Ever since I took my now six year-old to Binley Mega Chippy for his birthday, I’ve been trying to get into and understand short-form video hosting service and meme amplification app TikTok.

It’s taken several train journeys and a considerable amount of Ibuprofen, but last night when I saw an incongruous and jarring ad for a deodorant company, I think I realised why I’m so… uncomfortable when using it.

There are lots of people on TikTok talking about their lives, dancing in their houses or parks or schools, making jokes about their relationships and offering advice on how to do things. But few of them are like “me”.

I’ve tried messing with the famous “algorithm” with multiple new accounts to see if it’s just about what I’ve been watching rather than flicking away, and I’m fairly confident now – it’s fundamentally an age thing – not in that “old man can’t program a video” sort of way, but in a “these people are talking to eachother” sort of way. As such the incongruous ad – which was fundamentally 15 seconds of content about deodorant rather than 15 seconds of a normal person doing a normal thing – was quite a relief.

That said, where I’ve found clusters of students using the platform, I’ve found it enormously helpful. That’s partly about surface level stuff – language and slang and “trends” – and partly about developing a deeper understanding of the way in which students are experiencing Covid, higher education, marketisation, the culture wars and now the cost of living crisis. Because I’m being drawn into their world, in much the same way that I am when talking to SU officers, I’m caused to understand it better.

Culture clash

I was thinking about that a few weeks ago when a Black student officer was talking to me about the experience of “code switching” in whiteness-dominated university structures. If you’re not familiar with the term, it’s used to describe the ways in which a member of an underrepresented group (consciously or unconsciously) adjusts their language, syntax, grammatical structure, behaviour, and appearance to fit into a dominant culture.

In some ways “talking university talk” is what the student movement has been training student officers to do in university meetings for decades. But it’s easy to see how doing so is double labour for student officers of colour who also have to switch into whiteness. And if it results in the people we’re talking to never really understanding the world that students are in, doesn’t it end up being counterproductive?

I say that partly because one of the things I’ve been talking to people about this summer has been the “components of political action” for representatives. That, in a cafe about 25 years ago, got converted into the “apathy staircase”, a device used in all sorts of corners SU and student rep training to describe the sorts of stages to take an audience or a student or a reader or a VC on when trying to persuade them of something.

But underpinning it are five types of material and or five skills that it’s important to consider.

- Welcome to my world is about causing others to immerse in others’ logic – in our case students’, rather than universities’. It concerns an understanding of what people’s lives are like. This is a bit different to stats – it’s more about stories – understanding how people’s day to day experiences fit together and getting insight into why things are the way they are.

- Injustice injection is about identifying the aspects of those experiences that are unacceptable – because they represent a broken promise, or a fundamentally worse experience in comparison than others.

- It’s not just me (or them) is the moment where stats come in – this lifts the personal into something much more important, widespread etc having already secured emotional investment in the tale

- It’s the principle is a relief moment – and about converting those wrongs to rights, and identifying what it is that we think students should be entitled to, the sort of conditions we think should exit to support their learning and success, and the kinds of things we think should be universal rather than for a select few. You can either argue for a minimum (all students should be entitled to X) or an aspiration (we should be the best at X)

- Actions are then doing things to deliver on those beliefs and visions – projects, services, funding, actions, events – whatever it takes to make the belief and vision a reality.

In the apathy staircase, the crucial thing is that the speech, blog, presentation or even just conversation goes in the right order. That’s because the decision maker first needs to be in the world of students, not their own. Then it’s because they need to feel the injustice in the experience to feel motivated. Then they’ll likely agree with the positive vision or belief. Then they’re more likely to support the action – or at least work with us on an alternative.

Do it the other way around – start with “give me x” or “do Y” and often we lose them immediately, and by the time we get to why and the student experiences we’re trying to improve, they’ve switched off altogether.

That model is one I’ve been talking about for ages – because it concerns steps on a path that need to be arranged in the right order. But I had cause to revisit the underpinning theory the other day, and two other things dawned on me. First, you do also need to be able to actually “go there” and communicate vividly in all four ways. And second, when you’re being creative and divergent, you need to be able to branch off into other staircases.

Let’s take each of those in turn.

All you do is talk talk

I talk to a lot of SU officers, the staff that support them, and spend quite a bit of time looking at SU social media and websites. I’d say that vanishingly little of the content is about students per se – it’s almost always about the SU itself and its services, events, reps and projects. In fact I often sense a discomfort about talking about students’ lives outside of highly informal settings.

