National service isn’t a thing. Or is it?

Jim is an Associate Editor (SUs) at Wonkhe

Tags

When former Aylesbury MP Sir David Lidington was pushing the policy back at the beginning of April, one of the incentives was that you “could knock a bit off their student loan debt” if students were to be dragged in.

No sign of that this morning.

We’ll introduce a bold new model of National Service.

To up-skill the next generation, make our nation secure & build a stronger national culture.

Whether in the Armed Forces or volunteering in our NHS, every young person will do their duty to build a secure future for the UK. pic.twitter.com/qgLTv022RN

— Conservatives (@Conservatives) May 26, 2024

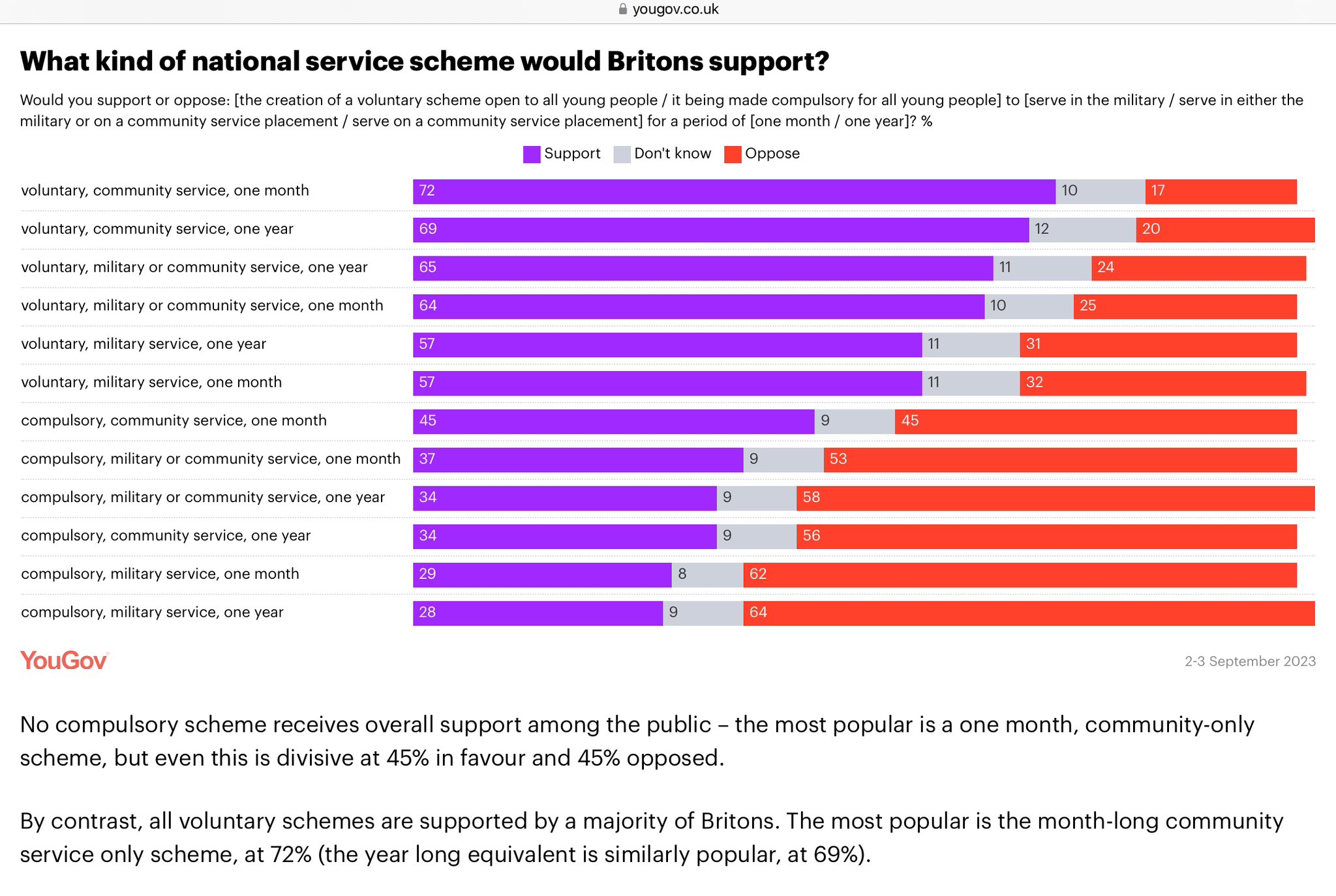

While the Conservatives’ news cycle agenda-setting announcement of a “bold new model of National Service” to “up-skill the next generation, make our nation secure and build a stronger national culture” might sound like an idea for a programme on Alan Partridge’s dictaphone, it actually polls surprisingly well:

