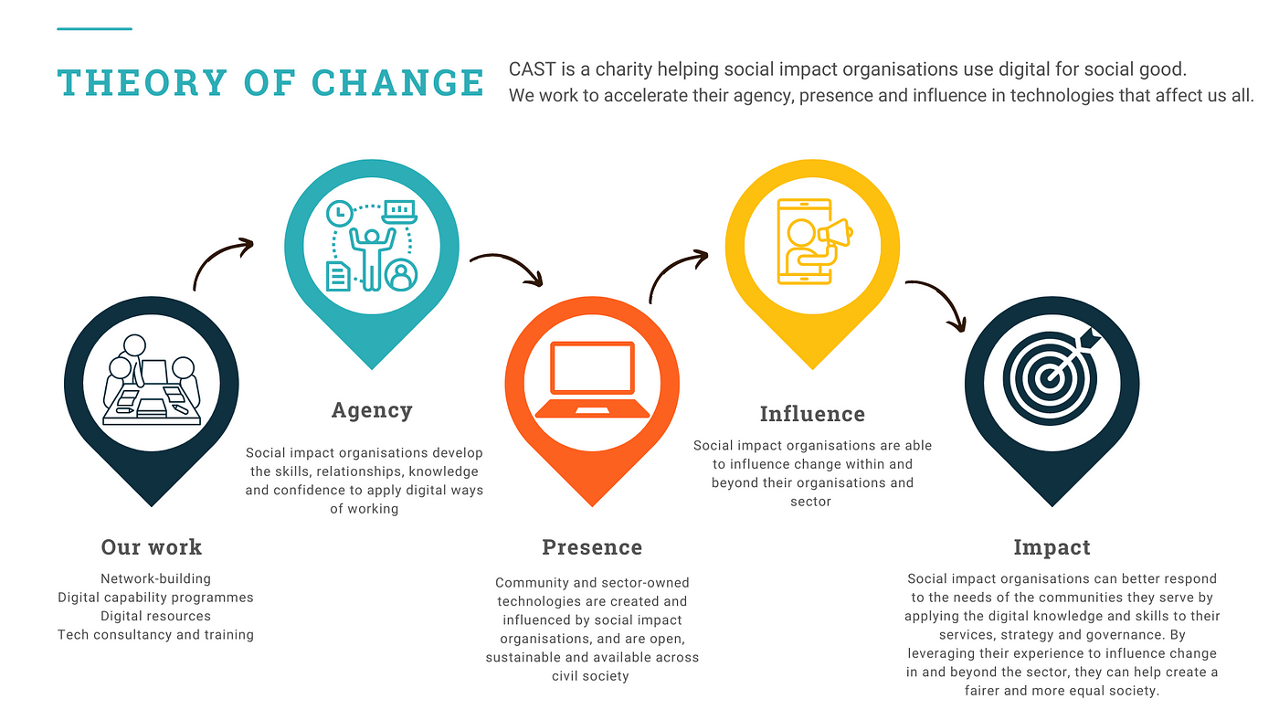

Here’s one for a charity helping social impact organisations.

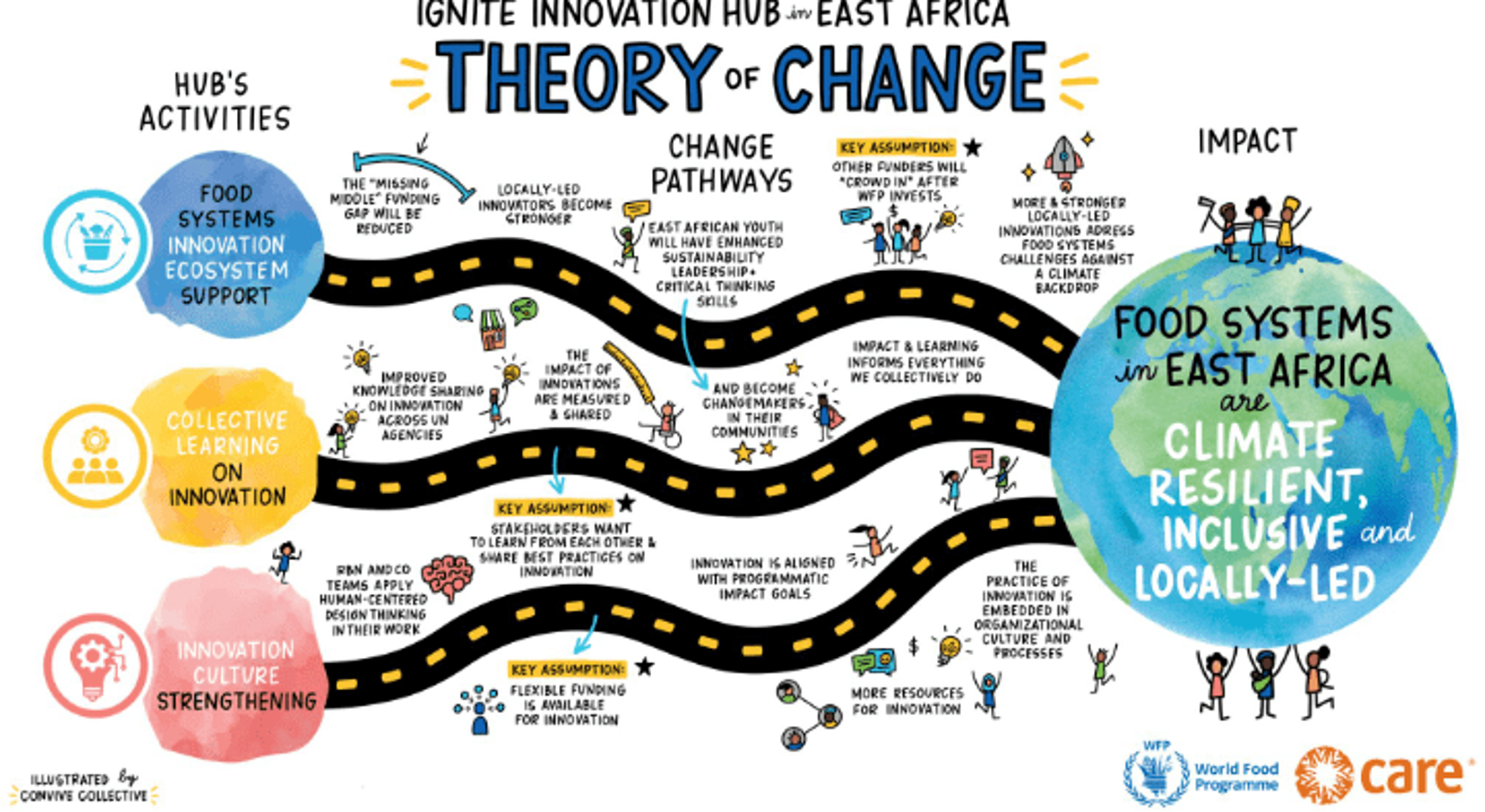

Here’s one for the World Food Programme.

