Among the university initiatives which aim to amplify traditionally marginalised voices, disabled researchers are now throwing their metaphorical hats into the ring.

I am a member of a disabled researchers’ network and in a recent meeting, the question we asked ourselves were central to the raison d’être of the group.

How do we position ourselves? How do we manage the strength that comes with having a diverse group, while ensuring that all voices are heard equally? And – perhaps most crucially – what are the positive outcomes towards which we can orientate our group and our activities, within the existing structures?

Perhaps thinking about this via the lens of the overused yet helpful notion of “leadership and management” could help to clarify the tensions and dichotomies facing disabled students and inform next steps.

Vital functions

Leadership and management have separate and “vital functions” within any organisation – management is focused on efficient and reliable operations day-to-day, while leadership drives an organisation into the future.

These two concepts, so often put together and both crucial for an organisation to flourish, in some ways work against each other – as Professor Tony Bush explains,

Managerial leadership is focused on managing existing activities successfully rather than visioning a better future.

“Management” inevitably involves some element of instinctive resistance to change which threatens to destabilise routines and known outcomes. In my experience and from the personal anecdotes of disabled colleagues, it is apparent that we have experienced inflexibility in processes and resistance to adjustments which would have facilitated our research activities.

Maybe at least some of this resistance comes from a fear that equilibrium would be disrupted; giving the benefit of the doubt seems helpful in avoiding the “us” and “them” stance which is an obstacle to positive collaboration and moving beyond the past to the desired future.

The reality is that this is difficult to navigate. When our voice is an unexpected interruption, when the thorny issue of inclusive practices is raised, relationships can be affected. How can we lead the research environment within HE towards being more truly inclusive without ruffling too many feathers?

Leadership demands the flexibility to move towards future aims, or in the words of Roselinde Torres, being:

…courageous enough to abandon a practice that has made you successful in the past.

While we might not want the HE sector to “abandon” all current practices, it is apparent that change is needed to ensure true equality of access and opportunity. A model of “success” which marginalises disabled researchers is not true success; our argument is difficult to refute, and I’m sure nobody would openly do so.

However, agreement in principle is not the same as action in practice.

Fine by me

Everyone readily agrees with the idea of an inclusive research environment; but not everyone is proactively engaged in making this a reality, particularly when it disrupts the status quo.

Perhaps the crucial difference in perspective between the manager and the leader is that of immediate deliverables versus long-term strategic outcomes; and perhaps this can be used to consider the collective in the wider context of the university.

As disabled researchers, we are our own “leaders”; a label we may not seek out or desire, but which nonetheless can be seen in our daily activities, thought processes and planning.

We have to think ahead, mitigating barriers which non-disabled researchers simply do not have to navigate; and this difference is nobody’s fault, but it is useful to be aware of it in this discussion. This art of looking ahead is identified by Torres as one of the necessary traits for effective leadership; she explains:

“Great leaders are not head-down. They see around corners, shaping their future, not just reacting to it.

My point isn’t to suggest that disabled researchers are somehow better leaders than their non- disabled colleagues; but we have developed certain characteristics out of sheer necessity. As disabled researchers, indeed disabled individuals, we have to “lead” from the outset to overcome the barriers which are our daily reality.

Encountering barriers

We may face the uncertainty which comes with managing a chronic, long-term condition which dictates whether we are well enough to work on a specific date, at a specific time, and over which we have no control. For me, my modus operandi is to work ahead of every deadline – often perceived as being over-competitive – because I know that I may suddenly be forced into a work hiatus which, without this buffer, would put me behind.

We may encounter access issues – workspaces, and transport to those workspaces, which do not meet our most basic needs. Physical barriers – often assumed to be the most readily addressed – still exist. We may need to call ahead to ensure that we can simply get into the room – let alone have a seat at the table. In 2024, it feels like we should be further along than this.

As disabled researchers, in work and in life, we are in strategy mode constantly; looking ahead around every corner; planning for the next barrier we need to demolish if we are to continue moving forward.

We are forced to strategize – even when we don’t want to. Therein, perhaps, lies the rub.

Because we are proactive in reducing our barriers, we have an expectation or at the very least a hope that our colleagues, managers and in the broadest sense our employers will adopt the same stance.

When this is reduced to box-ticking exercises rather than a meaningful, consultative approach, this damages morale. When we must ask for adjustments – sometimes more than once – resentment builds; and if adjustments are promised then not delivered, relationships can suffer irrevocable damage.

We lead because we have to

Yet we continue to “lead” on this out of necessity; our voices are loudest on these issues for the simple reason that it impacts us the most, especially when organisations don’t get it right. From the discussions we’ve had within our network, I know that this can be a lonely experience, with researchers feeling marginalised, unable to voice their concerns to a listening ear, and finding that speaking out can result in feeling left out.

