In some ways, it makes no sense.

Scotland is apparently so hard up that Graeme Dey, its further and higher education minister, says he can’t rule out further cuts to university budgets:

We are not really going to know the scale of the challenges until we see the UK budget, but I think it is pretty clear that we are not going to suddenly emerge from some difficult and challenging times we have had, into something better. So that is obviously a concern.

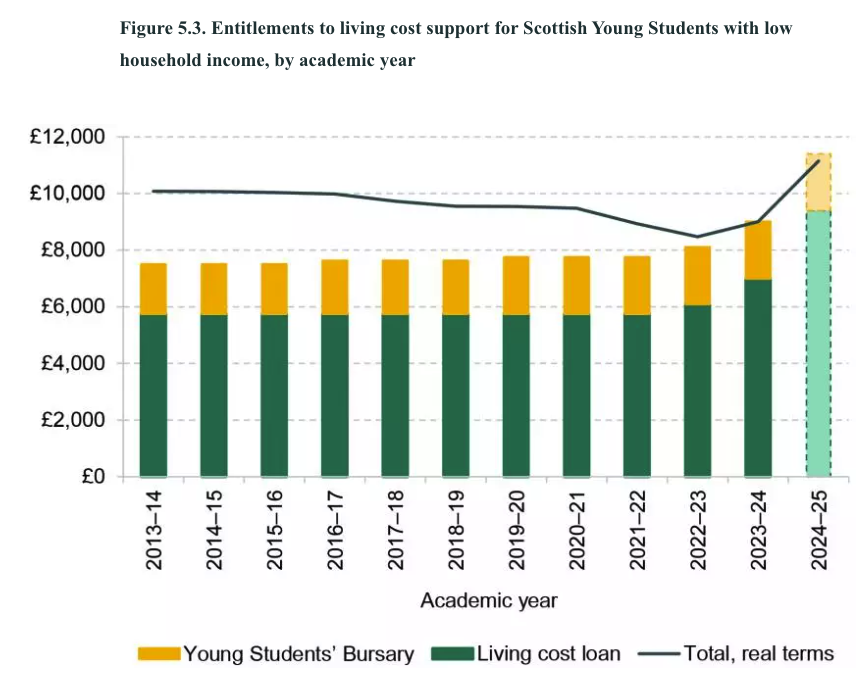

But he says that in the same month that Scottish students will start to see a £2,400 increase on the maintenance package via the new “special support loan” – which postgraduates are getting too.

And that comes merely months after the loan repayment threshold (above which graduates make repayments on their loans) increased from £27,660 to £31,395 in April 2024 – reducing monthly repayments for almost all graduates.

Given it’s a loan not a grant, the easiest way to read the contradiction is to figure that because Scotland is becoming more and comfortable with maintenance debt, it’s happy to have that balloon while holding down the tuition end of funding.

It’s a comparison that’s missing from the otherwise excellent paper from James Miller (Principal at the University of the West of Scotland) that appeared earlier this month on the cost of “free” higher education.