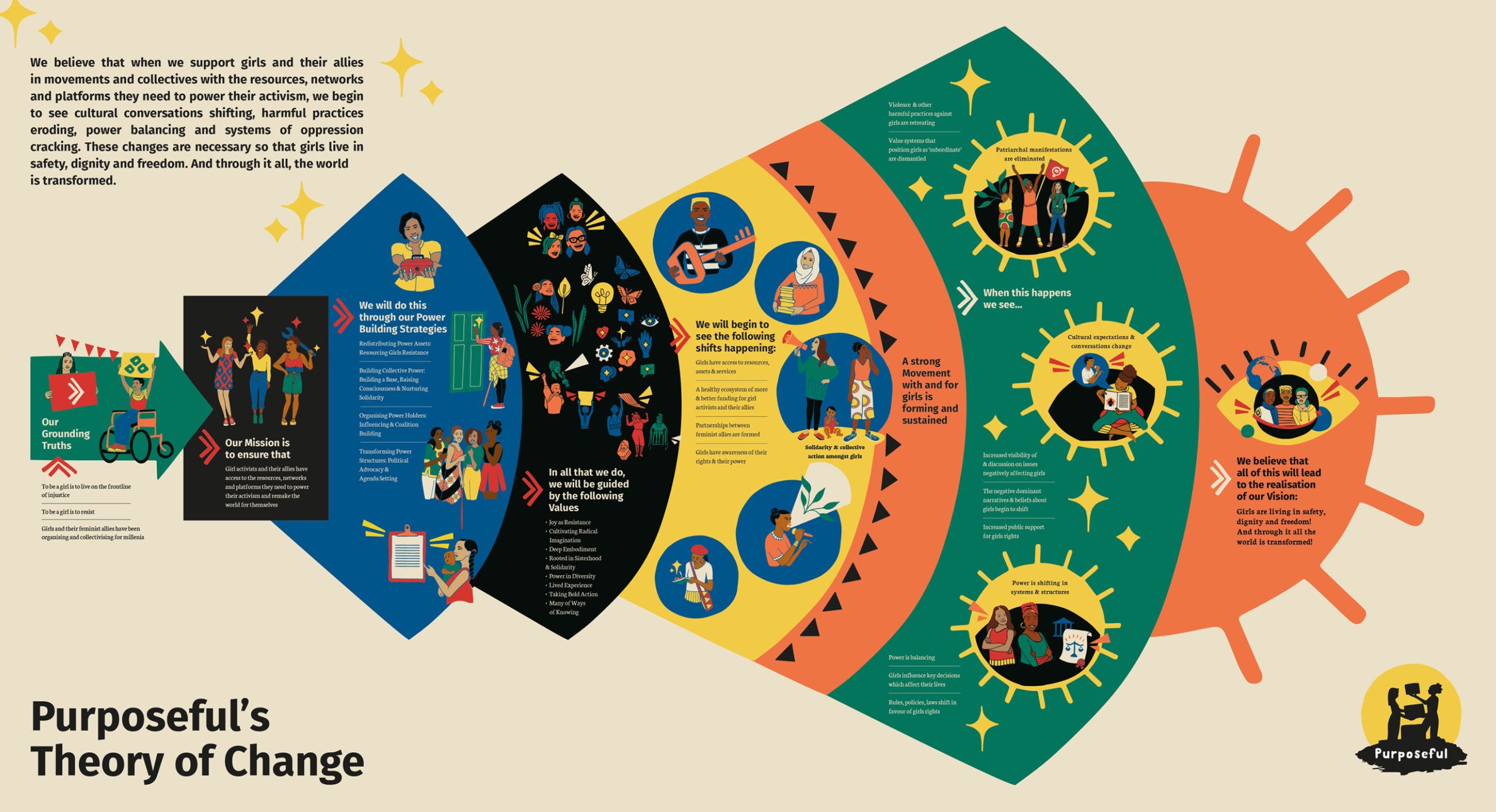

Here’s one for an organisation called “purposeful”. They would, wouldn’t they.

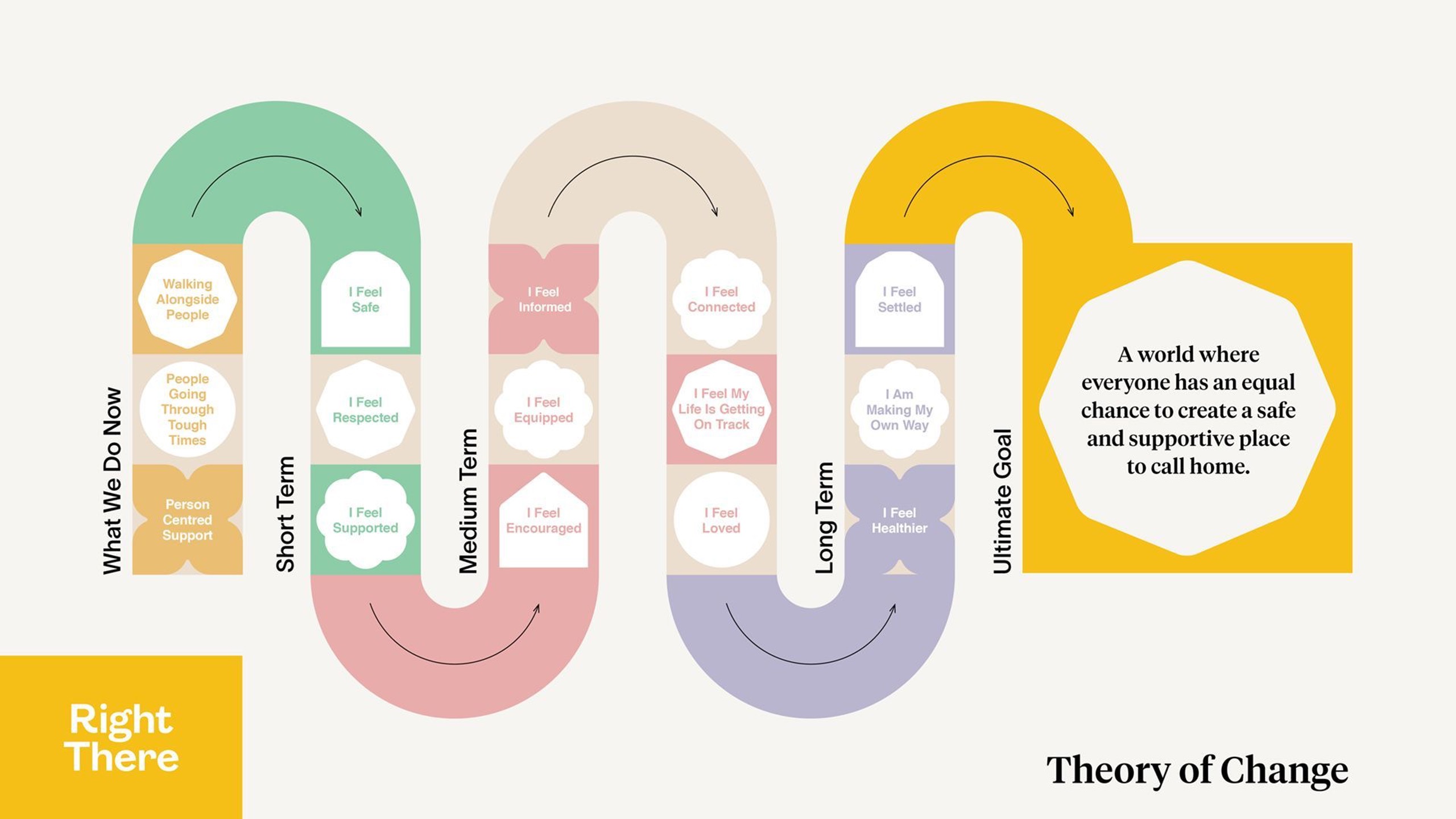

Here’s another for a homelessness charity.

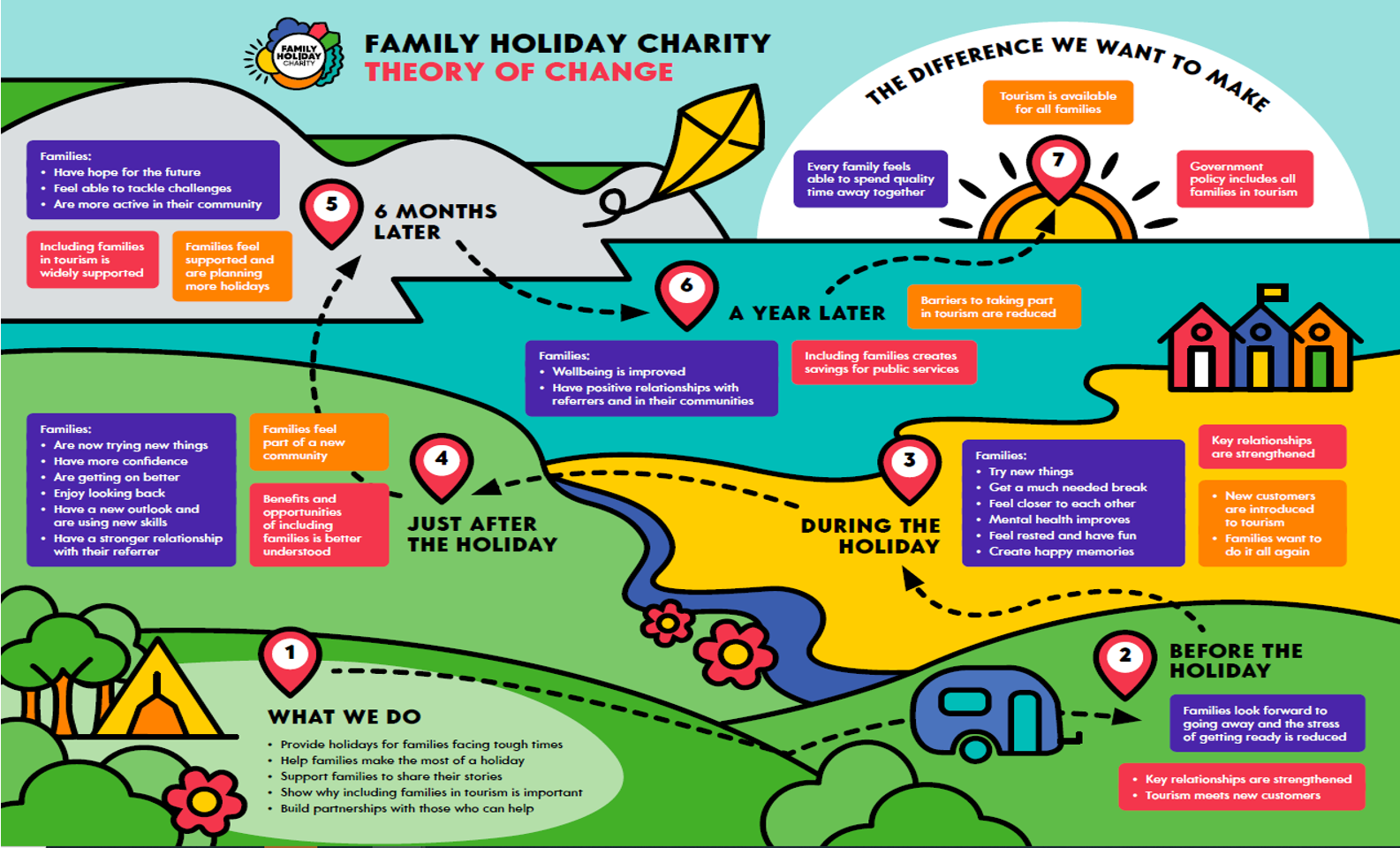

Even this family holiday charity has a theory of change too.