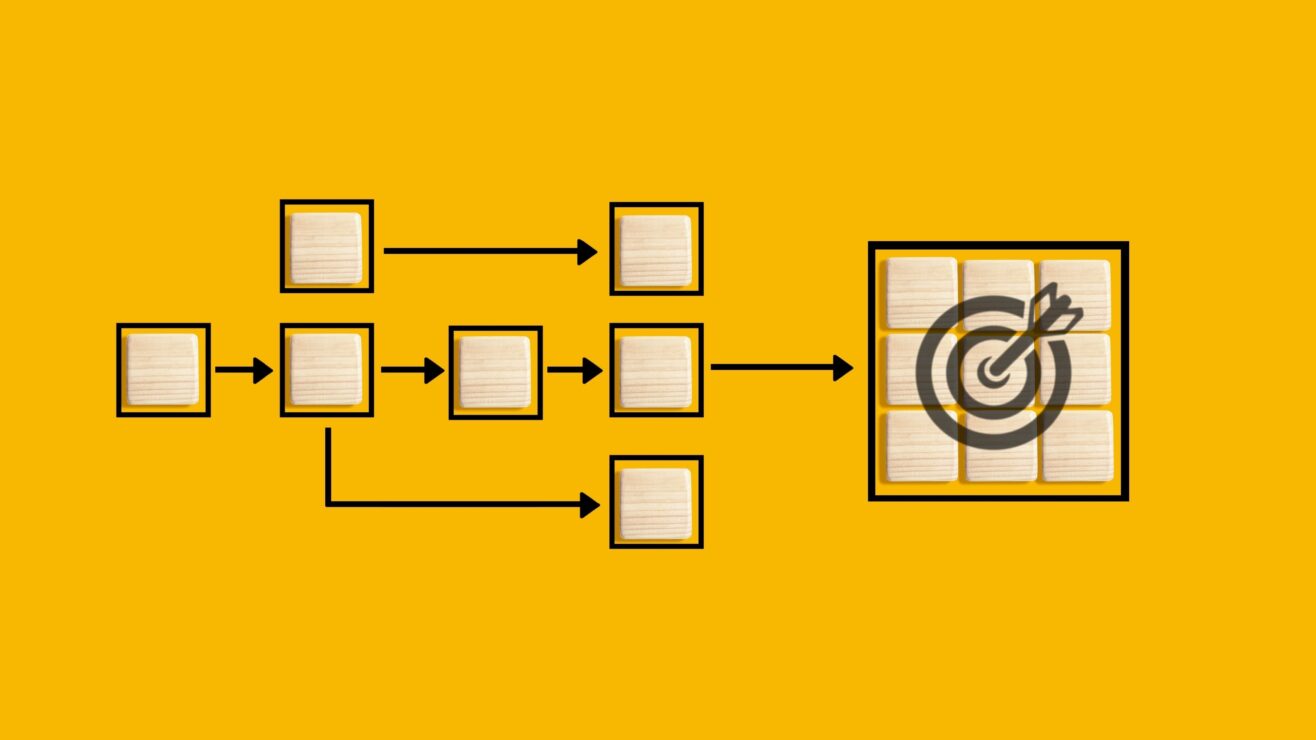

So how can we move collectively towards change? Perhaps we can take inspiration from the eight-step change model proposed by leading business consultant John Kotter. Here, a structured approach is described which will move a workforce collectively towards change.

Perhaps one of the most useful elements of Kotter’s framework is Step 2: “Build a guiding coalition”. What does this mean? It means that individuals of influence and power within an organisation need to be involved in change, or it may be rejected. This is a viable model: disabled researchers partnering with stakeholders across the sector to promote our vision of a fairer, more equitable research environment where lived experience is valued and the need for a continuous programme of improvement is recognised.

When all is said and done, this isn’t really a radical proposition. There are outcomes we want to achieve, and we need partners to achieve them. We need our voice to be heard at a strategic level. We need champions for inclusion to be nominated across the HE sectors, with a clear remit to work with disabled researchers to enact meaningful change. Activism isn’t incompatible with collaborative working any more than research is.

Both activism and research address a need, a gap in knowledge, a difficult dilemma, or an important issue, and ask the question: how can we do better, and why aren’t we doing better? This then leads to the next research question…and the next… and the next… and so ad infinitum.

There is no limit to how much we can learn or improve, and there should be no end to our willingness to keep learning and improving. This is surely integral to the whole ethos of higher education. We need to have open communication; create opportunities for conversations which might be challenging; and cultivate curiosity about how we can better understand one another and facilitate inclusive working environments.

Even in the most highly competitive business arenas, research has shown that a work culture which prioritises “psychological safety” – an environment where individuals feel secure enough to share their perspectives, both positive and negative – is the gold standard for employee productivity and happiness at work.

A recent study involving the work-life balance and happiness of women working in the financial sector concluded that:

…having diverse teams that can be honest allows for better outcomes.

At the heart of the change we are seeking is simply the opportunity to be honest in an environment which encourages this. So let’s blur the boundary between leadership and management; let’s have honest, if sometimes challenging, conversations; and let’s embark on this journey together.