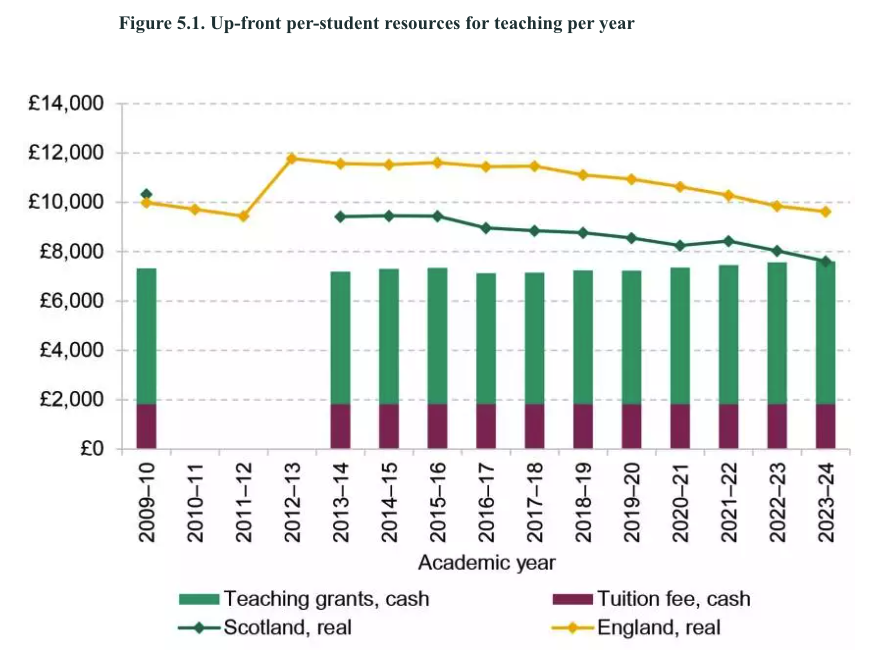

It quotes a London Economics paper that suggests that higher education institutions in Scotland receive approximately 23 per cent less funding per student than their counterparts in England – which does raise the uncomfortable question of how any university in Scotland is surviving given the apparent funding crisis in England. Here’s the IFS version of those figures:

But as I say, it doesn’t mention the maintenance at all. And as a result, it’s silent on the way in which the Scottish system cuts its subsidy nose off to spite its funding face.

Hey big spender

In the year just gone, IFS calculates that around £1.5 billion was spent on undergraduate HE in Scotland – including teaching and living cost support. But only about £1bn comes from Scotland’s budget in the form of tuition fees paid on behalf of Scottish students, grants to universities through the Scottish Funding Council and bursaries.

Maintenance loans – and any subsidy attached to them via the write off and repayment threshold – are managed and financed by the Westminster Treasury in what’s called an Annually Managed Expenditure (AME) programme.

The arrangement – which applies in Wales and Northern Ireland too – depends on the Scottish Government’s higher education funding policy having “broadly comparable” costs to the policy in England. And it turns out that that’s not determined by the cost per student, but by the cost per head of population.

So this isn’t just about trading tuition funding off for maintenance. It’s also about trading Scottish budget funding off for Westminster budget funding.

Depressing the participation rate ends up being advantageous for maintenance – because the Scottish Government can look generous by claiming more of the free subsidy on maintenance loans from Westminster.

That’s not to say that there’s no cost to the Scottish government when it puts up maintenance debt – but it’s a political cost associated with the optics of “plunging students into debt”, rather than a cost that ministers have to jockey over in budgets.

As such, it’s worth considering what could happen next.

Manifesto commitments

The £2,400 bump on maintenance was an SNP manifesto commitment – to deliver on the 2017 Student financial support review recommendation to take the total package to a level equivalent to the Scottish Government’s Living Wage.

That’s the Real Living Wage, calculated as follows:

Anchor

- Scottish Government’s Living Wage: £12 per hour

- Notional hours of study per week: 25 hours

- Weeks per academic session: 38 weeks

- £12 x 25 hours x 38 weeks = £11,400

Total: £11,400

Entitlement

- Scotland UG Max Loan: £9,400

- Scotland UG Max Bursary: £2,000

Total: £11,400

On the assumption that the Resolution Foundation announces an increase to the Living Wage in a few weeks time, that’ll push up the notional max entitlement. The RAB charge (ie subsidy) on Scottish student loans is not published – but it’s a fair bet that the allowed subsidy total hasn’t reached its allowed ceiling yet.

All that Scottish ministers will have to do is trade off the political gains of hitting their manifesto commitment with the political hit of students getting into more (maintenance) debt.

