Despite often being accused of individualism and treating education as a transaction, students generally seem to be a pretty fair-minded and community-oriented bunch to me.

Some students on some subjects are more expensive to teach and support than others.

Some need the library more than others. Some use the sports facilities. Some avoid them.

Some will never go near a counselling team – but you don’t often hear those that don’t complain about the resource spent on those that do.

I suspect there’s a few reasons for that. One will be the abject lack of clarity about where the money goes. One of the reasons will be that most use some things/services/spaces, and they get that few use all. Everyone uses something.

One of the reasons is likely to be generational – Gen Xers are just more community-minded than is often implied in the individualism of a self-fulfilment model of education where the goal is to “achieve one’s fullest potential” and get a return on investment.

And anyway – you can see why students might assume that the government is putting in a substantial chunk of money in – even though the long-run real contribution from the state per head is in freefall.

But it seems to me that the web of cross-subsidies, internal choices and diversity of people, subjects and “stuff” can only hang together for so long. At some point, it snaps.

Crackle and pop

Across subjects and pathways, for example, students don’t seem to mind (or notice) that the personal tutor in one area has ten students to support, and in another, five.

But when – within one university – some people actually have one, and others have group tutorials as large as their lectures, the tolerance for the difference snaps.

When providers are doing portfolio reviews, it is indeed often a tragedy that programme X, subject area Y or module Z gets contemplated for closure over recruitment.

But if the way that’s been hanging together is by offering those bankrolling the place through international PGT fees an SSR of 1 to 60, at some point the acceptance of the cross-subsidy snaps.

I’m guessing that the only reason that students down the bottom half of the league table aren’t up in arms about those in the top end having more money to spend on fewer students that need help (despite both paying £9,250) is that the further down the tables we go, the less likely it is that students will have the knowledge or social/cultural capital to be up in arms. Perhaps if they did have it, there’d be a snap.

I was thinking about all of that on a little trip to Belfast for the the European Network of Academic Sports Services’s annual shindig.

Did I say that?

I’m not simplistically saying that this is what happens, but if (for example) you run a function that spends a lot of money on an a small number of elite sportspeople, the rest on kickabouts for home students and nothing on the international PGTs bankrolling the whole place, you may have some strategic thinking to do. Snap.

Following my 90-slide post-HE-Festival thriller plenary, was a superb presentation from the Manchester United Foundation’s CEO John Shiels, who’s been partnering with Ulster University over a project in Derry-Londonderry. It was set up to enhance educational outreach for schools – raising aspirations, improving participation and attainment, that sort of thing.

