I’ve been in Scotland this week with Mack and Alan Roberts from CounterCulture, working with a group of SUs to both reimagine SUs via our New Rules strategy game, and to deliver training on student interest policy and power issues for student leaders.

On Day 1 we started as we often do – exploring some of the harsh realities being faced by students across the sector.

It was, as ever, both eye-opening and bleak – with compounding issues in cost of living, housing, mental health support, teaching and learning and space on campus all adding up to real problems for those that students’ associations represent.

But as the flipchart sheets were being pinned up on the wall, something struck us. Most of issues were familiar to us – we’ve spent the summer in SU meeting rooms with sabbs. But we’re not convinced that many other people know about many of the problems that were highlighted.

The late Nick Berg (the man who, to all intents and purposes, “invented” non-commercial services in SUs) once said to me:

If you say you’re the voice of students – but never say negative things out loud… you’re not, are you?

Just last week on the main site we were discussing iceberg theory – where some things are above the surface – and likely to be dealt with – while usually many are below, which means they won’t be prioritised.

If it’s the case that the increasingly horrifying horror stories that have come to represent the contemporary student experience remain below the surface and not being “voiced”, all of the research suggests that they are much less likely to be tackled by policymakers.

In both conversations with delegates and with each other while waiting for flights home, the question for us was why that’s the case – and what SUs might be able to do about it.

What emerged in our chats was a complex web of individual and institutional pressures that create what we’ve come to think of as a “conspiracy of silence” – not deliberate, but systemic nonetheless.

Secrets and lies

Contemporary academic governance relies heavily on the notion of student voice, but researchers reckon there’s an abundance of student inputs in UK academia, and a dearth of “meaningful” student voice.

Research by Young and Jerome suggests that UK national policy tends to reduce understandings of “student voice” to a loop where students express feedback, the university takes it on board, and they then (ideally) tell the students how they have responded to their feedback – in fact, those are the three questions on voice in the NSS.

But the closed-loop system flattens complex student experiences into manageable data points, inherently limiting what can be expressed.

The distinction matters a lot. Matthews and Dollinger’s research argues that student representation and student partnership differ and the difference matters – with representation involving students publicly speaking for others versus partnership involving direct, and often confidential, collaboration.

If SUs focus primarily on the collaboration involved in co-production rather than amplifying authentic student experiences, they risk missing the very voices they claim to represent – and failing to build the pressure for change.

Normalisation

One of the most insidious aspects of how silencing works is the process by which extraordinary problems become ordinary realities. As one participant put it:

You have to cope with you. You can’t be miserable about your situation all the time. You’re too hungry and tired. You learn to love your limitations.

The psychological adaptation – what we might call “normalisation drift” – represents a silencing mechanism that then operates both individually and systemically.

At regular intervals over the decades, for example, NUS has produced research on the state of rental accommodation that has variously documented the disgrace that it has become – mould “everywhere, literally everywhere. Just painted over.”

But it’s became mundane, pedestrian and obvious. Students “learn to love their limitations” because the alternative – constant misery about unchangeable circumstances – feels unsustainable.

That normalisation process then operates across organisational levels. What begins as shocking becomes familiar, then invisible. Housing problems that would have generated outrage a decade ago now barely register as newsworthy because they’ve become part of the expected student experience.

The psychological adaptation that allows individuals to cope with difficult circumstances inadvertently contributes to systemic inaction by reducing the urgency that might drive change.

Research confirms the dynamic in broader organisational contexts. Studies of “problem normalisation” in institutional settings show how repeated exposure to negative conditions leads to “desensitisation” where abnormal circumstances become psychologically processed as normal. Others refers to a range of “devious frames” that are used by actors such as denialism (it is not a problem), normalisation (it is normal and expected) and victim blaming (it is a problem because of the individual mistakes) that become “how we operate around here” and thus hard to contravene.

It happens not just to those directly experiencing problems, but to those in positions to address them – university managers, SU staff, student leaders, policymakers – who gradually adjust their expectations downward to match deteriorating realities.

The weight of self-presentation

But we reckon other things might be at play too. International students, for example, can face particularly acute pressures that extend far beyond simple cultural adjustment.

Studies highlight that international students are subject to systems of oppression ingrained in higher education and society, including western supremacy, systemic racism, and neo-racism, with similar dynamics evident in UK contexts.

When universities hold significant power over visa status and future opportunities, public criticism becomes genuinely risky.

