Rachel Reeves’ Spring Statement had little in it for the sector to celebrate.

The Office for Budget Responsibility,(who provide independent analysis of the country’s finances), downgraded 2025 growth forecasts from two per cent to one per cent.

For all the flurry of pro-growth activity since the election, the growth outlook to 2029 is basically unchanged. Economic growth and the much desired fiscal headroom (which gives the Government capacity for extra spending) still seem unlikely to materialise.

For universities who are hoping for a crumb of additional funding at some point in the future, there was nothing to settle their nerves about the increasingly difficult financial position the Government finds itself in.

Winners and losers

It’s safe to say that some sectors are doing better than others. Defence is clearly one of the winners. Starmer’s commitment to increase defense spending (made before the Spring Statement) to 2.5 per cent of GDP from April 2027 was a significant one. The measures taken to generate the fiscal headroom to pay for it- particularly cutting overseas development aid, and slashing welfare budgets – were not particularly popular ones. This is not an era of win-win policy choices – but boosting defence spending is a critical part of what Starmer’s government sees as a core responsibility: to position Britain as a steady hand in an unstable world.

The continuation of the war in Ukraine, renewed conflict in the middle east, and a second Trump presidency, renewed trade wars and global volatility all point towards this being the difficult but correct choice to make.

A significant uplift to its budget is the sort of things the higher education sector can only dream of. The increase to defence spending is not only massive, it’s also moderately popular. In a new Public First/Stonehaven poll, which looked at the trade offs the Government will need to make in the current era of hard choices, we found it which has moderate public support: 57 per cent back the uplift.

There is an opportunity for the higher education sector here that they may be reluctant to take. Universities are a relatively silent partner in the UK’s defense capabilities, despite the fact this is a clear area of opportunity. Defense companies are increasingly avoiding campuses for graduate recruitment after a rising wave of student protests – the Times reported that 20 companies have been advised against attending on campus events because of security fears.

Who will defend the defenders?

