Who’s ready for a debate at 930am on a Sunday?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

But despite being on the very fringes of the fringe, PLMR’s Policy Hub, hosting a Russell Group SUs panel on “Universities’ Potential in a Mission-Led Government”, was surprisingly packed for a lively canter around the key issues facing the sector.

Favour Alexander Samuel, president of Nottingham University SU, kicked things off with a set of bleak stats and a fairly direct policy ask:

We want government policies that restore faith in the value of university education.

University of Manchester VC Duncan Ivison lamented that Labour had started by claiming it had “some big ideas about higher education” and had made “some brave decisions about tuition fees and signaling a new approach to international students.” But momentum seems to have stalled.

I’m hoping this over the next couple of days, as we hear from the Secretary of State and various ministers, we can get some of that joined up thinking. But for me, that’s what’s missing.

His big point was that higher education is not a market, it’s a system, and policy should reflect that fact. Universities needed to collaborate more – Manchester’s shared mental health services across five universities and joint PhD programmes with FE colleges were examples of what’s possible.

On international students, he was blunt about the “structural problem” in UK HE, where the revenue source is the gap between what it costs to teach and what it costs to do world class research, and the revenue received that is covered by international student fees. His prescription:

First do no harm. Don’t undermine what is already a very fragile system.

Steve O’Neil from UCL’s policy lab came armed with research – two thousand people polled, five focus groups, and some fascinating findings.

Sixty-three per cent say universities have a positive impact. People get the national stuff – training doctors and teachers, but locally, it’s even stronger. Universities are seen as “bringing in skilled graduates,” providing “customers for local businesses,” and crucially, “making places more vibrant.”

But there’s a massive graduate/non-graduate split. Eighty per cent of graduates view universities positively, but it’s only around fifty per cent of non graduates. And among non-graduates, less than half are aware universities even do research.

The polling also revealed some worrying perceptions. People think there are “too many poor quality degrees” and worry specifically about whether degrees “link strongly enough to the workplace” – noting that disappointment in skills development is a key driver of graduate regret.

HEPI’s Nick Hillman used the fringe to take aim at the government’s missions rhetoric.

I have to say, I always thought the missions were an electoral device, and we certainly heard more about them before the election than they seem to have actually been implemented post the election.

He noted “a palpable sense of frustration and disappointment among vice chancellors” at UUK Conference – ministers were, he said,

…delivering the same speeches, in effect, [that] they delivered last year when they were brand new ministers.

On the international student levy specifically, Hillman had a run at hypocrisy:

The government says it’s opposed to tariffs, but this is a tariff on a very important British export industry.

Arguing that UCL would lose £42 million annually, and Manchester £27 million, he also questioned whether international students’ pockets could be reasonably squeezed any further:

I’m not completely sure that expecting international students who are already cross subsidizing our research already cross subsidising the teaching of home students in universities actually have deep enough pockets to also cross subsidise the rest of our education system.

Favour Samuel shared her own story as an international student from South Africa, watching classmates “leave mid-degree” because of the changes to visa regulations and policies. For Favour and friends, the UK was:

…basically telling international students that we want your fees, but not your future.

O’Neil had more surprising polling data. Even among Reform voters, there’s more support than expected.

The more recent reform voters are actually slightly in favour of international students staying to work, which I think would surprise a lot of people.

The Q&A segment was fun. A retired prof asked about Skills England moving from education to the work and pensions departments, warning that the government might “become more prescriptive in deciding what skills they want from where.”

Jane Norman (University of Nottingham VC) attacked the market/choice v central planning issue from a slightly different angle:

“..are we going to lose physics [departments] because individual universities are making market-based decisions? Should there be “some guiding hand, possibly from government or from the Russell Group?”

University of Cumbria academic Erica Lewis – who’s been both the higher education advisor to the Minister for Higher Education, Tertiary Education, Science and Research in Australia and the former leader of Lancaster City Council – was worried about the optics of an ask for money in the context of town-gown tensions; students not putting bins out, taking over housing and clogging buses:

My residents hate the fact that students don’t put their rubbish out properly… Why on earth would you think that it is reasonable to ask for another ten thousand pounds so that you can go to a random university in a random corner of the country… when we have homeless people on the streets?