Off the back of that, it’s hard to hear or see injustices – the sort of thing I was talking about here on the site. That then means it’s also hard to see or hear material about visions or beliefs about that stuff. The actions are projects are there for sure – but we’re uncomfortable about talking about the other three boxes, we have a problem.

Put another way, it’s cool that Fibbleton SU is having a “One World Week”. But without the SU talking about what it’s like to be an international student, how the experience was sold on spending time with other cultures but isn’t like that, how the union believes in the rich diversity of the student body and wants everyone to experience other cultures, the “One World Week” project just sits there – like the climactic scenes of a movie without all the exposition and story build up.

So it’s partly about confidence and comms – partly about what we say and when we say it and how we say it. But I think it’s often also about creativity and divergent thinking.

I look like all you need

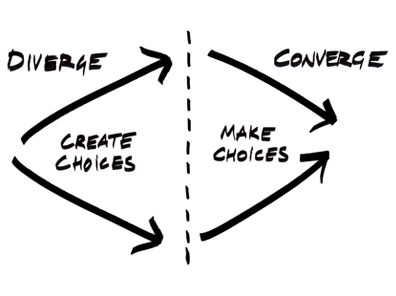

In any conversation, we’re often indulging in convergent thinking – narrowing down, merging options, picking the biggest issues and crucially focussing on plans and actions. But with pressures on us these days, the need to deliver to the strategic plan and get things ready for Welcome, we’re more often than not engaged in divergent thinking – exploring options, possibilities, learning new things and creating ideas.

I absolutely understand why we do that. But it worries me. And it worries me more that daft or problematic manifesto objectives that staff talk to officers about can often be sidelined or ignored or simplistically challenged”, rather than positively explored.

On one level if we take a sentence in a manifesto like “I believe students should be supported so they are never accused of cheating unless they’ve done it deliberately”, I can fill in the boxes – the experience of being a new student, the injustice of nobody telling me the rules, the vision in the quote and the project of a new online module in academic offences for which I’m on a working group.

But that’s the linear, convergent thing. In divergent thinking, I had options:

- In the experience part I could have explored all sorts of other aspects of what it’s like to be a student who is international or first in family. Maybe there are other important aspects to those experiences I’m missing. Let’s talk about them.

- In the injustice stage I could have picked out the overall quality of the study skills support, or the way in which allegations of cheating are handled, or the fact that black and brown international students are disproportionately represented in allegations.

- In the vision stage I had options too – I could have gone for better rights for students to study support, or a vision of academic staff understanding the education systems that their students come from so they know how to handle the transition better.

- And there are always options on actions.

Or take a manifesto promise of “more scholarships for international students”. Knowing that such scholarships are really just sticker price discounts on high tuition fees, I could just think “well that won’t happen” and leave the officer to it. Or I could:

- In the experience part, talk to international student officers about how they got to the UK and what motivated them and acted as barriers during the process

- Explore the way in which courses are “sold” to international students by agents and identify aspects of that that are problematic or misleading

- Identify framing scholarships as a “merit” issue as a misleading thing that unfairly targets international students’ sense of academic worth when compared to the way such intellectual capability and potential is ignored on arrival

- Create visions and beliefs around fair and ethical sales by agents, an experience where no international student is surprised by costs and is given financial support to succeed if times get tough, and devent support for converting academic potential to attainment

- I now have multiple options for actions, all without ignoring the manifesto – we could work on researching the experiences students have of working with agents and fixing them, work on a “solidarity” international student hardship fund generated from a fixed % contribution from their fees (which is really how home domiciled bursaries work), and campaign for better study skills and academic system transition support for international students – a genuine offer related to education rather than the pretence of a “merit” scholarship.

The point is that when SU officers and the staff that support them explore each of the four components rather than tick or close them off, possibilities expand. We can find new and better goals, develop more confidence in communicating about each of the stages, find new insights into the way our members live their lives and just generally for better for them.

Back of the net

Sometimes, you see, manifesto goals are rubbish. They’re the wrong option delivering on the wrong ambition arising from the wrong injustice drawn out of a misunderstanding of the experience.

But even though going to Binley Mega Chippy when I live in Watford was a stupid idea, once I explored it with Benjamin I saw that our family situation means he doesn’t get to go out much on trips or visits, he was very excited to leave the house, dead keen on exploring a local area, amazed that he could be in the place that was the focus of a meme and thrilled that he would have a cool story to take back to his friends at school in September.

Maybe in truth the singing in the car and the winning of the jackpot at the arcades and the staying in a “grand hotel” were really the actions that made the difference for him – but I’d never have known if I’d have just refused, conveniently forgotten or just driven him there and driven him back for a disappointing bag of chips from a bang average chippy on the edge of Coventry.