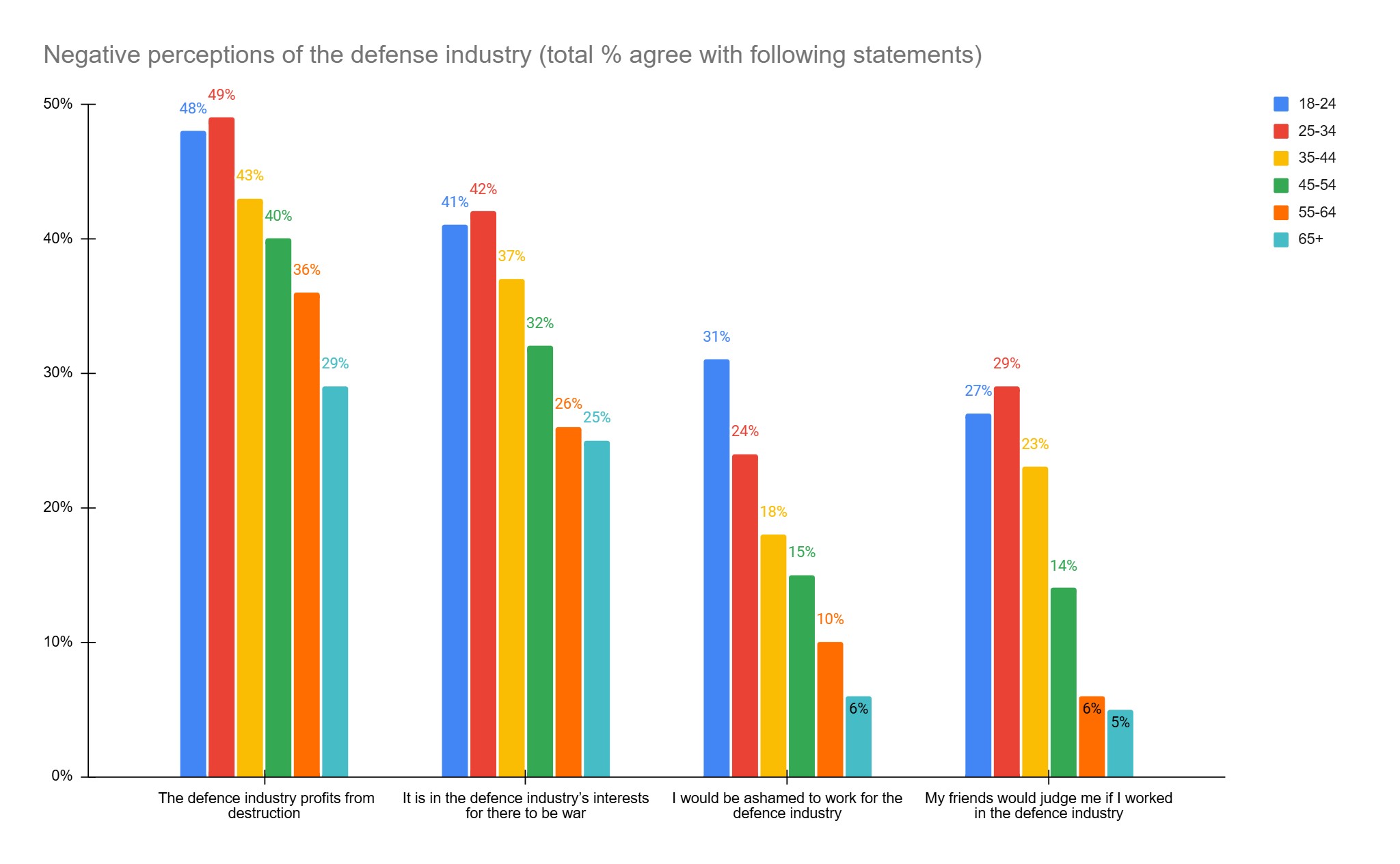

Many universities are trying to balance their industrial R&D and skills partnerships with the defense sector with a growing generational divide in attitudes towards the defense industry. Negative perceptions of the defense sector are particularly entrenched among Gen Z. Just under a fifth (17 per cent) of the general population say that they would be ashamed to work for the defense industry – but this rises to 31 per cent of 18-24 year olds. Nearly a third of 18-34 year olds say their friends would judge them if they worked in the defense industry. Going too hard on defence and being seen to be doing too much may risk a knock-on impact on student recruitment.

The increased investment in defense and security isn’t just about more soldiers and sailors and more ships and planes. It includes commitments on research and skills, and a ringfenced post of 10 per cent of the uplift for “novel technologies”. Increasingly, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) will become a major strategic procurer and funder in advanced research and development across the UK, which presents an increasingly rare and hard won opportunity for UK universities – and one where the public opinion is more balanced.

