Last year was quite a big year for the University of Silesia in Katowice.

Since his election (note not appointment) to the post, the university’s Rector Ryszard Koziołek had been thinking carefully about the future of the university.

Over the last two decades, the number of students at Silesia had decreased by more than half (from over 44,000 in 2003/04 to less than 20,000 in the academic year 2022/23). But they’d increased the number of fields of study from 34 to 83.

But this wasn’t just about chopping back some under-recruiting programmes. His wider worry was that the university, like other traditional institutions of knowledge (schools, libraries, museums) had ceased to be an irreplaceable center for creating and accumulating knowledge:

For centuries, this was possible thanks to the concentration of resources and experts, access to which was possible only within the university space and on the principles specified therein. The pandemic confirmed the university’s change of position, forcing us to function remotely. Although we passed this exam very well, the question about the future of traditional academic education has become even more pressing. The latest examples of students using widely available AI generators take the above problem to another level of complexity.

Koziołek’s presumption was that an abundance of knowledge sources and easy access to information had given rise to a new type of learner – the “over-informed” individual – who seems capable of learning anything independently, without a teacher’s guidance.

And the overwhelming flood of information had brought about new challenges – shallow understanding, misinformation, conspiracy theories, and a sense of confusion and exhaustion:

The model of education based on the simple transmission of knowledge from teacher to student will certainly be limited. On the other hand, practical skills will be necessary in the area of theorizing knowledge and falsifying theories, operating research methodologies, critiquing knowledge, critical analysis of discourses (with the discourse of algorithms at the forefront), the ability to verify sources of knowledge and the quality of information, as well as the ability to cooperate as experts from various disciplines. Therefore, many “learning outcomes” and, above all, the role of the academic teacher in the process of achieving them in joint work with the student.

Hence his definition of a student of the “near future” – a young person who has been accustomed to individualizing their choices since childhood:

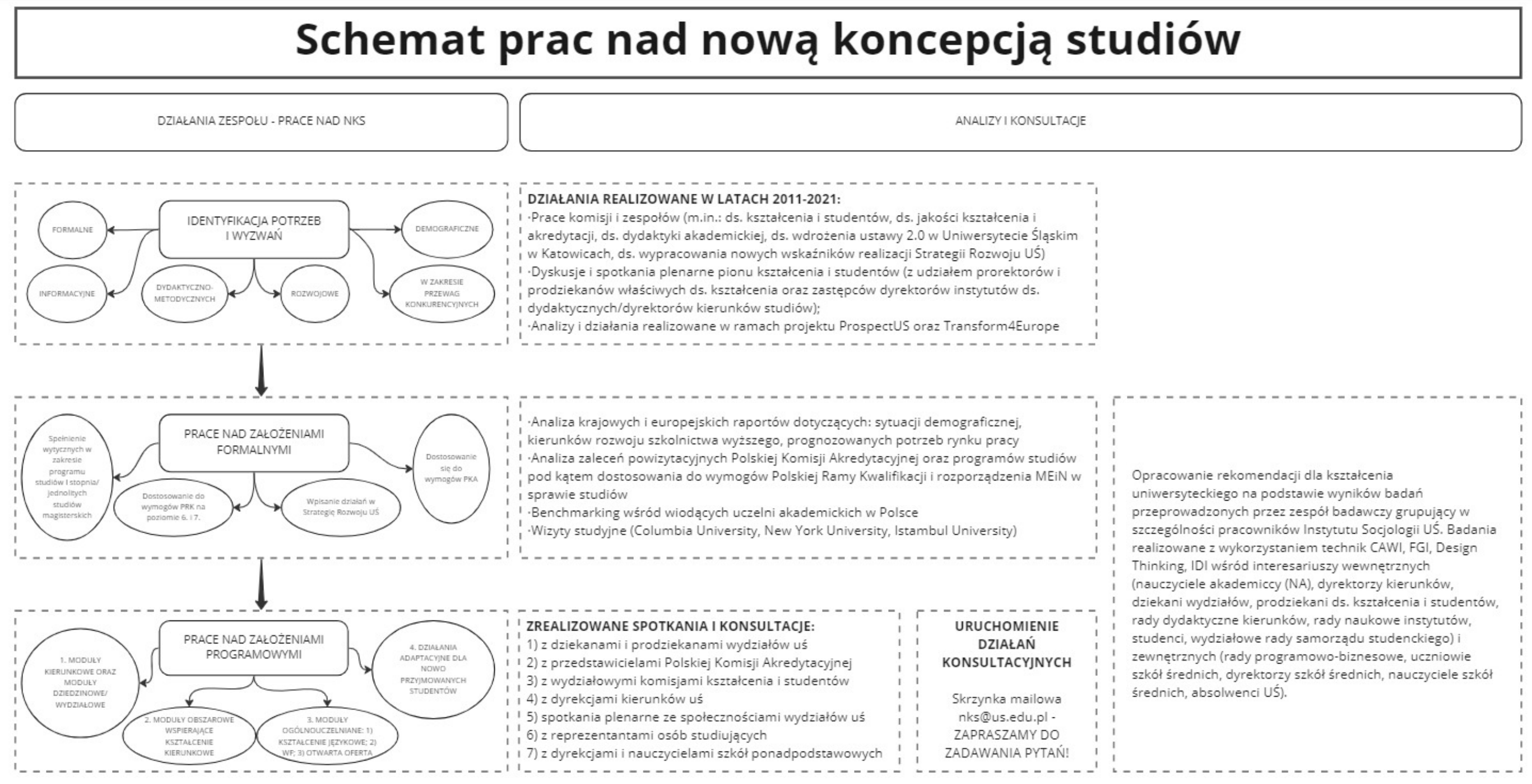

The New Study Concept assumes enabling students, to a substantially greater extent than before, to individualize their program of study by choosing from the offer of modules proposed at the university level.

So what might have looked like a curriculum rationalisation programme – of the sort plenty of UK universities are looking at now – was actually an opportunity to achieve two goals at the same time – offering students a useful and attractive form of study and enriching and strengthening specialized education.

The guiding principle is that graduates of a specialised university programme should leave with knowledge and skills that are both exceptional and distinct—something unattainable at more narrowly focused institutions like technical universities or medical schools.

So the new model for bachelor’s education includes two key components – specialised modules tied to the student’s primary field of study, and open university modules that enrich and connect this specialised learning with insights from other disciplines. This aim is to broaden students’ educational horizons, encouraging them to pursue individual interests and ambitions while preparing them for a diverse and interconnected world.

And naturally, eight student members of the project group were appointed by the SU to help shape the project and consult with students on its design and implementation.

Spin spin spin the place of justice

It’s one of the things we were reading about on the way to Katowice on Day Four of the Wonkhe SUs study tour to the Visegrad countries, where a group of student leaders and SU staff are on a five day tour of over 30 students’ unions, guilds, associations, and infrastructure organisations – learning about education, representation, student life and SUs from our friends in Central Europe.

Having parked the bus, we first went into the university’s new SpinPLACE – an impressive creativity and coworking center supporting innovation, entrepreneurship, and collaboration that’s based in a former bank in the city.

It houses initiatives like the Silesia Design School, a Start-ups Mill, a 3D Prototyping Centre, and R&D Fuse, and offers spaces for networking, design, and research. The activities create connections between students, academics, business, and local government, including career development, intellectual property support, and start-up mentoring – and it’s co-financed by the EU to boost regional innovation.

