Will better student housing rights reduce housing? It doesn’t look like like it

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

In its evidence to the Renters’ Rights Public Bill Committee, CUBO (the College & University Business Officers) says that in Scotland, where similar tenancy reforms were introduced in 2017, the rental housing market contracted by 12 per cent between 2016 and early 2020.

That, it says, should be concern enough to not give students rights to cancel a tenancy that every other citizen will have.

It quotes the 2016 Scottish Household Survey – which estimated the size of the sector to be 370,000 households. Data released by the Scottish Government in February 2020 then showed 325,649 properties were privately rented – a drop of around 12 per cent.

It’s a number I’ve seen before. It’s quoted in Universities Scotland’s brief on student accommodation, which attempted to argue that it was the “growing regulatory burden” on the rental sector in Scotland that was increasing student housing pressure and increasing costs – it said “institutions are clear that it is supply-side factors rather than demand-side problems that are the biggest driver of current problems.”

Universities UK has used the figure in both its lobbying on the Renter’s Reform Bill in the last Parliament and the Renters Rights Bill in this one. “Some Universities Scotland member institutions estimate that the rental market contraction in their local area over the last two years has been as high as 20-25 per cent” it says, without further detail or evidence.

Unipol bandies the figure around a lot too. It says the decline has “put significant pressure” on university managed accommodation, with “Glasgow University no longer being able to guarantee accommodation for their first year students”, making it “even more difficult for students to apply to a university of their choice”.

Google the figure, and you’ll see it’s a claim that the landlord lobby have leapt on with aplomb.

The problem? It’s nonsense.

It is true that the Scottish household survey estimated 370,000 households in 2016, and it’s also true that in February 2020 the Scottish Landlord Registration System had 325,649 households on it. But every time the Scottish Government has published those figures, it has stressed that you can’t compare A with B – because anything before 2020 was an estimate, and was not being measured in the same way.

The Scottish household survey gives us consistent figures to 2019, and that showed just a 2 per cent drop between the high in 2016 and the last SHS figures in 2019, two years into the reforms. The “drop” is about then using a different method to count – a landlord registration system that was, in the Scottish Government’s own words, “not designed to produce robust statistical data”.