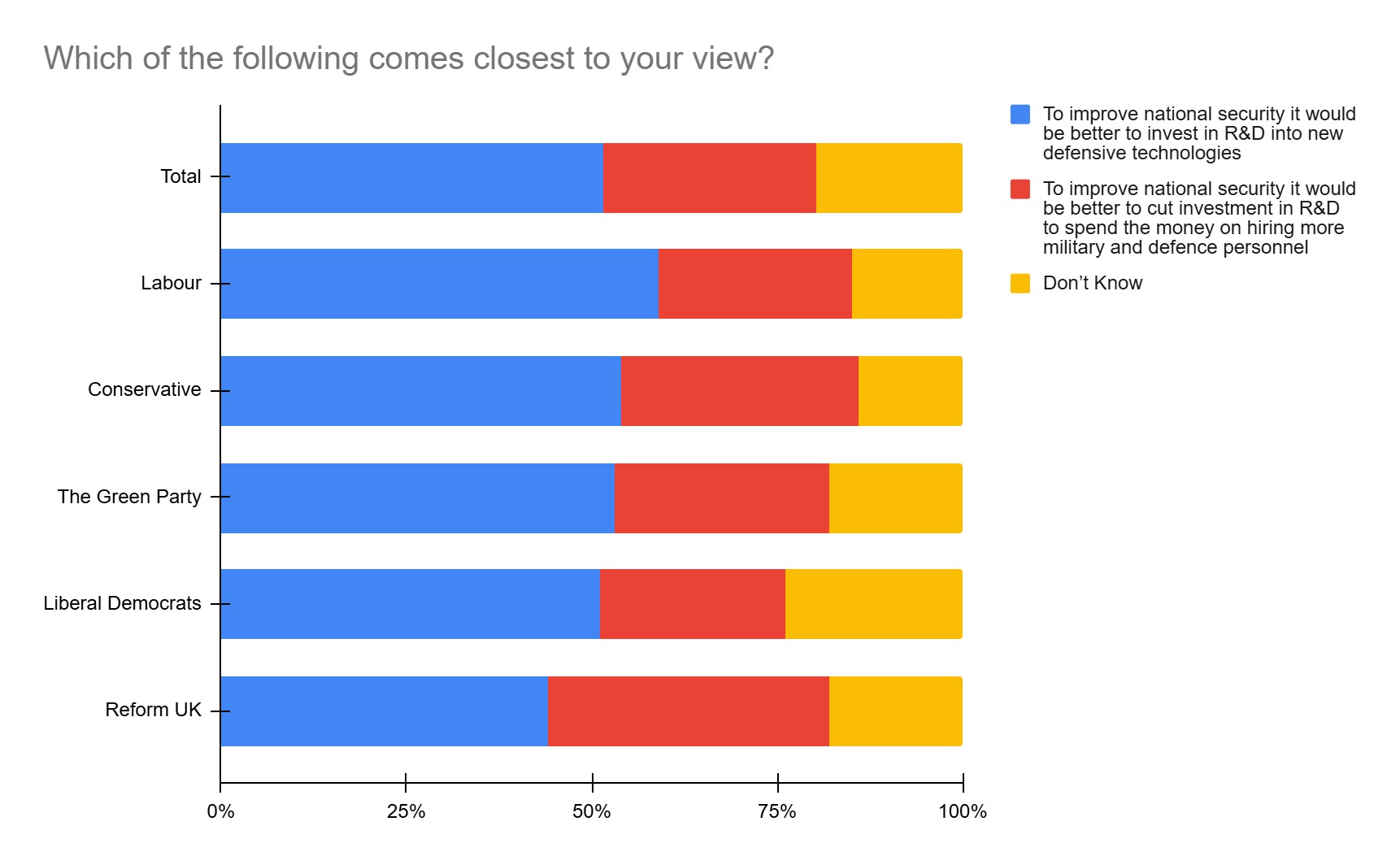

Talking about the role for university led R&D which boosts national security is a reputation win for the sector as a whole. In our large-scale research with the Campaign for Science and Engineering, which explored what the UK public think and feel about R&D, we found a strong preference for investment in new defensive technologies over more military personnel – a view broadly shared across all ages, and across the political spectrum

