Little England’s splendid isolation in European HE looks increasingly absurd

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

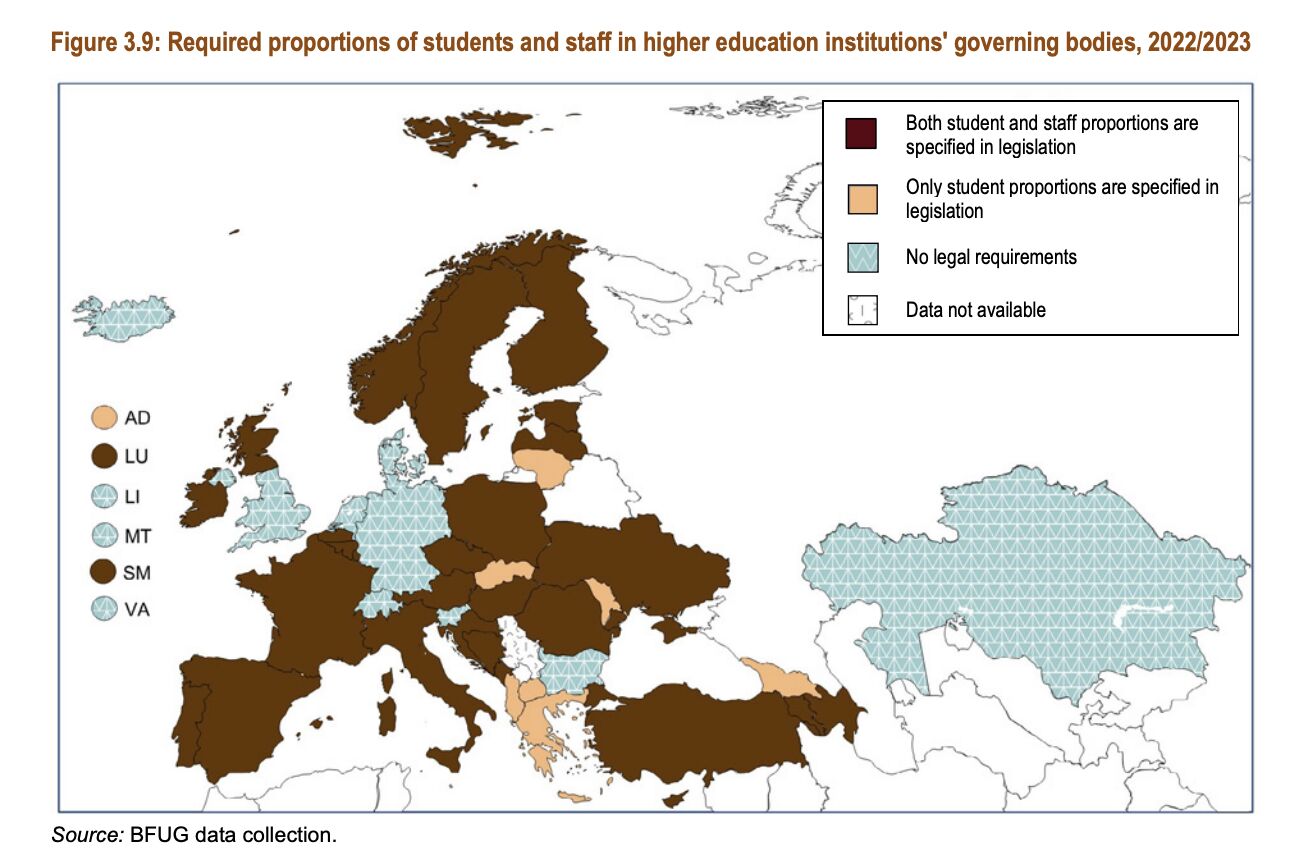

It shows that (other than Scotland), the UK is one of the few countries with no legal requirements for student or staff representation on governing bodies – while most of Europe has mandated both.

Whenever I see a map like this, I instantly wonder whether our exceptionalism might be justified. But on this one, I doubt that “not mandating student or staff participation on governing bodies” could somehow be linked to our system’s reputation or excellence. Quite the opposite, in fact.

The map appears in The European Higher Education Area in 2024, the official Bologna Process Implementation Report that is produced every few years to monitor how the 49 member countries (we stayed in the EHEA despite Brexit) are implementing their ministerial commitments.

