In recent years there’s been a tendency in the UK to adopt a relatively defeatist position on student volunteering with their students’ union.

There’s good reasons for that – students are working longer hours than ever before, they often live much further from campus, and many have caring or family responsibilities that the less diverse student cohorts of the past didn’t.

And of course a large volume of members of SUs these days are international PGTs – studying for a single year in an unfamiliar country isn’t especially amenable to slowly building your confidence to taking on a position of responsibility.

But there’s no getting away from it. Every time we visit a European country on one of our study tours, we usually find large numbers of student volunteers and few staff – and often these students are just as economically precarious (if not more so) positions than students find themselves in the UK.

The downsides of a culture in which we do more for students – both in universities and students’ unions – than they do for themselves are multiple, not least in the way they prevent students from experiencing and learning from positions of responsibility that are valuable for their career but also, across multiple countries, for the future of their country.

It means that in the seminar rooms we meet in and the campus tours and canteens we visit, one question is never far from the minds of those of us from the UK – how on earth do they do all of this on so little resource and so few staff?

These are important questions – not because we should somehow be ashamed of the level of professionalism that we have reached in our SU work in the UK. They’re important because funding pressures make it almost inevitable that most SUs in the UK will have to become smaller than they have been – and in that context understanding how a more visceral and literal interpretation of “by students, for students” can be made to work becomes crucial.