So it’s likely that the real ceiling on sustaining the system in this way isn’t ever more generous maintenance – it’s universities in Scotland getting so little per-student that campuses close (Miller’s UWS maintains expensive-looking facilities in Ayr, Dumfries and Lanarkshire as well as the big base in Paisley), courses thin-out intolerably or even institutions collapse.

The totemic “free education” pledge is already under strain – add up the maintenance debt that undergraduates are in, then add in the hugely less generous support that over-25s get, and sprinkle in the vast numbers of postgraduates whose tuition fee of up to £7,000 goes nowhere near covering their fees (with nothing on offer for PGRs) and it starts to look much more like a political symbol than a lived reality.

Who pays what

The debt and lifetime repayments suggest that the gulf is much narrower than it looks. If you’re a young student whose family earns £45,000, you’ll likely borrow £33,600 in maintenance loans over a four year degree (not accounting for entitlement increases over the four years) – and on average, you’ll repay almost all of that within your lifetime, because you’ve got a lower debt to clear than friends in England.

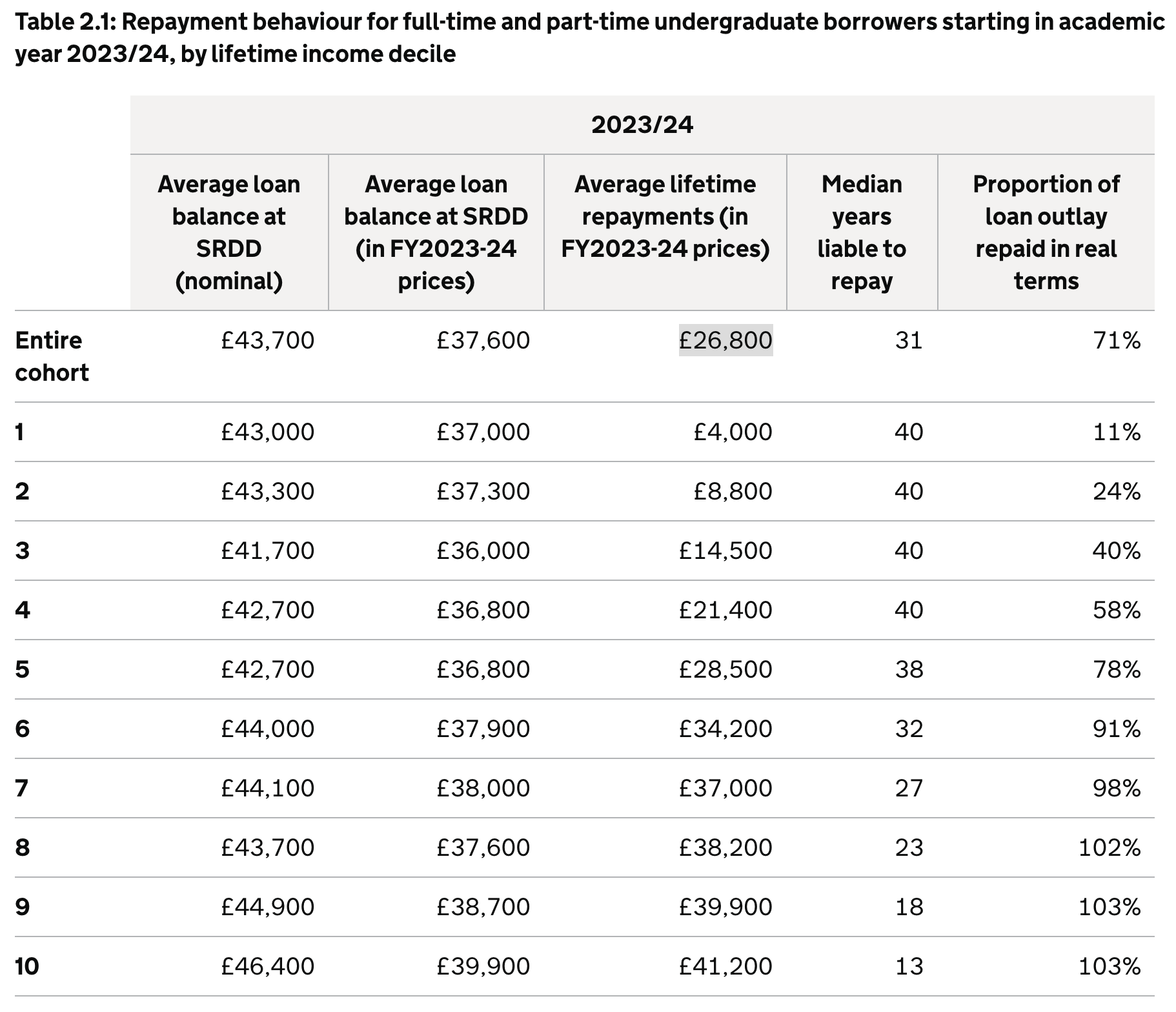

South of the border, a student whose family earns £45,000 and who is living at home will likely borrow £23,661 in maintenance (again, not accounting for entitlement increases over the three years) and £27,750 in fee loans – £44,818. But DfE’s own figures suggest that you’ll only end up repaying £26,800 of that. So who’s getting the better bargain?

Naturally, when you have a policy as symbolically salient as “Free Education”, explaining the complexity of the RAB charge to voters is not an option – especially as the SNP’s time in power slowly reduced the list of achievements it is able to rattle off.

But that then raises questions for Scottish Labour and what it might do to ease the situation.

When fees and funding gets debated, we’re often pointed to examples from around Europe. Germany is free, Ireland is free, Serbia is free, and so on.

But in Ireland, the annual “student contribution”, formerly called the student services charge, covers student services and examinations – its maximum rate in 2023/24 was €3,000 a year.