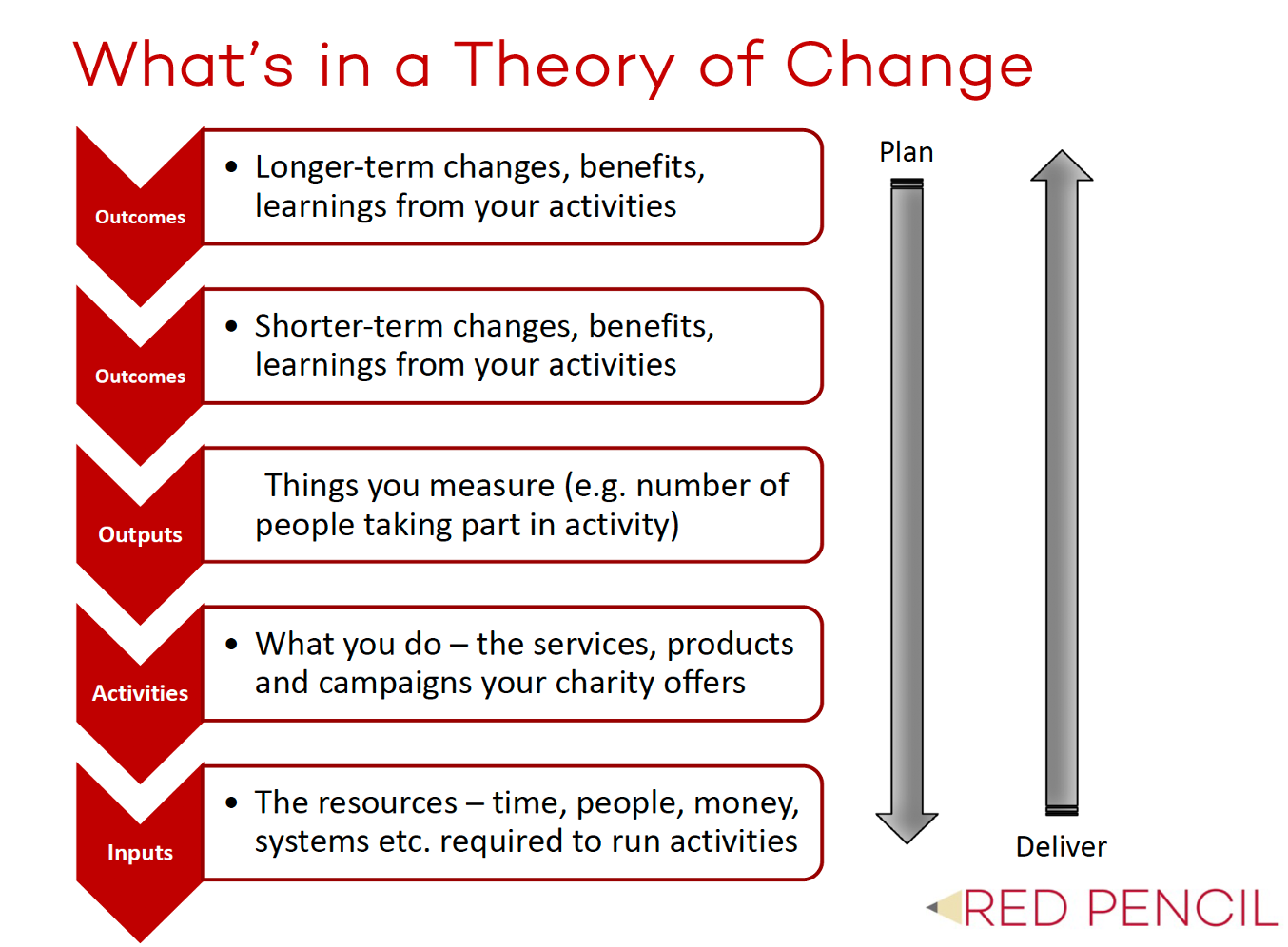

A theory of change is a comprehensive explanation of how and why desired changes are expected to happen in a particular context.

They outline the steps or interventions needed to achieve a long-term goal, detail the causal links between activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts, and identify assumptions and risks that might influence the process.

It’s a thing that’s becoming very popular in strategic planning and evaluation.

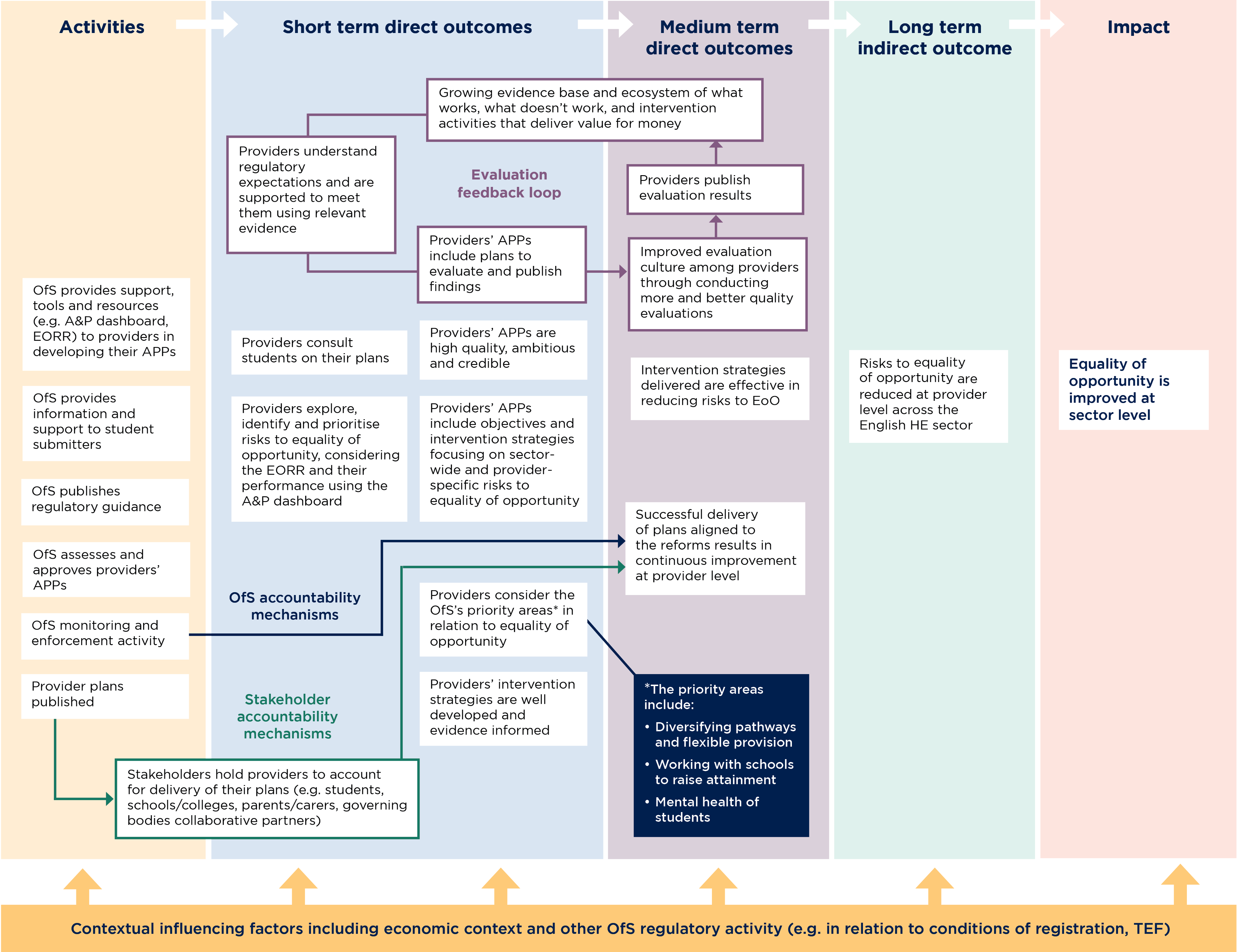

They’re not only popular in the charity sector, they’re becoming popular in higher education too.

