In 2023/24, the majority of students from all backgrounds in Scotland were struggling financially.

That’s the standout headline in the Scottish Government-commissioned Student Finance and Wellbeing Study, which examined students’ financial experiences during the 2023/24 academic year.

The results cover income, expenditure, debt, savings, and attitudes towards student finance and support – in a rich and detailed 250 page report that is repeatedly gut-wrenching in its descriptions of the way in which students of all sorts are getting by.

As such, it’s quite similar to the Student Income and Expenditure Survey carried out in England and Wales in 2021/22, but the scope is wider – it covers FE students given Scotland’s tertiary ambitions, and also looks at the impact of finances on students’ academic experiences (including physical and mental wellbeing), identifying groups at risk of financial hardship, particularly those with protected characteristics.

Given the survey was carried out in 2023/24, the £2,400 uplift to the (maximum) maintenance package via the “special support loan” component goes some way to addressing much of the material – even if the touted anchoring to the Real Living Wage was a promise seemingly kept only for one year.

But for part-time students (where there is no maintenance support) there has been no uplift because there was no maintenance support to start with – and the results are just as, if not even more bleak, with full-time study becoming part-time as students spend more time earning while learning.

NUS Scotland President Sai Shraddha S. Viswanathan said:

This study shows that students are struggling in a system stacked against them. It demonstrates clearly that the level of financial support available to students is inadequate to cover the cost of living… this is why it was extremely worrying and disheartening to see no uplift in student support announced in the Scottish Government’s draft budget last week, with students instead seeing an unjustifiable 3.2% real terms cut.

Rent is too high. Public transport is unaffordable. A majority of full-time students are having to juggle work on top of their studies and are still struggling. When students are using foodbanks at rates more than double or triple the general population something is deeply wrong.

Earning while learning

We’ve just published UK-wide material on students at work – and the findings here reflect many of the issues that that work highlights.