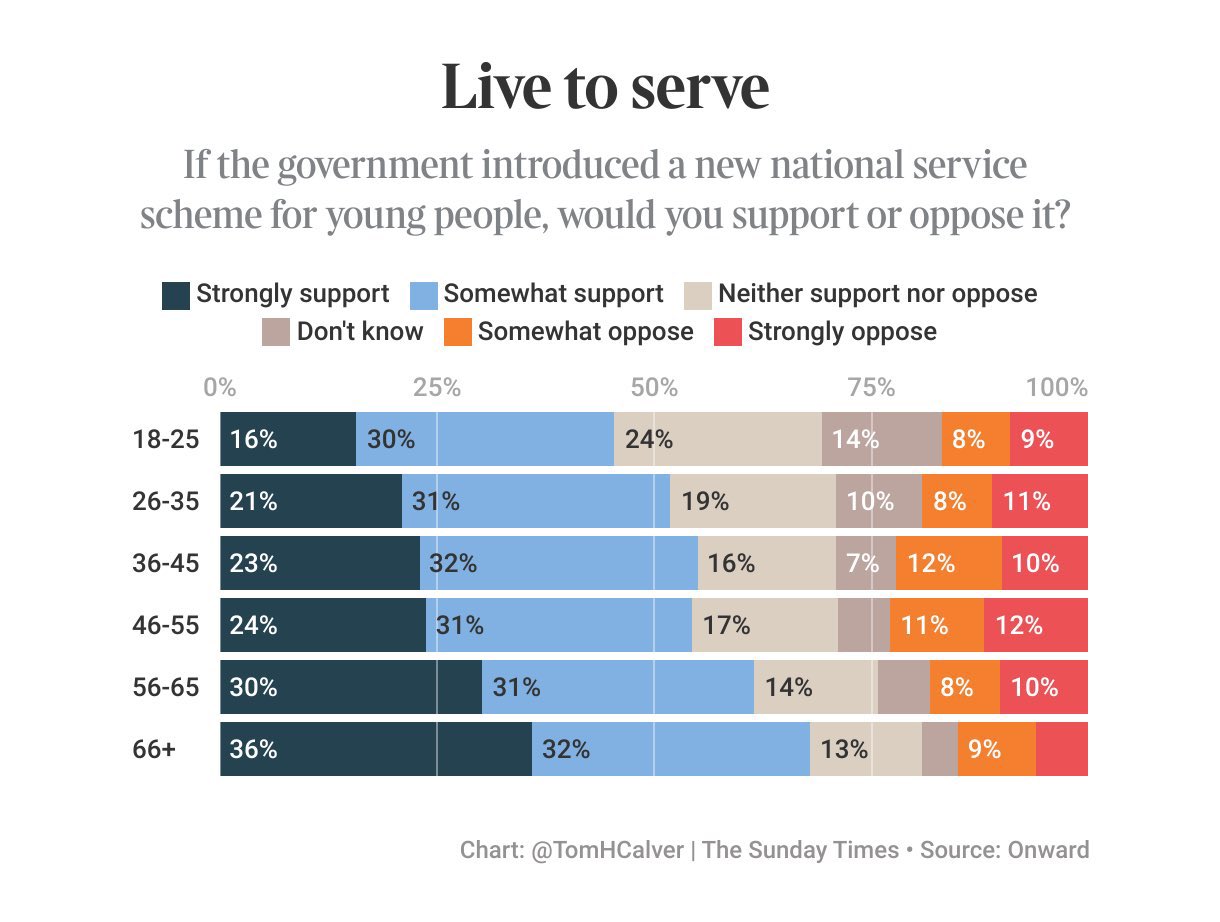

Nevertheless, there are major differences by age – and in the age-bifurcated politics of our time, the contrast between the signal that one partly wants to listen to the young (Votes at 16) and another thinks that they need to be told couldn’t be more vivid.

As for the policy itself, it’s actually been being worked up for some time – it’s a version of this paper from influential centre-right think tank Onward that was published last August.

Delighted that a new flexible form of national service will be in the Conservative manifesto, as @ukonward has called for.

Last year, @ahawksbee and @Valen10Francois examined what has worked what a new opt-out Great British National Service could look like 🧵

— Sebastian Payne (@SebastianEPayne) May 26, 2024

The “detail” runs something like this. 18-year olds will be given the choice between a one year, full-time course or spending one weekend a month volunteering in their community.

Up to 30,000 positions will be created either in the armed forces or in cybersecurity training for the former option, and the weekend placements could be with the fire or police service, the NHS, or charities “tackling loneliness and supporting older, isolated people”.

Not, you’ll note, charities tackling loneliness and supporting younger isolated people.

There’s a pledge to set up a royal commission to design the £2.5 billion programme, and should the Conservatives win the election, the pilot will start next year – then by the end of the next parliament, legislation will be passed making it mandatory for all 18-year-olds. Sunak:

This new, mandatory National Service will provide life-changing opportunities for our young people, offering them the chance to learn real world skills, do new things and contribute to their community and our country.

It’s hard not to draw comparisons. On IFS figures, that £2.5bn is roughly the same long-run amount that the government chips in towards tuition fees and maintenance loans for a whole cohort of HE students.

The “plan” is to fund it partly by cracking down on tax-dodgers, and partly by repurposing the existing levelling-focussed UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) – which currently funds projects around the country focussed on communities and place, support for local businesses and people and skills.