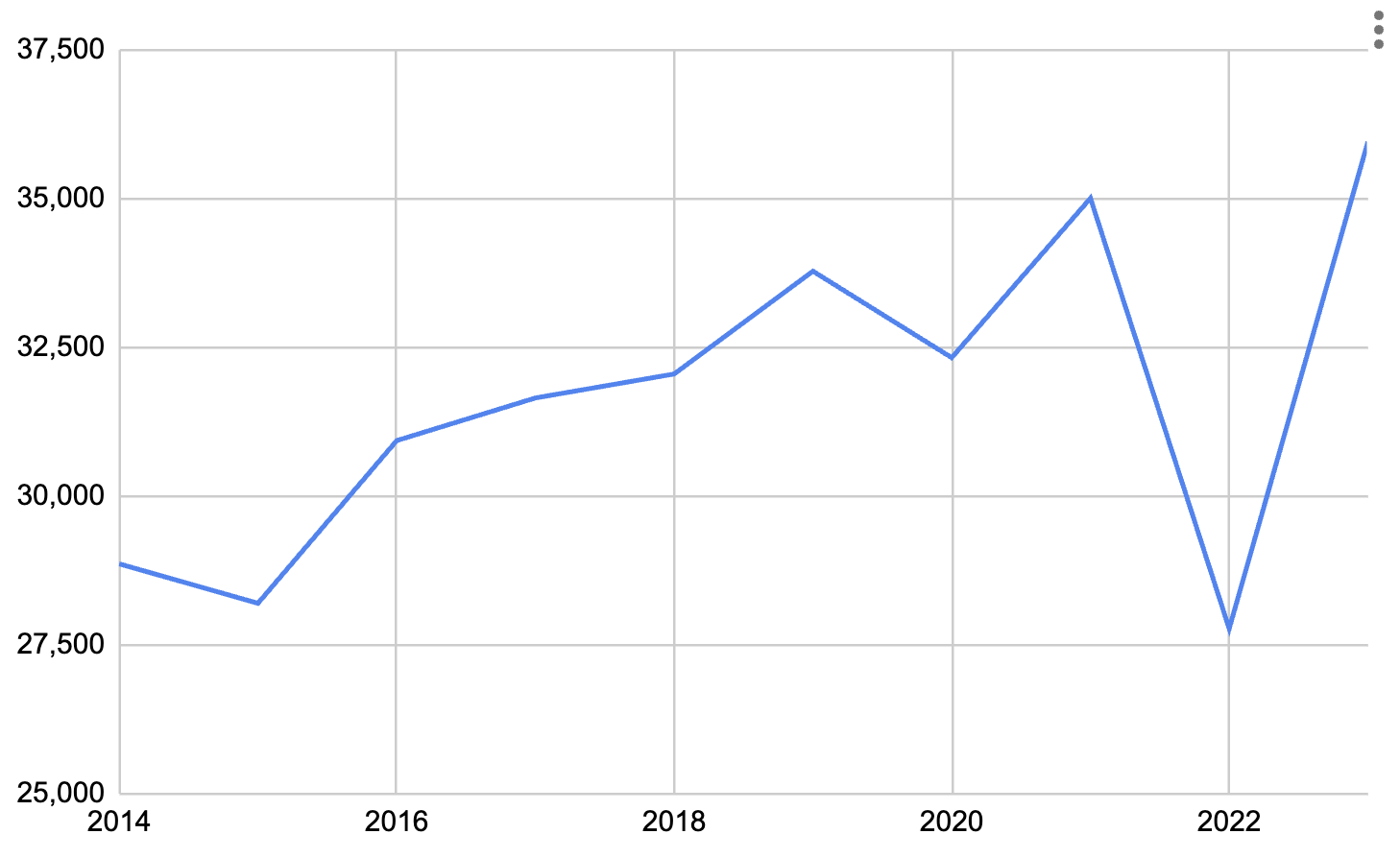

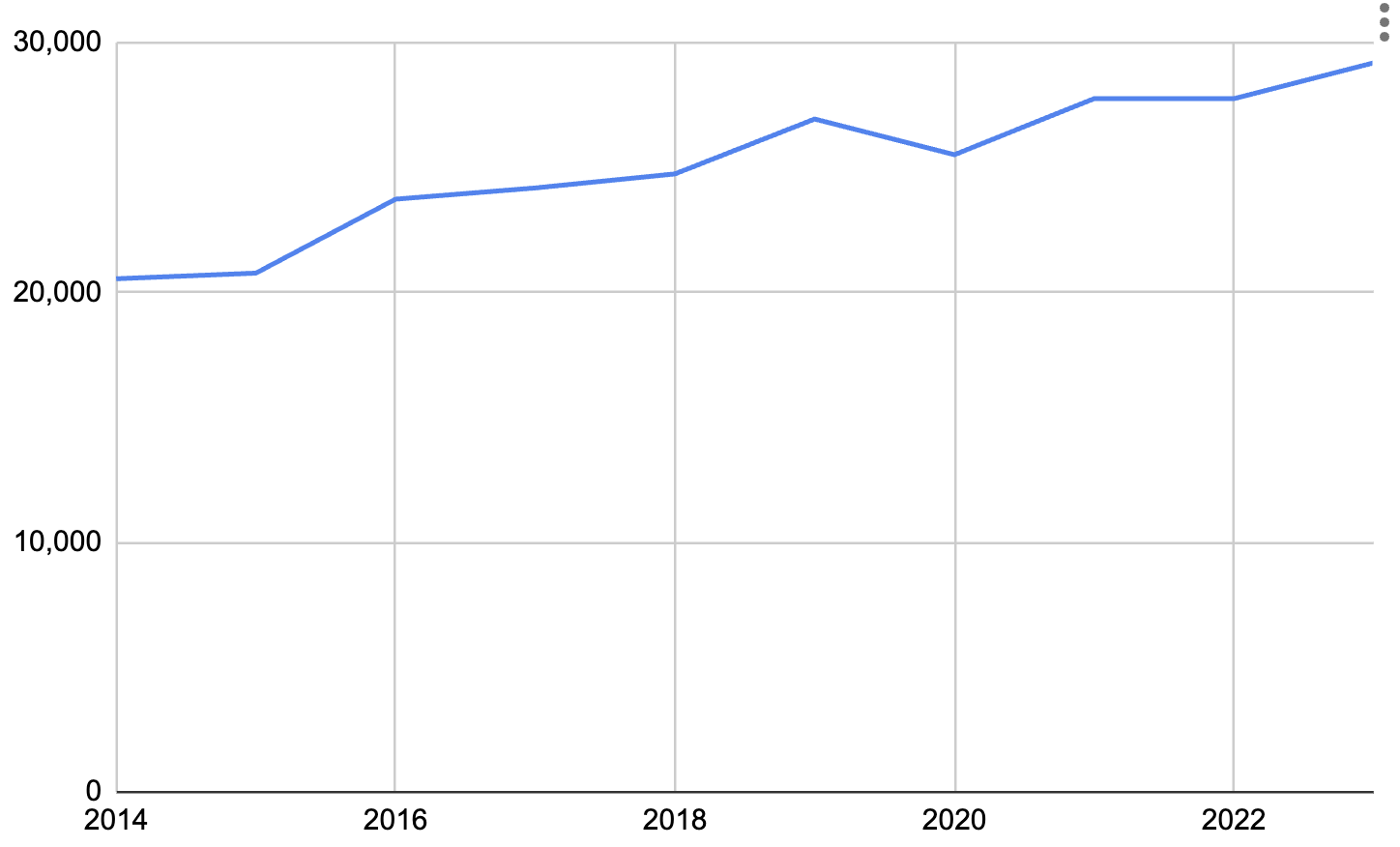

And anyway – that’s the whole of the Scottish PRS. A much more reliable (but inconvenient) source of data from the sector’s POV is the Council Tax base – the number of dwellings occupied only by students. Here’s what that looks like:

2020 was an obvious outlier, and in 2022 there a major admin problem in Edinburgh that meant its official records only show 12 properties that year. Things were bad in the capital, but not that bad. Take Edinburgh out, and here’s what the graph looked like:

As I say, Universities Scotland maintains that “institutions are clear that it is supply-side factors rather than demand-side problems”.