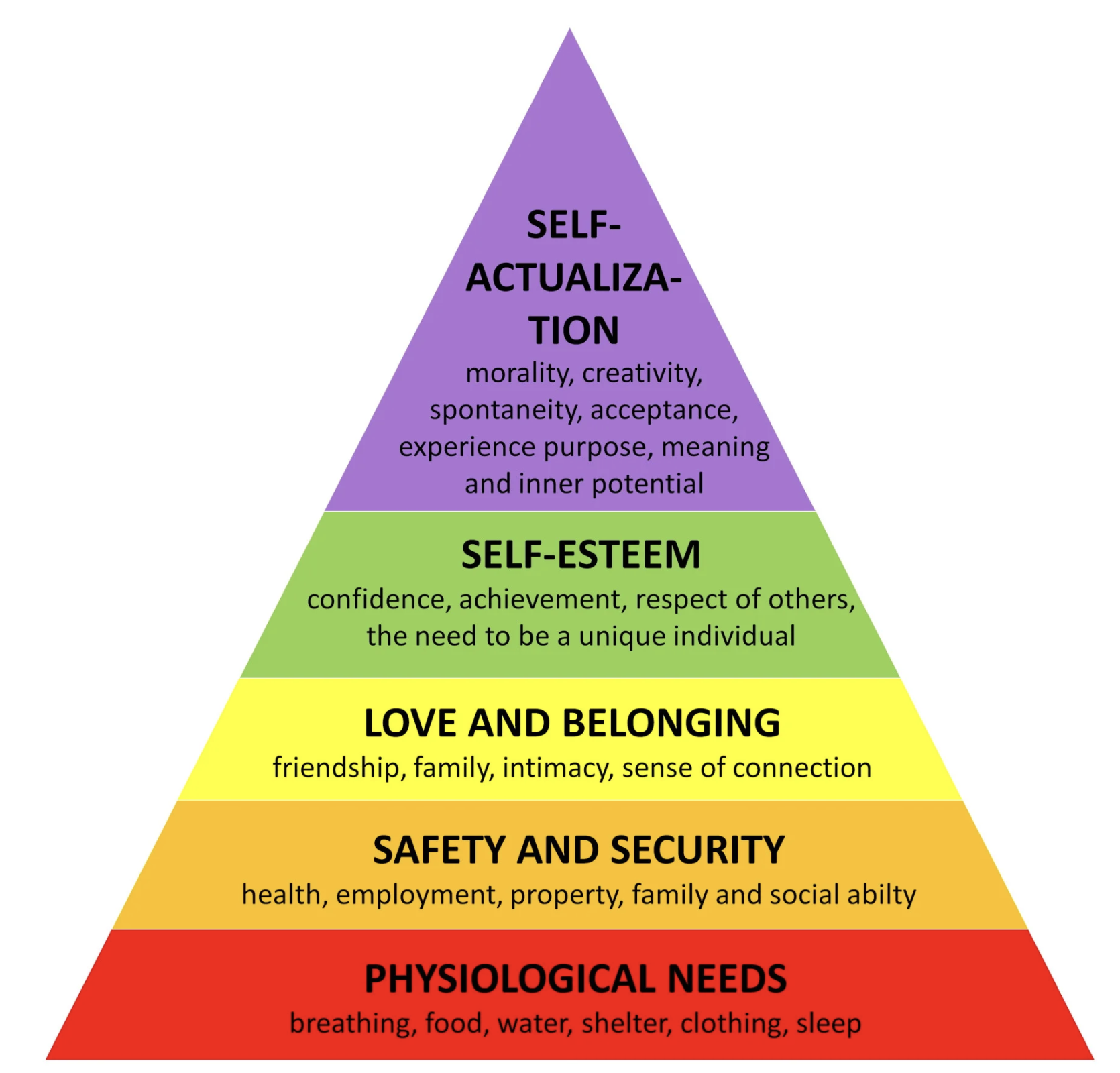

Shiels talked of the way in which he’s had to shift some of the focus of the foundation’s work from self-actualisation in Maslow’s hierarchy to the basics of love, blankets and food. One conference-goer asked if the blankets were Man U branded. Shiels patiently explained that he could buy more if they weren’t – and that would have more of an impact.

I suspect plenty of people think of universities as being in the self-actualisation business – places that never had to think about the 4 levels below, staffed by people that often took levels 1-4 for granted when they were a student. The debate on the Free Speech Act was chock-full of pontification about that purple pinnacle – people just don’t see universities as places that need to do the rest.

And as higher education massifies, and states (right across the West) become less reluctant to pay for the expansion given zero-real growth and ageing populations, it’s hard enough to offer all the self-actualisation on the “unit of resource” – let alone deliberate belonging, or social confidence, or safety, or heating.

All of that is someone else’s job, surely?

The problem is that if you believe in Maslow’s hierarchy as a stacking set of dependencies, hungry students just off a night shift in an Amazon warehouse in a freezing cold house aren’t nattering into the night about the lectures they’ve just been in – they’re tired, hungry and cold.

And being in Belfast at 7am the day after our Festival, I know how that can prevent me from delivering a decent presentation – let alone if I was that tired, hungry and cold all of the time.

Doing all the other bits of Maslow on no extra money or no extra time can feel like it’s too much for students and staff – either because it’s not what people signed up for, or because it removes time for the self-actualisation joys of teaching, research and all of that “meaning and inner potential”.

Boxes and buckets

At the Festival, one of our fantastic student experience panellists talked of how overwhelming “filling the buckets” can be particularly for those without family experience of HE – the academic work, the networks, the work experience, the volunteering and so on.