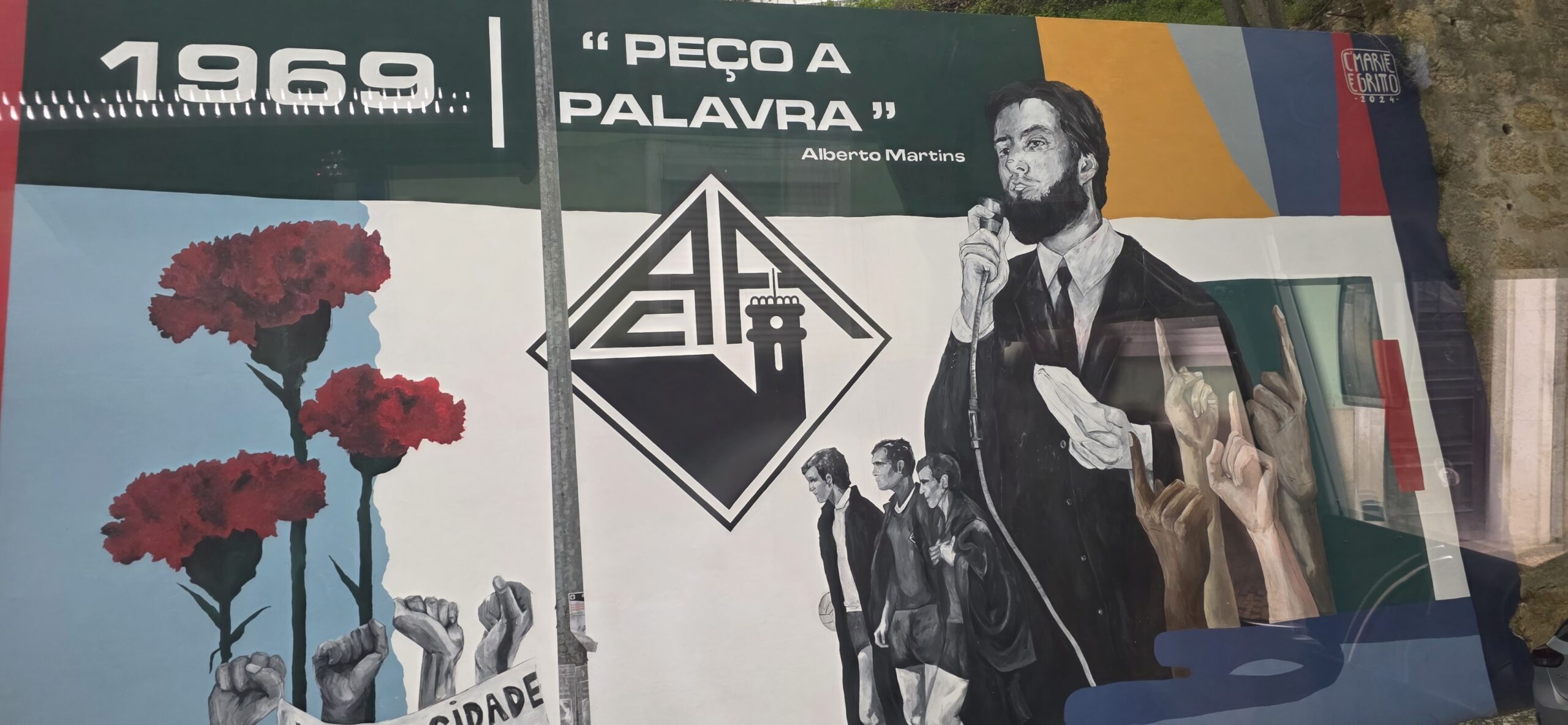

As such, our mini SUs study tour to Portugal this year was hugely instructive – not necessarily because we saw lots of new things (although Praxe, ribbons and the Burning of the Rooster were all fascinating), but because the way the hugely impressive system of student representation and activities suggests a set of scaffolds and practices that provide answers to some of the trickiest questions – all in a context of relatively similar student hardship and economic precarity.

The cone of involvement

In Portugal, our guess is that student volunteering works partly because participation isn’t presented as an all-or-nothing proposition. Instead, what we saw what we might call a “cone of involvement” – a graduated pathway that begins with small, manageable commitments before expanding into deeper engagement.

When we asked all the volunteers we met for their origin stories, their entry points were all deliberately accessible – designed to be so narrow and unintimidating that almost anyone can step through. At one visit, we heard how a casual conversation with a housemate had led to helping with a single project – at another, an open call for “collaborators” had seen someone assist with basic logistics for an event. Initial touchpoints required minimal commitment but provide an essential first experience of contribution.

Students described how their involvement gradually expanded as their confidence grew. One student explained how they’d first attended a workshop organized by AEFCT’s Área de Formação e Empregabilidade (the SU’s careers committee), then volunteered to help at the next one, and eventually joined the planning committee.

Another described starting as part of a “BioBuddies” mentoring program before taking on progressively larger roles within their academic nucleus. That pattern of incremental responsibility appeared consistently across institutions – allowing students to test their capabilities in low-stakes environments before tackling more challenging positions.

The social scaffolding around this progression is interesting. Rather than being expected to navigate the volunteering landscape alone, students benefit from intentional peer guidance. At ISCTE, for example, the dedicated room for academic societies (núcleos) creates a physical space which allows those leading them to hang out, work and exchange ideas. The ongoing proximity to more experienced peers provides both practical support and aspirational modeling.

Similarly, when AAISEC Lisboa’s mission statement describes promoting “educational and integration activities,” it’s acknowledging the essential role of community in nurturing volunteer engagement – each step up the cone feels less daunting when others are taking it alongside you.

The transformation from passive participant to active volunteer to student leader happens through what we might call a “show, then do” approach – students first experience activities as beneficiaries, then contribute in small ways, and eventually take ownership. That’s in contrast to the UK model where volunteer roles often come pre-packaged with substantial responsibility and job descriptions or “volunteer profiles”, creating a barrier to entry that many students understandably find too high to surmount.

What was also clear was how deeply Portugal’s model of student volunteering is intertwined with social connection and emotional fulfillment. The most successful volunteer initiatives we encountered weren’t framed primarily as CV-building opportunities or abstract civic duties, but as pathways to friendship and belonging.

