In September Universities UK (UUK) President Sally Mapstone opened the annual gathering of vice chancellors with the warning that the UK’s universities face a “fork in the road.”

One path, she argued, leads to deterioration and decline of a once-great national asset. Alternatively, she continued, a programme of national higher education renewal, with government support, could support the sector to continue to deliver for the nation in the decades to come.

Her remarks reflect a growing consensus that, while the nature of the headwinds faced by the sector in disparate parts of the country may differ, there is a common thread of challenge to the sustainability of the current model of HE.

While policymakers may agree in principle on the value and importance of higher education, they may question whether a system originally designed to cater to the demands of an academic elite is sufficiently geared up to support a move towards near-universal participation – or even whether such as move is possible or desirable if it is going to mean continued growth in costs. Former Sheffield Hallam vice chancellor Chris Husbands has summed up the core challenge in a recent pamphlet for HEPI: “successive governments have called into being a large and diverse higher education sector but are reluctant to provide the funding and policy framework in which it can thrive.”

Higher education, and the institutions that deliver it are, quite simply, very expensive. There is a strong argument for public investment in higher education, when you look at the economic returns from education and research – estimated most recently by UUK at £14 of impact per £1 of investment in 2021-22. Likewise there is a strong argument for contributions in some form from employers, who benefit from graduates’ skills, and from graduates, who reap rewards in their wage packet. But government, students, and employers need to be convinced that the investment is worth it – that funding is being invested in the right things and that the value generated is reasonably consistent and sustainable.

There is a realpolitik in a calculation that in times of economic challenge universities must offer up the prospect of making efficiencies, and being open to reform, as part of a notional quid pro quo of securing continued public investment. There is, however, a more exciting way to think about the current policy moment as an opportunity to push thinking beyond the mundane – as a time when the window is open for more radical and innovative thinking that has the potential to unlock genuinely positive change.

The sector in England has a sympathetic government in Westminster that seems to have fundamentally accepted the premise that the sector is struggling for funds, and to recognise the critical importance of engaging universities as partners in its core missions, especially on economic growth and opportunity. There is also a cultural shift in train in that the Labour government’s underpinning theory of change is that partnership and collaboration can be powerful mechanisms for achieving desirable public policy ends.

The government has not yet said how it intends to achieve its ambitions or what role it wants the higher education sector to play. The industrial strategy green paper actively seeks input on what needs to be done to kick-start equitable economic growth and solve the productivity challenge. The Budget, aside from sustaining investment in research and innovation, was silent on funding for teaching and university financial sustainability, although it seems feasible that the freeze on undergraduate tuition fees implemented by Teresa May will be allowed to lapse, permitting fees once again to rise with inflation. While indexation of fees to inflation would provide some moderate measure of relief to the sector it would not be sufficient to address long term financial sustainability.

All this opens up the possibility and the necessity for thinking more strategically about opportunities to do things differently through scaling up collaboration in higher education.

Seizing the moment

In any strategic discussion about the future of the sector the question of possible mergers and shared services arise – but typically just over the horizon and somewhere else. But we have also observed a shift in the mood music. As universities manage financial sustainability in the here and now, there is an increasing focus on medium to longer term solutions alongside the more traditional efficiencies. The conversation had moved beyond “doing what has always been done more efficiently” to looking outside the walls of the individual institution. These perennial conversations on shared services, outsourcing, mergers and more structured partnerships are once again on board agendas.

This shift is illustrated in Universities UK’s “blueprint” for Labour’s higher education policy Opportunity, growth, and partnership which proposes that Universities UK should lead “a transformative programme of work which will bring our members together to share learning and good practice in relation to efficiency, transformation and income generation; and explore options for additional regional or national shared services.” Efficiency in its best sense is not the pursuit of cost savings for their own sake but the strategic deployment of available resource in the pursuit of common goals and shared value. When funds are tight, that is when partnership, collaboration, and pooling resources can be a critical means of achieving organisational strategic objectives, and realising more value than can be achieved when acting alone.