In a recent review of the Teaching Excellence Framework that Advance HE carried out, it said that providers had “changed or enhanced their frameworks” and that some had adopted “theory of change principles”, which it said can “help pin down key purposes, actions and approaches to evaluation” for student success.

Probably the most common use of theories of change in higher education are those that surround access and participation. The idea being that if you know in theory what you have to do to cause something to happen, if it works, you can then do it again with other people – and as a result, you’re much more likely to have an impact.

The Office for Students’ own version for access and participation is quite a thing to behold:

The use of theories of change in students’ unions is officially relatively sporadic.

But of course, there are some underpinning theories of change, even if we don’t write down the de rigueur phrase.

Be the change

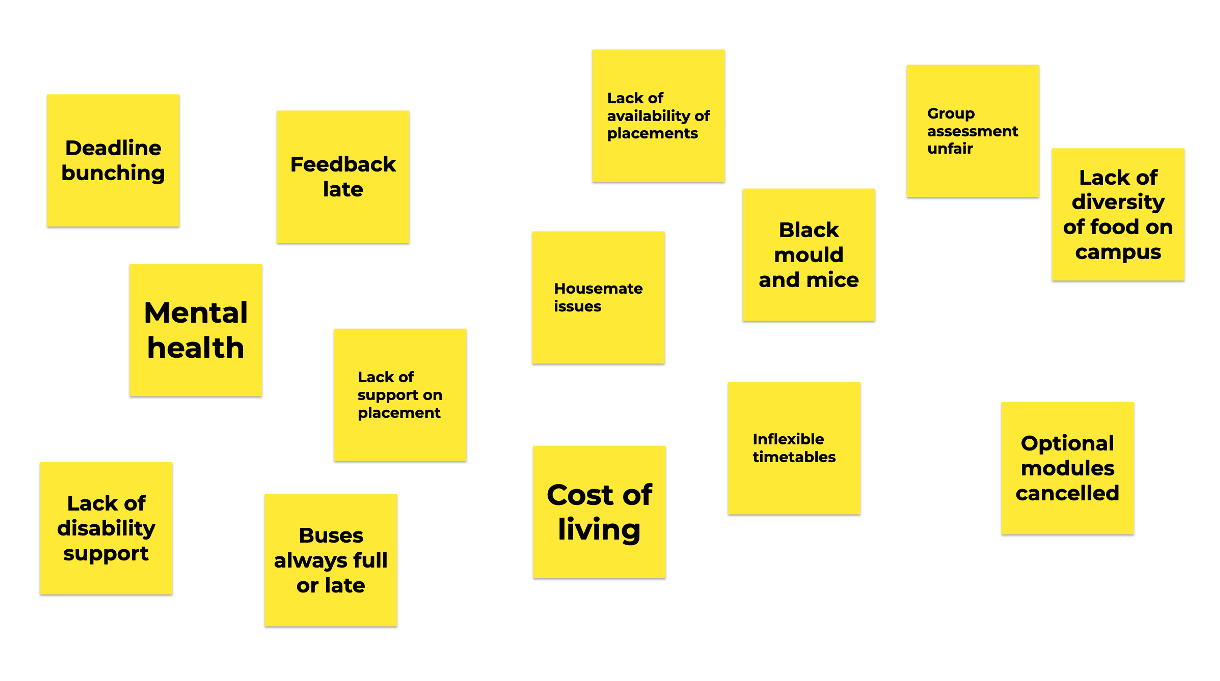

Take all of the kinds of issues that student officers will either put in their manifestos or that students will complain about that they would love to see fixed.

One way of thinking about those issues is to think about what you do about them.

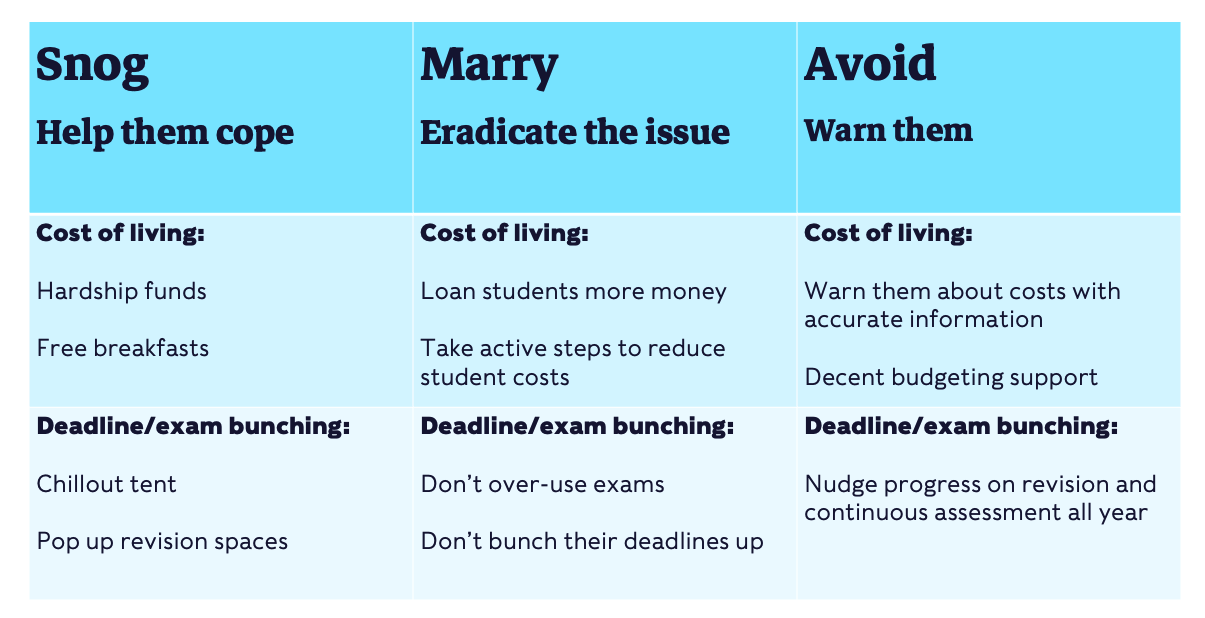

One of the simplistic heuristics that me and Mack have been using over the summer is this “snog marry avoid” approach – where:

- avoiding is causing students to know that something might be coming. And so the theory here is that if we warn them about it, they can take steps to avoid the problem.

- marrying is about eradicating the issue altogether so students don’t have to experience it.

- snogging is about helping students to cope with the issue when they face it.

So for example, if we take the cost of living crisis, one of the things that we can do is warn students about the costs that they’ll face with accurate information, and give them decent budgeting support so that they don’t run out of money.

One of the things that we can do is campaign for or provide hardship funds or free breakfasts when they do run out of money.

But crucially, what we can also do is marry the issue, eradicate it altogether, either by (in the case of home domiciled students), loaning students more money, or by taking active steps to reduce the cost of things that students will spend money on.

Similarly, if you take the classic problem of deadline or exam bunching, you could nudge students to make progress on their revision and develop more continuous assessment approaches.

You could, when they face a real problem with bunched deadlines, provide a chill out tent or some pop up revision spaces. But what you can also do is marry the issue – campaign to make sure that the university doesn’t overuse exams in the first place, or doesn’t bunch deadlines up by making some radical changes to the assessment or curriculum model

Having read pretty much all of the manifestos that student officers have presented this year, our sense is that SUs have an over reliance on snogging problems – perhaps inevitable when student officers themselves or their friends or those people that they talk to when campaigning, are likely to have actually experienced issues.

And I guess most of us, when we see other people struggling, want to offer help. But of course, in theory, the thing that’s magical about SUs is that we’re also in a position to warn students so they don’t face things, and crucially, use our good offices and student representation to eradicate those issues in the first place.

What’s the SU theory?