Most of the academic societies we saw run group social mentoring schemes of the sort we’ve talked about a lot on the site – explicitly designed to create personal connections between students immediately, but then linked to the academic society and any other agendas it might have. The connections aren’t incidental to the volunteering process – they’re central to its appeal and sustainability. Students repeatedly told us they initially got involved not because they felt a burning desire to represent their peers, but because they wanted to be where their friends were, doing things that mattered together.

Rewards

In some countries volunteers or committee members are paid, and in some (including in parts of Portugal) engagement (or at least the learning from it) is rewarded with ECTS credit – which helps students find the time to get involved too.

But the special status of student association leaders represents one of the most forward-thinking elements of Portugal’s framework—a system that recognises the commitment of student governance beyond mere extracurricular activity. These aren’t merely discretionary accommodations but legally enshrined rights that recognise the substantial time commitment and professional development involved in leading student organisations.

The framework provides several key protections for these association leaders:

- First, they have the right to justified absences when participating in official association activities. This isn’t simply about attending the occasional meeting—it covers national councils, formal representation duties, and the substantial governance work that maintains student democracy.

- Association leaders also benefit from assessment flexibility—the right to reschedule exams and assessment dates when association duties create unavoidable conflicts. This recognises that student leadership responsibilities often intensify during precisely the same periods as academic pressure points.

- The flexibility extends to academic deadlines, with extensions available in view of leadership responsibilities. This matters particularly during high-intensity periods of student representation—when institutional crises emerge or when strategic planning demands concentrated effort.

- Perhaps most significantly, these students receive partial exemption from strict attendance requirements for compulsory activities. The statutory framework acknowledges that representing thousands of students is fundamentally incompatible with rigid attendance policies designed for students without such responsibilities.

- The system includes protection against academic discrimination due to association commitments—a recognition that some academic staff might (consciously or unconsciously) penalise students whose primary focus isn’t exclusively their studies.

- There is, of course, accountability built into the system. To claim this special status, student leaders must be formally registered with the National Youth Association Registry (RNAJ)—ensuring that these protections apply to those with genuine representative responsibilities rather than casual involvement.

- What makes this system particularly effective is how it shifts the framing—student leadership isn’t treated as a distraction from “real” education but as a legitimate form of learning and civic engagement that deserves formal recognition and accommodation.

(Beyond association leaders, Portugal’s framework extends statutory protections to diverse student populations navigating complex life circumstances. Student-workers receive exemption from minimum attendance requirements and alternative assessment options—acknowledging that economic necessity shouldn’t derail educational progress. Student-parents benefit from justified absences for childcare emergencies and priority scheduling for classes that align with childcare availability, while pregnant and breastfeeding students receive comprehensive protections covering prenatal appointments through postpartum recovery. Student-athletes gain the right to miss classes for officially recognised competitions without academic penalty.)

School plays sell out

We bang on a lot about It’s the difference between what we might call the “school play” and “Broadway musical” approaches to SU activities – and Portuguese institutions have decisively embraced the former.

Take the Halloween event at Estádio Universitário de Lisboa. Rather than being centrally planned and executed with professional precision, it is compiled with each component organised by one of the faculty SUs – a patchwork that prioritises widespread involvement over polished delivery in a way that also means every faculty body is out helping to sell tickets.

The approach sacrifices some efficiency and consistency, but gains something far more valuable – a sense of ownership and emotional investment among participants that no amount of professional coordination can replicate. It’s theirs.

Where UK students’ unions might deliver services or events through professional staff teams working to standardised outcomes frameworks, Portuguese counterparts maintain a deliberately decentralized, student-led approach. One faculty SU we met generated a turnover of €270,905.48 from diverse revenue streams including recreational activities, merchandising, and services – all with just one member of staff. NOVA’s Biomedical Nucleus, runs multiple initiatives from weekly BE News updates to the “Biomed Explica” tutoring program without professional oversight.

These are operations that lack the slick professionalism of their British counterparts, but they compensate with extraordinary levels of student participation and responsiveness to local needs.