The challenges international students face are both systematic and severe. Research identifies language barriers, financial issues, and academic study requirements as primary reasons for dropout, alongside experiences of being “treated really badly” by institutions.

Yet these students often remain silent about their experiences, caught between the need for institutional support and fear of jeopardising their precarious status.

Social media then compounds the pressures through what research identifies as carefully managed self-presentation. Studies of college students in the US suggest that online self-presentation changes significantly during transitions to college, as students face the need to reclaim or redefine themselves in the new environment.

The platforms students now use most – LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook – are structured around positive self-promotion. Research shows that students selectively use privacy settings to control their online self-disclosure and primarily use public platforms to maintain image rather than to voice complaints or problems – which tend to be relegated to semi-closed settings like WhatsApp groups.

This creates what researchers call “impression management anxiety.” Studies show that US college students actively adjust their disclosures according to the strict audience whom they valued the most, meaning authentic expressions of struggle get filtered out in favour of curated success narratives.

When someone’s landlord paints over mould that returns weeks later, sharing a photo feels like admitting failure rather than exposing a systemic problem.

The competitive nature of higher education then intensifies these pressures. In an environment where students compete for graduate opportunities, internships, and future employment, appearing to struggle with basic issues like housing or welfare can feel like signalling weakness or a “negative/troublemaker” attitude to future employers or academic references.

It creates what economists call a “collective action problem” – individually rational behaviour (staying quiet about problems) produces collectively irrational outcomes (problems don’t get addressed).

Student housing provides a good example of how serious problems remain below the surface whilst simultaneously becoming normalised as “just how things are.”

The scale of the crisis is staggering – NUS research shows that one third of students are struggling to pay housing costs, with 84 per cent of students having experienced issues in their housing – including almost half with mould or mildew.

But despite all the shocking statistics, housing problems rarely generate sustained public attention. Students are taking drastic action to cope with the rising cost of rent, including illegally doubling up in rooms and turning to “buy now, pay later” financing agreements to pay the rent.

And the human impact is severe – 17 per cent of students struggling with housing costs are resorting to foodbanks, whilst over 40 per cent of working students work at least 20 hours a week – often missing substantial contact hours as access to housing comes at a cost to their education.

It represents exactly the kind of material that should drive urgent policy intervention, but it remains largely invisible in mainstream discourse. Individual students experiencing these conditions face the classic problem – acknowledging housing problems can feel like personal failure in a competitive environment where everyone is supposed to be thriving.

But there’s also evidence of systematic normalisation at work. The fact that students working 20+ hours a week whilst studying full-time has become unremarkable speaks to how dramatically expectations have shifted. What would once have been considered educationally destructive is now processed as normal student behaviour, reducing the sense of urgency about addressing underlying causes.

The partnership paradox

So why the silence from SUs? Students’ unions operate within their own web of constraints that discourage authentic voice.

Universities have become increasingly dependent on student satisfaction metrics and reputation management. The system of procuring student voice operates as a feedback loop where metrics, at best, can measure the distance between expectation and delivery, but not quality. It reduces complex experiences to simple satisfaction scores, inherently limiting what can be meaningfully expressed.

Financial pressures compound the constraints. With many universities facing deficits and increased reliance on international student fees, there’s institutional pressure to maintain positive narratives. SUs, usually financially dependent on their universities, find themselves caught between representing student experiences authentically and maintaining crucial institutional relationships.

But’s not just the political economy that SUs operate in. One revealing aspect of how silencing works institutionally emerged in our conversations around campaign strategy. As one participant noted:

Anything like housing or cost of living – you really don’t want a specific objective. You need to expose the issue and then get people… don’t try and give a tidy solution. The campaign should be ‘what the f*** are you gonna do about this?’ as opposed to ‘do this about this.’

That exposes a crucial flaw in how many of the boilerplate consultancies approach campaigning. Standard SMART objectives frameworks – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound – break down when confronting genuinely systemic problems.

The “A” for “Achievable” becomes a silencing mechanism because truly addressing housing costs, maintenance inadequacy, or institutional racism doesn’t feel achievable within typical campaign timescales or union resources. See also the “winnable” after widely felt and deeply felt.

Faced with that constraint, we know that SUs often nudge themselves into smaller, more manageable objectives that feel “SMART” but don’t address the underlying issues students actually face.

It creates a systematic bias towards incremental changes rather than surfacing the scale of problems that might demand more fundamental responses. The framework itself becomes complicit in keeping the most serious issues below the surface.