The report assesses each country’s progress on the three core commitments in the Bologna process – degree structures and transparency tools, qualifications recognition, and quality assurance – plus newer priorities like fundamental values (academic freedom, institutional autonomy, democratic governance), social dimension (access and participation), learning and teaching quality, and student/staff mobility.

It uses scorecard indicators, comparative data, and visual maps to show which countries are fulfilling their commitments and which aren’t, essentially holding governments accountable to the promises they’ve made and identifying where the EHEA needs to focus improvement efforts – making it awkward when countries like the UK sign communiqués but then appear in red/orange on compliance maps.

It was prepared for the May 2024 Tirana Ministerial Conference, which sadly fell in that gap when the Westminster minister with responsibility for higher education was Luke Hall, Robert Halfon having resigned a few weeks prior. Luke didn’t go.

The rest of the class

Beyond that governance map, the UK’s showing in the report makes for uncomfortable reading across multiple dimensions – because there’s a pattern of signing up to commitments while failing to implement them in practice.

When it came, for example, to developing strategies on the social dimension of higher education, the report found that “almost all countries reported having implemented a social dialogue before the adoption of their strategy, except for Kazakhstan and the United Kingdom.”

That’s quite the peer group we find ourselves in. In policy-making processes more generally, the report finds that associations and networks of higher education institutions, including national rectors’ conferences, are “not usually included” in national higher education policy-making in only four countries – Kazakhstan, Montenegro, San Marino, and the United Kingdom (England, Wales and Northern Ireland).

The mobility data is especially depressing, particularly at doctoral level where the UK registers “below 5 per cent” outward mobility – one of the absolute lowest rates in Europe, comparable only to Turkey. At master’s level it’s the same story, with the report noting that “graduates in the United Kingdom and Türkiye preferred to obtain a degree in their country of origin.”

The report also observes that “97 per cent of UK credit mobility occurs at bachelor level” – suggesting that what little mobility we do have is concentrated in short undergraduate exchanges rather than the deeper engagement at postgraduate level that characterises more mobile systems.

The UK’s National Action Plan for 2024-2027, published following the Tirana conference, is revealing in what it commits to and how. On mobility, the plan commits to “implement and review the UK’s International Education Strategy” with the review described as “underway” and to “continue promotion of education exports and partnerships via the International Education Champion” – which is all about selling UK education abroad rather than supporting UK students to study elsewhere.

Value added

Even on something as seemingly straightforward as the Diploma Supplement – the standardised document that all Bologna countries committed to issuing automatically, free of charge, and in a widely spoken European language – the report notes that in the UK, some institutions issue it, others deliver the Higher Education Achievement Report (HEAR), while others don’t bother with either.

The Lisbon Recognition Convention was adopted by UNESCO and the Council of Europe in 1997 and has been ratified by virtually all Bologna Process countries. It established five core principles based around the idea that holding a qualification at one level in any EHEA country should give you the right to be considered for entry to the next level in any other EHEA country, without having to jump through endless bureaucratic hoops to prove your qualification is valid.

The Implementation Report shows up the countries that have not embedded all principles into national legislation, noting that “Ireland and the United Kingdom (England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland) does not legislate in this area” as institutions:

…have full autonomy over their admissions, and for principles to be specified in national legislation would be considered a violation of autonomy.

The problem with that argument is that Lisbon doesn’t actually threaten institutional autonomy at all – it was explicitly drafted to co-exist with autonomous admissions decisions, not to abolish them. It defines “access” narrowly as a procedural right – the right of qualified candidates to apply and be considered, not a right to be admitted. The “recognise unless substantial difference can be shown” principle requires fair assessment processes, not that institutions lower their standards or abandon selectivity.

The absence of a legal floor for these principles doesn’t create autonomy, it creates opacity – and codifying Lisbon’s procedural guarantees would make the system more predictable for applicants and less legally fragile for providers, all without constraining any meaningful aspect of institutional decision-making.

Quality problems

Writing on Wonkhe back in September, Douglas Blackstock – who is just now stepping down as President of the European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education (ENQA) – set out how England is not compliant with the Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area (the ESG), which represent one of the three core commitments of the Bologna Process.