The approach is partly because of what it is expected universities, SUs and students will each respectively do. Even if we look at academic support services – an area increasingly professionalized in UK institutions – the “Biomed Explica” tutoring program doesn’t require elaborate quality assurance frameworks or standardized training, it just connects knowledgeable students with those seeking help.

Similarly, we saw mental health programmes (designed to address drop out) notable for how student associations bid for funding “to bolster or establish group social mentoring programmes” – creating peer support initiatives that will “transfer to the SU next year” rather than being permanently managed by professional services.

Portuguese institutions trust students to develop and deliver services, accepting that while the results may sometimes be uneven, the benefits of widespread participation outweigh the costs of occasional inconsistency.

What’s also instructive is how this decentralized approach accommodates adaptation to local contexts. The 36 student nuclei at NOVA FCT don’t need to align with a unified strategic plan – they’re free to develop activities that respond directly to the specific needs of their academic communities. When the Environmental Engineering nucleus creates “GreenWish” magazine or the Mathematics nucleus organizes subject-specific events, they’re not asking permission from a central authority or measuring success against institutional metrics – they’re simply identifying gaps and filling them.

And far from leading to chaos, the approach allows for remarkable coverage – at that Mathematics nucleus, 150 of the 850 students studying the subject are active volunteers.

This isn’t to say that Portuguese student organizations lack structure or accountability. Each faculty and university-wide association has clear governance mechanisms, from the Direção (executive board) to the Conselho Fiscal (fiscal council) that monitors financial compliance. But critically, these structures exist to both to facilitate student activity and to regulate it.

Scaffolding

It’s partly about community scaffolding – the basic organising principles of the student body. Where UK universities (and their students’ unions) tend to address student needs through specialized professional units – careers services, wellbeing teams, specific departments – Portuguese institutions route resources through discipline and programme-based associations, creating multidisciplinary hubs of student activity.

Events like AEFCT’s “Jornadas Tecnológicas” (JorTec) illustrate it – a multi-day academic and career festival for one faculty featuring “lectures, workshops, and activities coordinated by 14 student committees representing 15 degree programs, involving [volunteers from] around 200 students.”

Rather than a centralized careers service planning and executing, the responsibility and ownership belongs primarily to students themselves, with professional support remaining largely invisible in the background.

The approach fundamentally reshapes how students conceptualize participation. In the UK, the dominant narrative centers on individual representation – “be a rep” for your course, stand for election to council, volunteer as an independent officer. The Portuguese system foregrounds association and collective action at every level.

When a new student arrives at a Portuguese university, they aren’t immediately encouraged to take on a solitary representative role – instead, they’re invited to join their programme’s association, where they’ll find a community of peers working together on shared challenges. Here at Tecnico what we’d call an academic society is literally listed at the bottom of every course page.

The philosophy is embedded in institutional language – the term “associative” appears repeatedly throughout Portuguese SU and university documents, positioning collective activity as the foundation of student engagement rather than an optional extra.

The scale aligns well with what community cohesion theory tells us about effective democratic communities. Research suggests that democracy functions most effectively in units of approximately 1,000-5,000 people – precisely the size of many faculty-level student associations in Portugal. At this scale, representatives can maintain genuine connections with their constituents, and participation feels meaningful rather than tokenistic.

The nested structure – programme associations feeding into faculty unions, which in turn connect to university-wide bodies and city federations – creates multiple communities of appropriate scale rather than attempting to stretch a single democratic structure across tens of thousands of students.

This approach also transforms how students access support. Rather than directing students to centralized professional services, the default pathway in Portugal is often “go see your association” for issues ranging from academic concerns to career guidance or social support. The nucleus (academic societies) bodies don’t just run academic events – but also offer tutoring programmes and mentoring initiatives. And they all look student led, because they are.

Rituals, traditions and Roosters

One of the most remarkable things we noticed was an emphasis on ritual and tradition – cultural tent poles that create meaning, community, and identity in ways that most UK institutions have either lost or never fully developed.