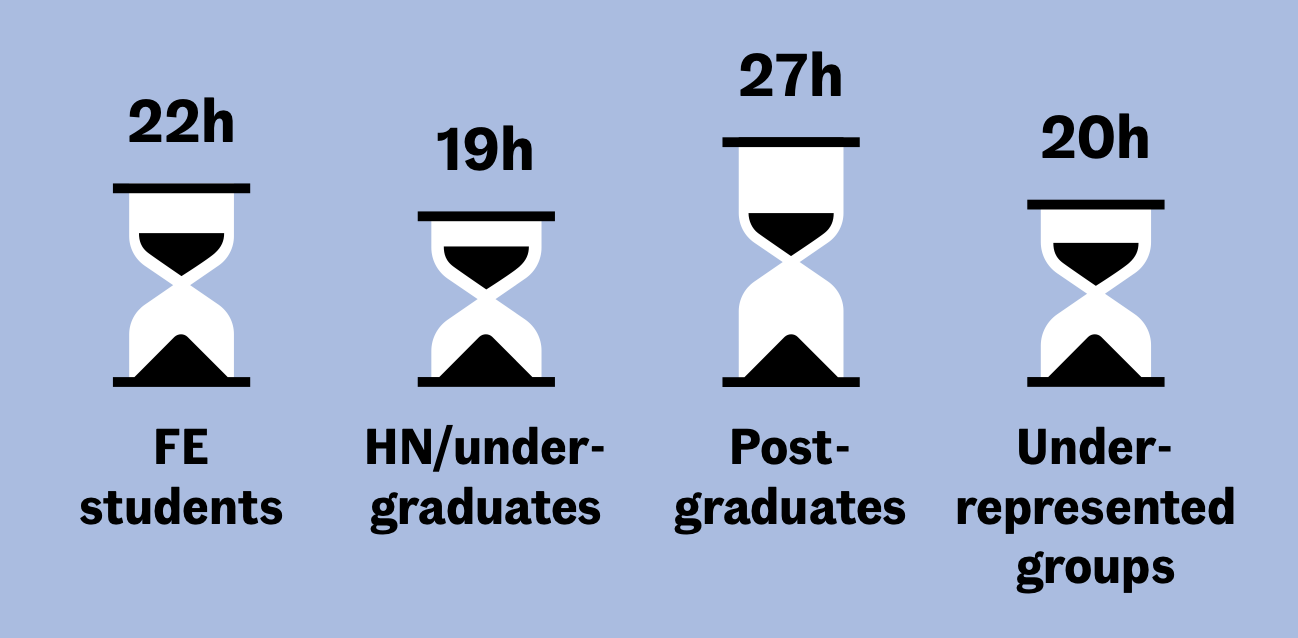

The majority of undergraduates, postgraduates and students from under-represented groups had earnings from paid work during the year – and the median number of hours worked in the previous 7 days for all student groups was above the 10–15 hours recommended – up at a staggering 27 hours per weeks for PGs:

The report reminds us that the Cubie Commission (1999) recommended students work no more than 10 hours per week alongside studying, the Student Information Scotland website suggests students work 10-15 hours per week, and 2017’s Independent Review of Financial Support for Students supported Cubie’s recommendation of ideally limiting work to 10 hours per week during term time.

We’re some distance from all that. Just one in five full-time undergraduates reported working less than the recommended 10 hours over the previous 7 days, almost half (48%) reported working between 10 and 20 hours, 19 per cent worked 21-30 hours, and 12 per cent had worked more than 30 hours.

Again reflecting UK-wide findings, full-time undergraduates from the 20 per cent most deprived areas were much more likely to have worked 10-20 hours over the previous 7 days (63%) than those from the 80% least deprived areas (46%).

Some were unable to take up paid employment while studying – student parents not having access to sufficient childcare, and those with caring responsibilities found taking on paid work more difficult or impossible without support.

Mental and physical health were other barriers to working for students – some students who were disabled or struggled with their mental health discussed the potential difficulties of working alongside education. Others recalled challenges as a result of working – the report says that long hours at work reduced the time they had to study, and those who worked night shifts reported instances where they missed morning classes due to exhaustion.

And for those undertaking work placements as a part of their courses, it was difficult to find paid work which could be based around those course commitments.

A “full set of data tables” are supposed to have been made available as separate supporting documents – no sign of those yet – but we do learn that 23 per cent of UGs were working in hospitality, 21 per cent in retail and 20 per cent in health and social care. It would be fascinating to look at where the other third were working, especially given our findings on differences in treatment between sectors and the demand for on-campus work.

Degrees of debt

Scottish ministers never tire of telling us that students don’t get into debt in Scotland – forgetting that postgraduates very much do, and ignoring that for UGs, four years’ worth of maintenance debt isn’t that far off 3 years of fee and maintenance debt elsewhere.