Meanwhile the fundamental values monitoring bit covers more areas where the UK already looks embarrassing in the Implementation Report – student and staff participation in governance (where we have no legal requirements), institutional autonomy (where we invoke it selectively as an excuse to avoid commitments), academic freedom, and public responsibility for higher education.

A monitoring framework was mandated by ministers in the 2020 Rome Communiqué, which asked the Bologna Follow-up Group to develop a framework for the enhancement of the fundamental values of the EHEA that is set to “assess the degree to which these are honoured and implemented in our systems.”

The methodology will capture both de jure (legal framework) and de facto (actual practice) indicators, with data coming from multiple sources. On that governance representation map we started with, the UK already looks bad – but when you add in the de facto assessment of how institutional autonomy actually works in practice, the gap between claimed autonomy and regulatory reality, the picture is likely to be considerably less flattering.

Middle class jollies

The Westminster government’s approach on mobility also shows up the gap between rhetoric and reality. While agreeing at the January EU-UK summit to work towards Erasmus+ association by the end of the decade (2029-2030), in public it misunderstands what Erasmus+ has become – treating it as a middle class jolly when it’s now a comprehensive framework spanning vocational education, digital transformation, European University Alliances, and inclusion programmes – all while obsessing over “imbalance” concerns that ignore both soft power benefits and the reality that European universities are increasingly competitive.

What makes this particularly daft is that given the problems with skills gaps, teaching innovation challenges, poor credit transfer infrastructure, and the impending credit-based student finance system that will supposedly enable flexible modular study, any sensible Department for Education would be as desperate to get back into Erasmus+ and wider EU educational cooperation programmes as DSIT was to get back into Horizon Europe for research collaboration.

The Bologna Process doesn’t prevent any of the genuine autonomy that matters – the ability of institutions to determine their academic offer, set their research priorities, make their own admissions decisions within agreed principles of fairness and transparency, or govern themselves effectively with appropriate participation from their academic communities.

What it does require is that countries implementing these commitments do so in ways that include democratic participation, maintain quality assurance independence, enable student mobility through portable finance and recognised qualifications, and engage collaboratively with European partners rather than treating international cooperation as an optional extra.

The case for UK non-compliance would need to demonstrate that meeting these commitments would somehow hold us back. But reviewing the evidence in these reports and the commitments in our own National Action Plan, it looks like the opposite is true – as well as leaving Wales and Northern Ireland without proper representation in international forums, and keeping us disengaged from collaborative programmes that could address the skills gaps, innovation challenges and access problems that the government claims to care about.

In 2027, the fundamental values report, the ESG revision, and the next Bologna Implementation Report will all land around the same time – and maps that show the UK in the same category as a handful of outlier states on governance, quality assurance, and mobility won’t be easy to dismiss as European bureaucracy we’re well rid of as they were in the past.

Why does England need a bureacratically state-controlled equivalence for European qualifications? The bureacratic standardisation processes erode the distinctiveness of English higher education and its institutions. It enables commodification of higher education qualifications, which works against the fact that a university is not simply producing and selling another product or service. It also controls higher education as if a government agency, a mere extension of the state and thus reduces the autonomy of the universities. The universities are not quasi-public sector organisations, such an entity only exists as an idea and not as a legal entity in the form of a… Read more »

It’s certainly true that the UK is a legal outlier. But it prompted me to check if this meant UK unis were less representative, but the opposite seems true: the sector’s own CUC Code of Governance effectively fills the gap. The real twist is what happens in countries that do have the legislation. Research shows that de jure rights are often undermined by de facto managerialism. Even with seats on committees, student and staff views can be overruled or “managed” by VCs and senior teams who control the agendas, information flow, and the ‘real’ executive decision-making bodies. It really highlights… Read more »

There are two problems with the analysis of this “97 per cent of UK credit mobility occurs at bachelor level”. Most doctoral programmes in the UK are not credit accumulation programmes. It would therefore be impossible to undertake credit mobility. The other problem is that for most English universities students are made to extend their degree by a year in order to incorporate a mobility period. There is thus no real credit mobility. Students would get their degrees without any credit gained at the host institution as they are not obliged to take the additional year. Scottish institutions mostly operate… Read more »