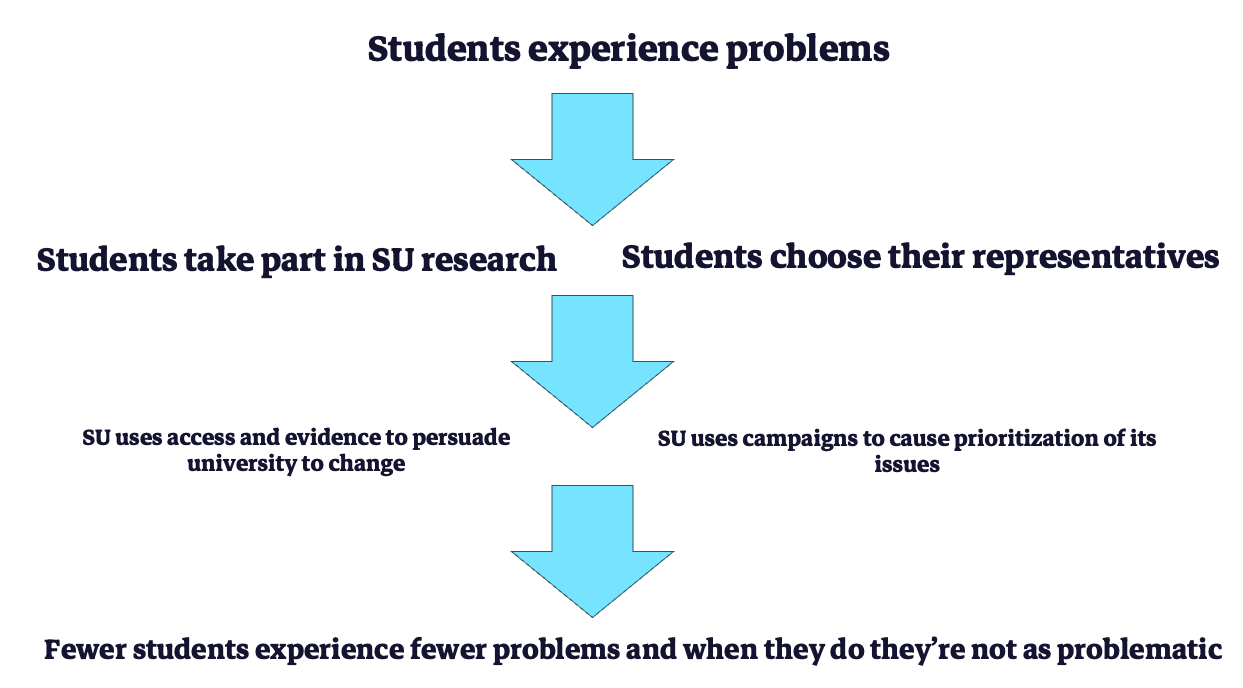

As such, to the extent to which we might regard there being a dominant theory of change in the student movement, a really simple version of that theory of change might be represented by this image.

First, students experience problems.

Then they either take part in SU research, or they choose their representatives at all sorts of different levels, democratically.

Then once all of that has happened, the SU uses its access to decision makers and the evidence it’s gathered to persuade the university to make changes. Alternatively, the SU uses campaigns to cause a kind of public focus on the issues that the union is talking about – and as a result, to cause a prioritisation of those issues on the agenda of decision makers and managers in the university.

If all of that works, fewer students experience fewer problems, and when they do, those problems aren’t as problematic.

But what if that theory of change doesn’t work? What if, over the next three, four or five years, or perhaps, if we’re honest, over the past two or three, that theory of change has started to become harder to use and deploy successfully?

What if, when a student officer presents all the right arguments and all the right research with all of the democratic legitimacy that comes from a high turnout – what if the university still says no?

What if, in an environment where there’s very little money and to the extent to which there is strategic thinking or strategic capacity available to senior managers, it seems to be dominated by concerns of recruitment rather than experience and retention?

What if, when a university is so focussed on recruitment and reputation, that public campaigning becomes impossibly incompatible with being funded by a block grant?

What if that dominant theory of change underpinning student representation in the student movement no longer works?

Shoe-in

I’ve been thinking a lot about this over this summer, partly because my sense is that the student officers I’ve had the pleasure of delivering training to this summer are as energetic, enthusiastic and optimistic as I’ve seen in the almost three decades that I’ve been doing this sort of work.

That’s exciting, but it’s also potentially heartbreaking given the strategic and financial context that the higher education sector finds itself in.

But I’ve also been thinking about it for another reason. I overuse this story, but many people will know, not least because a version of this story has appeared on wonkhe.com a number of times over the years.

I’ve been thinking about the 90s, partly because we’ve got a Labour government, partly because Oasis seemed to have reformed, and partly because it was in the mid 90s where the higher education unit of resource – the amount of money that HE can spend on each student – was last at rock bottom.

In my gap year between school and university in the 1990s I travelled and worked. I travelled to Wolverhampton and worked in a shoe shop.

Now, we might argue that working in a shoe shop hasn’t got a lot to do with working in higher education or indeed, students unions, but I do think there’s some interesting lessons to be learned.

Anyone who’s worked in retail will know that being on the tills is not an easy part of the job, partly because from time to time, you will get a customer that “knows their rights”. I remember vividly dealing with customers that would get to the front of the queue who were trying to return a “faulty” a pair of shoes that they’d bought many weeks previously.

Often those returns had obviously been worn. And my instinct was to think, I think those customers are trying it on, not that the shoes were faulty. “I think you’ve just worn them and won a refund”.

But what’s interesting is what would cause me,either to fetch the manager, or for the various weeks where I was the manager, for me to relent and just give a refund.

There was a particular type of customer, a sort of customer that would do two things. One would argue that they knew their rights, even if sometimes their quoting of what counted as consumer protection law in the 1990s sounded a bit off. The second was their ability to cause a bit of a scene, to raise their voice, to, at least in theory, rally other customers in the queue emotionally behind their position.

That mix of the ability to cause a scene and the ability to convince me that it was more rather than less likely that they knew what they were talking about when it came to consumer rights more often than not caused me to issue the refund they wanted.

Most trusted man

Thinking about the 90s has also caused me to think about Martin Lewis.

Most people will be aware of Martin Lewis – he’s the “money saving expert” that pops up on breakfast television and daytime TV. He has a number of podcasts. He’s widely regarded as someone that you can trust – so much so that when polling companies ask who you trust the most, he regularly comes out as Britain’s most trusted man.

What lots of people don’t know is that Martin Lewis also used to be a sabb – he was the General Secretary of LSE SU back in the mid-1990s.

He’s interesting because both at the time when I encountered him and now, he has a theory of change – one that to some extent is radically different from the theory of change that we tend to have in UK students unions.

Take, for example, the moment when last summer, he won an award.

He won an RTS journalism gong for outstanding achievement. It was a good old fashioned speech, the sort of thing you might have seen at any NUS national conference back in the 90s. But there was one particular line that I was struck by. He said:

…engage your viewers in a way that they think they can go to take action to improve their own lives.

I think that’s interesting because he said something similar to me when I met him in the 1990s when I was also a sabb at the time. His democratic structures at LSE were as traditional as they got – a weekly general meeting at which any student could go, but hardly anyone did, would mandate student officers to do things through motions.

Then, if those motions were passed, students would come back the next week and hold those officers to account on the basis of what they had or hadn’t done. Lewis’s frustration was that not all students went to that meeting, and crucially, that there were too many motions and not enough officers to carry them out.

His vow then and his vow now wasn’t to do things for people. His then and his vow now was to put people in a position where they could solve their own problems, where they felt more powerful.

I’ve also been thinking about the late John Offord, a man who worked on FE policy back when we both worked at the National Union of Students many years ago. John would often refer to what he called the “chippy” mature student, often interchanged with the “chippy” PGT.

When he first used those phrases, I remember vividly talking to John about what he meant in the old NUS smoking room. His argument was that when students were a little older, a little wiser, a little more confident, a little busier and a little less likely to just put up with what it was that they were being given – or when perhaps the qualification itself was slightly less important (and when people didn’t pay money to experience it) there was a certain type of student that one would often find in FE who would be just a bit chippy.

Much more assertive, much more likely to kick off when something wasn’t good enough or when something wasn’t right, someone confident enough to challenge you there and then and to your face.

John was really interested in what it would take to cause more students to feel like that, partly because, to some extent, John shared the view of Martin Lewis that not all SUs (certainly in FE) were ever going to be in a position to have the resources, representational access or cultural capital to be able to do everything for students in that part of the tertiary education sector.

Are students consumers?

Of course all of that implies a focus on consumer rights. And one of the things I’ve learned over the years is that when I write the phrase consumer rights on the site, I can usually expect 24 hours of social pile-on from people (principally academics, but others too) who instinctively don’t like the idea that students are consuming their education.

I have some sympathy with that position. It is, of course, not the case that students buy a degree. Students buy the things that if they put the effort into can cause them to get a degree once the work they produce is assessed.

In many ways, the old gym analogy is the right one. You don’t pay your subscription to a gym and automatically get fit. You have to turn up, put the effort in, put the miles in on the treadmill, do the weights, and so on.

You can’t get a refund simply because you don’t end up fit. But it is also the case that if you enrol at a gym, it doesn’t open on the times it says it was supposed to, and all of the equipment is constantly broken, you obviously have been ripped off. You have rights – consumer rights.

Similarly, whilst we like to talk about students as partners in their education, if the toilet roll runs out, whilst it’s really important that students collaborate as partners with academics to produce educational outcomes, it has always seemed to me that what we don’t mean by partner is that if the toilet roll runs out in the university that it’s the student’s job as a partner to nip to Nisa and get a bag of bog roll.

There is a set of theories that underpin the different roles that students might have on campus. Students are partly members of an academic community, but they are also, of course, partly a paying customer. What’s interesting is that the first of those implies a type of power which is really about voice, because what we do when we’re negotiating with other people in a community is we talk to them, exchange views with them, bargain with them, and sometimes vote with them.