In 2019 our report Future proofing the university exhorted the sector to “fix the roof while the sun is shining” – pressing for these long-term collaborative activities to be put in place while there was time and space (and potentially funding). But by their very nature discussions about new partnerships and collaborations are complex, need one or more parties involved and rarely progress (with some notable exceptions) beyond warm words and an openness to exploring. And amid the pressures of delivery in pandemic conditions there was scant bandwidth in institutions to seek opportunities for major transformation. So maybe we got it wrong – maybe now is the time to make necessity the mother of invention, face into the headwinds and use them to drive some more fundamental change across the sector.

Rather than taking “efficiency” to be another way of saying “cuts” it makes more sense to start with mission and strategy – from an institution perspective, what are we trying to achieve here, and could we do it more impactfully through operating at greater scale, coordinating or even combining with other institutions, or forging new partnerships? This starting point acknowledges that higher education institutions do not merely exist to make themselves successful but to serve their communities, which may start at their doorstep, but can extend across the globe.

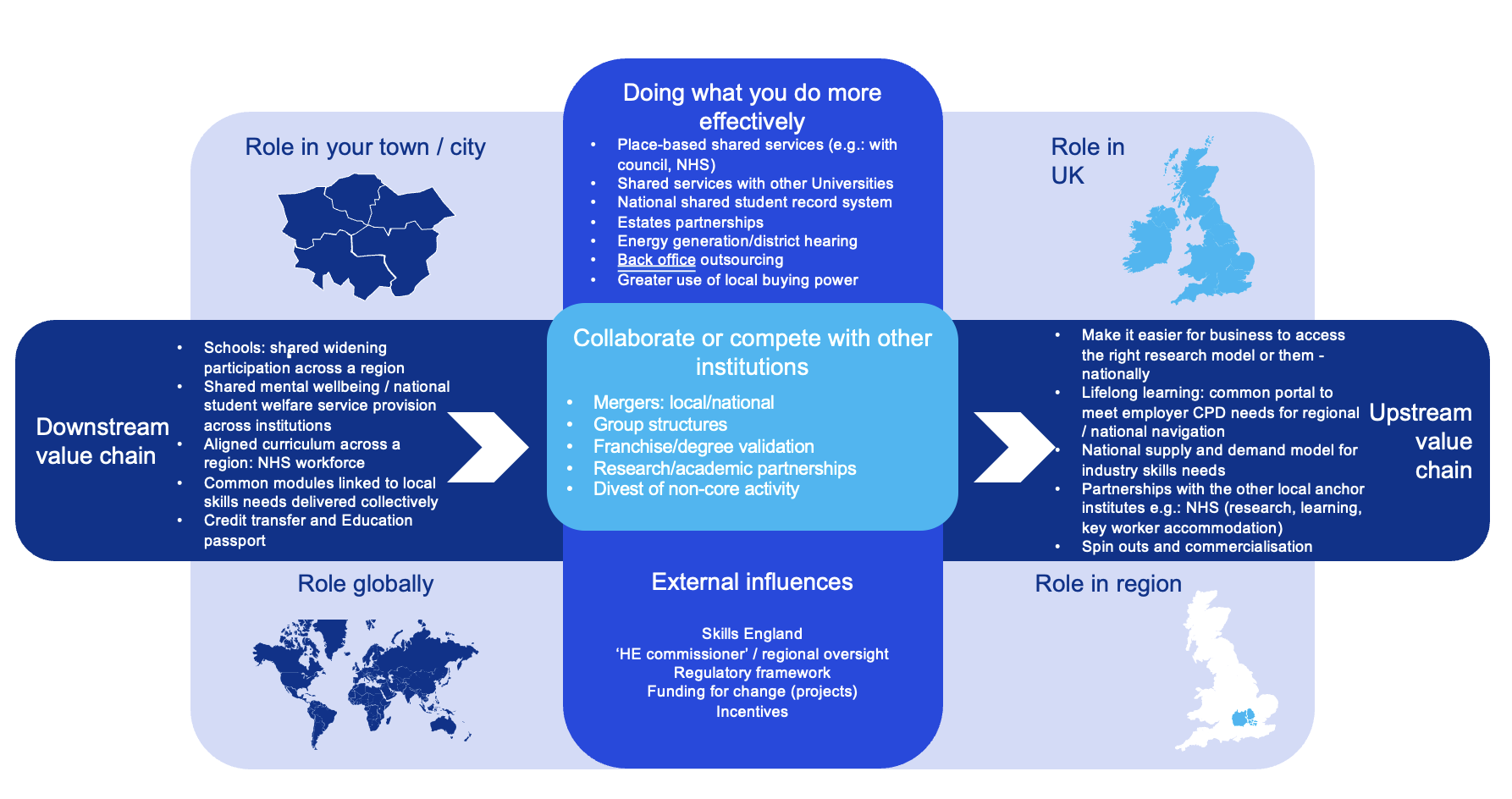

A framework for exploring opportunities for novel approaches to achieving higher education institutions’ missions. Source: KPMG

Seen from a macro policy perspective the equivalent question is which shared policy goals might be more efficiently and impactfully realised through coordination? One way of answering this is to look at the system as a whole and where there are similarities in practice that could (with a bit of persuasion) be replicated or outsourced to a third party to save endless reinvention of wheels. Another is to look at the system from the “outside” – see the sector through the eyes of the prospective student, the business or employer, or local or regional policymaker, and ask how they can most easily and seamlessly get what they need from the system to achieve the wider goals of education access, economic growth, regeneration, public sector productivity, decarbonisation, and so on.

There are multiple forms that collaborations can take. Some are quite well established, like shared services – at sector level UCAS, Jisc, and the sector’s mission groups are at core a form of shared service. The sector has also seen some mergers or incorporations of a smaller institution into a larger one, in particular circumstances, and it’s an open question whether more of these might be on the cards. Franchising arrangements, outsourcing of services, and use of agents are all also common practice, though require careful management. There are international examples of higher education institutions adopting a more federated, networked or consortium structure such as the KU Leuven Association in Belgium or the New Hampshire College and University Council in the US, as well as the much-cited California model of HE.