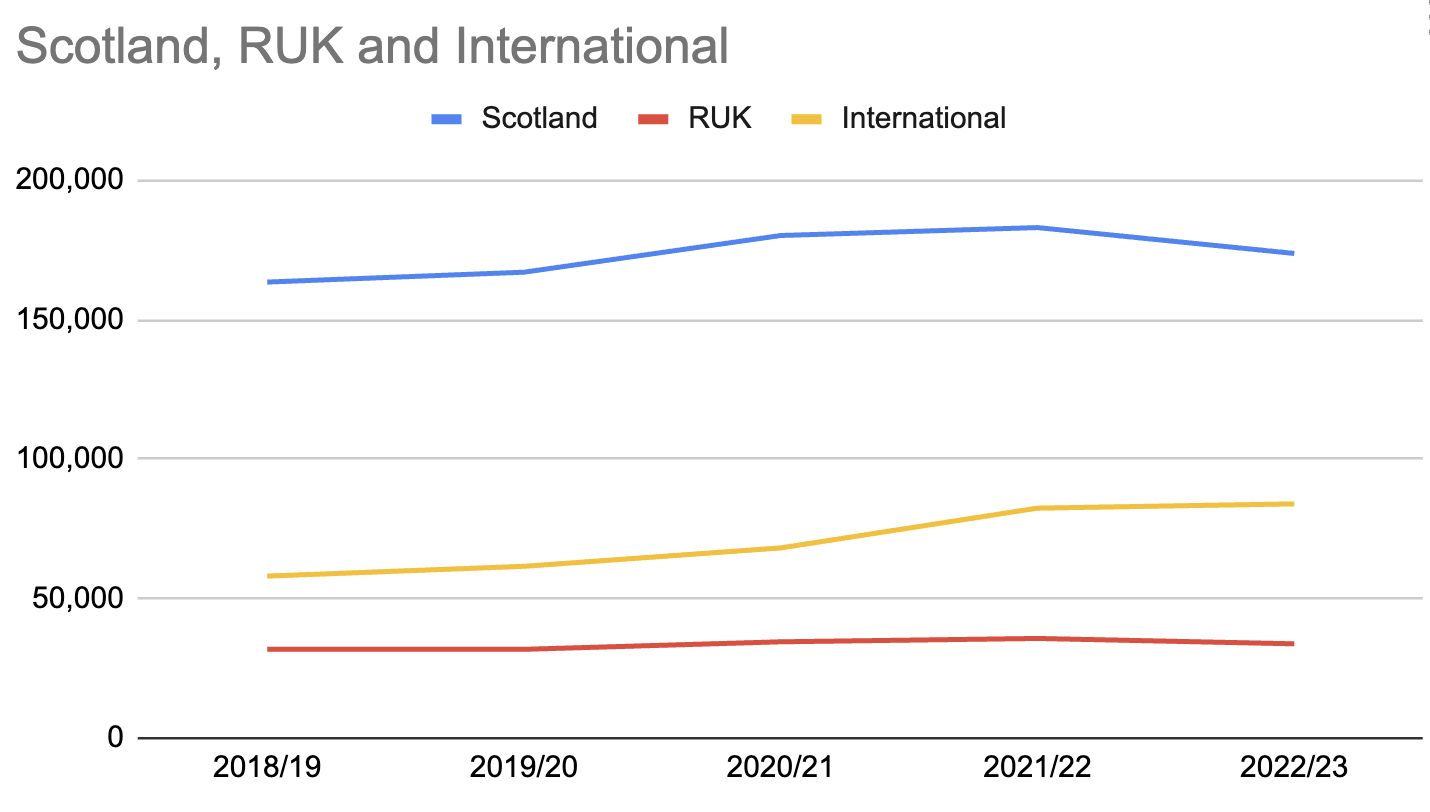

Really? Scotland went from 58,075 international enrolments in 2018/19 to 83,975 in 2019/20. And you know the thing about international students? Unlike a decent chunk of Scottish students, they all need somewhere to rent.

The debate over the Renters’ Rights Bill is an important one – because we could be on the verge of robbing students rights that everyone else will have based on the argument that supply will collapse, “evidenced” from Scotland.

It would help if those representing the sector with “evidence” checked their figures.

Excellent post. One also needs to remember that around one in three HE students in Scotland are registered in Colleges on full time HNC (1 year)/HND (2 year) courses. These are not part of the “University sector” and not included in either UCAS or HESA data exercises, therefore frequently ignored even though many have full articulation into second and third year of four year honours degrees at university. Most College students live at home, the first year of HND (often leading to HNC) and undergrad degrees being broadly equivalent to Upper Sixth/Year 13/old “A2” in England’s school and college system… Read more »