Beware the great unbundling implied in the LLE

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

2019’s Post-18 review of education and funding report made the case for continued fee freezes to “give HEIs time to rise to the challenge of greater efficiency and redesigned business models”, the vice chancellor on the panel was new Office for Students (OfS) chair Edward Peck, the foundation years funding cut was proposed in there, cutting interest on loans down to RPI was a feature (as was 40 year loan terms), and it laid the blueprint for the Lifelong Learning Entitlement (LLE) and its forthcoming funding of (most of) HE teaching by credit.

Augar didn’t predict a huge inflation crisis, of course – and the unfreezing of fees (with no DfE planning around contractual restrictions to putting them up despite wittering on (and off) about student contracts since 2017) will end up being three years late.

At the time, Augar’s panel argued that the sector could take a real terms reduction of 11 per cent between 2018/19 and 2022/23, as long as fees were indexed from then on – but beyond that, attempts to generate further savings would “jeopardise the quality of provision”.

Given that by the time the unfreezing happens this year in September there will have been a real terms cut of 35 per cent since 2018/19, we’d have to assume that the quality of provision is very much in jeopardy, or at least that the massive cut was covered by international students for a while – allowing some to ease off on doing the hard yards on efficiencies that are now very urgent for well-rehearsed reasons.

At the time of publication, Augar warned against a “pick and mix” approach to his proposals. They all say that, but there is a particular aspect of the ploughing ahead with per-credit funding that ought to give the government cause for concern.

Getting cross

The report noted significant cross-subsidies in the system – when you fund everything at a single “unit of resource” per student, that incentivises the supply of courses at less than the average cost to fund provision that costs more, with resultant problematic impacts on the “graduate premium” by subject:

We judge that the current method of university funding has resulted in an accidental over-investment in some subjects and an under-investment in others that is at odds with the government’s Industrial Strategy and with taxpayers’ interests.