There are a whole range of structural and cultural barriers to collaboration – shared services being subject to VAT is often cited as a reason for not doing it. There may be a requirement for upfront investment, or proposals may be considered overly risky by boards of governors if the returns are uncertain. Organisations may exist in proximity to each other and have goals in common but be so culturally different as to be unable to find a shared way of working or even to spark a level of animosity. Nobody should underestimate the challenge of managing institutional costs in times of financial pressure, and the impact on leadership bandwidth, or the preparedness of institutional staff to get behind proposed new initiatives. The ideas have to be sufficiently compelling for the work to be done to overcome these barriers.

Yet the fact remains that the higher education system as it stands, however beloved, was not set up to respond to the contemporary political, societal and economic environment. If we continue to try to build radical change within the framework and institutional boundaries we have, we will fail to deliver on the potential of the sector. We need to think not “why it is hard” but “what needs to be true in order for change to be realised?”

Testing the premise

In early July, Wonkhe and KPMG brought together a carefully selected squad of higher education sector and institutional leaders, thinkers and strategists to engage in a structured discussion about opportunities for a more radical approach to pursuing efficiency through collaboration. We wanted to see if it was possible to startle ourselves out of the usual conversational grooves of “nice idea but too hard” and collectively generate some big ideas that could give some shape and momentum to discussions about sector transformation and long term sustainability. Our aim was, by approaching the conversation in a collaborative manner with the right people engaged, to move beyond the warm words and theoretical and into the practical across a range of options.

At the start of the day we asked those involved to tell us what “radical efficiency” means to them; with answers including “trying something new that is more than tinkering around the edges,” “innovative change to deliver more for less,” “a new norm that relies on us developing a new muscle; a real need to prioritise our efforts and focus on outcomes,” and “breaking the mould; ceding control; being bold and strong leadership.”

