The Imperfect University: Some people really don’t think much of administrators

Last year I wrote a piece for Times Higher Education on the problem with the term “back office” and the often casual, unthinking use of it in order to identify a large group of staff who play a key role in the effective running of universities but who are the first to be identified for removal or outsourcing in financially challenging times. But what do we mean by the back office?

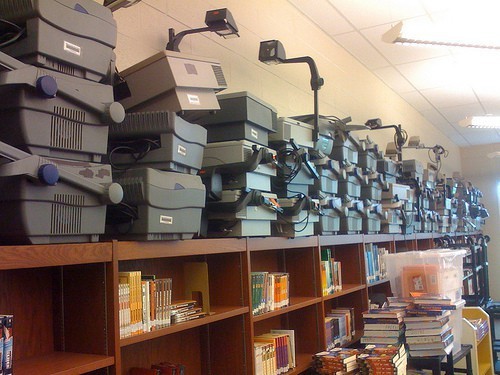

In a university context, it is generally taken to mean those staff who are neither engaged in teaching or research nor involved in face-to-face delivery of services to students. So they might be, for example, working in IT, human resources, finance or student records. Or they might be the people who maintain the grounds, administer research grants or edit the website.

Too often, their somewhat anonymous roles mean that they are treated as third-class citizens in the university context. Because they are out of sight and largely out of mind, most people really don’t know what they do; as a consequence, it becomes much easier for others to write them off and offer them up as the first to be sacrificed when cuts have to be made. Back-office staff do not have an obvious income line and can easily be regarded as expendable. The attitude is resonant of the Victorian view of those “below stairs”. This perception (or lack of perception) is unhelpful, and not terribly good for morale – particularly among those who are so casually dismissed as being “just back office”.

Two recent reports offer a striking example of this. The first is an Ernst & Young report on the “University of the Future” which has found that the current public university model in Australia will prove unviable “in all but a few cases”.

A story in The Australian quotes the report’s author:

“There’s not a single Australian university that can survive to 2025 with its current business model,” says report author Justin Bokor, executive director in Ernst & Young’s education division.

“We’ve seen fundamental structural changes to industries including media, retail and entertainment in recent years – higher education is next.”

The study compared ratios of support staff to academic staff across a selection of 15 institutions and found that 14 out of 15 had more support staff than academic staff. Four of the 15 universities have 50 per cent or more support staff than academic staff, and more than half have at least 20 per cent more support staff.

The report warned that this ratio “will have to change”.

The report, which can be found here, doesn’t give any details on the definition of “support staff”. However, I would guess that it is a sum of all staff who are not academics (the definition of academics can often be unclear too). I must admit though that I’m not surprised that there are more support staff than academics in most institutions simply because of the sheer scale of university operations. I suspect that the variations are largely down to how staff are counted and categorized and differences in physical and organizational structures.

The report, which can be found here, doesn’t give any details on the definition of “support staff”. However, I would guess that it is a sum of all staff who are not academics (the definition of academics can often be unclear too). I must admit though that I’m not surprised that there are more support staff than academics in most institutions simply because of the sheer scale of university operations. I suspect that the variations are largely down to how staff are counted and categorized and differences in physical and organizational structures.

Despite this definitional imprecision, the report’s author is confident in asserting that universities need to cut:

Organisations in other knowledge-based industries, such as professional services firms, typically operate with ratios of support staff to front-line staff of 0.3 to 0.5. That is, 2-3 times as many front-line staff as support staff. Universities may not reach these ratios in 10-15 years, but given the ‘hot breath’ of market forces and declining government funding, education institutions are unlikely to survive with ratios of 1.3, 1.4, 1.5 and beyond.

Leaving aside the fact that many professional staff, for example those involved in student recruitment, careers work, counseling, financial advice, academic support, security and library operations are unequivocally front-line, the idea that the other staff who help the institution function and who support academic staff in their teaching and research are merely unnecessary overheads, ripe for cutting back, is just not credible.

Then from the US we have another report, quoted in the Chronicle. This report, produced by a pair of economists, has identified the ideal ratio of academic staff to administrators needed for universities to run most effectively. It is 3:1 and therefore makes the Ernst and Young proposition look decidedly half-hearted. However, as the article acknowledges, the definitional problems are far from insignificant:

The numbers are fuzzy and inconsistent because universities report their own data. Different institutions categorize jobs differently, and the ways they choose to count positions that blend teaching and administrative duties further complicate the data. When researchers talk about “administrators,” they can never be sure exactly which employees they are including. Sometimes colleges count librarians, for example, as administrators, and sometimes they do not.

