Almost as soon as it was launched, Health Secretary Wes Streeting’s Change NHS ideas platform was flooded with “amusing” suggestions.

They included a partnership with Wetherspoons to put a boozer into every hospital, renaming the NHS to “NHS-y McNHSFace”, making Boris Johnson pay the £350million a week he promised on the side of a bus, mandatory clapping for NHS staff, and renting out cinema seats:

Cinemas need a boost – often empty post pandemic. We need hospital beds. People like films. People have mental health issues. Solution – the NHS rents out empty seats in cinemas so people can watch a film whilst they’re waiting to be seen or under observations. Win win?

For some on the socials, the public consultation “shows what a stupid idea citizens assemblies would be”.

I’m not so sure. The whole point about citizens assemblies is that it puts people in the position of making the same sort of trade offs that policymakers have to make, rather than imagining that the problems are all about a lack of “ideas”.

The SUs that have implemented similar “ideas” based platforms into their democratic structures have also tended to find that they can be home to a very broad range of ideas – and rarely consider complexity or trade-offs in policy making.

When it comes to higher education and students, there’s a whole clutch of suggestions up already. There’s plenty, for example, on the student finance situation for student medics, nurses, midwives and other professions – with everything from increasing bursaries to sorting expenses out and free fees in the mix.

It’s hard to disagree with this:

Reduce fees for nursing and midwifery students as they DO contribute to the workforce in spite of nominally being supernumerary and reintroduce part of clinical practice being rostered for which they are paid a stipend.

And the complete failure of the DWP, the DoH and DfE to sort messes like adequate childcare funding for full-time students also comes up in ideas like this.

Won’t somebody think of the students

But so far, apart from various submitters (including me) suggesting that full-time students be allowed to register with a GP at both their home and term-time address (because not being able to do so is a huge nightmare for all sorts of reasons), there’s not a lot in there about students in general.

I’m very much hoping that both universities, SUs and readers chuck in some serious suggestions, and that the sector bodies respond to some of the other consultations on the site – partly because the intended shifts all have the potential to involve students and universities in different ways:

- Shift 1: moving more care from hospitals to communities

- Shift 2: making better use of technology in health and care

- Shift 3: focusing on preventing sickness, not just treating it

To the extent to which we might see students as a defined community, I’m certainly looking forward to mid-November, when the DoH will provide a “workshop in a box” to support organisations to gather insights to help develop the 10 Year Health Plan:

Engagement builds on your expertise of engaging the public, staff, under-represented groups, and stakeholders allowing you to share existing and future insights.

I threw up my own thoughts on the ideas site the other day. As well as the GP issue, I’ve argued that student costs re medication are not covered by student loans – they should be free as in the rest of the UK. And disability screening delays in the NHS literally close off access to university or adjustments required at it – these should be guaranteed.

Meanwhile, listeners to the Wonkhe Show will know that I’ve taken a special interest in Finland – and graphics like this. I should explain.

TB or not TB. In Helsinki

Back in the 1930s, Finland and its students had a tuberculosis problem. That inspired Göta Tingvald, a doctor in Helsinki, to start TB screenings for students – and that did two things. It revealed to policymakers the true extent of the prevalence of TB among students, especially those from rural areas. And it ensured that students were able to access early treatment.

So successful was the initiative that the Finnish NUS (SYL) became involved in establishing a broader student health service model to go beyond TB screenings. Its committees proposed a comprehensive health service for students, including medical check-ups, a central research function and campus provision. By the 1950s, that all culminated in the formal establishment of YTHS – a student health service funded partly by government, and partly by compulsory fee.

I’m not, for the avoidance of doubt, suggesting that that sort of model would work or should be recommended in the UK – radically different cultures of health insurance apply here. But the NHS is one of the few public services where there’s comparably (and in some cases higher) spend from public funds. What’s missing for me is any focus on students as a group.

The model in that graphic above, the realities of the ever finer lines being drawn between universities and the NHS’ responsibilities (especially over mental health), and the desire to push responsibilities towards communities all make the case for students not as an especially deserving group, but as a group with a distinct set of health challenges and a distinct need for a dedicated strategy and set of services.

