A recurring theme we have heard throughout our discussions about academic support this year is that it is very hard to know “what works.” By this statement, people generally mean that it is almost impossible to trace a particular activity or intervention with a student to that student’s overall success at staying on their course, or achieving academically.

That is because academic support has the features of a complex system: it has diverse interacting components (academic staff, professional staff, students, data systems, meetings, emails, websites); its different components interact with each other in unpredictable ways; and most of those components learn and adapt their behaviours because they are human components.

It is also because academic support provision is inevitably only one factor in student behaviour and decision-making; students who are successful may have benefitted from a supportive family or a close-knit peer group, or may just be that tenacious to succeed in spite of not having any of those things. And it is rare for a university to only be in the process of changing one thing at a time in ways that could cause the impacts of that thing to be tracked in isolation from other possible complicating factors.

This doesn’t mean that academic support cannot be evaluated. It is possible to isolate features of the system and test them. One example of a well-designed evaluation in academic support is a recent evaluation by TASO to test the efficacy of support interventions for students who had been flagged on a learning engagement analytics system as being at risk of early exit due to their engagement profile. The evaluation sought to determine whether it made a difference if the students flagged as being at risk received an email, or an email and a follow-up call. Overall the evaluation found no significant difference between the two groups in whether students re-engaged. But it did find that the students who took the call (and reported back on their experience) appreciated the personal connection.

It is fairly straightforward to capture sentiment from staff and students about what they think about the system, and their perceptions of whether it is effective – and doing so in a systematic way will surface all kinds of detailed insight. It is also possible, where engagement data analytics systems are in use, to analyse data patterns of individual student engagement and cohorts over time, tracking the ebbs and flows. The availability of data is not in itself a problem, but it is quite difficult to draw meaningful links between data, activity, and outcome. That is where systems thinking comes in.

Systems thinking

Up to this point we’ve referred to academic support as a “system” in the sense that it has lots of interlocking elements, but the reality may be that different parts of academic support systems have sprung up at different times and to serve different constituencies. What one university considers to be part of its academic support system may be entirely different from another, and different staff teams and student groups may also have their own views. Any effort to change or enhance one aspect of academic support may then have knock-on impacts in other areas but without having a whole-system view this might not be anticipated or even noticed.

Our working assumption is that in most institutions, given the changing patterns of student engagement and complexities of students’ needs, “academic support” is no longer a way of describing a personal tutoring system that acts as an all-purpose backstop point of contact for students wanting advice and support. Instead, it is increasingly imagined as a core element of the academic provision of the university; wrapping around the curriculum to support and guide students on a development journey towards academic success and the acquisition of graduate attributes. That shift requires a deeper dive into the elements of the system and how the different elements interact with each other.