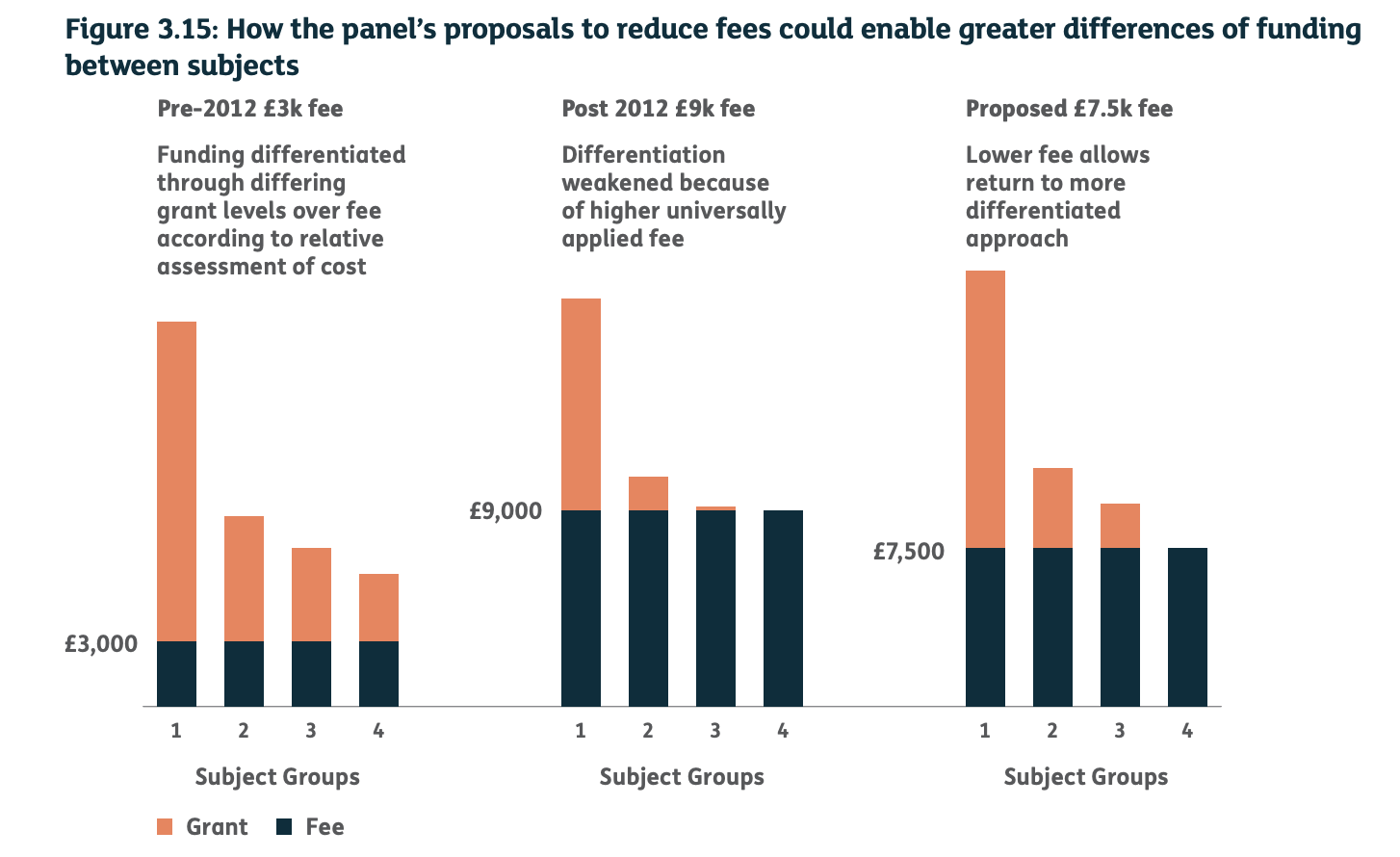

Augar’s solution was to cut the headline fee to a reasonable base cost of providing the lowest-cost courses – with the additional costs of providing higher-cost subjects (and to some extent higher cost students) was to be funded directly by grant.

At the time, most saw a headline fee cut of £7,500 as disturbingly close to Ed Milliband’s proposed cut to £6,000 in 2016 – an expensive bit of engineering that would have little political upside.

But the principle was important. From a student point of view, everyone gets into the same level of tuition debt – with Student A’s debt subsiding Student B’s more expensive characteristics or courses.

And it was that – and only that – in the panel’s proposals would have dampened down the tendency to supply courses that are cheap to teach regardless of the economic necessities, geographical impacts or real pattern of student demand.

The interest rate cut and the £7,500+ model, along with some money to go to further education to help balance the system, was to be paid for by extending the loan term to 40 years, as well as lowering the repayment threshold to median non-graduate earnings, which back then was £23,000.

But since then not only has inflation gone through the roof, the Treasury has pocketed the savings from 40 years and a lower repayment threshold instead of spending them on the higher cost students and subjects and FE.

And now that all results in major danger for the new government if it ploughs ahead with the basics of per credit funding as has been extensively worked up behind the scenes.

Cutting the cloth

Let’s imagine that the sector squeezes through its current woes and cuts its costs to the cloth on offer.

First, to the extent to which some subjects and some students cost more to deliver than the £9,535 a year we’re set to charge them, with skills minister Jacqui Smith busy dampening down expectations of an envelope increase, we’ll be expecting other students’ debt to fund them.

Not only do we have that ongoing “jeopardise the quality of provision” problem in general, we have the moral hazard of expecting individual student debt agreements to fund public goods – and as I’ve argued on the site previously, eventually doing that causes students to snap.

Second, ploughing on will exacerbate, or at least continue, the “offer up and expand what’s cheap to teach” trend that Augar said was at odds with the government’s Industrial Strategy and with taxpayers’ interests.

Who on earth is going to put on a pricey-to-deliver 30 ECTS credit STEM module for £4,768 a year in funding when the only way those books have been balanced previously has been to rob students on cheaper provision to pay for it?

Especially now that the Treasury has taken much of the “over-investment in some subjects” surplus for itself.