Meanwhile when you’re a customer normally, power is exercised through exit – your ability to withdraw your money, your ability to go elsewhere. Your ability to switch provider and so on, is what should, in theory, and often does, cause a provider of goods and services to become more oriented to customers.

Of course, there are problems with both of those theories once you’re in higher education.

Part of the problem with consumer power is that it aligns three roles into a single actor – choose a user and payer. But higher education splits those roles over a long period of time. That disrupts the amount of power available.

It’s also the case that people often pose the idea of being a partner or a consumer as complete opposites. So for example, when the Competition and Markets Authority was writing guidance about students being consumers in the middle of the last decade, there were plenty of people, including influential senior figures in the sector, that were arguing that it would be “bizarre” to treat students as partners when you were giving them consumer rights.

My view, as expressed in pretty much in the first blog I ever wrote on this site, is that they’re not in opposition.

Students are perfectly capable and legally entitled to sometimes be in the role of partner when they’re working with academics to produce educational outcomes, to learn things, but also as consumer, getting the things that they were promised by their institution, partly whether they paid for that or not.

If nothing else, it seems to me that a good holiday maker, when you go on holiday you do need to go down to the beach, have a dip in the pool, and wander around the resort in order to experience and enjoy the holiday.

And it’s obviously not in the gift of a travel agent to guarantee sunshine. But if, when you arrive at the holiday resort, the hotel isn’t built, or the room that you’ve booked is full of cockroaches, it is pretty obvious to me that you are entitled to a refund.

People that go on holiday can be both holiday makers and consumers all at once.

I think that’s important partly because of the old student survey that I often quote at officers over the summer that was carried out a few years ago into why students thought that their experience had gone well or not well.

Sliding doors moments

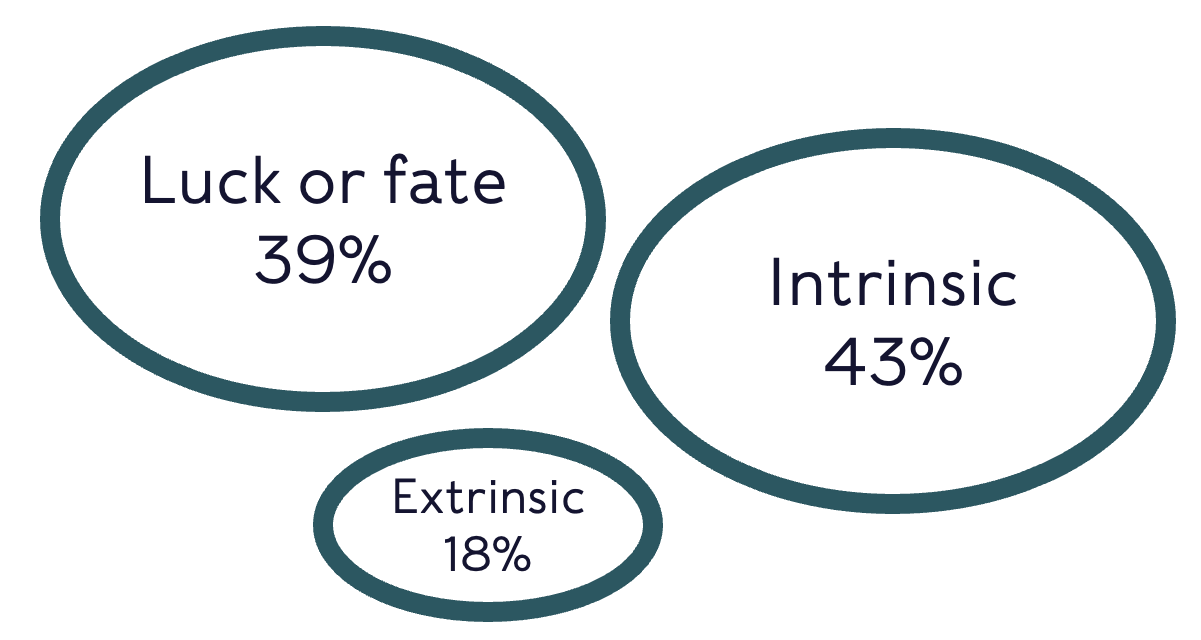

As well as doing the usual quantitative survey responses on whether they were satisfied or not, students were asked why they thought they were satisfied, why they thought they’d done well, and the stats haunt me.

Just under four in 10 gave answers that really related to luck or fate, as if their success or failure was somehow meant to be.

Over four in 10 gave answers that were intrinsic, by which I mean the idea that it was a student agency that caused them to do well or not well. They tried hard. They picked themselves up after a difficulty. They chose the right things. They didn’t put enough effort in, and so on.

This makes lots of sense. Generally, as humans, we want to credit ourselves when we do well in particular. That’s true in a highly individualistic society, and graduation ceremonies do that too. The problem, of course, is that if that becomes the dominant way of thinking, it means that we’re more likely when we don’t do well to blame ourselves too.

What fascinated me at the time, and what fascinates me to this day, is that only two in 10 of the answers that were given were what I often regard as extrinsic things – those that the university policies, systems that the university or the community or the country had in place either to cause a student to do well or not do so well. The student finance policy, the quality of the buildings, the way the timetable worked, and so on.

I think about that a lot. In the context of academic appeals, we know that students making complaints about their provision, their teaching or the services or the buildings that they have enrolled into are actually pretty rare, and they’re even rarer in terms of getting as far as the Office of the Independent Adjudicator in England and Wales, or the courts.

But academic appeals are not rare when a student fails or doesn’t get the grade that they would like. It is pretty common that a student will submit an appeal in order to try and get that grade changed.

Of course, the heartbreaking thing about academic appeals is that the bulk of them fail. They fail because of academic judgment. Students are not really allowed to challenge the judgment made about their marks by academic staff. That is sacrosanct.

What interests me is what students use to justify their appeal. In effect, there’s four categories of academic appeal.

- One is to argue that the judgment itself was somehow faulty or not based on the marking criteria or rubric that was supplied or perhaps carried out with insufficient care and skill. They are fairly rare.

- One is that luck or fate thing – perhaps they had a tragedy or a mental health episode or an illness or some other problem meant that they couldn’t put in the effort that they wanted to.

- Another is backed up with the idea that the student had significant, personal, intrinsic difficulties that prevented them from demonstrating their learning.

Some of those appeals succeed, some fail – although even when they succeed, they often only result in the student being given extra time or an extra attempt at getting the grade that they wanted.

But the other sort of appeal that comes in is where a student doesn’t allocate the responsibility for not doing well to themselves or to luck or fate, but to what I previously called extrinsic factors.

Like where the dissertation supervisor just stopped responding to emails, or where there was never anywhere to sit in the library, or when the PGR supervisor left and no one replaced them, or when the promised personal tutor system in the prospectus didn’t manifest in any way, shape or form.

Often, academic appeals will list a whole raft of factors that students argue caused them, in the end, to not do well. But as any advisor will tell you, 99 out of 100 of those types of appeals fail because the inbuilt systemic assumption is that “they would say that wouldn’t they”.

The official reason given back is “you should have made a complaint at the time”. Of course, what I would argue is that if an institution was learning from its complaints, it would at the very least analyse all of the critiques of the institution or its staff or its services or whatever, whether the appeals had succeeded or not.

I would go further. I would argue that if a student submits an academic appeal based on those extrinsic factors and the university says or decides that that appeal will fail on the basis of academic judgment, the very least it should do is then convert the material that the student has supplied that is about a critique of the institutional failure into a complaint, and investigate that as institutional failure.

Otherwise, all of those failures that students raise just disappear off into the ether. One thing it’s certainly worth checking is that almost every university in the country will produce an annual report for its Senate or Academic board on the nature, type, volume and so on. Of complaints that have come in, there are very few I’ve seen that analyse the critiques of the institution contained in academic appeals that otherwise fail, even if we said to ourselves that of 10 students who submitted an appeal of that sort, five were trying it on.

So one of the things I’ve been thinking about is what might cause a student to complain earlier.

Rights over processes

It is certainly the case that those SUs that have been introducing their course reps not to processes around gathering feedback, but into what it is that the regulator says should be a quality student experience, have started to get some interesting results.

If nothing else, where I’ve been able to spend minutes, and in some cases hours, describing the OfS B conditions in England, there have been long conversations with students about whether the experience they had matched up to those realities.

Similarly, when we convert the NSS questions not into feedback questions at the end, but the idea that they might be promoted as rights at the start, it’s quite interesting to imagine what students might do with those throughout the course of their academic career.

There are also some really interesting implied rights in the OIA good practice framework – its policy notes, which we regularly look at and summarise on the site, can be promoted as sets of rights that students should have – either by student characteristic or by type of course, or indeed by particular issue like placements or student accommodation.

But when I’m on the train back from either officer training or rep conferences thinking about those conversations, I’m often thinking about something much more fundamental.

