How much are we paying to (for) students?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

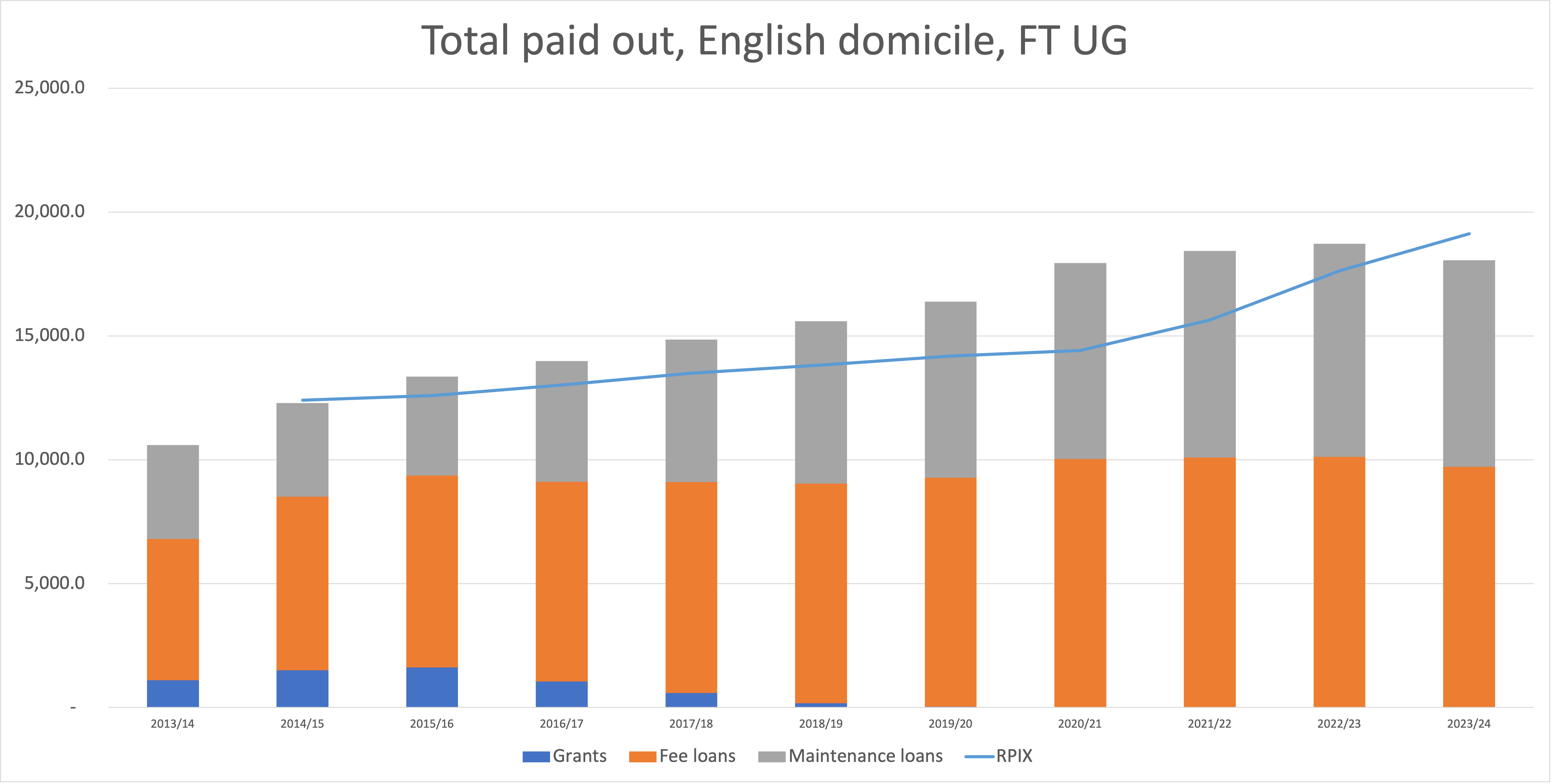

Here, for example, is the total amount paid out by the SLC to students and universities in support (FT UG, English domiciled):

You might look at that and say well, of course it grew by more than inflation – the number of students has been growing. If anything, the miracle there is that with far more students, the total loaned out is back on RPIX track – “efficiency” has been found both in students (forced to rely on jobs + parents + poverty) and universities (forced to rely on international PGTs).

