For those us that have been working in and around SUs and the issues of sexual harassment and misconduct for some time, the explosion of activism embodied in “Girls Night in” groups and their venues boycotts has been inspiring to see.

But in many ways it’s pretty miserable that it has had to spring up not over education funding, or mental health, or the marketisation of HE or free speech – but instead over a demand for basic safety on a night out.

It’s also remarkable that just over a year ago, the government had the gall to publish a document that was supposed to be about a financial restructuring regime for universities in financial trouble that demanded vice chancellors defund SUs supporting this kind of campaigning:

The funding of student unions should be proportionate and focused on serving the needs of the wider student population rather than subsidising niche activism and campaigns.

Across the week, boycotts in major student towns and cities have taken place with significant press coverage and partnership work emerging between late-night economy owners, Police and Crime Commissioners, local authorities and Police forces.

But what happens when the press move on and the activism on display this week dies down? Are there complexities that need to be resolved? And how might SUs keep up the momentum generated this week?

Venue assessments

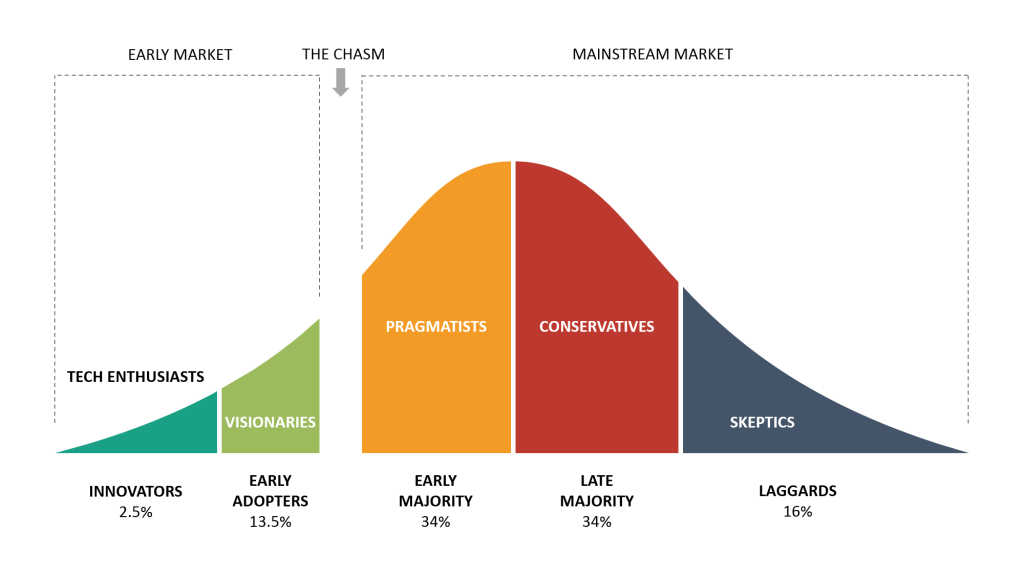

Back in the early part of the 2010, the NUS Women’s Campaign decided to undertake a programme of “Zero Tolerance” audits of venues on a “train the trainer” model. The problem was that the model was ultimately unsustainable – and hit the buffers when venues in the “conservatives” and “sceptics” part of the adoption model refused to play ball.

What might happen this time around? The headlines are that a number of venues and student nights have responded positively to the boycotts abd publicity of the past week or so, with national chain Pryzm particularly keen to be on the right side of the coverage. But we talk a lot at Wonkhe about when “critical” problems have to become “tame” – when activism has to become operational delivery.

Will there be city wide adoption of the demands/standards and how will differences of opinion over them be resolved? When will we know if a given venue has met the standards / demands being adopted – who will give a “green light”? What happens if some venues refuse to play ball? And what happens if a venue says it’s doing something but slips back in a few weeks’ time?

Giving consideration to the operation and scalability of the approach will matter in coming weeks.

From wins to policy

There’s an old story about a group of sabbs being pleased to have secured 31 microwaves from their university for students to heat hot food in. But what happens if one of the microwaves breaks? Is there a policy hook on supporting commuter students or healthy eating that’s written down, agreed and that means the university will replace them if they go kaput?

This matters because while there’s been lots of warm words in recent days, there’s not been so much on policy work.

A few years back now, Kent SU lobbied their local councils (Canterbury and Medway) to change the local licensing policy so that every license holder would have a licensing obligation to actually tackle sexual harassment on their premises. In theory if a premises decides not to comply in making the night time economy safer, they could have their license reviewed and ultimately withdrawn.

The “overton window” is wide open now for an approach like this to be attempted in other big student cities. There’s a blog on the work here and a briefing on the legal stuff here.

Securitisation

One tricky issue surrounds so-called securitization. In many versions of the demands launched locally, the GNI campaigners have been calling for enhanced security measures on the doors of clubs and pubs – searches, body cameras and so on. But is that such a wise idea?

This week drugs charity Release expressed significant concerns in an NUS briefing for SUs that operate venues, arguing that evidence shows that increasing surveillance can actually increase risk and harm:

We would strongly discourage students’ unions and associations… from taking actions that include increasing formal surveillance measures such as the presence of drug sniffer dogs or an increase in the searching of students. These proposals are proven to be ineffective at deterring the consumption/carrying of illicit substances and are found to be harmful in terms of encouraging adaptations (e.g. pre-loading, rapid drug consumption to evade detection), which then results in an increased likelihood of health harms, including overdose – as well as an increased likelihood of criminalisation for people who use drugs.

They also argue that as well as searches for drugs rarely being “successful, evidence suggests that increased searches disproportionately impact students from ethnic minority backgrounds, despite no increased likelihood of drug use, and the presence of sniffer dogs can also cause unnecessarily high levels of anxiety for already marginalised groups.

Security staff

Related to the practices of security staff on the doors of clubs is the issue of training of door staff. Around the country the whispered anecdotal evidence is that there is a national shortage of SIA badged door staff – which is leading both to staff being rostered on that might otherwise have not been deemed appropriate, and some venues having to open with less staff on than they would normally have, rather than the demanded “more”.

The question is whether and how enforcement of already pretty basic standards is going on and what the barriers to that might be. In the NUS and Kent Union examples initial activity included SU volunteers providing training for door staff. But is that a sustainable and long-term solution? And what sort of role should groups like “Good Night Out” play?

Size and shape of the problem

Finally, as we’ve noted on the site before, we don’t have proper, annual, funded prevalence research into sexual misconduct faced by students. Spiking is a really important issue – but understanding the misconduct faced by students in the round is crucial to developing a proper response.

Over ten years after Hidden Marks, we still haven’t seen government or regulators carry out prevalence research – unlike in many other countries including Australia and Ireland. Is this the time for student bodies to push for it?