Instead, campaigns on wicked problems could focus on exposure rather than solution. The goal could be making visible what currently remains hidden, forcing those with power to acknowledge realities they’d prefer to ignore, and asking uncomfortable questions rather than proposing neat answers.

Wins and work vs people and issues

On Day 1 we also discussed another institutional silencing mechanism – the way in which professional communications defaults to what we might call “wins and work” rather than “people and issues”:

Comms professionals do wins and work. LinkedIn is all wins and work. Nigel Farage is very good at people and issues.

This distinction runs like this. “Wins and work” communication focuses on what the organisation has achieved, what activities it’s undertaken, what successes it can claim. It’s fundamentally promotional – designed to enhance organisational reputation and demonstrate competence.

“People and issues” communication, by contrast, focuses on what’s happening to the people the organisation represents and what problems need addressing.

The gravitational pull towards “wins and work” is understandable from an organisational perspective. It’s safer, more positive, easier to measure, and aligns with institutional pressures for reputation management. But it systematically privileges organisational interests over authentic representation.

When SUs spend more time talking about their events and services than the issues that students want to see addressed, they inadvertently participate in making those problems invisible.

Research on organisational communication confirms the dynamic. Studies show that public-facing communications from representative organisations increasingly focus on “activity” rather than “outcomes” or “issues,” partly because activities are more controllable than results and less controversial than problems.

But the shift has the unintended consequence of reducing public awareness of the very issues the organisations exist to address.

The comparison to Nigel Farage is uncomfortable. Whatever you think of his politics, Farage understands that political attention follows what gets articulated publicly. His willingness to “say things out loud” – particularly uncomfortable or controversial things – generates the kind of attention that forces responses from those in power.

Meanwhile, organisations focused on maintaining respectability and demonstrating competence often fail to generate equivalent urgency around the issues they claim to care about.

The media and information environment

The broader information environment then compounds these silencing effects through what researchers call “attention economics.”

Local journalism has been severely depleted, with many outlets now dependent on press releases rather than investigative reporting. Even well-researched reports struggle for coverage when they’re “all stats, no stories” – exactly the format that housing research and student experience data typically takes.

Meanwhile, social media algorithms prioritise engagement over accuracy, and the most popular platforms amongst the young reward aspirational content over authentic struggle. Research on college students’ social media use reveals that platforms are used primarily for identity development involving impression management, social comparison, and self-concept clarifying, rather than for surfacing systematic problems.

That, too, creates a systematic bias in what kinds of stories become visible. Personal success narratives, institutional achievements, and positive developments get algorithmic amplification, whilst problems, failures, and systemic issues get filtered out.

The result is an information environment that makes it appear as though serious problems are less prevalent than they actually are, reducing the pressure for addressing them.

The competitive nature of higher education also creates perverse incentives at every level. Universities compete for students, rankings, and reputation, making public acknowledgement of systemic problems feel like competitive disadvantage.

As our conversation noted on Day 1, when Dundee University publicly acknowledged significant problems, other Scottish institutions distanced themselves rather than recognising sector-wide issues. The instinct was to go “we’re not like that” rather than “these issues aren’t unique to one institution.”

Students face similar competitive pressures. In an environment where graduates compete for employment and opportunities, appearing to struggle with basic issues can feel like signalling weakness to future employers or academic references. This creates what our conversation identified as a collective action problem – individual rational behaviour (staying quiet about problems) produces collectively irrational outcomes (problems don’t get addressed).

Research on organisational silence reveals several mechanisms that extend well beyond higher education. “Employee silence” – the withholding of ideas, concerns, or feedback – operates through multiple channels – fear of negative consequences, lack of confidence that speaking up will make a difference, and social conformity pressures.

In higher education contexts, these mechanisms operate across multiple levels simultaneously. Students stay quiet due to competitive pressures and precarious status. SU officers learn to moderate their language due to institutional relationship management. University managers focus on controllable metrics rather than uncomfortable realities. Media outlets prioritise engaging content over systematic investigation.

The result is what organisational researchers call “pluralistic ignorance” – where individuals privately recognise problems but assume others don’t share their concerns, leading to collective inaction. When housing problems, welfare issues, or educational inadequacies remain largely undiscussed publicly, those experiencing them can feel isolated and abnormal rather than recognising shared experiences that might drive collective action.

The silence reinforcement loop

The factors all then create a reinforcement loop that strengthens over time. When problems aren’t discussed publicly, they appear less significant to policymakers and institutional leaders. This lack of attention means resources aren’t allocated to address them, making problems worse.