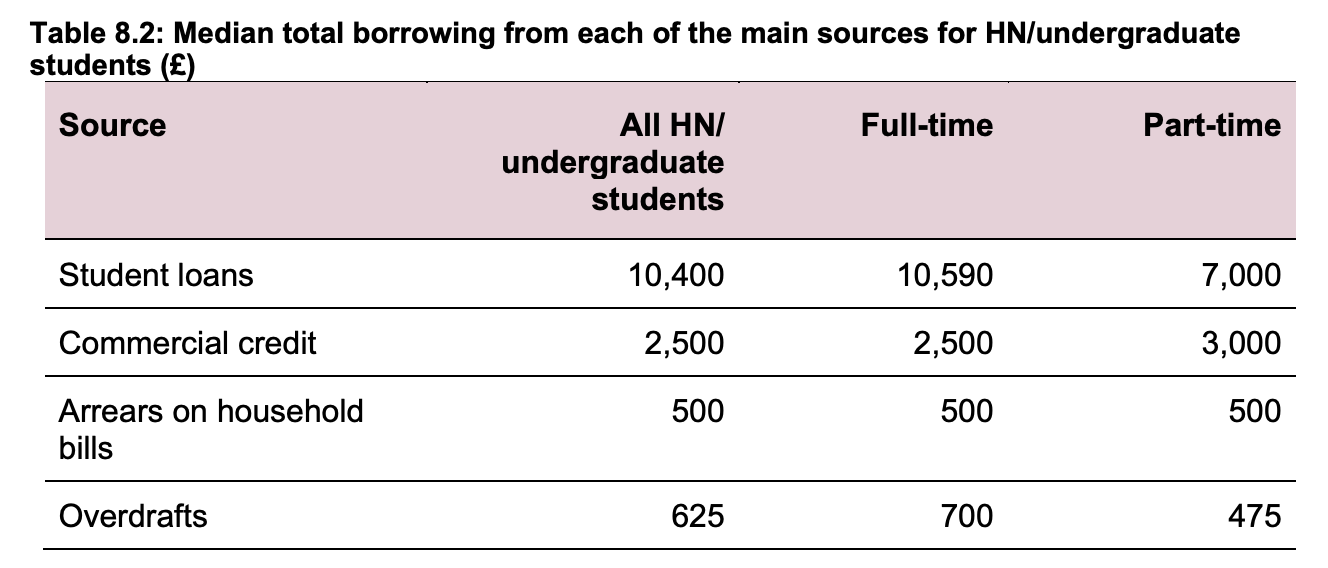

All four nations’ debates over debt almost also always ignore commercial lending – here over a quarter of undergraduate students had borrowings in the form of commercial credit, and (surprise, surprise) those whose parents had experience of HE were less likely to have commercial credit (20%) than students whose parents had no experience of HE (39%).

With no maintenance package on offer, nearly half of part-time students had commercial credit (47%) compared with around a quarter of full-time students (23%).

That reflects wider tolls – between half and two-thirds of students reported experiencing financial difficulty during the year, of them between a quarter and a half skipped meals, and around half of students said financial difficulties affected their mental health and wellbeing “a great deal” or “a fair amount” – with students from under-represented groups more likely to say so.

Mastering an overdraft

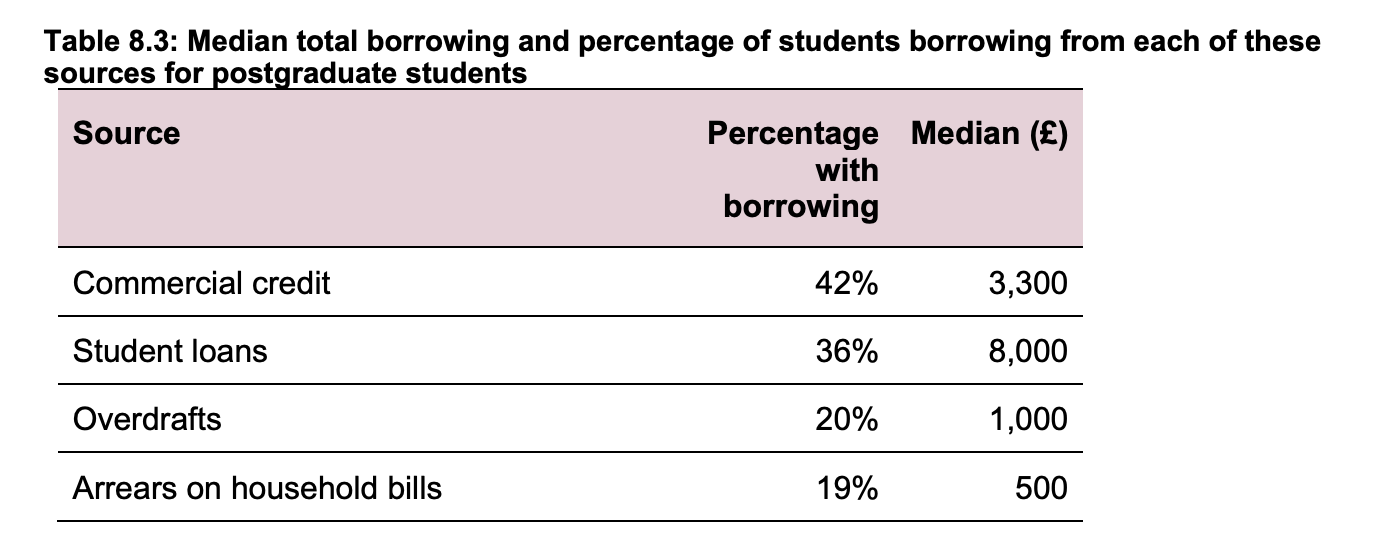

The situation facing postgraduates is especially dispiriting. On the debt thing, 42 per cent had taken out commercial loans, one in five were in an overdraft and a similar number in arrears on their household bills.