The Queima das Fitas (“Burning of the Ribbons”) is probably the most iconic – a May celebration marking graduation where students ceremonially burn faculty-colored ribbons that have adorned their academic regalia. In Coimbra, this tradition evolved from the mid-19th century practice of burning ribbons tied to students’ notebooks, symbolizing liberation from academic burdens. Today, it encompasses parades, concerts, and traditional serenades – becoming a community-wide celebration that connects generations of students through shared experience.

Then there’s the Queima do Galo (“Burning of the Rooster”) tradition in Barcelos, where students burn a large rooster effigy in a public celebration marking the end of Lent and the arrival of spring. This tradition merges religious symbolism with local folklore, connecting to the famous legend of the Galo de Barcelos, where a rooster miraculously proved a man’s innocence. For students, participating in this ritual isn’t just about celebration but about embracing local cultural heritage and feeling part of something larger than their immediate academic experience.

Some deliberately scaffold the entire student journey – not just the endpoint. In some universities the Latada (“Tin Can Parade”) marks the beginning of the academic year, with freshers dragging tin cans through streets, culminating in a symbolic baptism (often in a local river) to mark official academic induction. It creates a powerful liminal experience, helping students process their transition into university life through embodied ritual rather than just bureaucratic enrollment. At ISTEC, the Freshers’ Parade described in the Freshman handbook also transforms the disorienting first days of university into a collective journey with shared meaning and purpose.

Even the superficial aspects of these traditions carry deeper significance. The practice of adding patches to the Traje Académico (the iconic black suit and cape ensemble) creates a visual record of a student’s experiences and achievements. Each patch – representing an academic milestone, participation in a student organization, or significant event – turns the uniform from generic academic attire into a deeply personal artifact that simultaneously signifies individual journeys and collective belonging. When students proudly display these patches, they’re not just decorating their attire – they’re proclaiming their place within the community’s history and traditions.

There are even traditions that specifically mark the transition to second year for UFGs – a point where students often struggle with motivation and belonging in the UK context. AEFCT’s Second Year Welcome events acknowledge this transition as worthy of celebration, recognizing students’ progression from novices to more established members of the academic community. And the Environmental Engineering nucleus at Coimbra honors this transition through its Gala Gota D’Ouro, a social event celebrating the student community and marking significant milestones in students’ journeys.

Student-led musical traditions play a particularly powerful role in Portugal. The Tunas – student musical groups like TAIPCA (the male Tuna Académica founded in 2001) and TFIPCA (the women’s Tuna formed in 2002) – preserve Portuguese heritage through performances that connect contemporary students to centuries of academic tradition. At IPCA, these groups have become “central to campus life,” not just performing music but leading charitable initiatives like IPCA Solidário, merging cultural expression with social responsibility.

Even academic and professional events take on this community-building character. JorTec at NOVA FCT features lectures, workshops, and activities coordinated by 14 student committees representing 15 degree programs, involving around 200 students. And MADweek at the Faculty of Architecture brings together students, alumni, professors, and professionals from the fields of fashion design, architecture, and design over ten days of programming that enriches both academic experience and professional development while reinforcing community bonds.

Traditions also create multi-generational connections. The AEFA Rewind exhibition celebrates the 46-year history of the association through a gathering that invites students, alumni and staff to reconnect, share memories, and honor AEFA’s legacy. The Noite do Antigo Estudante (Night of the Former Student) event held during Queima das Fitas brings alumni back to participate in current student celebrations, creating tangible continuity between past and present.

For UK SUs looking to rebuild or reinvent traditions, the Portuguese examples offer solid inspiration. Creating rituals that mark transitions throughout the student journey, not just at graduation, designing traditions with multiple levels of participation, from casual attendee to core organizer, and incorporating visible symbols (like patches on academic dress) that acknowledge achievement and belonging, all look like solid approaches. Building intergenerational connections that link current students with alumni also seems to matter.

