Strategic plans in students’ unions are a complete waste of time.

About seven years ago now, we presented a session at what was then the annual NUS sabbatical and senior managers summer conference where we argued that strategic plans were a great example of something that everyone thought was important, but was in fact outdated, irrelevant and wasteful – and potentially actively harmful to the interests of students.

We never got round to writing up the session until now. But on the Wonkhe SUs trip to the Baltics, we kept finding excellent SUs without a grand strategic plan. How? Looking back at the slides we presented seven years ago, not only is there nothing in there that we would disagree with today, we think the operating situation that SUs now find themselves in suggests an even stronger case for getting rid of SU strategic plans.

It wasn’t always this way

SUs, just like the wider education and voluntary sectors, haven’t always had strategic plans. A glance through the old Association of Managers in SUs AGENDA magazine archive suggests that some of the bigger unions were trying them out in the 90s and 00s, but the real growth came when everyone had to register with the Charity Commission, got themselves a Trustee Board and retitled their “General Manager” to Chief Executive. Suddenly, everyone had to have a strategic plan too.

In fact, the “strategic plan” has been the single most popular import from corporate management and governance into the voluntary sector – so it’s little wonder that SUs, keen to professionalise the scrutiny over their senior staff and avoid some of the financial calamities common in the 90s and 00s, adopted them wholesale. Today it’s virtually impossible to look at an advert for SU CEO that doesn’t discuss delivering, refining or creating a “bold” or “ambitious” new strategy, and ads for external trustees bang on about strategic plans too. But they’ve all but been abandoned now by the private sector, and the more creative and progressive charities are binning them off too. We think that SUs – radical, creative and member driven – ought to be at the front of that change, not behind.

Love Is a battlefield

The origins of the strategic plan are militaristic. On the battlefield, the past was a good predictor of the future – and there were years or decades between meaningful shifts in basic variables, such as the power of a soldier’s weapons or the range of aircraft. Back then, good data was scarce and hard to come by. Scouts and spies had to risk their lives to find and relay information, and had to be ever on the lookout for enemy deception. Lines of communication were unreliable at best. So small numbers of clear directives, set out in advance, were a tactical imperative.

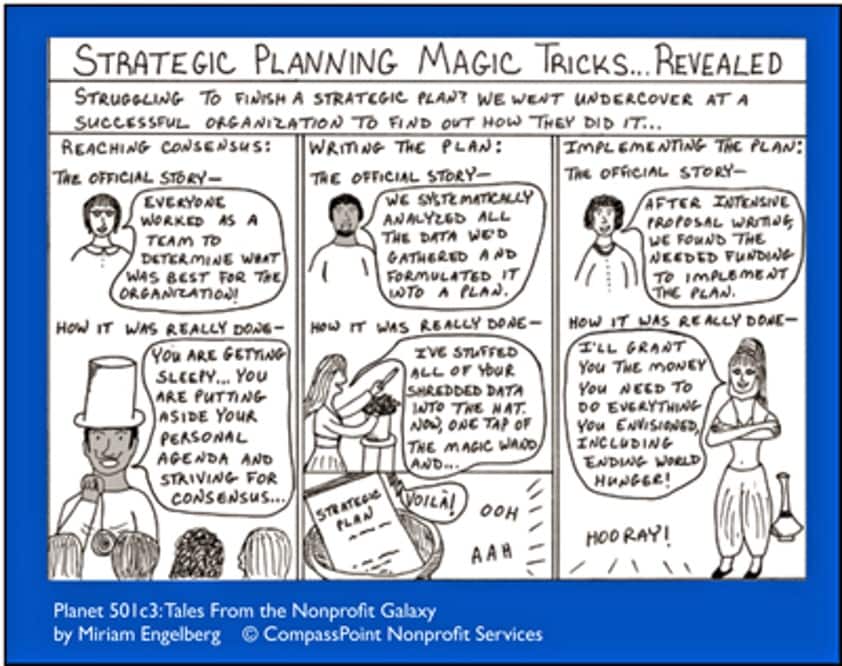

The contexts and the world have changed, but strategic planning hasn’t – much. You identify purpose (mission). Establish a vision. Select goals to work toward mission and vision. Identify specific approaches (or strategies) that must be implemented to reach each goal. Identify specific actions plans to implement each strategy. Compile it into a plan document. And you monitor implementation of it and update it as you go. Easy.

But over the years we’ve identified so many problems with it as an approach for SUs – especially now in the operating context that UK SUs find themselves in – that we think it’s time to stop, and do something more useful instead.

99 problems

The first problem is that planning when you’re running services is very different to planning when you’re an influencing organisation. Look at any sabbatical officer’s leaving speech and you’ll see that most of the wins and achievements were about responding to the unexpected – grabbing at opportunities, or fending off threats. Responding is different to planning to grow your service user base over 3 years, and we should admit that.

Many of the objectives we have in SUs are tied deeply into the politics of our universities. As such, almost every SU we know has three or four “secret” objectives that relate to university departments or senior university people that are never in the strategic plan. We should admit that too, at least to the board.

