If you walk around Oxford (or Cambridge, to be fair) you can get a sense of timelessness, of ancient cloisters, of traditions spanning the centuries. And some of this is true. But not everything that was started in these cities has lasted, as we shall see.

Regular readers might recall that it is not just colleges which Oxford had, but halls too – (it’s in this post on St Edmund Hall). These were run as little businesses: by providing rooms and a principal to oversee them, the owner could charge students rent. It’s a much earlier version of the business model of student housing providers we see today.

In 1282, or thereabouts, Hart Hall was established by Elias de Hertford. In 1301 Elias transfers ownership to his son, also Elias, who promptly sells the business to John of Ducklington. Ducklington adds the neighbouring Arthur Hall to Hart Hall. There were more transactions, culminating, in the mid 1310s, to the sale of the enlarged hall to the Bishop of Exeter, Walter Stapledon. This, to be clear, has consequences.

The bishop was looking to establish a college, but after a year a better site in Oxford became available, and he purchased land on Turl Street to found Stapledon Hall, which became Exeter College a year later in 1314. Hart Hall at this point operated as an enterprise which subsidised the running costs of Exeter College.

(Stapledon, by the way, came to a bad end. He was involved in high politics, twice serving as treasurer to King Edward II. These were difficult times for the country, with civil war, invasions and the like. Stapledon picked the wrong side, and did the wrong thing. In October 1326 he was spotted by an angry mob in London, and captured. Two of his aides were beheaded; Stapledon suffered a nastier death, as set out here.)

In 1370 we had the same story, but with a different bishop and a different college. William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester, was seeking to establish a college, and leased Hart Hall as accommodation. When New College was completed, his scholars moved there, with Hart Hall serving simply as additional accommodation.

But it seems that Hart Hall still had a principal, so it was not simply a set of buildings. The college’s history tells us that through the 1400s and 1500s it expanded with more buildings, some bought (Black Hall and Cat Hall) and some built, the latter still part of the college today. Hart Hall was showing signs of autonomy! It also began to accumulate its famous alumni, starting with John Donne, my favourite metaphysical poet, who studied at Hart Hall in 1583.

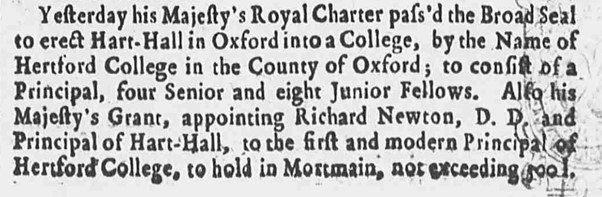

In 1740 Hart Hall was transmogrified. The Newcastle Courant of September 20, 1740 reported that:

This status was not won easily: Dr Newton campaigned hard, and against the wishes of Exeter College which, you will recall, had a claim on the freehold via the Bishop of Exeter. The college was named for the original founder of Hart Hall, Elias Hertford.

But the new college did not have enough money, and in 1805 it closed, when nobody could be found to take on the principalship. But – as is so often the case – the site may change hands, but the underlying use continues. In 1816 parliament passed an act so that Magdalen Hall – another private hall, this time associated with Magdalen College – could take over the site, the site itself being bought by Magdalen College.

There was building and rebuilding, but Magdalen Hall still struggled until, in 1874, Thomas Baring, banker and MP, gave £30,000 (£2.85m in today’s money) to re-found the hall as Hertford College. (Baring subsequently gave much more money to the College: he had hoped to give it to Brasenose College but that college did not accept his stipulation that the money be used only to support members of the Church of England.)

Now that it was properly endowed, the college went from strength to strength. More new buildings followed, to enable it to grow. And in 1913 the iconic Bridge of Sighs was built, connecting the college with the new buildings across New College Lane.

Here’s a bonus postcard, showing the Bridge of Sighs.

A wonderful apocryphal tale exists, that on one occasion a survey was taken of Oxford students’ weights. Hertford students were, so the tale goes, found to be the heaviest and so the college closed off the bridge, requiring them to walk down and cross the road.

Sadly, there are two fundamental problems with this tale. Firstly, it actually requires fewer steps to cross between the buildings without using the bridge than it does when the bridge is used.

And secondly it didn’t happen.

Also notable is that the bridge looks more like the Venetian Rialto bridge than the Bridge of Sighs. As the comparison below shows.

But enough of bridges.

Hertford slowly established itself through the twentieth century. Evelyn Waugh was a Hertford student (“I do no work here and never go to chapel”), and Charles Ryder, the narrator of his Brideshead Revisited, was a Hertford student too.

Later in that century Hertford did something very radical (for Oxford). Neil Tanner became admissions tutor, and in the late 1960s pioneered a scheme whereby applicants from state schools were encouraged to apply, and were given a different admissions route, often bypassing the then ubiquitous entrance exam. Two wonderful things happened: firstly, Hertford gained a more diverse (in terms of class and educational background) student body; and secondly it went from the bottom to the top of the Norrington Table, the annual comparison of Oxford colleges’ performance.

More radical changes occurred in 1974, when Hertford was amongst the first of the all-male colleges to admit women.

Hertford’s alumni (and those of its predecessor institutions) include some very famous names: we’ve noted John Donne and Evelyn Waugh, but we can also add Jonathan Swift, Thomas Hobbes, and William Tyndale, amongst many other big names. And more recently, and very notably for policy wonks in HE, Bridget Phillipson, Secretary of State for Education, and Jacqui Smith, Minister for Skills, Apprenticeships and Higher Education, are both Hertford alumni.

The card at the top of the blog was posted on 29 November 1925 to Miss Stephens, in Plymouth. “With love to and best wishes to all, E”.

The bonus Bridge of Sighs card was sent undated (but with King George VI stamps) to Miss Benson, in Peebles:

Tell your mum that I’ll be back in Peebles on Sunday morning and will see you, all being well, next day, Monday. JH