Even in the UK, where there is fairly robust collection of staff data by HESA, definitional problems remain. As this earlier post noted there is significant scope for misinterpreting staff data and overstating the growth of the number of managers versus the number of academics working in universities.

These matters are exacerbated in the US for the reasons above and the comments below the piece give an indication of some of the major holes in the economists’ proposition. Nevertheless, the Chronicle finds some willing to support the proposal for an ideal ratio:

Some advocates of increasing the proportion of faculty at universities say they support the researchers’ goal of setting a three-to-one ratio of faculty to administrators.

Benjamin Ginsberg, a professor of political science at the Johns Hopkins University and author of The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matters (Oxford University Press, 2011), has argued that universities would be better off with fewer administrators, people he calls “deanlets.”

The three-to-one ratio “makes a lot of sense,” Mr. Ginsberg said, because it would shift the staff balance in universities. “If an administrator disappeared, no one would notice for a year or two,” he said. “They would assume they were all on retreat, whereas a missing professor is noticed right away.”

Richard Vedder, director of the Center for College Affordability and Productivity and a professor of economics at Ohio University, said shifting the balance back toward faculty is key to keeping universities’ missions focused on teaching, as opposed to becoming too focused on other activities, like business development or sustainability efforts.

“We need to get back to basics,” said Mr. Vedder. The basics are “teaching and research,” he said, “and we need to incentivize leaders of the universities to get rid of anything that’s outside of that.”

This is just ridiculous rhetoric and really we should just discount it. However, such views are, unfortunately, not that uncommon and do have to be challenged.

In order for the academic staff to deliver on their core responsibilities for teaching and research it is essential that all the services they and the university need are delivered efficiently and effectively. There is not much point in hiring a world-leading scholar if she has to do her all her own photocopying, spend a day a week on the ‘phone trying to sort out tax issues or cut the grass outside the office every month because there aren’t any other staff to do this work. These services are required and staff are needed to do this work to ensure academics are not unnecessarily distracted from their primary duties.

Although provision of such services is not in itself sufficient for institutional success, it is hugely important for creating and sustaining an environment where the best-quality teaching and research can be delivered. If a university chooses to dispense with the professional staff who deliver these services in order to pursue a mythical ratio then it might find it’s rather hard to hold on to those outstanding academics for very long.

Most recently there is a piece in THE reporting on the launch of the “Council for the Defence of British Universities” which notes that

The council’s initial 65-strong membership includes 16 peers from the House of Lords plus a number of prominent figures from outside the academy, including the broadcaster Lord Bragg of Wigton and Alan Bennett. Its manifesto calls for universities to be free to pursue research “without regard to its immediate economic benefit” and stresses “the principle of institutional autonomy”. It adds that the “function of managerial and administrative staff is to facilitate teaching and research”.

Now whilst I do of course agree that this is a fundamental part of administrators’ roles and it is splendid that the great and the good do accept that administrators exist, there is something here in the tone of this comment that makes me think that some might take this to be that we should be “seen and not heard”. I do hope not.

Reblogged this on Things I grab, motley collection .

Well done. Much of the criticism of “administrators” in higher education is, as you noted, merely overheated, unsubstantiated rhetoric. The growth of administrative functions in universities is in large part due to the fact that scholars have largely handed over responsibility of running the institution over to these administrators because they “hate meetings” and other dull work that falls outside of their increasingly narrow academic passions. But then they malign these same administrators and treat them as second-class “overhead”. It needs also be said that the design of the scholar’s position encourages them to focus on their own needs, rather… Read more »

Is not the goal of the 3:1 ratio is to outsource all the other services, and so not to get rid of the tasks but to get rid of the direct employment? What would London Met’s ration have been had it gone ahead with the shared services idea?

Reblogged this on Registrarism and commented:

One from earlier this year

What ever the opinion is, it is a clear fact that there is a need to have both the academician and administrator to manage the University functions. What is more important is to find the right balance between the two categories of personnel, not the number and which category they belong.

Came to this from the ‘Apocalypse’ piece. As an administrator in a non-teaching research department, my job is crucial (as in, anyone could do it but it needs doing). I’m not an administrator in the ‘traditional’ University definition but more the general office definition, but without me who’d deal with imaging and websites and other little jobs for one of our multinational research trials? Are you going to outsource that, at greater cost than little ole me? I don’t think anyone would be that stupid. But I’ve spent enough time in academia to know that plenty of commentators have no… Read more »