We can think of plenty of SUs where a three year plan is looked at intensely in year 0, a bit in year 1 and by year three is laughably out of date. It means that intense discussions – which of ten involve researching the needs and wants of the student body and involving students in options – sometimes happen only every three or five years. Shouldn’t we be going through those sorts of processes every year?

The strategic plan is an import from the voluntary sector, but in truth most SUs are multiple types of organisation all in one. The “best practice” planning regime you might need for a retail outlet is very different to that of a societies development operation, and different again to that of a lobbying organisation. It means that much of our planning is a square peg in a round hole, which isn’t helpful for staff, officers, volunteers or members.

Many of the plans we see have cost a lot of money if you add in the external and internal inputs required, but they all seem in the end to be the same. The truth is that there isn’t a whole lot of innovation out there. Notwithstanding sensible conversations of characteristic and social make up, why are we all spending our members’ money to come to the same conclusions? Is that wise in a decade where money will be tight?

Over the years, they’ve usually been used to strategically plan services and infrastructure – but the representational or campaigning goals of the union have tended to be “for the officers”. We know why that “split” has been there, but we do think it’s dangerous. Some of the goals in officer manifestos are hardy perennials. If we’ve thrown serious expertise and resource at services and infrastructure, but let the “amateurs” restart their campaigns every year over a flipchart exercise in August, no wonder it took the student movement 15 years to get anywhere on mental health.

Sure there are upsides

We’ve also seen some real downsides. Sometimes, we’ve seen them used as a tool to stop democratically elected officers from doing things (because, you know, it’s not in the strategy). Often, we know that there is a need to be seen to include every part of the union in the plan so that every staff member, officer and volunteer is happy – even when some areas might be best left to coast along. They all focus on what SUs can control and deliver rather than influence – which doesn’t really match with delivering on the interests of students. And they never really influence resource allocation, even though we pretend they do.

The targets in them make us laugh. We say things like “we will improve participation by 170%”, or “we will improve the balance sheet”, or “we will achieve 90% in Q26”. But we don’t say that we will reduce coursework return and feedback time to three days, or secure a campus ombudsperson for complaints, or win the right to challenge academic judgment in our institution. Nor do we say we’ll work with the community to improve job opportunities for students and locals. So often, our goals are about our organisations rather than our members.

It means we see the same flaws – over and over again. Very few plans actually refer to finances, let alone direct our members’ money. We confuse objectives with methods constantly. There’s a really poor focus on analytic capacity, relationships and being able to respond to changes in the external environment. And so often, as we say above, they’re plans whose ambition is for the organisation rather than its members.

Fair enough

We get it though. Strategic plans sound like the right thing to do to new senior managers and bewildered new external trustees. For CEOs, it can make us look and sound “worth” the salary we’re being paid – when in truth it’s not really the thing that matters. In some unions, some of the processes feel fun and more inclusive because they’re not as divisive or off-puttingly “political” as things like motions or union councils – you can build in things like subtlety and complexity when resolutionary politics can’t.

They’re good because you can (at least officially) get officers and staff on the same page. You can use the process to talk about values and priorities – because you don’t, usually. It allows senior people time to think, and the process sometimes can be used as a way of tackling hidden problems in behaviours, board conflict, or financial management. Passively aggressively, but at least they’re being tackled.

Boards like them too, because at least it’s something to get involved in – rather than just rubber stamping the papers or asking narky questions about the management accounts. And done right, they can give all sorts of people a sense of a “stake” in the organisation because they see their bit, their contribution in the grand plan.

But none of that means we should keep them. And all of those upsides could be done in a different and better way.