A great article! thank you Zoe. Have you come across the research I and colleagues conducted (quite a few years ago now – but not very much has changed)? Here are a couple of articles reporting our findings:

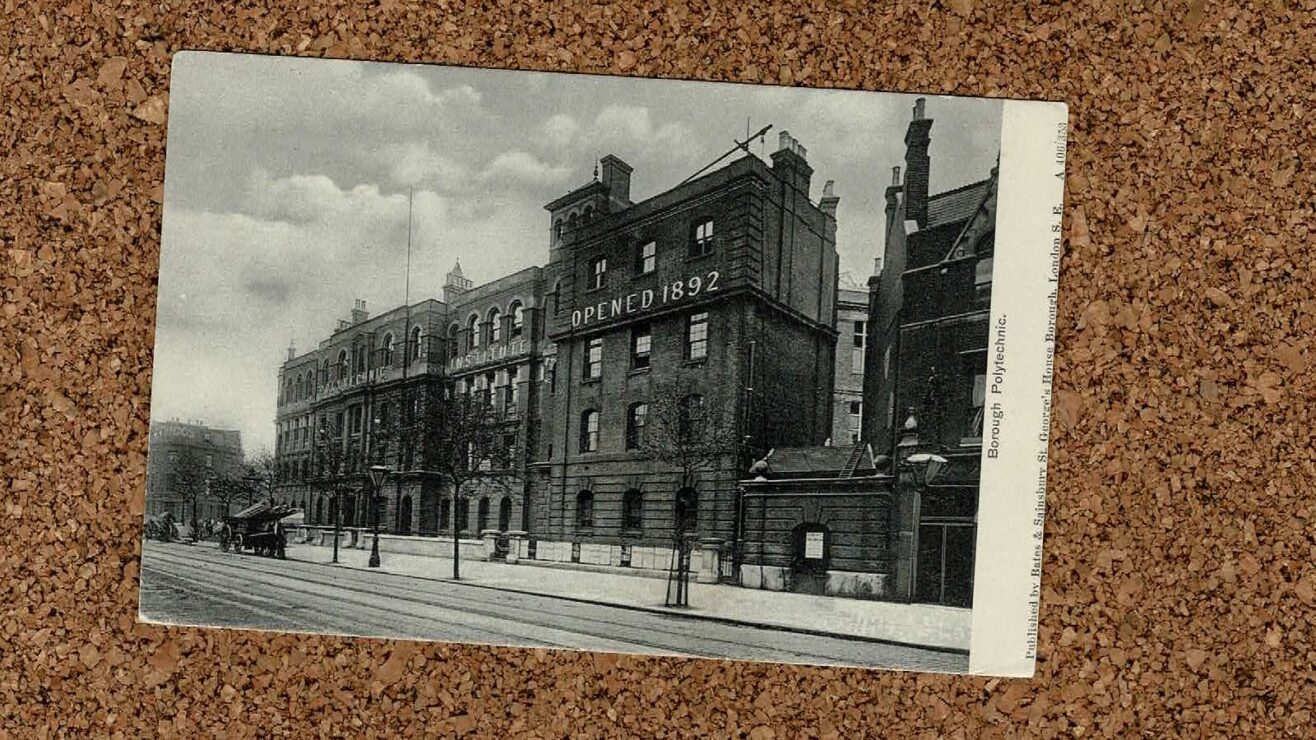

Brewster, S., Duncan, N., Emira, M., and Clifford, A. (2017) Personal sacrifice and corporate cultures: career progression for disabled staff in higher education. Disability & Society, 32 (7) pp. 1027-1042

Emira, M., Brewster, S., Duncan, N. and Clifford, A. (2016) What disability? I am a leader! Understanding leadership in HE from a disability perspective. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. 46(3):457-473

Thank you Stephanie – I’m glad you enjoyed it. I thoroughly enjoyed your articles. I hope that, if we keep writing about it, the tide will turn; if opportunities increase for disabled staff to move into leadership roles, maybe the shift in mindset that is needed for truly inclusive teaching, learning and research environments will start to occur.

PS – I did my PGCE at Wolverhampton University 2008-2009 and had a fantastic experience – so it’s very nice to hear from someone at the Walsall Campus! Zoe

This is a really valuable piece and perspective Zoe, thank you for sharing. I feel like the word ‘researcher’ can be swapped out with ‘manager’, to the same affect. Being a disabled manager in HE is to be disruptive, even when I’d rather a quiet life. I also find concepts of management and leadership are often considered to be one in the same, which limits the space for being innovative and reimagining the future (something most disabled people need to be and do on a near daily basis).

Thanks again for sharing.

Thank you Hannah – I’m so glad you left a comment, as it led me to your article “Higher education needs to get to grips with the language of neurodiversity”. This piece really resonated with me, especially this: “…the perspective the neurodiversity paradigm gives you to reframe a lifetime of experiences that never quite fit” – this 100% captures my life and in particular my on-going journey into, out of, and back into academia. Thank you to you, & to your co-author Neil Currant, for such an insightful, well-articulated piece. It has lifted my Monday morning.