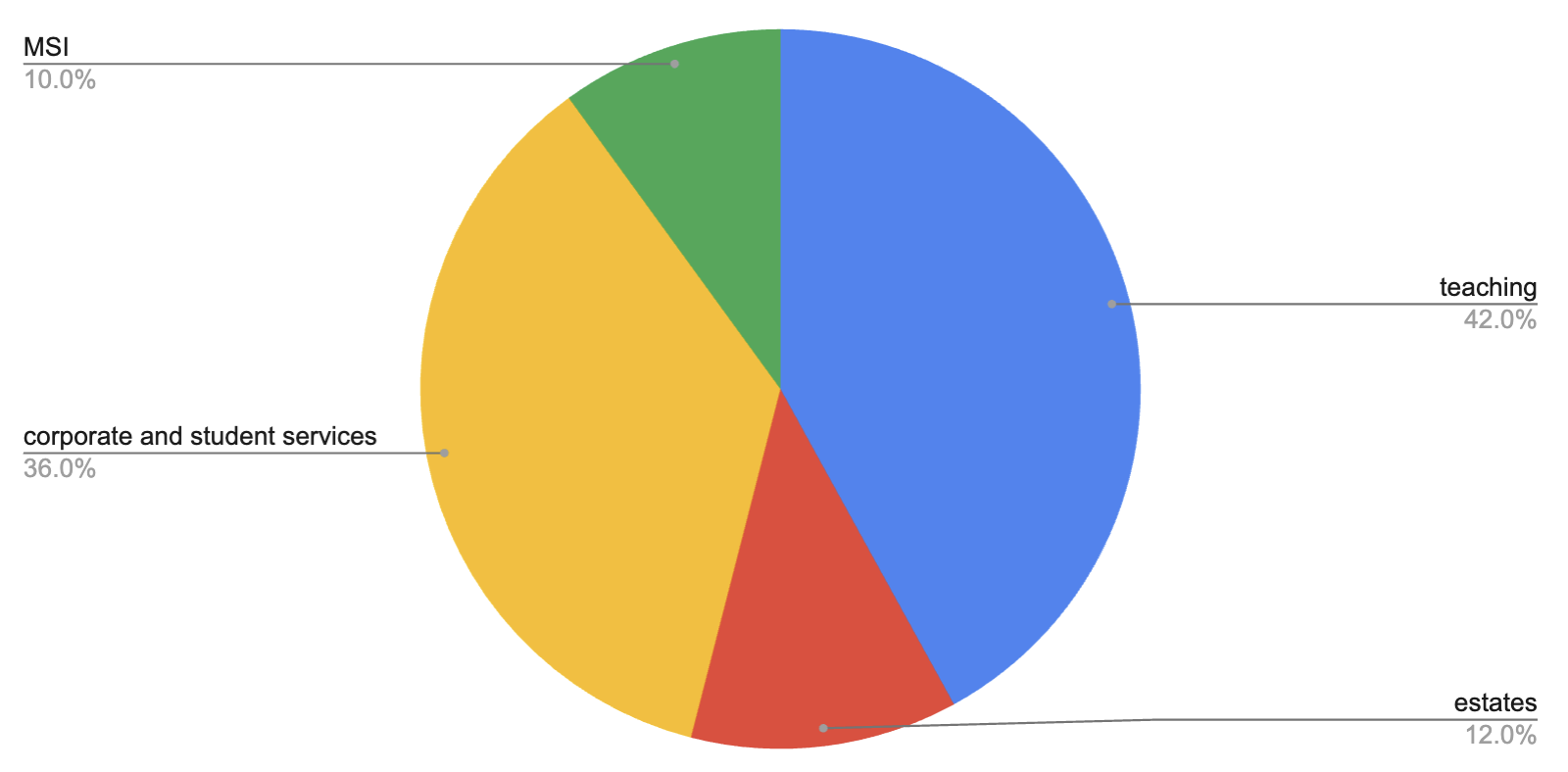

The third is the “rest of the money”. Augar drew on a supporting KPMG study that found that 42 per cent went on teaching, 12 per cent went on maintaining existing estates, 35 per cent on corporate services and student related central services and 10 per cent on the “margin for sustainability and investment” or MSI.

Despite nods to student services, civic duties and access and participation, Augar’s basic view was peppered with observations like “UK universities spend proportionally less on teaching and more on non-teaching staff and non-staff costs than their counterparts overseas”, opening up questions that weren’t really tackled at the time – like what would it be OK to cut in that 58 per cent, and what if a whole bunch of cowboys come in and offer even more “over-investment in some subjects” without any of those bells and whistles.

(I’ll note here that Augar also devoted a whole section to marketing and acquisition costs resulting from hyper-competition – a glance at any of the big for-profit franchisers reveals both big profits for themselves, and astonishingly high costs in that category).

But the fourth is the problem with per-credit funding generally.

How much for the garlic bread

Once the LLE transcript starts resembling an itemised bill in a restaurant, we’ll be explicitly saying to all students that that 20 credit module they’re on cost £3,178.

If the marking’s late, or the resources weren’t there in the library, or there was nowhere to sit in that lecture, or the lecturer was ill, on strike or drafted in during teach-out, why wouldn’t a student start grumbling about value for money at that level?

Maybe they should – but even if there aren’t delivery problems, the truth is that a collection of modules on a course itself involves cross-subsidy.