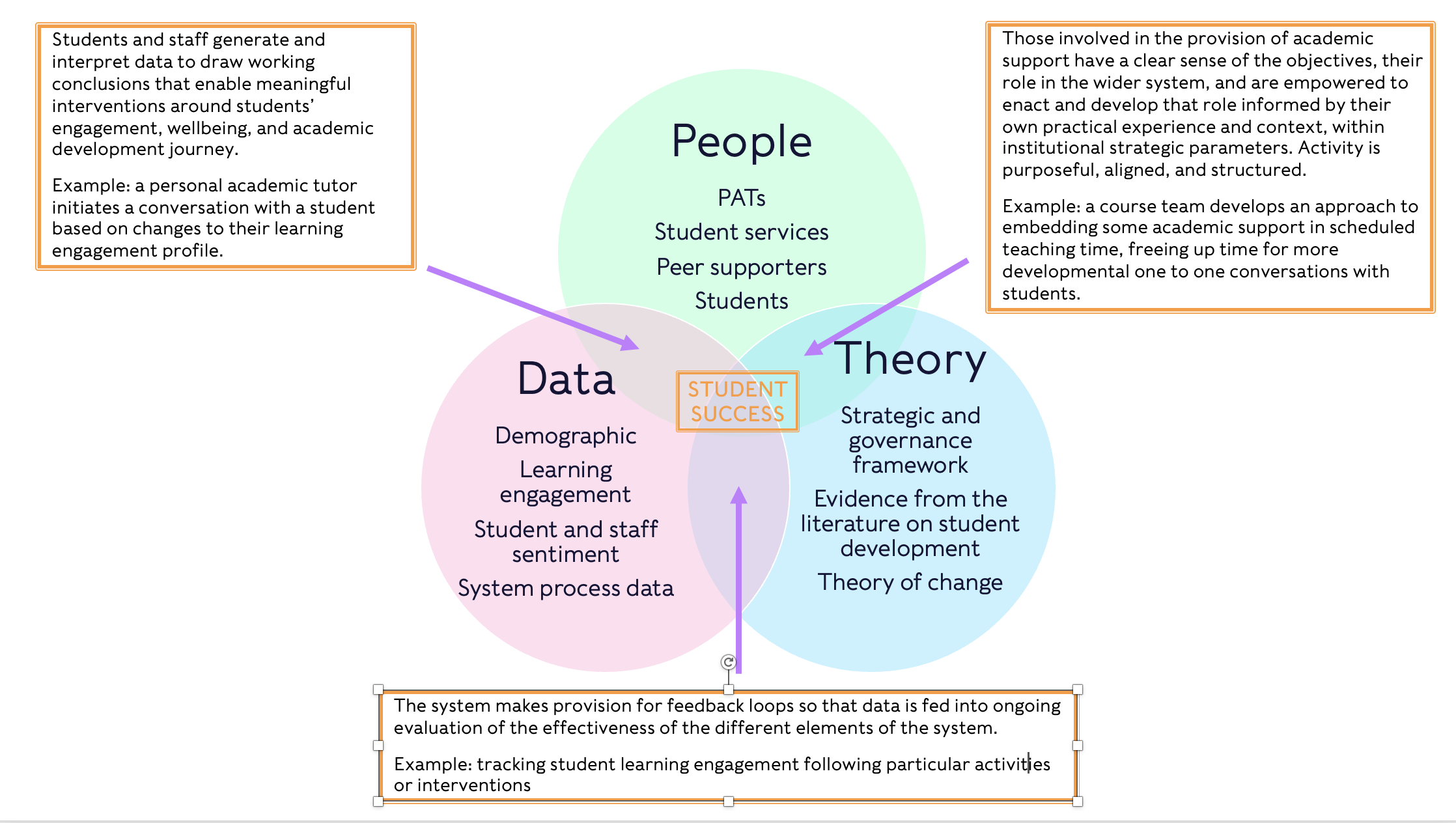

You can view and download a larger version of the academic support system model here.

Whatever the distinctive elements of any given academic support system, our sense is that it will involve three core components: people, data, and “theory” illustrated in the above diagram. Without any one of these elements the system, like a wonky stool, will fall over.

“People” is obvious: it’s personal academic tutors/personal development advisors or the institutional equivalent, professional services; student peer supporters and students themselves. “Data” is also reasonably well-understood: it’s all the available insight about students and the system itself, which could include things like data from pre-arrival questionnaires; student evaluation surveys; learning engagement analytics data; data on student interactions with various parts of the institution; data about student demographics and so on, that inform the actors in the system about what is going on with students and guide their actions. What people and which data any given institution considers to be part of its academic support system will vary, but in deciding what should be included and what excluded, the system needs theory.

“Theory” is a much less well-established aspect of an effective system, but it’s vital to being able to describe it, evaluate it, and enhance it. Acknowledging the role of theory means recognising that people act according to their (often very well informed) perception of what is appropriate and effective in particular contexts. What may be driving an academic support system is multiple competing tacit theories of academic support and student development held by the different actors in the system. Surfacing some of these assumptions, in a systematic rather than anecdotal way, can bring to light a great deal of practical expertise and knowledge gained through experience, as well as some “lived experience” insight that may explain why some elements of the system aren’t working as well as they should.

To be able to design an academic support system in the first place – but certainly to evaluate its elements and overall impact – there needs to be a grounding theory that explains both the overall objective of the system in terms of the sort of development journey it is intended to take students on, and how the different elements of it act together to achieve those objectives. This latter element is what evaluation experts call “theory of change” – and it is surprising how frequently whole suites of activities are designed and launched without an articulated theory of change that describes not just what the intended impact is, but why these activities are the most plausible ones to achieve it.

“Theory” makes it sound like it needs to be deeply academic, and certainly we would expect in a university context to see an active body of thinking and evidence drawing on the literature of student engagement and development. But it can also mean the policy and strategic framework governing academic support that offers a shared language and commonality of overall objectives for the actors in the system to draw on when making autonomous decisions about how to act. The theory would typically be “held” within a governance structure – an academic support steering group for example – that has oversight of the design of the system, and authority and responsibility for making decisions to evaluate and enhance it.

In our model, the system as a whole is built around the effective interaction of people, data, and theory. The student is “at the centre” in the sense that all the elements of the system are geared towards their success. The entire system is evidence/data-informed to help make best use of existing resource across the entire student support provision – at individual, course and cohort, and whole-institution levels. The model can’t tell you what the different elements of an academic support system should be, but it can prompt some thinking about how these different elements are expected to interact.