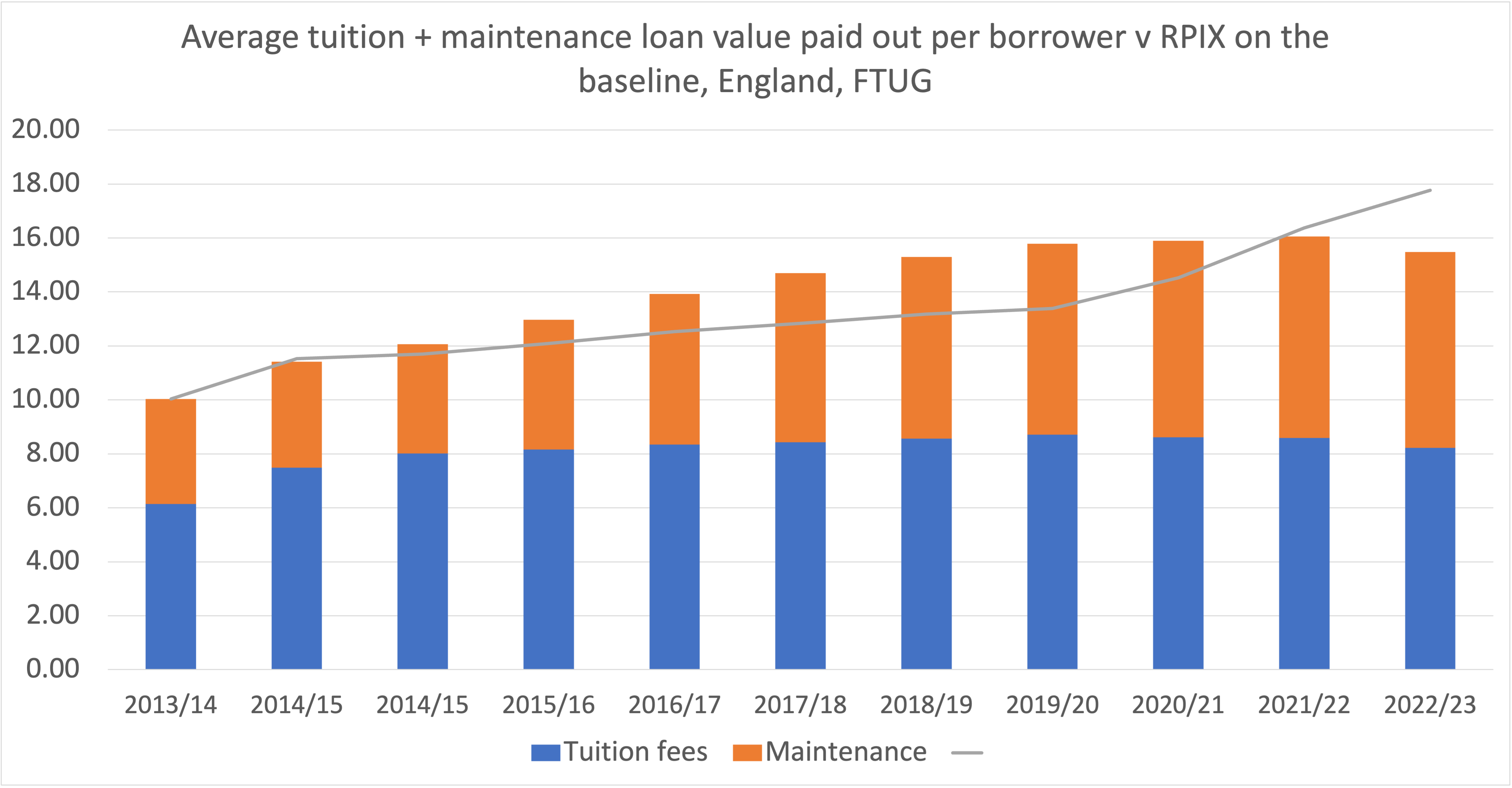

So let’s look at the average amounts borrowed per student:

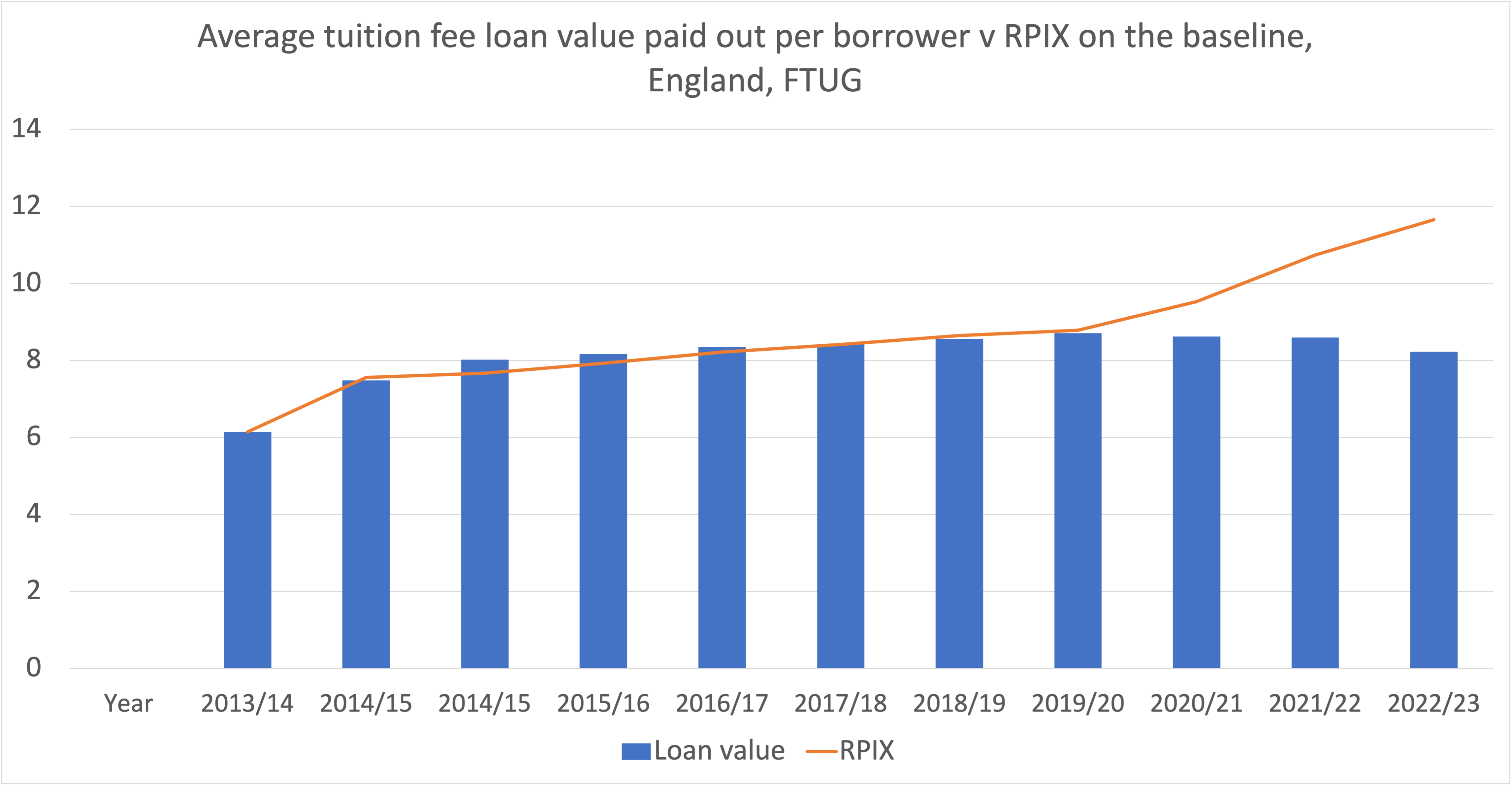

You might look at that and wonder what’s going on to have had the amounts grow faster than inflation when we know that fees have been frozen and maintenance entitlement hasn’t been going up by inflation. Here’s fee loans per student:

In the middle of the decade, you’re seeing overhang from previous years, as the long tail of courses of courses and providers not charging £9,250 all put their price up (some by becoming franchise partners, which in many ways is a way of evading the lower fee cap).