It funds stuff like DurhamWorks – which aims to find jobs for young people in County Durham and to remove any barriers preventing young people from progressing into employment – and helps with the costs of childcare, clothing or transport costs, as well as providing funding for employers to create employment opportunities for young people.

It’s not immediately clear that it’s necessary to test the implications this far – but of course if the intention is to impose it on 18-year olds, that does mean that the UK’s conveyor-belt into higher education would be disrupted.

It doesn’t help that we have some of the youngest undergraduates and therefore youngest graduates in the OECD facilitated via our assumption that universities are big (boarding) schools, but the plan would appear to mean delaying going into higher education or taking up students’ weekends.

The sector would want to know where the money is coming from to cover the enrolment gap that the former would represent, and as for the latter, students are already volunteering (just not necessarily in the types of roles that this would fund), or they can’t because they can’t afford to.

Much has been made of Northern and Eastern European comparisons by some – in Denmark, for example, national service lasts between 4 and 12 months – but it is possible to postpone it until education is complete, and women will shortly be included.

The Baltics have been debating it too – just last week Lithuania cancelled deferment for university students and will draft them immediately after school, despite its Committee on Education previously proposing not to interfere with the learning process of current students, and to draft young people after school with only a few exceptions – postponing service for very bright students, athletes, and artists.

It sounds fantastical and farcical to contemplate that actual military conscription might return to the UK any time soon. But it’s very much a reality in plenty of countries that are closer to Russia, ones that many would regard as more social democratic or left-wing in character.

It almost certainly won’t be a thing in the next Parliament. But if the past few years have told us anything, a more volatile and uncertain world might make it one.