As problems worsen, the gap between official narratives (student satisfaction, university excellence) and lived reality grows, making it even more difficult for individuals to speak out without appearing to attack the institution they depend on.

The normalisation process compounds the loop. As problems become familiar, they generate less emotional response and feel less urgent. Housing crises become “housing challenges.” Welfare emergencies become “cost of living pressures.” Educational inadequacy becomes “learning experience diversity.” The linguistic softening reflects and reinforces psychological adaptation, making problems simultaneously more tolerable and less likely to be addressed.

For the most vulnerable, it’s all worse. International students face compounded versions of all these pressures whilst also being subject to additional silencing mechanisms. Policy changes have removed international students’ ability to switch to work visas before completing studies and confined family visa rights to postgraduate research students, making their status even more precarious.

It creates what might be called “double silencing” – where the students facing some of the most severe problems are also least able to articulate them publicly. The result is that international student experiences remain largely invisible in public discourse about higher education, despite these students contributing substantially to institutional finances and facing distinctive challenges that affect their educational outcomes.

Breaking the conspiracy of silence

So what’s to be done? Arguably, it requires coordinated action across multiple levels – changes in how SUs operate, how universities approach student voice, how media covers higher education issues, and how students themselves understand their role in institutional accountability.

Most crucially, it requires recognising that authentic representation sometimes means saying uncomfortable things out loud, even when – especially when – doing so challenges institutional narratives of success and satisfaction.

Understanding the dynamics points toward potential solutions. The evidence suggests that direct storytelling and testimonial approaches may be more effective than traditional policy documents or statistical reports. When students can tell their stories directly, without institutional filtering, different kinds of truth become possible.

It aligns with what our conversation participants suggested about simple approaches – recording 15-second videos showing student realities, asking “what are you going to do about this?” rather than presenting neat solutions.

Social media presents both challenges and opportunities. While platforms reward aspirational content, they also offer ways to reach audiences directly without institutional gatekeeping. Research shows that 83 per cent of students aged 16-24 use social media for academic purposes, suggesting potential for different kinds of engagement. The key may be creating spaces where authentic experiences can be shared without individual students bearing the full cost of speaking out.

But arguably the most important shift needed is cultural – recognising that critical voices can be helpful rather than threatening, that exposing problems early is better than managing crises later, and that authentic representation sometimes requires abandoning the comfortable focus on “wins and work” in favour of the more challenging territory of “people and issues.”

For SUs specifically, it suggests several strategic shifts.

- First, moving away from SMART objectives when confronting systemic problems, instead focusing campaigns on exposure and forcing responses rather than proposing solutions.

- Second, rebalancing communications from “wins and work” towards “people and issues,” even when this feels less comfortable or controllable.

- Third, creating spaces and mechanisms that allow authentic student experiences to be shared without individuals bearing disproportionate costs for speaking out. This might involve anonymous testimony platforms, collective story-sharing approaches, or structural support for students willing to speak publicly about difficult experiences.

- Fourth, recognising that there should be two entries on the risk register. University-union relationships, whilst important, shouldn’t become a silencing mechanism. When maintaining institutional relationships becomes important to keep the grant rolling in, SUs also risk losing their essential function as independent student voice.

Finally, SUs arguably need to develop comfort with uncertainty and conflict rather than retreating into the safer territory of manageable activities and measurable outcomes. The most important issues affecting students – housing, welfare, educational quality, institutional racism – are inherently “wicked problems” that resist simple solutions but nonetheless require sustained attention and pressure.

Until we can shift the incentives that push toward silence, the most serious problems facing students will remain exactly where they are – known to everyone, spoken about by no one, and therefore unlikely to change.

The iceberg theory suggests that what remains below the surface won’t get attention. In higher education, we’ve created systems where the most urgent student experiences are almost guaranteed to stay submerged, not because they’re secrets, but because all the pressures – individual, institutional, and systemic – align to keep them quiet.