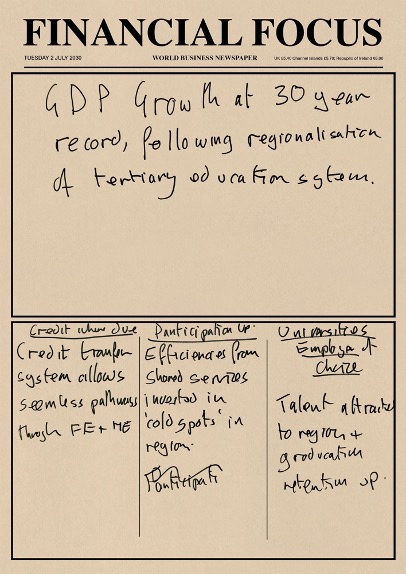

The purpose and mission of the sector and its institutions was never far from people’s minds – given shape by an exercise that asked attendees to generate a potential future if the sector gets this right, via the mechanism of a 2030 media headline.

A speculative headline: “GDP growth at 30 year record, following reorganisation of tertiary education system.”

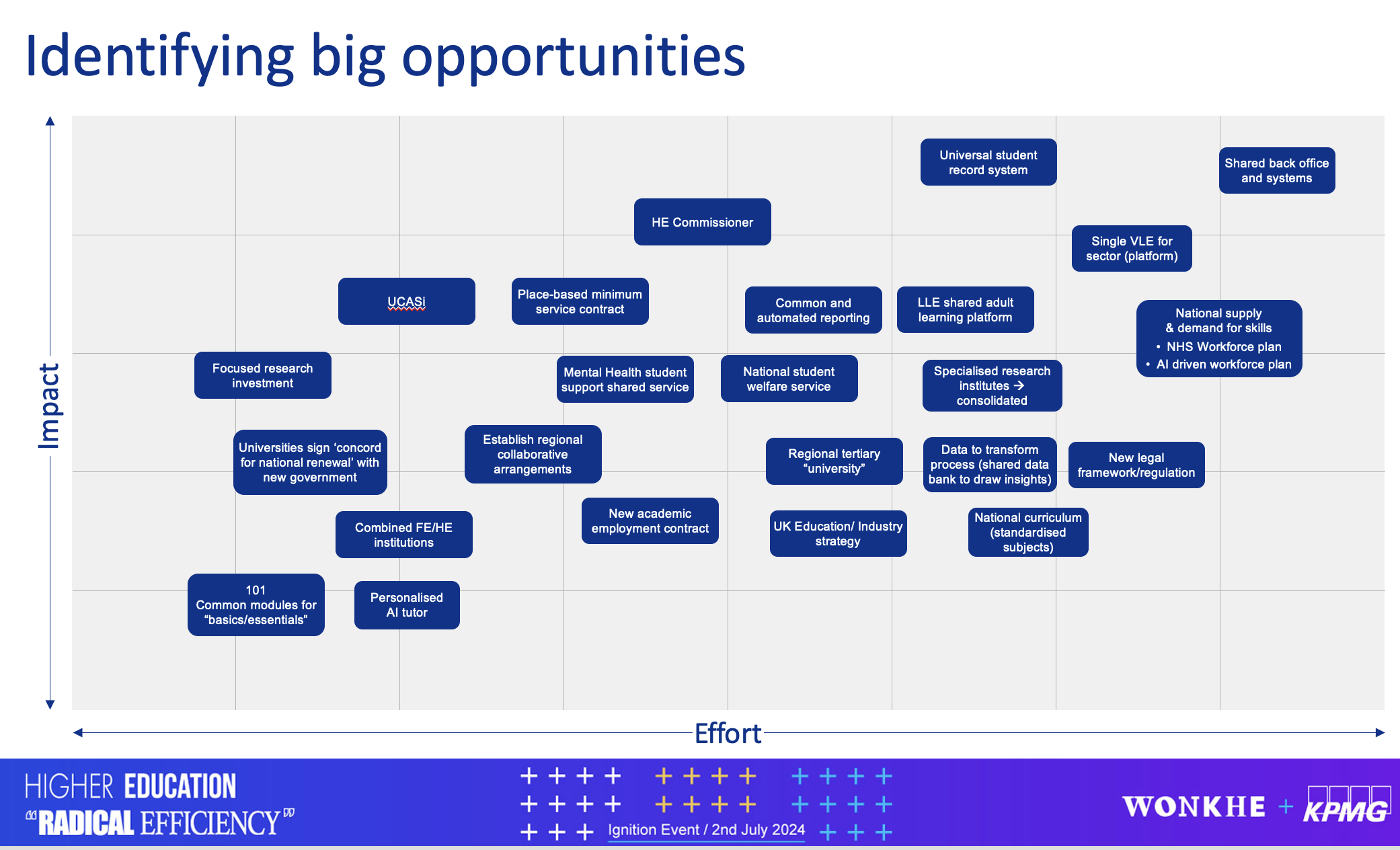

The group came up with a whole batch of ideas, listed below – including a “national higher education curriculum” which we doubt would be universally popular. But in terms of workable solutions there was a degree of consistency across the discussion coalescing around three areas for further development; areas we will be exploring further in the weeks ahead:

- Student passport and credit transfer: how to actually deliver on the promise of flexible learning pathways for everyone across levels and institutions. Credit transfer is a nut that needs to be cracked collectively to unlock the wider potential of flexible learning, meeting industry requirements and lifelong learning. The will, the technology, and the policy instrument in the form of the Lifelong Learning Entitlement are there – but this agenda needs leadership, consultation, and funding.

- Back office, systems and digital alignment across a range of areas. This is unsurprising when we raise the question of shared services that this is a perennial issue, and there is no shortage of reasons why it is not possible, from VAT to the distinctiveness of specific institutional needs. But it’s not impossible to imagine, say, a “no-frills” student record system that serves the core need of collecting student data and HESA returns, that could exist as a lower cost option in the market alongside the more bells and whistles products.

- Regulatory change to accommodate a more collaborative approach, with the suggestion that an HE Commissioner should be appointed to act as a convenor for new forms of collaborative activity – acknowledging that for change to happen there needs to be an outside force that makes it happen, and that brings a level of independence and also potentially policymaker attention and funding.

The full list of ideas and opportunities generated, mapped by effort versus impact.