It’s not at all clear why the PG loan package has been so poor in Scotland – given the Westminster government seems to make a profit on its PG loans – although that “special support” uplift ought to have made some difference this year.

Between a third and two-thirds of students reported that their study decisions had been affected by the availability of student funding – up at 62 per cent for postgrads – around half of whom used savings or loans to pay their fees.

It’s not a surprise that the loan available via SAAS didn’t cover the entire course fee in many cases – several students commented on how high the fees are and queried whether they provided value for money – and the qual work found that communications from universities regarding late or missed payments were “threatening”, which I’m sure will change as finance teams have a read of the compassionate comms work launched last month as part of England’s student mental health taskforce.

I’m still estranged

One of the other big themes throughout the survey is complexity and access to support.

Student parents, disabled students, and estranged students faced challenges in providing evidence for bursary applications – the volume and difficulty of gathering required evidence were described as stressful, especially for estranged students who often had to repeatedly prove their estrangement despite unchanged circumstances. Students found the process burdensome and emotionally taxing, especially when estrangement occurred during their studies.

Few students with disabilities or long-term health conditions applied for Disabled Students’ Allowance (DSA), often due to unawareness of the support, uncertainty about eligibility, or not needing additional support. Students with mental health conditions or impairments also struggled with awareness and eligibility clarity. Disabled students noted poor advertising of available support and, in some cases, faced difficulties applying due to unresponsive institutional support teams.

Some student parents were unaware of childcare support through their institution or did not need it, while others only learned of it through the research and expressed frustration at the lack of prior awareness. Some relied on informal, free childcare from family and friends, as the available funding did not fully cover childcare costs. They indicated that without family support, continuing their studies would have been impossible.

You get a clear sense that the often baffling inter-relationships between the benefits system, the student finance system and pockets of institutional support are all aspects of state complexity and silo-budgeting, which at the very very least should be subject to more work in terms of simplified entitlement information and application, if not more detailed work on who’s responsible for what.

The free fees thing

This being a piece of detailed social research, the report’s conclusions don’t get into the politics of Scotland’s free (undergraduate) tuition fees totem – but there are all sorts of areas where the researchers end up asking real questions on whether the pot of money that pays for that principle is being targeted in the right way, partly because several of the recommendations are essentially that while support for under-represented groups is there, it’s insufficient.

To the extent to which that might manifest in larger loans, there’s plenty in the report that reminds us that fear of debt is a real issue – but the authors do conclude that the Scottish Government could consider the “balance” between universal and targeted support.

Higher and further education minister Graeme Dey’s quote touts the maximum package of support being up at over 11k, without mentioning that he’s frozen it for 2025:

While this research was under way we have already made significant progress, launching the student mental health action plan and increasing support for higher education students, meaning the maximum support available to students from the lowest income households is the highest it has ever been at £11,400.

Close observers might counter that the number of households able to access that maximum is likely to be at the lowest level ever – given it’s still means tested for family incomes over £21k. He continues:

Along with our firm commitment to free tuition, this is ensuring access to colleges and universities in Scotland remains based on the ability to learn and not the ability to pay. That is why we are seeing a record number of young Scottish students being accepted to our universities, including from our most deprived communities, and why Scotland has the lowest student debt levels in the UK, almost three times lower than in England.

The final line of the 250-odd pages is especially important. We’re reminded that the last iteration of this study took place over 15 years ago – and if student financial experiences in Scotland are to be examined, understood and monitored more closely there is “merit” in conducting this study on a regular basis.

It would be a national scandal in any part of the UK if we had fifteen year gaps between decent data on the general population’s income and expenditure – the complexities of devolution for education with much of the benefits system retained in Westminster helping to drive the intel gap.

If nothing else, and to get us beyond asserting that that new Special Support Loan will fix everything, the Scottish government should commit to annual exercise, and at least announce something on part-time support.