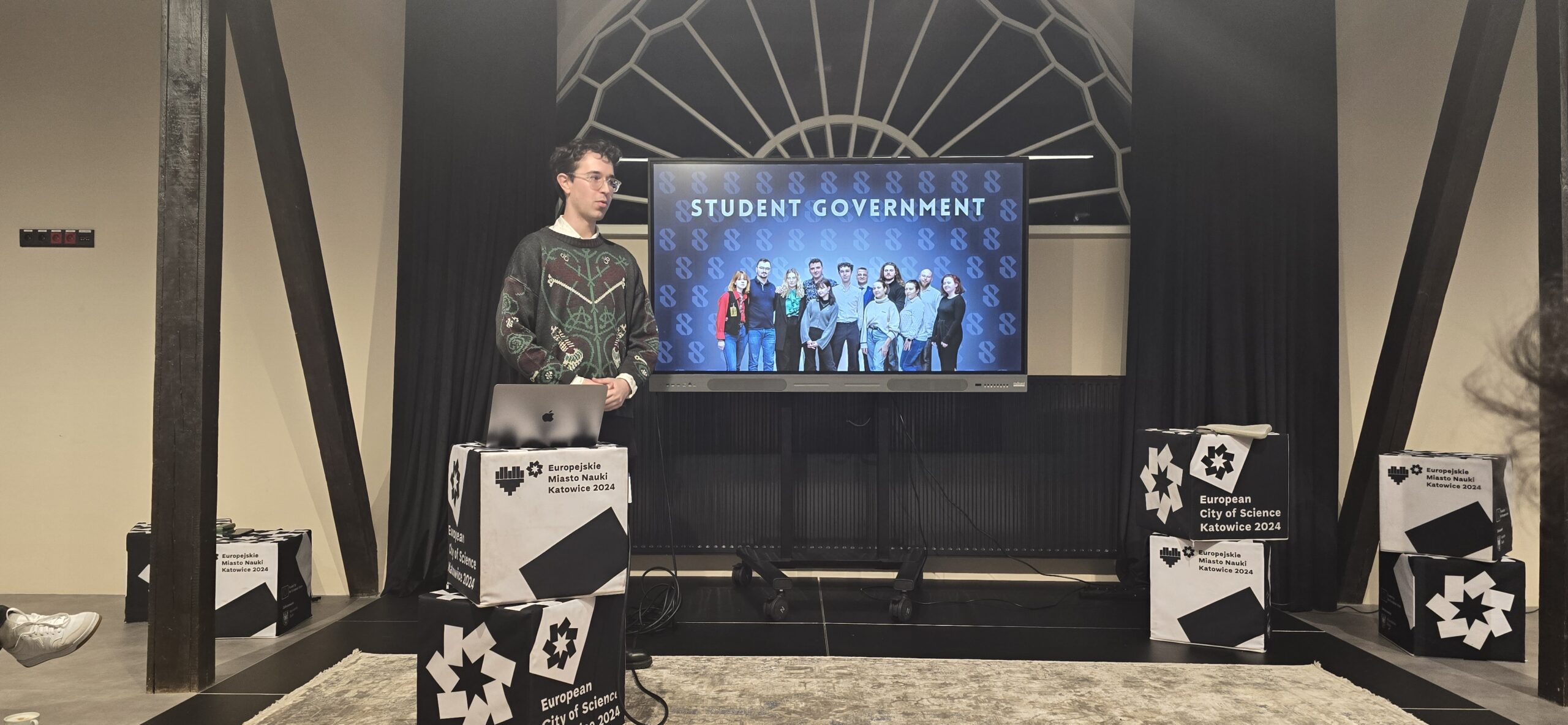

Impressive SU President Michael Szczesny kicked us off with a presentation that began by quoting the law – always a good sign – and given the content, you can see why.

Article 110 of Poland’s Law on Higher Education and Science establishes the existence, rights, and responsibilities of samorządy studenckie (student governments) inside universities – explicitly recognising students as a distinct group within the academic community with the right to self-representation and autonomy, and giving them the exclusive right to act as the voice of students.

In law they’re given the right to take part in decision-making processes, particularly in areas directly impacting students – like the allocation of student support funds, organisation of cultural or social activities, or the development of policies concerning education quality. They are also charged with organising student life – including cultural, sports, and volunteer activities – and have to be given adequate funding from the university’s budget to carry out their activities.

In each SU a mandating body has to exist – a formal assembly or council responsible for setting policy, making key decisions, and ensuring that the self-government represents the broader student community so it can lay claim to representative legitimacy – and is usually made up of student reps directly elected by students in faculties.

That then oversees (and appoints) the executive branch of the self-government, ensuring that student leaders act in accordance with the statutes and the broader interests of the student community.