Not only do you not know how to navigate it all – or which bits are actually valuable – you have less time to get those judgements wrong.

Shiels talked vividly of kids his charity works with with having quite small worlds – the park, the school and home. Multi-million pound sports centres of the ilk the event was held in “look like Disneyland”. But you’re then left with choices. Get people into Disneyland and let them know it’s really for them? Or give them a blanket because they’re cold and then they’ll figure it out for themselves?

Lots of people in other parts of education make the case for the latter. Poor communities are famously adept and resourceful at figuring things out for themselves as long as they’re not scratching around for money for the meter.

One of the classic critiques of Maslow other than its dated pinnacle of individualism and self-fulfilment is that its tiering is faulty. It’s partly why many used to assume that low participation in HE was about a lack of ambition, and why policymakers seem determined to not notice visceral student poverty unless and until it has manifested in drop-out.

But flip that around, and it’s also why our polling work on food and safety and belonging also suggests that focussing there can be more impactful than making seminar slides easier to read, or issuing guides on sensitive language urging people to avoid saying “pet” in the North East.

The real problem is that if the job of educators is increasingly outside of that top tier, we do have to reconsider that cross-subsidy issue.

Me me me

The point about the way we’ve individualised the contribution to higher education is not just that the sector sells unattainable dreams – it’s that it’s sold something to someone.

And as I say, most of those someones don’t mind moderate cross-subsidies. But once you’ve had your heart set on some self-actualisation – and either having to share it so thinly as to make it like a theme park on a bank holiday, or you’re closing the “thing” because it isn’t shared by enough people, you start to feel mugged off. Snap.

Over time, as the fog clears on massification and private contributions, I fear that the room, commitment and case left for collective cross-subsidy melts – at just the point that states want to load more and more of their function onto universities.

It’s all very well for Bridget Phillipson to be demanding efficiencies and better value, but the long-run cost of the teaching and student support end of English HE is currently £3bn a cohort – down from £5.7bn in 2019.

Just how much more efficient – and more Maslowy – can the sector get? And if that involves shuttering the things people who just need Level 5 thought they were paying for, what then?

Put another way, if a very traditional student has paid for self-actualisation – but perhaps in pursuit of the APP, the university is spending its funds on the bottom end of Maslow, doesn’t that at some stage… snap?

As Simon Marginson puts it elsewhere on the site:

…slugging British students in the “student-centred system” even more is outrageously unfair to them – in a higher education that is fully funded by student fees, they have to pay for the public goods generated by institutions and absorbed by society, as well as the private goods they receive themselves.

I said it above – students generally seem to be a pretty fair-minded and community-oriented bunch to me. So if ways could be found – through wider cost of participation reduction and credit recognition (and therefore time allocation) – to make serving others (both students and communities) a core and universal component of the UK higher education experience, we might just be able to maintain the idea that sometimes it’s worth putting food on at the forum – because it makes that forum better for everyone.

That’s the difference between charity and community development. It’s the difference between treating students as children, and adults. It’s the difference between them being consumers and members of a learning community.

The other big critique of Maslow is how “western” and mid-20th century America its individualism and self-fulfilment pinnacle is. When we’ve visited other countries with more associative cultures, forms of student volunteering – for each other rather than the community – seem to thrive.

The generational trends people tell us that Gen Zers don’t fit into Maslow’s pinnacle – they’re in a hyper-connected, digitally-driven world where belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation are intertwined and non-linear. They place a high value on collective wellbeing, social justice, and shared experiences – where self-actualisation isn’t an isolated pursuit, contributes to a larger purpose like equality, sustainability, or other global causes.

And so for me, a doomed and stretched charity model of doing more and more for individuals such that their outcomes are strong conflicts with what they want, and what the sector can afford. A mass system the public don’t want to pay for can’t run that way.

So the more that space and scaffolds are created for students to survive and create together, the less the sector will have to do it for them. The academic society supported to run a study skills session fits the future – pretending there’s enough staff to do it for them doesn’t.

For a long time, in a dated paradigm, the sector was right to build Broadway musicals. But not only does UK HE not have the USA’s HE budgets, nine out of ten Broadway musicals fail. School plays sell out.