Student representation is the idea that you’re in a room with other people making suggestions and feeding back. It’s fundamentally a process that was designed around the idea of enhancement, the idea that what you’re raising is optional, an idea for improvement that will be delivered and could might be delivered if there’s the money and the time.

That’s a real challenge when there’s less money and less time. But it’s also a real challenge because it suggests that what is being talked about, the ideas for improvement, are about things that are fundamentally, basically fine.

And the thing about a university having no money and no time and an ever more diverse group of students is that it’s less likely that what a student will experience will be fine or at the minimum standard.

And everything we know about that difference between partners and consumers suggests that it would be weird and faulty to say to a student to say to a person in the queue trying to get a refund on their pair of brogues that they should talk to their shoe rep. That makes no sense whatsoever. In those circumstances, it’s crucial that the individual consumer understands their rights and is able to assert for the minimums.

In other words, student representation, as we generally understand it, from course rep level all the way to central university committees, is only really suitable for improvement and enhancement work. It doesn’t really work for basic rights as such.

Take, for example, industrial action. In theory, pretty much every SU in the country should have been able to take many of the materials that were on offer, not least from this website, and go to their institution and threaten a collective complaint or legal action to get refunds.

But very few students joined those sorts of schemes. Very few students made individual complaints, and very few SUs raised the stakes in the way that I describe. In other words, where large numbers of students are experiencing something below the minimum, it feels odd and uncomfortable for an SU – which to some extent depends on a constructive relationship with its institution for funding – to then get into the adversarial sort of position that the woman in the queue would often get into when I worked in the shoe shop in the mid 90s.

It doesn’t seem like it’s something that would work – and there are good reasons for this.

Passivism rules

In the business schools, the people that talk about consumers and consumer protection will argue about different types of people – and one of the things that’s taught is the idea that people can be what’s called passivists.

Passivists engage minimally when they’re dissatisfied when issues arise, like delays or discrepancies. Passivists often don’t notice or choose not to act. They might express mild dissatisfaction to their friends and family, but they generally don’t take significant action in relation to their experiences.

And the theory goes that the reason for that is five key factors.

- One is opportunity costs, raising an issue and going through formal processes, challenging a big business can take a lot of time.

- Second, lots of people just have an aversion to conflict. They don’t like the idea of getting into a battle with anyone, let alone a big corporate business.

- The third is about confidence and a mixture of cultural and social capital. Some people are just more up for the fight. Some people are more likely to have a broad, or at least basic understanding of their rights. Some people are just in a better position to assert their rights.

- The fourth is the idea that many people, in many settings, will fear retribution in future service delivery. In other words, if you’re being treated by a doctor over a long period of time, and there’s not a lot of sense that you would be able to switch that doctor if you made a complaint, the fact that you’re being treated badly or rudely, or in some cases, worse, might cause you to think that getting into a row with the NHS or the doctor isn’t worth the hassle because they then might stop treating you or treat you very badly.

Remaining passive is quite a rational thing to do, because standing up for your rights involves immediate costs like social discord or time, and there are uncertain benefits – the effort required to complain often outweighs the potential value of any remedial action, and so you end up with what the business schools would call widespread rational apathy,

But this is where Ben Edelman becomes interesting.

Edelman was a Harvard Business School professor who ordered some takeout from a restaurant. He noticed a $4 overcharge on his receipt compared to the online menu prices.

He complained via the restaurant’s website and email, and the owner responded, explaining that the online menu was outdated, but the restaurant menu prices were accurate.

The owner didn’t offer any compensation for the overcharge, and so what Edelman did was demand $12 in compensation, by citing a local consumer protection law in that state that trebled damages for unfair practices.

When the owner refused, Edelman went to the press and submitted a complaint with the relevant regulator, and that story reached local media, where Edelman’s actions were largely mocked as petty.

But when they were mocking him for being petty, they missed something important.

They failed to recognize the really important public service that Edelman had provided by deterring other businesses from overcharging. It wasn’t really worth him complaining for the $12 – but it kind of was worth it, given the impact he had both on that business and many others who might have been tempted to leave older, cheaper menus online.

Edelman is known in some of the textbooks as a nudnik.

The rise of the nudniks

Nudnik is a term that comes from Yiddish and roughly translates to a boar, a nag, a jerk, a busy body or a pest.

A nudnik is an active consumer who consistently pursues action when their transactional expectations are violated, even in minor cases, and the definition of one includes two traits, being an active consumer and acting despite a cost benefit analysis suggesting it may not be worth it for them.

So what are nudniks like? Nudniks possess unique values and innate personality traits that distinguish them from typical consumers, clients or users.

Psychology tells us that some individuals are naturally more eager to complain, whilst others dislike it. Serial complainers tend to be more assertive, aggressive, or highly committed to principles like the belief that promises should be kept.

Some nudniks are driven by spite feeling disrespected when receiving an inferior service, and economically, nudniks have an idiosyncratic utility function, making actions like fighting a minor overcharge seem rational to them, even though it wouldn’t be.

But what they do is the interesting part.

Another example of a nudnik is a man called Hassan Syed, a Chicago businessman. Back in 2013 British Airways lost Syed’s father’s luggage en route to Paris. He tweeted “don’t fly with British Airways. They can’t keep track of your luggage”.

That tweet went viral, but not in the traditional way. Syed purchased Twitter advertising to ensure that his tweet went viral, an approach that then ensured it did, and an approach that was then picked up by media businesses all around the world.

Syed paid Twitter just $1,000 to broadcast his tweet, but because 70,000 potential British Airways consumers saw it, there was mass media attention.

A word was even invented for this – complaintvertising. And it led to British Airways locating the luggage, delivering it to its dad in Paris and issuing a public apology. Syed declared victory. British Airways suffered substantial losses, and the incident is now studied endlessly by marketing professionals.

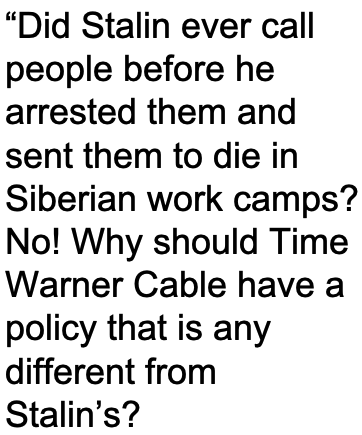

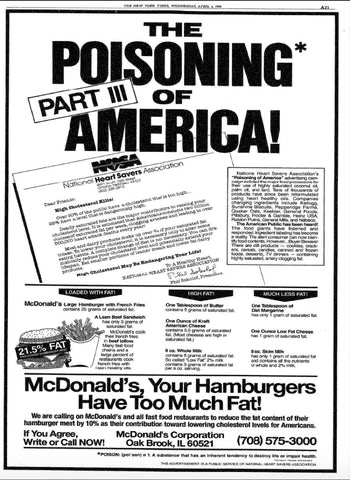

Another example is a comedian called Eugene Merman, who used similar tactics as Syed to air his grievances against a cable TV company in America for missing two installation appointments. Merman disseminated his complaint by purchasing a full page advert in the New York Times. In the advert, he mocked Time Warner Cable’s policy of not notifying customers about rescheduled appointments, comparing it to Stalin’s oppression. He also generated both a resolution for himself and for lots of other people too.

Another example is a man called Phil Sokoloff who, in the 70s, invested money not on social media, but by taking out adverts in his local newspaper about fast food companies using too much fat. His campaign is widely regarded as one that successfully influenced public opinion and led to changes in restaurant products in the decade.

When people face a problem with a service, they can face an action or no action decision. And the truth is that most people act privately by not buying the service again to avoid confrontation, but a small minority of people publicly confront the organisation and they seek redress from the company or air their grievances outside.

This public airing of grievances carried out by these characters called nudniks generates positive spillovers by informing others and influencing their decisions. Nudniks escalate complaints and exit even in concentrated markets. They prompt sellers to introspect and improve their policies.

They facilitate sanctions. Nudniks often sue or use social media to expose misconduct, creating public records and reputational deterrence. Nudniks are more likely to make complaints with regulators, even when it doesn’t result in direct benefits, helping inform better regulation and warning other consumers and nudniks contributes significantly to online reviews and other peer to peer channels which inform and influence customer decisions.

By all accounts, reading the academic papers, it looks like right now, it’s nudniks that have the most power as consumers over businesses, because rthey threaten reputation. And while “exit” isn’t really something most students can use in HE, what we know is that reputation – both personal and institutional – really matters in our sector,

Agency and identity

It’s not just me that thinks that nudniks have got a role to play in higher education.

The widely respected Rille Raaper’s book on Student Identity and Political Agency argues that the UK’s HE system exemplifies quite extreme consumerist policies.

Raaper notes that higher education academics often reject the consumerism model because it conflicts with traditional academic values and expectations for student engagement. But Raaper also argues that student complaints and legal cases can be a real source of power and positions some students as nudniks – who exercise agency through consumer rights, often publicly, and have a reputational impact on universities.