In Serbia, fees are means tested – and the 4 in 10 of those who don’t pay tuition fees pay administrative, entrance and application fees, and fees for issuing diplomas and diploma supplements – as well as fees for changing an examiner, switching study program , changing elective subjects and getting recognition for exams taken at another higher education institution.

Even in Germany there’s extras to pay. At the University of Stuttgart, for example, students pay €70 in administrative fees, a €96.50 student services fee, and a €7.50 SU fee, all per semester – €348 a year in total.

In other words, while the simplistic totem of fees for “tuition” is held down or free around the EU, a tiny minority of countries offer everything that the definition of “tuition” covers in Scotland.

A non-tuition fee

So let’s say that, for example, Scotland was to levy a £500 student services charge per-undergraduate that students could all borrow on top of their maintenance loan.

Let’s give £100 of that to funding the students’ association – helping to build belonging and democratic participation amongst students and strengthening the student voice in the process. You could even continue to allow opt-out for those who want to reduce their notional debt levels.

Let’s then take £400 of that and allocate it towards student services – to include everything from counselling to catering – but let’s put a distinct type of governance around it that gives students much more of a statutory say over how it’s spent in the form of a Student Services Council. That’s what they do in Belgium – and the sky hasn’t fallen in.

At Miller’s institution in Paisley alone, last year £29m was spent on academic departments. This student support fee would raise just shy of an extra £6m from undergraduates to improve services and support for students, allowing some diversion of existing spend in that area to those academic departments – all while keeping tuition free.

For the undergraduate on four year programme whose family earns £45,000, the debt level would rise from £33,600 to £35,600 – and to the extent to which some will pay that off and some won’t, it’s only the most successful graduates that would pay it – with those whose remaining debt is wiped at 30 years getting that student services fee paid for by unspent subsidy from Westminster.

Retaining the totem of free tuition is one thing. Cutting off your tuition fees nose to spite your student services subsidy face is quite another. Scotland should restrict its definition of “free tuition” to just that – and make Westminster pay the poorest’s contribution from its unspent loans subsidy pot.