Willkomen, bienvenue, welcome…

We’re in Berlin today, but not, regrettably, the hedonistic Berlin of Sally Bowles, Brian Roberts and Baron Maximilian von Heune. Instead we’ll look at a very serious person, whose thinking helped shape the modern university model, and the institution which bears his name.

We need to go back to 1810. The Prussian state was not faring well, militarily crushed by Napoleon in 19 days in 1806. Its King, Frederick William III, sought to strengthen the state, and this included reform of education. He was fortunate in that the director of the ministry of education was Friedrich Wilhelm Christian Karl Ferdinand von Humboldt, known as Wilhelm.

Wilhelm von Humboldt was radical. He implemented a standardised approach to school education across Prussia, with centralised curricula, textbooks and examinations, and a centralised inspectorate. Which all sounds very familiar to anyone looking at English education policy today, excepting the outsourcing of schooling itself to the private sector. And he didn’t stop there: he founded the University of Berlin in 1810, named from 1828 for the King as Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin.

The new university sought to be distinctive. Von Humboldt’s approach embodied, amongst other things, the concepts of lehrfreiheit and lernfreiheit: the freedom to teach and the freedom to learn. This meant that academics were responsible for curricula and for the design of teaching, and were free to pursue knowledge in line with their own thoughts – research driven by curiosity. And for students, freedom to learn meant freedom to shape one’s own education.

These ideals worked. The names associated with the university testify to this. Here’s a sample: physicist Albert Einstein, political theorist Karl Marx, civil rights activist W E B DuBois, philosophers Schopenhauer and Hegel, sociologist Max Weber, physicist Max Planck, poet Heinrich Heine, and folklorist brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. (You’ll spot that this is a very masculine list. Women were not admitted to Prussian universities until 1908.)

The success of the university had a huge influence on other nations. The American university model is based upon Humboldt’s ideals, and you’ll see its echoes in the UK’s notional ideal of curiosity-driven research and in the modular/credit system for organising programmes.

It is not possible for German institutions to avoid being part of German history, and in 1933 the Nazi government turned the university, along with all other institutions, into an arm of the state responsible for propagating Nazi ideals. Lernfreiheit and lehrfreiheit were definitely not in operation; Jewish faculty and other staff were dismissed; the student body was purged; books were burned.

And in 1945 the university found itself in the Russian zone. Which meant more state oversight; still a distinct lack of lehrfreiheit and lernfreiheit; and a name change. While the western powers created the Free University of Berlin, the Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin became the Humboldt University of Berlin, named both for Wilhelm and for his brother, the scientist Alexander von Humboldt.

The Berlin wall came down in 1989, and by 1991 East and West Germany had reunified. (Although like in almost all mergers, it was in fact a takeover of one institution by the other: in this case, of the east by the west.) The university was reorganised and restructured with significant staff changes amongst the faculty: only about ten per cent of the middle-ranked academics at Humboldt university before reunification held their posts a couple of years later. And the university is now simply one within the German system, albeit one that claims the largest medical faculty of any university in Europe, run jointly with the free University of Berlin.

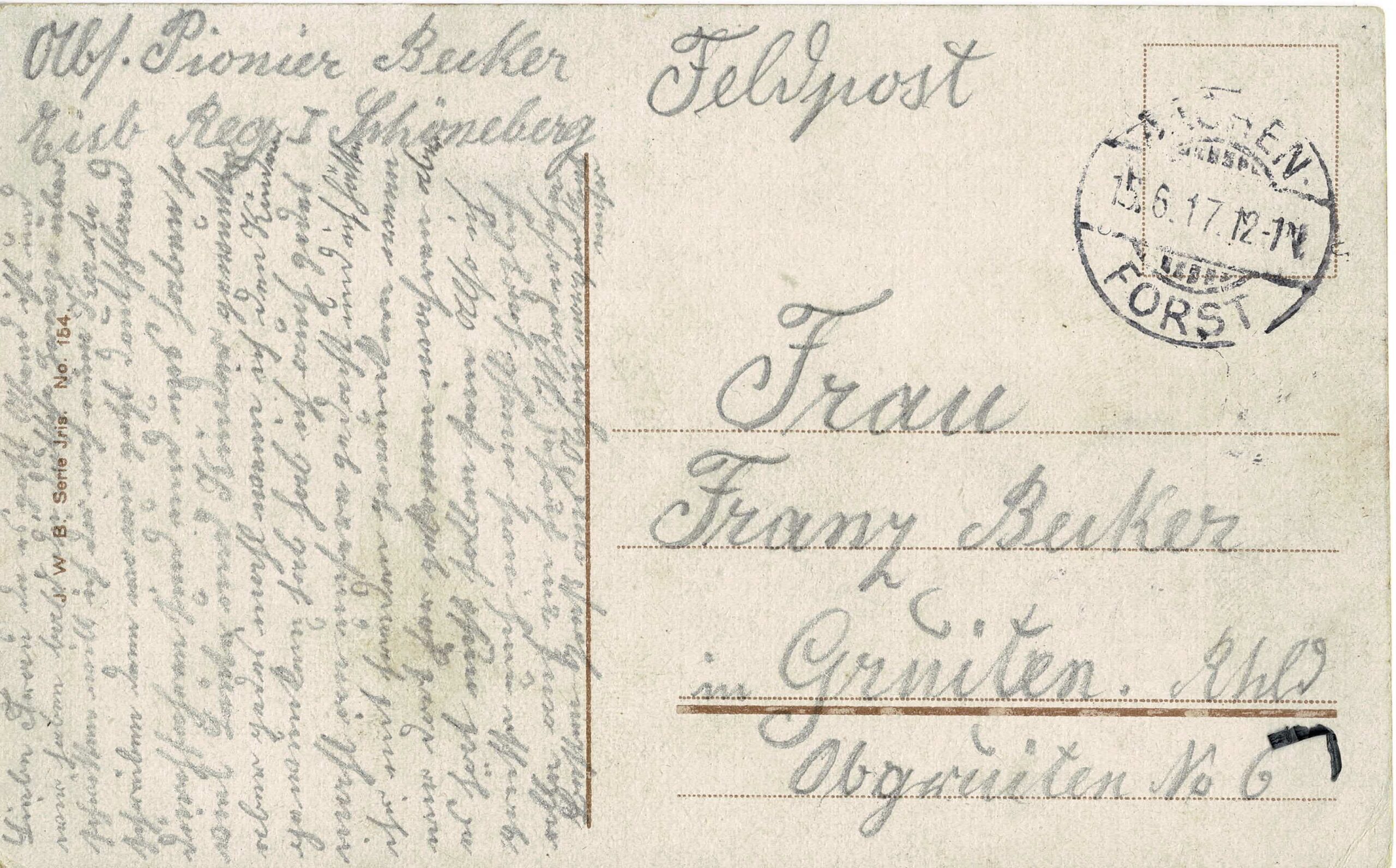

The card was posted on 15 June 1917. If anyone has eyesight and German language good enough to read and transcribe the card I would be infinitely grateful!

Hi Hugh, my son did a year at Humboldt as part of his undergraduate joint honours in German and History. He’s in California now doing his PhD, I’ll see if he can help.