Do something different

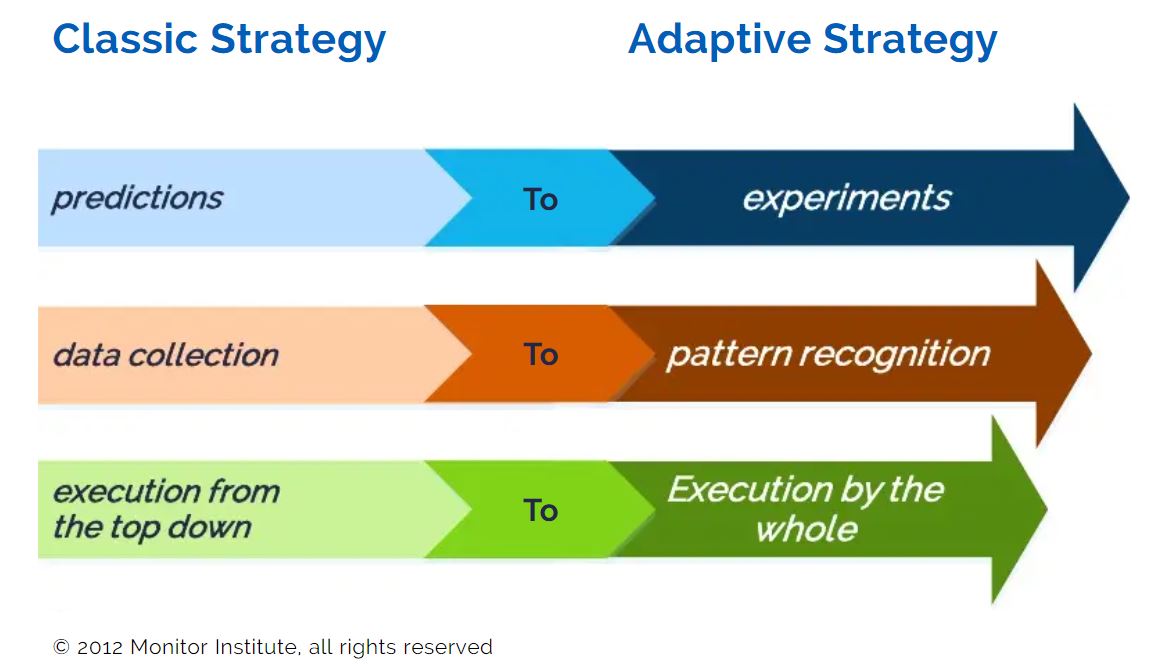

Other organisations are doing things differently. In one model we like, the “predictions” we make in classic strategy change to a focus on innovative experiments. How often has an SU done a democracy review by planning it all out based on research, rather than just trying out a new thing on one department or one officer role?

In that model, data collection shifts to pattern recognition. The idea here is that it’s synthesis and analysis that really matters. Are we reaching peak “data collection” on our members, and is there more we can do to get under the skin of the numbers and generate new insights from them?

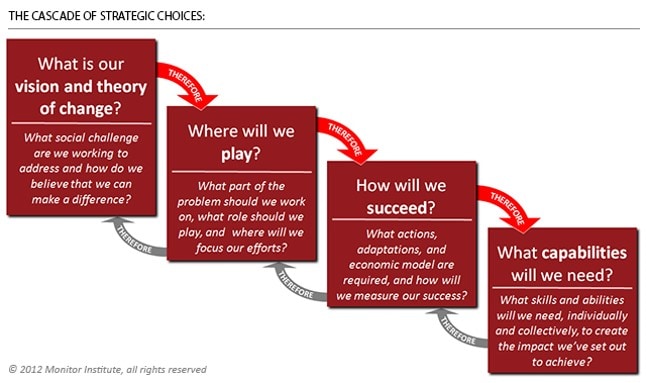

It’s also a model that focuses on execution by the whole, not from the top down. If people broadly share the values and know the big goals, can’t we let them respond and innovate and plan their actions themselves – with the level of student involvement that makes sense for that function? Why must there be a “plan”, signed off by the board, where everything “cascades”?

A similar model we’ve seen builds in the ability to respond – vital right now in HE. It values the setting of long term ambitions (for the organisation and its beneficiaries), allows some annual (or more frequent) stock taking by theme, and fuses in bits of horizon scanning, data analysis and dedicated time and money for creativity, innovation and expectation. There’s a rolling long term strategy, and a one year plan. But not a “strategic plan”.

Some influencing organisations have what’s called a capacity plan. For us that would mean saying “this is a vehicle for students to do things”, “our strategy is about developing capacity to assist them”, and “we need skills and capabilities to respond”. For other organisations, we like what’s called an alignment model. A planning group outlines the organisation’s mission, programs, resources, and needed support; identifies what’s working well and what needs adjustment; and identifies how these adjustments should be made. All without pretending that that work has to be a component of a grand plan.

Adaptive leadership

We also think that new ways of doing strategy needs much more adaptive types of leadership. Instead of seeing CEOs and senior managers as “the ones with experience” (which can feel like “the ones with no new ideas that will stop me”) and the ones that can “develop and deliver a strategic plan”, adaptive leaders focus on creative thinking and design thinking to create new solutions when facing problems that require them. They focus on talent and people, not plans. They know that adaptation occurs through experimentation, and they encourage others to embrace and make sense of the whole complexity of their systems.

Instead of being valued because they can compile a strategic plan, they use a process of simultaneous inquiry and listening – they regulate tension to challenge assumptions and mental models, mobilise teams and enable everyone to reach their full potential. Most of us know that the valued skills in SU CEOs are advising officers, reading university politics, handling crises, advising on institutional representation, political horizon scanning and building officer confidence. So why are those skills so hidden and so rarely tested at application?

Students’ unions have come a long way over the past twenty years. Most have transformed, professionalised, got better at delivering outcomes and improved everything from governance to safeguarding. But the next twenty years will not provide the same backdrop, and the next five years bring real financial and social threats to SUs and their members.

More adaptive and responsive strategy, more focus on the threats and opportunities for our members, more external perspectives and alliances, more officer support and more creative forms of collaboration between unions and more honesty about the skills we really need and value in senior staff is probably a good way forward. And it might mean that to make time for all that, we should ditch the next strat plan.

Agree with much of this! It’s long been the case that the ‘plans’ developed by senior leadership teams have little relevance to the students and to all the staff in the organisation doing the work on the ground. My personal opinion is that strategic plans generally are a way of giving an unnecessary position (CEO) something to fill their time with. My professional opinion is that the only time I have witnessed strategic plans play any role for the rest of the organisation, is when they give staff and students nice buzzwords to use to try and hold leadership to… Read more »