What about representation?

While our observations on Portuguese student engagement have focused heavily on the social and cultural dimensions of campus life, it’s crucial to recognize how deeply academic matters are woven into the same associative structures. What was clear during our study tour was a fundamentally different approach to academic representation – one that doesn’t artificially separate academic advocacy from the broader student experience, but integrates them within the same community frameworks.

Larger courses (“programmes”) with greater flexibility and choice within them empower students to shape their educational pathways according to their interests and aspirations. At Técnico, for example, we observed how students can accrue credit in a multidisciplinary way, crossing traditional disciplinary boundaries to create personalized academic journeys. It not only enhances student satisfaction by increasing autonomy, but also helps universities respond more effectively to financial pressures by allowing more efficient resource allocation across departments.

Or take assessment. Rather than clinging to what might be called a “meritocracy of difficulty” – where academic rigor is equated with high-stakes assessment and limited opportunities for redemption – Portuguese institutions routinely provide every student with multiple attempts at assignments and examinations. This isn’t seen as diluting academic standards but as recognizing that learning happens at different paces and through different pathways. The result is a significant reduction in assessment-related anxiety and associated mental health challenges, without compromising the depth or quality of learning outcomes.

These didn’t happen by accident. Student associations across Portugal maintain comprehensive position papers known as “Moção Global” – essentially standing policy books that articulate the student body’s collective vision for higher education. The AEFCT Moção Global, for instance, offers a remarkably sophisticated critique of the law of HE – Regime Jurídico das Instituições de Ensino Superior (RJIES), identifying how reforms have “reduced democratic governance and student representation in decision-making bodies” and advocating for specific changes to “restore democratic balance and clarify institutional responsibilities.” Similar documents at AEISTEC and AAC present detailed demands across financing, access, curriculum structure, and social support mechanisms.

These aren’t just aspirational documents gathering dust on a shelf. They provide incoming student representatives with a clear mandate and agenda when entering institutional governance bodies – from faculty councils to university-wide committees. Because this educational policy work is embedded within the same associative structures that organize social and cultural life, it benefits from much broader student engagement than we typically see in UK institutions.

The result is a fundamental shift in campus conversations about academic policy. When the Comissão de Responsabilidade Social (Social Responsibility Committee) at AEFCT organizes initiatives on topics like racism, mental health, and social aid, these aren’t seen as extracurricular concerns distinct from academic matters but as integral aspects of the educational environment.

Similarly, when student associations bid for funding “to bolster or establish group social mentoring programmes,” they’re addressing academic support needs through community-based approaches rather than through individualized service provision.

The integration of academic advocacy within broader associative structures also creates powerful continuity. New university-wide leaders typically emerge from faculty and programme-level associations, meaning they’ve already worked alongside other student leaders and understand both the mechanics and culture of representation. Instead of starting from scratch each year – as often happens in UK students’ unions – incoming officers inherit not only policy positions but relationships and strategic vision from their predecessors.

Perhaps most importantly, this approach to academic representation recognizes that students are more than just consumers of educational services – they are co-creators of the academic community. The detailed AEIST proposals for educational reform emphasize “placing students at the center of an inclusive and democratic education system” and advocate for “greater autonomy and accountability in higher education institutions.” This language reflects a fundamentally different conception of the student role – not as customer seeking satisfaction, but as citizens seeking participation in shaping their educational environment.

There’s so much more that we could say – not least about the acres of space we saw dedicated to students just hanging out or running their activities. But mainly a huge thank you to the crew at FAIRe, a national body that represents Portuguese local students’ unions and works to promote the internationalisation of both the student movement and higher education in Portugal.

Founded in 2001, it operates as an umbrella organisation focused on strengthening its members through capacity-building, technical support, and training, and engages politically at both national and international levels, participating in networks like the European Students’ Union and MedNet, while advocating for students’ interests across Mediterranean, European, and Lusophone contexts.

And it’s all completely student run.