Props to Brunel SU

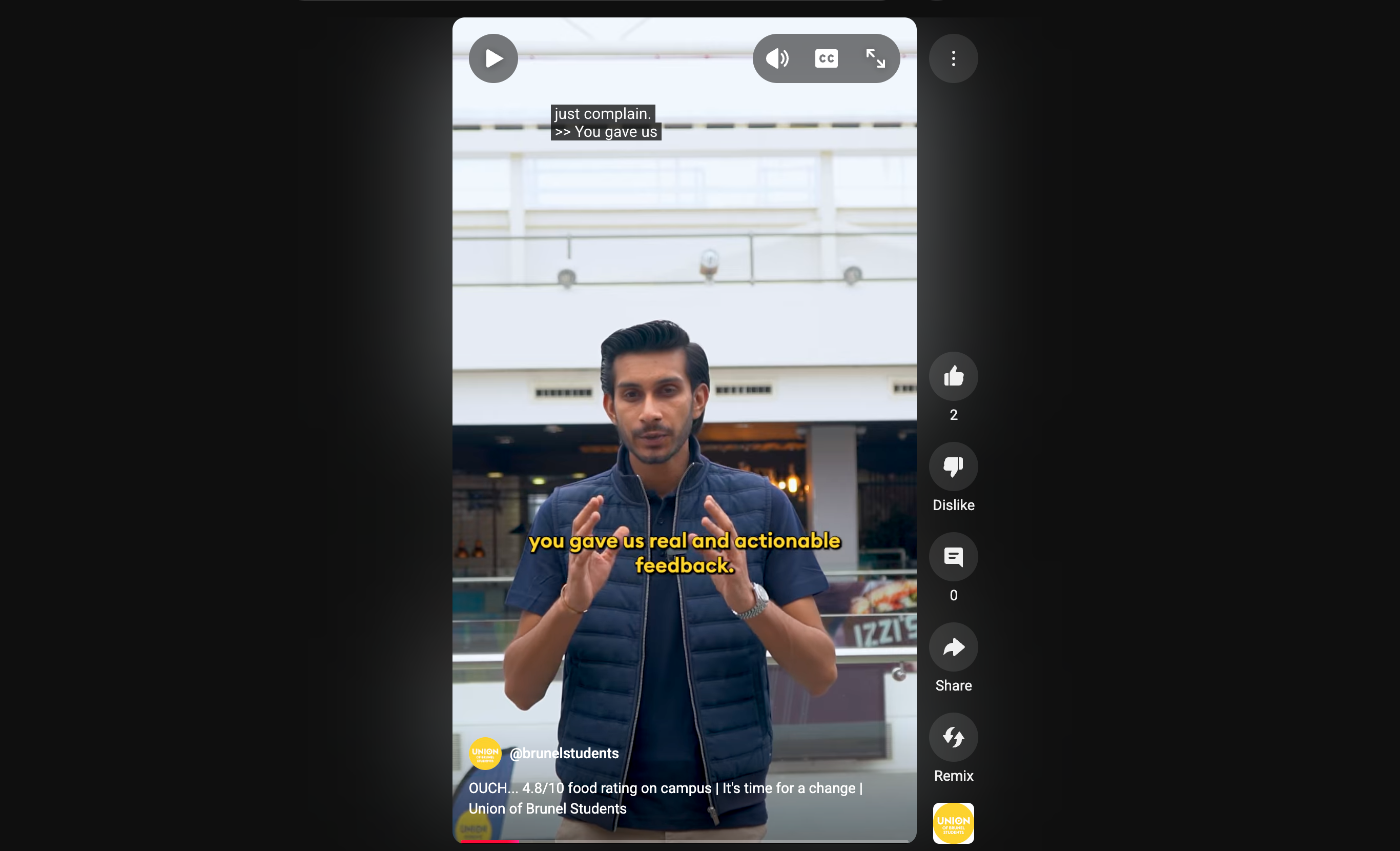

Just as we were finishing up, a bit of doomscrolling brought some inspiration.

Rather than celebrating the fact they conducted a food survey, in this video Brunel SU leads with the uncomfortable truth –

4.8 out of 10. That was the average food rating on campus. Not great.

They’re doing “people and issues” rather than “wins and work” – starting with student experiences rather than organisational activities.

What’s also striking is their willingness to surface problems without offering neat solutions. They took student feedback:

…straight to Chartwells, the unis catering provider, they listened, but no commitments yet. Change with big companies is slow, but we are not backing down.

This is exactly the “what the f*** are you gonna do about this?” approach our participants identified – exposing issues, applying pressure, and being honest about the lack of progress rather than presenting manageable wins.

It demonstrates that authentic student voice can coexist with institutional relationships, but requires SUs to prioritise truth-telling over reputation management. When problems stay visible and unresolved, they’re more likely to eventually get addressed than when they’re diplomatically managed into invisibility.

As the Berg might have said about the Berg – if you say you’re the voice of students, and find a way to say the negative things they are experiencing out loud, you really are.