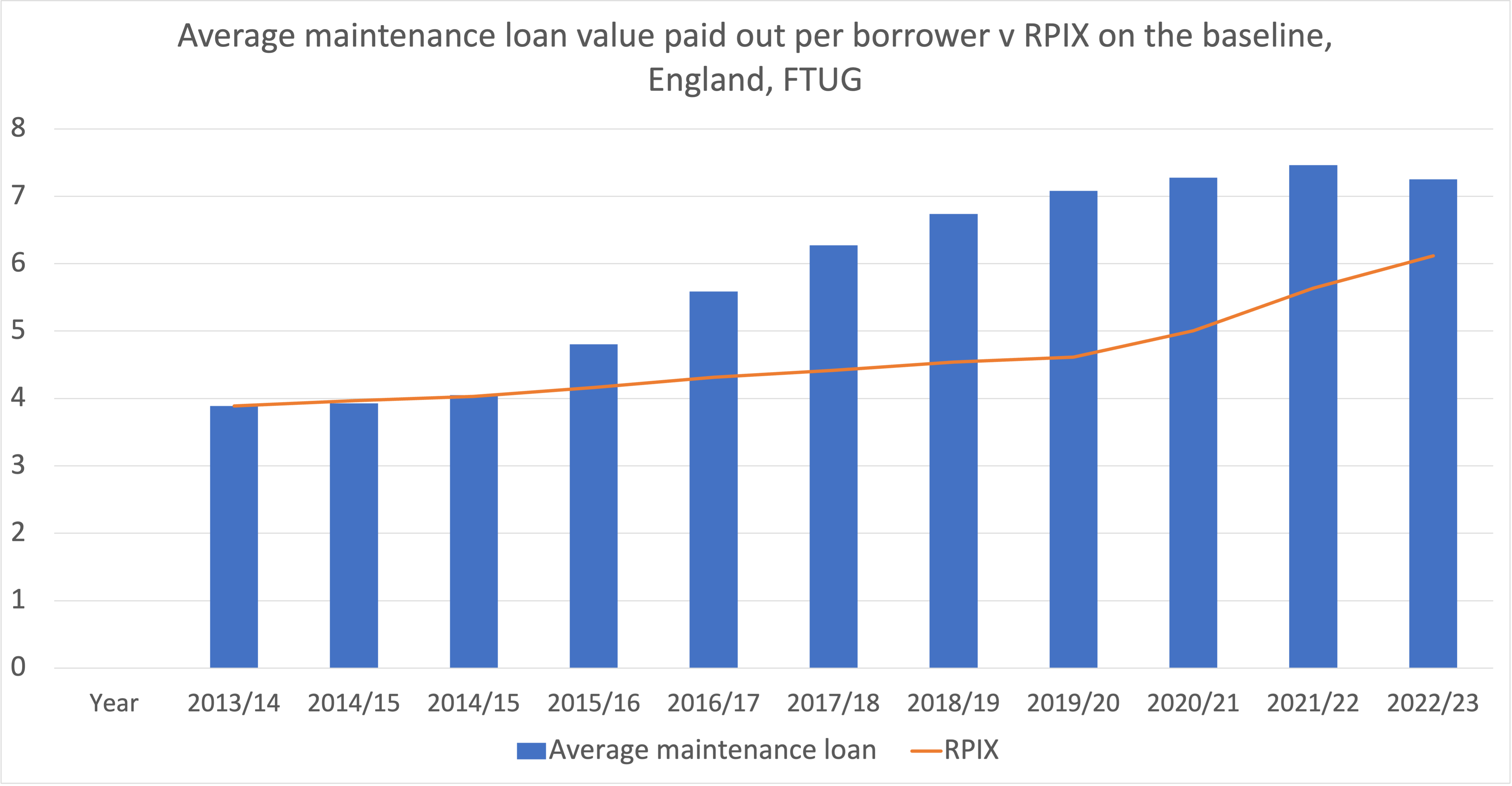

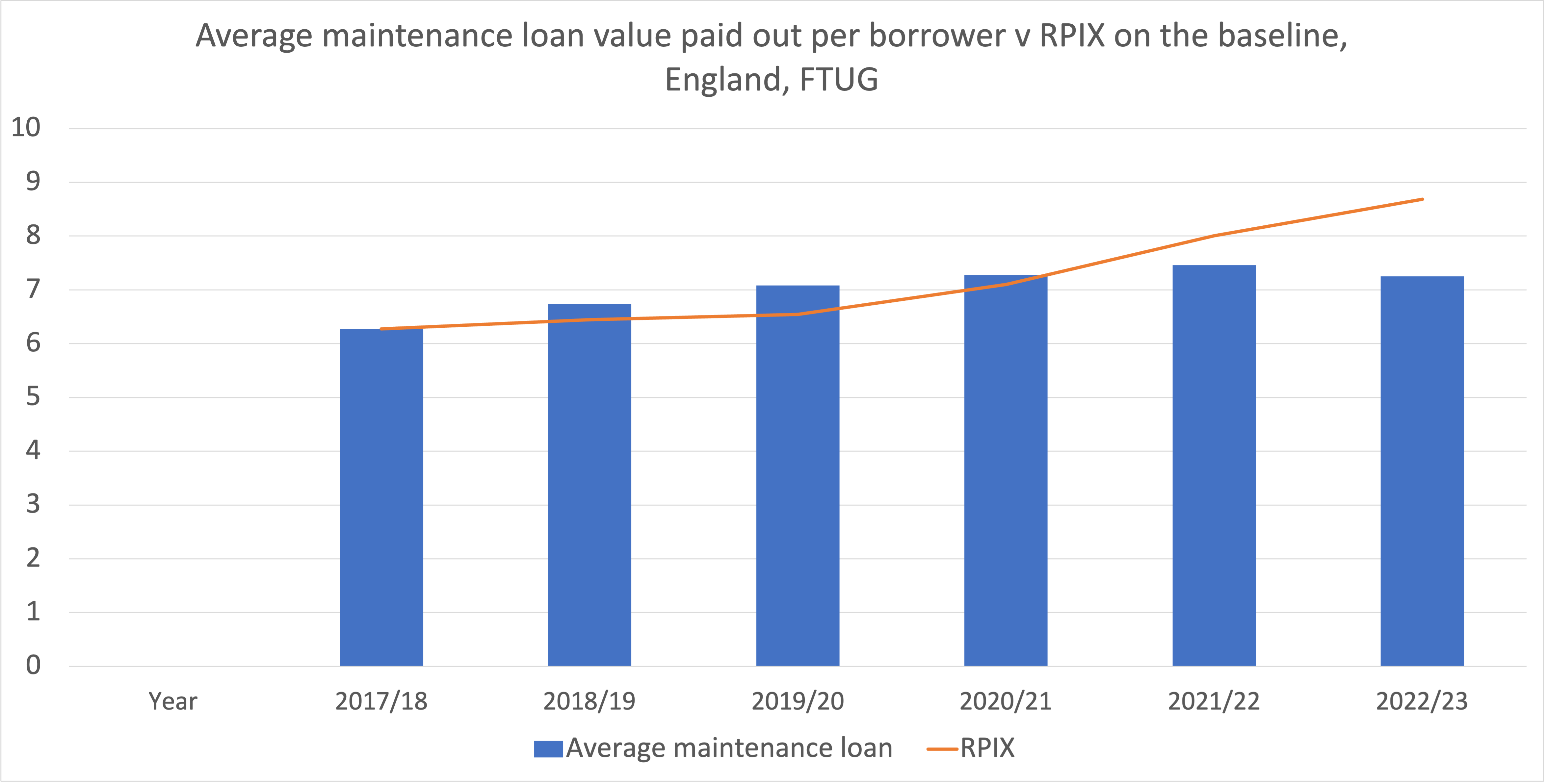

Here’s maintenance loans per student:

This time on the left you’re seeing the impact of the switch to loan rather than grant funding for students – then on the right you’re seeing the big inflation spike.

If we then just look at the second half, taking 2017/18 as a better baseline, that chart looks like this:

This time on the left you’re seeing what’s left of the instant (for students) switch to higher value loan rather than loan+grant funding, and the costs of admitting more (relatively) low income students. On the right, you’re again seeing the failure to uprate the totals for inflation and the fiscal drag of the parental contribution threshold stuck at £25k.

The total given out matters – a bit less than when some of it was grant, but more than it did when George Osborne took the cap on places off and replaced grants with slightly higher loans. That’s because Osborne’s books pretended that students would all pay back in full – now we calculate that they won’t, and the cost of borrowing the money to loan out to students has risen.

These, though, are the sorts of numbers that the Treasury will be looking at as the behind the scenes work on the spending review continues.