By definition, core modules are cheaper to teach (ie involve less attention) than specialist electives, and summative project and dissertation modules are supposed to involve a student trading off teaching for doing things for themselves so that they get more direct input in other modules – but that 40 credit dissertation module (where the supervision was shaky and in the end it wasn’t even marked) shows up on the bill as £6,356.

Why, a student may ask, should I pay £6,356 to engage in (40 x 20 = ) 800 hours of increasingly independent study – especially if the underpinning student finance system actually prevents them doing so, and if other students (on the same course, at the same provider or at another provider) got demonstrably better supervision or access access to resources for the same price?

Ditto for a student struggling, or retaking. When those things happen there’s often a fine line between failures on the student side of the equation and failures on the university side. The more we chunk down the credit, the less accepting students will be of the “academic judgement” magic wand that is waved to make provider failure disappear.

Few students right now demand “repeat performance” when things go wrong – but why should a student pay £3,178 to retake that 20 credit module that they thought was rubbish? And if the maintenance system continues to require them to enrol onto and attempt to complete 60 credits a year to get a “full” living costs loan when their personal circumstances, finances, disability or need for a little less intensity suggests less than 60, let’s not be surprised when they become even more disappointed than they are now.

The truth is that universities are bundles of services and courses, and courses are bundles of modules and services. The closer you get to putting a price on credit, the closer you get to undermining the need to spend more on some things and some people than others. Yet that is apparently what England is about to do – without the cushion of topping up that Augar envisaged.

A way forward

There is a way out of this. First, a team of people should be asked to re-do all of the sums in the Post-18 review of education and funding. Maybe “picking” the LLE is OK – maybe it’s fatally undermined because not everything’s been implemented and the Treasury’s nicked all the subsidy. We need to know.

Second, we also need to know where we are on that “quality of provision is very much in jeopardy” problem. The sector is never going to fess up the problem any more than it did when it was pretending that everything was fine during Covid – some proper external analysis involving students who’ve been around for a few years is sorely needed.

Third, if the government wants a raft of public goods from HE, it has four options:

- require then from every provider (including the office block for-profits);

- fund them itself;

- topslice the tuition fee and direct that budget better (better, at least, than endless exhortations, conferences, pamphlets and countervailing urges against regulatory burden);

- accept that they’re going to be eroded.

Ultimately, the present system just not fair on students without at the very least making explicit where their money goes. You sort of have to when you extreme-unbundle in this way.

Fourth, we need an update on that set of TRAC percentages, at least by provider and ideally by subject area. Why on earth should we expect applicants to not have access to that sort of data when making choices?

But fifth and finally, the government should pause for a moment. If the LLE goes ahead, England will not only have the highest tuition fees in Europe, but will also have the first system of barely-subsidised ECTS credit vouchers in the whole of Europe. Maybe there are reasons why nobody else has done this.

Put another way, we’re about to attempt to go even further down the rabbit hole of paying universities for inputs and regulating them at the margins on outcomes. Even where tuition fees aren’t differentiated by subject, almost all successful systems pay partly on performance. Pro-tip for policy makers – it’s always the incentives (mainly £££) that matter more than the restrictions. Nobody gets appointed or goes to work to “avoid being done by the regulator”.

Great analysis here and I agree with much of it, the current system has sound fundamentals (free at the point of use combined with income contingent repayments) but has been pushed to its limits and is serving all stakeholders (students, providers and government) poorly. One issue rarely addressed is its consequential and detrimental impact on research – yet another one of the myriad of cross-subsidies the system is riddled with. The LLE is a policy makers solution that I doubt the market wants or needs and its dis-economies of scale will make it expensive to provide and to administer. The… Read more »

Couldn’t agree more with the final paragraph, particularly its first sentence. There’s not always enough appreciation of just how ‘distinctive’ England has become in its higher education model, as set out/enshrined/promoted in HERA (https://lefttomyowndevices.blog/2024/09/09/silver-age/ ) – the rabbit hole we’ve gone down.

Great article that has made me rethink my instinctive support for the move towards funding at the credit level. Perhaps some kind of ‘course fee plus sum of module fees’ model might help address some of the problems you have anticipated. I didn’t agree with “we need an update on that set of TRAC percentages, at least by provider and ideally by subject area. Why on earth should we expect applicants to not have access to that sort of data when making choices?” When buying a car, I wouldn’t expect to know how much its bumpers cost to manufacture, nor… Read more »