As one of the participants in our group of partner universities commented when we discussed evaluation, one of the first things you need to do even before evaluating your system, or any bit of it, is evaluate whether you have a system – in other words whether all the aspects of the system you have designed are working as they should.

For example, are data systems feeding insight to personal academic tutors in the way it was designed to? Are personal academic tutors drawing on student learning engagement analytics data in their meetings with students? Are central services responding to student requests for support within the timeframe they are supposed to? Can people generally describe the system and its objectives and do they feel able to execute their responsibilities within it? If anything is not happening, why not? Were there assumptions made during the system design that turned out to be too optimistic and need to be reviewed?

Once you have confirmed you have a system, you can start to use evaluation methodologies to probe its weak points, areas for development, and opportunities for improvement. Rather than looking at whether one aspect of the system is (for example) contributing to student retention, it’s a bit more feasible to build a theory that (for example) tests which activities to support transition into university are most strongly correlated with the likelihood that students will demonstrate learning engagement behaviours at an early stage in their course, which we already know has a fairly consistent link to student outcomes.

It is much more effective to test the links between elements of a well-theorised system than it is to try to support a claim that (for example) a meeting with a personal academic tutor in the first four weeks of the course has a direct correlation with academic performance at the other end when it will be a multitude of interacting elements that contribute to that final outcome. Evaluation experts describe this as a “contribution model” as opposed to an “absolutist impact model” and it leaves much more space available to accommodate complexity and difference. Another approach can be to ask actors in a programme or activity to share their analysis of what the most significant change has been for them – this is insight that can inform the evolution of the theory of change, as it might not be the same thing that was intended by the activity in the first place.

Practical wisdom on evaluation

The reality, as evaluation experts will tell you, is that it is rare for a complex system to be designed in its entirety from scratch, with a well-articulated theory of change driving decisions, and all its assumptions thoroughly tested. It is much more likely that someone has a good idea, wins a level of senior support and backing to test it, and then needs to evidence the value to be allowed to keep on doing it.

When people think about evaluating there can be a sense of almost a moral imperative to adhere to the highest academic standards, and evaluate every aspect of the impact of a programme or system, which can leave some paralysed by the scale and complexity (and expense) of the task. Often it is appropriate to bring in experts to carry out large-scale evaluation of multi-year projects – especially if you invite them in to help with the design thinking rather than asking them to evaluate a project whose objectives and theory of change were never especially well defined (though evaluation experts will also tell you they are fairly stoical about that). Those wanting to further investigate large-scale evaluation of complex projects may find this complexity evaluation toolkit from the The Centre for the Evaluation of Complexity Across the Nexus (CECAN) helpful.

But in times of shrinking resource and tight finances the sector as a whole has to develop and adopt a pragmatic evaluation practice that works for day-to-day business, to be assured that things are working, fix them if they are not, and guide decisions about where to put resources where they can have the greatest impact. In particular, being pragmatic about the purpose of the evaluation, who its stakeholders are and what they want or need to know, is a helpful way of narrowing focus to something that is achievable within whatever constraints are in operation.

For example, when stakeholders are participants in an expert community of practice, rather than testing whether something “works” at a high level, they might really want to know why, when, how, and for whom it works so that the learning can be shared and that good practice spread in ways that are appropriate to different contexts, or check whether there are groups who have been inadvertently excluded who might need a different approach. Other evaluation stakeholders will have different priorities and needs – and these can most easily be understood by asking them.

But where something complex like academic support is concerned, especially where there is considerable space for academic and student autonomy in interpreting and enacting the system, and a plethora of external factors that are shaping the intended outcomes that are outside a university’s control, it is best to think in terms of using evaluation to better understand and enhance the system, without a fixed end point in mind. There is no perfect “best practice” version of academic support, no optimal use of data, no sector-leading model of personal academic tutoring. There is only the incremental accumulation of knowledge about any given institutional system, to guide decisions about the development of that system. Looking at what other institutions do may spark ideas, but it won’t offer a blueprint.

Focusing institutional capability on building informed theories about how elements of the system work, testing and developing them in partnership with the system’s various stakeholders, and embracing “double loop learning” to challenge and enhance the collective mental models that underpin the system will deliver a system that might not be perfect, but it will be one that is capable of continually adapting to the changing context of students’ needs.

The evaluation insight in this article was contributed by Julian Crockford, senior lecturer in student experience evaluation and research at Sheffield Hallam University, who kindly acted as advisor to this element of the academic support project.

This article is published in association with StREAM by Solutionpath and Kortext. You can access Support to Success, the full report of our year long project on academic support here.