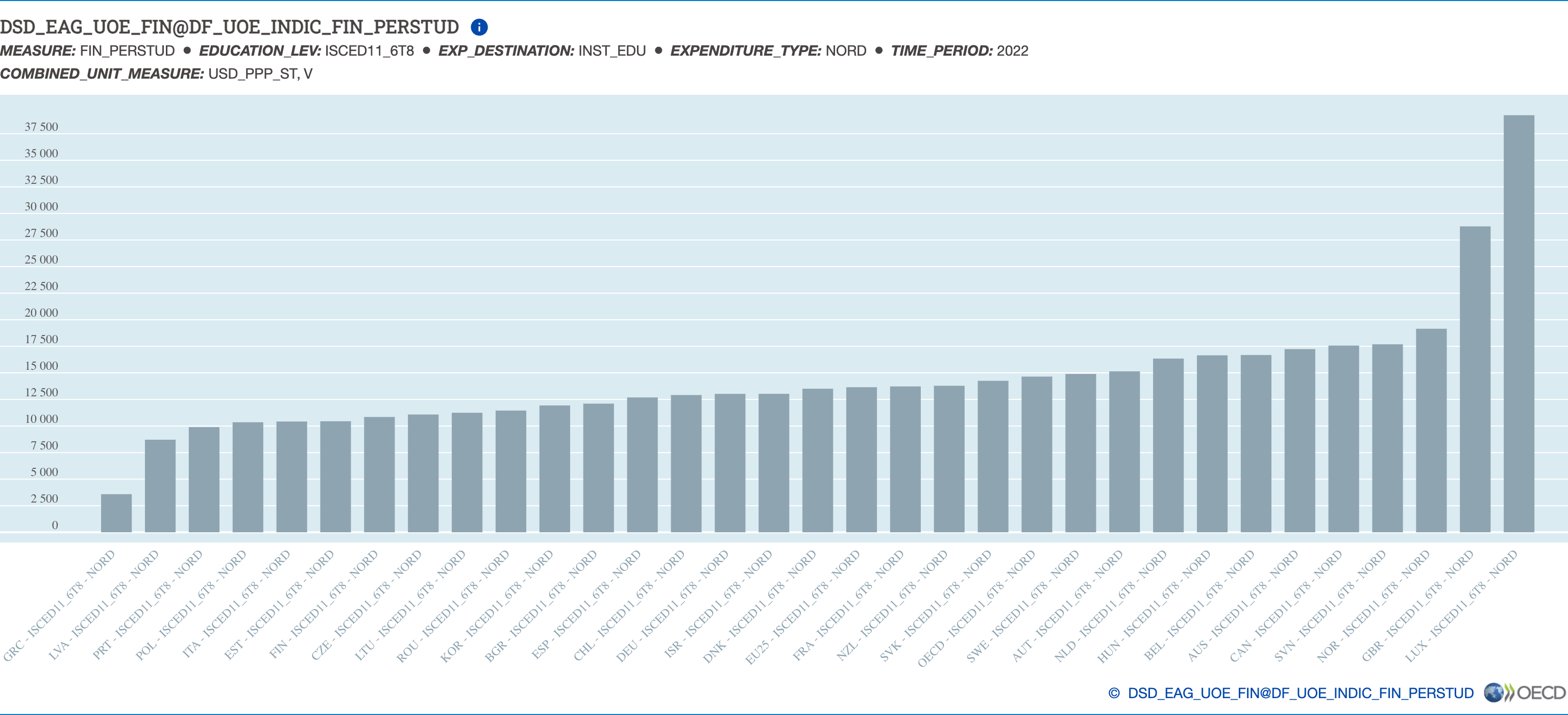

One wag (OK, it was me) chucked a curveball about the recent OECD “Education at a Glance) figures which appear to show that UK full-time expenditure on students is the second most expensive in the OECD.

Do you have a sense of why that is? Do you have a sense of whether or not we could deliver the skills the economy needs in a slightly cheaper way.

Hillman dodged by pointing out that much of the money comes through student loans, and that OECD numbers include research and development spending. The problem is that loaning students costs money in subsidy – and even with R&D stripped out, we look pretty pricey.

Expenditure on educational institutions per full-time equivalent student

More importantly, he noted that “we also expect universities to be a mini welfare state”, but it’s not entirely clear that Erica Lewis was ready to trade a tuition fee reduction for having to provide more for students in every other part of national and local government.

Samuel wrapped up with some takeaways that cut through all the policy complexity:

The current system is unsustainable. We need urgent action. Access and sustainability are linked. You can’t have one without the other, and public trust is a precious or fragile thing. We must address legitimate concerns whilst demonstrating value.

There’s a cracking article in a universities special in Nature this week that points out that right around the world, the trend to increase access to education has placed severe financial burdens on governments, giving policymakers a choice – maintain free (or very low cost) higher education for ever-increasing student numbers, often at the cost of academic quality, or shift the cost on to students and accept a huge private higher-education sector.

That said, it does also point out that both the United States and most European countries maintain a mixed system of vocational and teaching-focused colleges and universities, alongside “Humboldtian-style” flagship universities.

There’s not really any road left in the UK on transferring the cost to graduates, and no money at No 11 for muddling through. Without retreading 1992, if a mass system with less research in it really is one of the ways to achieve sustainability, that does feel like a debate that neither the audience, the panel nor the Labour party feels ready to have.

You have your own answer. The question is not if, but when. The universities are not a high priority for the government. I think it likely that government-led reform can not occur until the next parliament. Until then, the universities must continue to absorb the higher costs and lower revenue.

The thing is, you can’t have a pre-1992 HE sector any more because the FE sector has expanded to fill that vacuum. The FE model, for all its faults, is both cheaper and more aligned to employment skills – if Universities abandon research-informed teaching for skills acquisition then then the only weapon they will have is reputational kudos. Whether that is worth the fees will be tested over time.