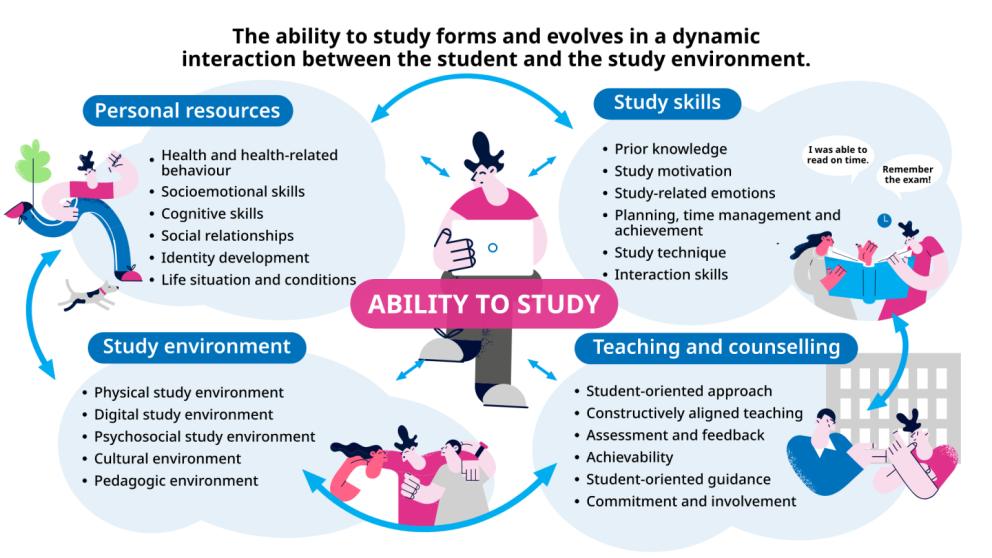

The guiding model for “ability to study”, developed by the Finnish Student Health Service (FSHS) and the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, gets across various factors influencing students’ ability to do well – and provides guidance on how HE communities can promote it. The whole point is to integrate, not separate, healthcare with academic support – and stresses the importance of collaboration with and within universities.

Students are an important part of it too – they’re naturally on all the boards, but even at the individual level the model imagines that a student’s personal resources and skills interact with the study environment and quality of teaching. There’s also advice for staff (both teachers and student support staff).

That might all sound very well, but there’s some practical aspects that shouldn’t be beyond us.

KOTT to get and get again and again

The Finnish Student Health and Wellbeing Survey (KOTT), carried out once every four years, produces hugely valuable data on the health, wellbeing, study abilities, and health services for students and any changes that might be needed in the policy environment.

This year’s results have found that “psychological distress” among students in Finland has decreased from 35 per cent to 29 per cent since 2021, with a significant reduction among women. Diagnosed anxiety and depression rates remain high though – with 23 per cent of women and 10 per cent of men diagnosed with anxiety, and 18 per cent of women and 12 per cent of men diagnosed with depression in the past year.

That’s partly about money – 19 per cent of students are experiencing very scarce and uncertain income, 24 per cent of students report food insecurity, and 18 per cent have had to compromise on prescriptions due to financial constraints. That really is stuff we need to know in the UK a lot more than we need to know the tiny movements in NSS scores each year.

But it’s not just about the service, the app, the integration with universities, the debate over the therapy (counselling) guarantee or the way in which the Finnish version of Student Minds has a focus on community building and belonging through student tutoring.

Particularly important in all of it is the health screening strategy when students arrive at university – a process that helps students and healthcare professionals check a student’s health status and refer them to appropriate services as early as possible at the beginning of their course.

The HealthStart questionnaire examines physical, mental and social health, as well as key aspects of a student’s health behaviour and factors affecting their health and ability to study. If answers indicate a need for an appointment, they are referred to an in-person or remote consultation straight away.

That in and of itself is preventative, locates health in an educational context, puts an appropriate reliance on students to take responsibility for their health before a worsening reduces that agency and provides valuable intel for universities. But crucially, it also provides killer intel on the relationship between health and study outcomes.

Once you have a huge number of health questionnaires filled out, you can track outcomes and look for links longitudinally. Initial motivation and mental health is the sort of stuff people assume – but this paper found that daily smoking in women and severe obesity and/or drug use in men were particularly linked to lower graduation rates.

That has allowed the health promotion functions of the service and that Finnish version of Student Minds to design specific peer-led interventions that can be rolled out by universities and their SUs. Other papers have mined the data for lessons on everything from teaching and assessment strategy impacts on health to students’ preparedness to take their health seriously and its relationship to study success.

Come on come with me to the place to be

Health matters – and it goes beyond spiking, mental health and the cliff-edge at 18 after a collapsing CAMHS. Barely anyone talks about student sexual health these days – despite the fact that gonorrhoea diagnoses are at a record level, and the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) think’s that’s students. Its annual half-arsed press release isn’t going to cut it.

Drugs policy needs a look beyond a PDF that UUK hoped the Telegraph wouldn’t notice by slipping it out during the election. There’s something important going on with students and disordered eating that everyone seems determined to ignore. They’re not getting nearly enough sleep. At this year’s Secret Life of Students we heard about the dental issues that students increasingly present with. And so on.

The debate about student health right across the UK tends to be stuck in a sort of accountability void – that students get poor access to both preventative healthcare and health services is either justified on a pressured NHS dealing with an ageing population, or universities being expected to do more with less.

Both are true – but it leaves the crucial link between health and study success stuck in that Spiderman meme, while the public just read the Mail and blame students for boozing it up and inventing ADHD.

It also settles on a statist NHS versus increasingly complex and diverse universities – when it may well be the case that structures at a local or regional level that are distinct from both, that pool resource, engage students as partners and focus on them specifically, would be a better bet.

As ever, departmental siio-ing and the knights and knaves in charge demanding more money for them and their service are the ever present threats to taking students seriously anywhere. But health is a precursor to education. That’s two of the 5 missions right there.

Either way, at this end of the Parliament I’m minded to take Wes at face value. I’ll be arguing that no plan for the NHS that involves pushing services out from hospitals into communities will work without a proper plan for and with students – and I’d encourage you to do so too.

The SU bar in our local County hospital was a pale shadow of it’s former self before being closed and used for other space hungry things, I spent many a night enjoying the company of student nurses there, and ran the bar for special events in the SU bar in the district hospital, again long since closed. Student nurses now buy cheap alcohol and often drink in isolation, using alcohol as a crutch when the pressure of poor University academic Nurse instructors combined with money worries gets too much. It’s a bigger health issue than the old bar culture group… Read more »