Naturally, because just as the majority of people are passivists, the majority of students are passivists. So if you, like me, think that nudniks might have a role to play in solving problems for students, the question is, who do you pick to try to turn them into nudniks?

The most obvious answer is to argue that officers and reps might be ideal nudniks. They already have a high profile with students. When they choose their representatives, students expect a level of bravery. In theory, you can get them into a position where they know what they can raise, what not to raise, and often when standing for election, student representatives tend to argue that they are “on students’ side”.

But there’s a problem, and that problem, crucially, is that, in my experience, the majority of officers and representatives tend to be passivists too.

Remember, passivists tend not to like conflict. They tend to avoid it or putting themselves in conflict positions.

They don’t make complaints because they’re short on time. We know officers are very busy, and reps are too, and they’re averse to conflict. I know plenty of officers and reps who are just as averse to conflict as the passivists.

One of the offshoot impacts of it being more possible these days to win an election without previous significant prior student representative experience is that some of the confidence and cultural social capital that might have been expected of a full time elected officer 20 years ago isn’t present now.

There’s also, of course, fear of retribution – although this time that fear of retribution, but particularly in an SU context, it’s often framed as worrying that the block grant will either be cut or will no longer be paid.

It might be the case that there are some officers that both could and should become nudniks, or perhaps that most officer teams at least should position one or two of those officers as the nudniks in the team that others can apologise for, but deploy in order to make things happen for students by going public on social media or by encouraging students to make formal legal complaints.

So that winds us back to students. Can we grow nudniks in the student body?

Giving students confidence

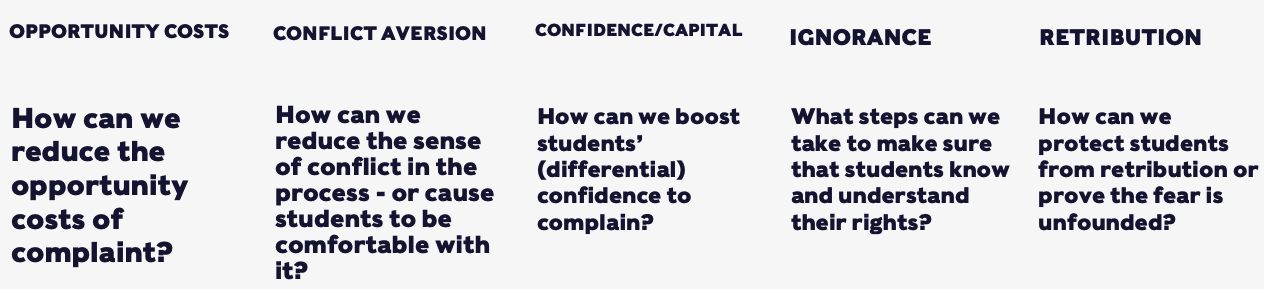

It seems to me that it would be a really helpful exercise for most SUs to sit down and ask themselves five questions.

- How might we reduce the opportunity costs of complaint for students?

- How can we reduce the sense of conflict in the process, or at least cause students to become more comfortable with it?

- How can we boost students’ differential confidence to complain?

- How can we protect students from retribution or prove the fear is unfounded?

Certainly, those previous three questions seem to me to be incredibly incredibly important if we think about international postgraduate taught students – the opportunity costs when you’re only here for a year are potentially huge, few international students will want to get into a conflict with their institution (particularly with their institution looks and sounds like an arm of the state when it comes to their immigration status), it’s significantly less likely that international students will know and understand their rights when they’re trying to navigate a completely new education system, and it is definitely the case that plenty of international are likely to fear retribution.

There is a fifth barrier and question – though that might be more straightforward to solve.

What steps can we take to make sure that students know and understand their rights?

There’s plenty of interesting practice in this space.

He’s on about those bus trips again

In the Netherlands a few years ago, SUs got together through one of their two national unions to produce a National Student Rights portal that they got sponsored by the government.

A few years back in Lithuania, the National Union produced for distribution to students a document called students rights and warranties, declaring their rights in many contexts.

Many SU websites in Scandinavia will have a button to press or a link to click which explains their rights – this series of videos from Linnaeus union in Sweden emphasises the rights that students have over what might be regarded as quite small issues.

This video from Malmo is even more interesting because it’s a collaboration between the university and the SU to make sure that students understand their rights – because the central institution isn’t confident that its authority and its management structure alone will ensure that students’ rights are upheld. It deliberately collaborated with the union to cause students to be able to raise things up with their academics, as well as down through policies and edicts.

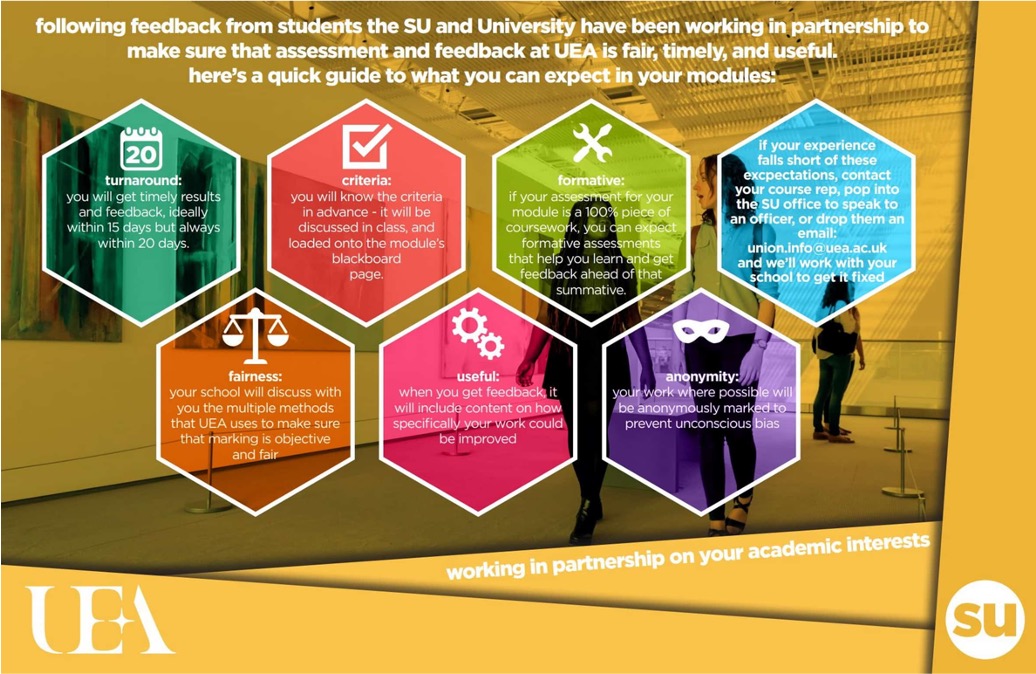

I myself had a run at this back when I was a CEO of the SU of UEA. A huge PVC banner was attached to the wall in the cafe bar that sought to tell students about their rights when it came to assessment and feedback.

We never did get around to evaluating it properly, but what I can guarantee is that there was many a time when I was sat in that cafe bar where students were talking about the content of the poster, and from time to time, would talk about how they were going to go off and see an academic or a head of year about trying to get their feedback processes improved.

And they certainly weren’t all course reps.

Rights matter. But rights only matter if representative organisations like SUs take action over them.

Sometimes we’re defending rights. We’re trying to make sure they’re not taken away.

Sometimes we’re extending them by making something longer or faster or quicker.

Sometimes the role of an SU is to help a student to be able to enforce their rights. That’s in some ways, the bread and butter and advice centre.

Sometimes, SUs have engaged in rights discovery, finding things out that they didn’t know that students had the right to by diving into a long forgotten policy, or by looking at a piece of legislation in a new way.

And sometimes SUs are establishing rights, taking something that was a favour or something that was nice to have and making sure that it’s always there – taking the seven microwaves bought for the SU at the end of the year by a bit of spare budget from the registrar into a permanent right to have your food warmed up on campus, ensconced in a healthy eating policy.

All of those are fraught with challenge. Many of them are difficult. Some of them involve a theory of change, which is becoming harder and harder to argue works.

This one simple trick

But there’s one other rights tactic that’s really quite simple, and I’m not suggesting that by deploying it, every single student will then use their rights – but I think I probably am suggesting that if every SU tripled its efforts to use this particular tactic, then it would be much more likely to inspire a new generation of nudniks prepared to use and enforce their rights.

And it’s dead simple. It’s the sort of thing that Martin Lewis, the money saving expert, does every day. Because, as well as defending, extending, enforcing, discovering and establishing, the other thing I think SUs should do every day, every hour, in every speech, in every conversation, in every tweet, in every Instagram post and in every Twitter thread, is promote to students what their rights are.

Mine the policies, reverse engineer the NSS, look again at the things that are in the B Conditions or the QAA quality code – point out to students what it is that they should be experiencing as a right.

Some of them might even join the queue and cause a fuss.