These sorts of structures seem to be dying out in the UK in favour of forums, consultations and an ever bigger focus on the cross-campus ballot of the main sabbatical election – but there seem to be real benefits to having a stable and consistent “assembly” style structure in each SU in Poland, an issue we’ll return to on the site soon.

Dancing is my remedy

There’s some great events here – the Silesian Science Festival is one of the largest cultural and scientific events in Silesia, during which each student organisation can present their scientific achievements at the Knowledge Fair, another Juwenalia Student Festival that includes the “Great Colorful Procession of Students”, and Otrzęsiny – a ceremony organized is intended to familiarize new students, “some of them shy and a bit lost in a new academic reality”, with student culture and student events, which prove to be the “best remedy for academic anxiety”.

The week begins with a “Field Game” on Monday, inviting students to explore the hidden corners of Katowice while bonding with peers and enjoying the thrill of competition – and is very much based on the Appros we’ve seen on previous trips in Finland.

On Tuesday, the camaraderie continues with barbecues and karaoke nights in each faculty, offering a chance to connect with student reps and engage in games. On Wednesday the Rector’s building transforms into a hub for board game enthusiasts, complete with prizes for the most dedicated players. And it all culminates in Adaptation Day, a cornerstone event that introduces students to their faculty leaders and faculty SU, delivering both info on academic etiquette and student rights.

The student rights thing is enshrined in law too. Another bit of the act explicitly states that student self-governments have a duty to safeguard students’ rights and promote awareness of those rights, as well as giving them the positive duty to act as an intermediary when students encounter issues requiring the enforcement of their rights, and to raise awareness of them through campaigns, workshops, or educational materials.

It’s not so much that every student takes it all in in those early days – although some Polish SUs do do a test after their training. It’s that the SU and its student leaders are positioned clearly as promoters, defenders and extenders of student rights very early on in a student’s experience – in a way that causes students to want to do the job of standing at the front and delivering those messages in the future.

Unhiding the curriculum

Many SUs go further than the rights things too. At the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, the SU has developed nine new student mini-modules which reveal what many here call back home the “hidden curriculum”, important in a country where there are real splits between first in the family students and those with a family history of participation in HE.

Mastering project management is covered in Project at the Start, and building effective study habits is covered in Survival School. In Study Smart Not Hard, students learn how to manage their time, communicate effectively, and excel academically – practical exercises, case studies, and strategies ensure students are prepared to tackle the challenges of higher education with confidence and clarity.

Practical support extends further with modules like How Not to Get Lost in the System, which demystifies the national module/credit/VLE system called USOSweb platform, and First Steps at UAM is a guide to navigating the university’s structure, campuses, and resources. Students are also introduced to the cultural and extracurricular academic activities of Poznań as an academic city, the ABC of Student Government encourages active involvement in university life, and well-being and support take centre stage in Well-being Training and the final module, How to Be a Freshman and Not Go Crazy.

Students gain tools to manage stress, maintain mental balance, and seek (and give) guidance from experienced peers – building a community of student support along the way.

Another aspect of the law are quite strict rules on the disbursement of project funding. In Poland that’s less about funding and maintaining clubs and societies per se, and much more about bidding for and taking part in participative budgeting over activities, projects and events – and means that if a group of students wants to put on a science festival or a community volunteering event, they can get support without having to maintain the “30 people in a group” thing that we cling to in the UK.

The law also provides for state universities to be partially democratically run both at faculty and institutional level – with students given at least 20 per cent of seats and veto power over key decisions like who gets to be Dean or Rector, and what goes into study programmes.

At Silesia, the SU President concluded by turning to the Vice-Rector for Student Affairs to say that “we often argue, but we couldn’t wish for anyone better for the job”. That’s partly because to get elected, she had to command the confidence of those electing her. And it’s partly because him and his colleagues obviously thought they had real power in the process.

He, like all the other SUs we had met in Poland, also mentioned the Ombudsperson at the university as a key figure that students had the right to access – there’s more on that position and why it matters both for student complaints and the thorny issues in Poland’s version of the campus culture wars on the main site.

We’re off on a campus tour now – and will finish up with another bus ride to Krakow, which we’ll explore tomorrow.