Running through these three areas for development is the potential for greater regional collaboration, in ways that allow for a more efficient and coherent provision of education opportunities, that are more closely aligned to growth agendas. Regional collaboration meets the criteria of both radical and feasible to achieve. National coordination tends to require significant convening power, funding, and government policy change to accomplish and is not always successful – think national credit transfer framework that successive governments have said they want and none has been able to deliver – whereas regional collaboration could potentially be achieved with more modest interventions, and a smaller table to fit everyone around to work on the details. There are opportunities to look at sharing beyond the back office, such as curriculum, student welfare, and widening participation – even before you get to the University of Somewhereshire federated model.

There are also clear external beneficiaries of regional collaboration in higher education in the form of learners seeking access to opportunity, employers seeking graduates, industry seeking innovation partners, and policymakers seeking good outcomes for their region. As English devolution takes shape, and the government seeks to realise its ambition to achieve growth across the country and tackle historic inequities, collaboration could offer a way to serve regional growth agendas more strategically.

Looking at the HE system from the other end of the lens – a prospective student looking for education opportunities in the area, or for access to a specific service, or an SME director looking for ways to upskill their workforce on AI – illustrates the extent to which the system is not currently set up to meet users’ needs. Rather than institutions chasing the same pots of CPD revenue or commercial income, or developing the same kinds of courses to compete for the same pool of students, a more coordinated and less zero-sum approach could open up ways for all to succeed.

This article is published as part of our series on Radical Efficiency, in association with KPMG.

The WONKHE team reference to regional collaboration is interesting but thin on the need to consider the conjoint development of UK places – towns, cities and regions. I emphasise conjoint because a fundamental UK weakness over the past century has been the fact that higher education and territorial development policy and practise have operated in silos. More specifically, there has been no government steering of the geography of HE – what is researched and taught to whom and where – at the same time as the UK has faced widening regional as well as social disparities. This is perhaps why… Read more »