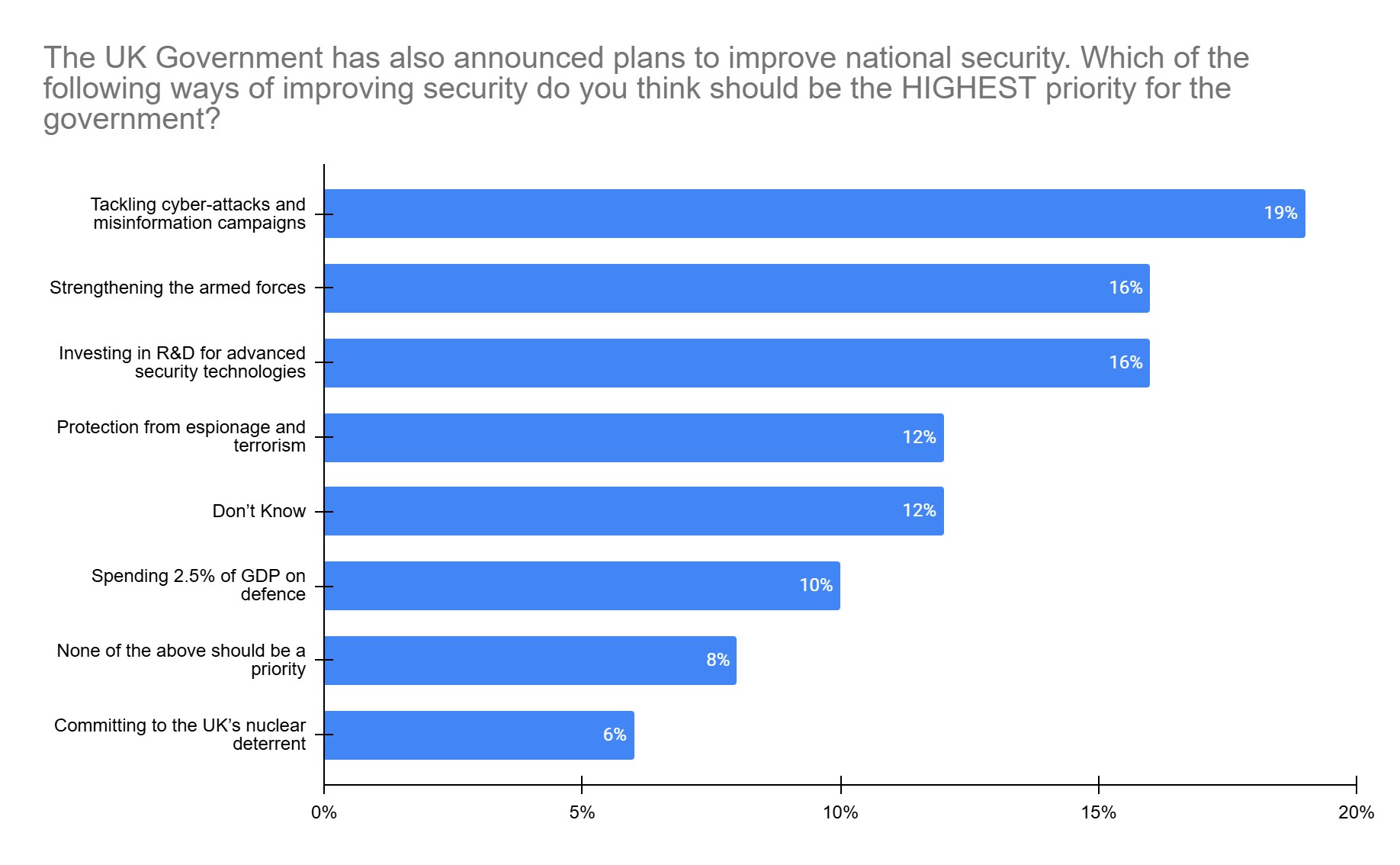

When we asked what the highest priority should be to improve national security, investment in R&D was the joint second most popular option, behind tackling cyber attacks and misinformation.

Hard choices

The defense sector as a whole might be an unpopular thing to talk about on campus. But there is a significant government investment being made in defense spending, and a clear moral and social argument that we live in a time when increasing the capacity and capability of our national security systems is the right thing to do. We know there is broad public support for this investment going towards research and development, and that there are significant skills gaps across our defense sector, impacting our broader defense and security offering.

In a time when politicians are making hard choices, university leaders need to be doing the same.

The modern armed services need highly skilled graduates in a range of roles – not just as professional soldiers, sailors or pilots but also in a myriad of supporting roles such as cyber security, communications, quantum technology, logistics, engineering, advanced manufacturing, foreign languages, and diplomacy. And equally too, the government will need academics and university research labs to step up, in partnership with businesses, to help design and roll out technologies that will support this expanded defence effort. This is both an economic case and a moral case – and one that universities should seize.

And if this is an opportunity which universities shy away from, they may be waiting a long time for the next economic windfall to come their way.

When the UK government is providing weapons and proactively giving military support to the genocide of Palestinians (presumably part of the “difficult but correct choice” Jess is referring to here), it is shameful to suggest that universities should support research and development of the government’s “defence” capabilities for their institutional financial gain. Grieving Palestinians would surely have something to say about the “moral case” for the death of their loved ones, and they will have no sympathy for the “hard choices” made by some university leaders.

This article is worryingly uncritical and strikes a bizarrely jingoistic tone. We should be deeply concerned about the growing influence of the defence and arms industries — sectors with devastating consequences for both human and planetary life — on the research and educational priorities of our institutions. It’s a profoundly depressing vision of education: universities reduced to little more than uncritical extensions of the military-industrial complex. Depressing to say the least.

The idea that research into defense could adversely impact on student recruitment is laughable.

At a time of war in Europe and the emergence of the USA as an unreliable partner it’s understandable that Governments are reversing the peace dividend they have enjoyed.

More interesting is the relationship between research into defence and those providers that will benefit from increased defense budgets, and policies that exclude arms and defence.

Universities have a genius for hypocrisy.

I don’t think it will make a big impact but it’s undoubtedly a tricky line to walk for universities when there is vocal student opposition to the arms industry. Last year many campus careers fairs were disrupted by protests against employers with (sometimes spurious) links to ongoing conflicts.

Who are Public First? “Public First is a Westminster-based research and PR firm founded in 2016 by political strategists and former Conservative advisers, Rachel Wolf and James Frayne. Wolf and Frayne have both worked with Cabinet Office Minister, Michael Gove, and government Chief Adviser, Dominic Cummings while Wolf is a previous adviser to Boris Johnson. During the COVID-19 crisis, the firm received over £1 million in contracts from the government without going through a legally required tender process. While this was justified as part of the government’s emergency COVID-19 response, it later emerged that parts of the work related to… Read more »

Actually, I don’t think universities SHOULD be supporting our government’s warmongering :/