Non-continuation is an important issue for many this autumn.

With a review of the National Student Survey underway and a recession harming graduate outcomes, non-continuation is posited as an important metric by which to judge course value being consistently advocated by the Westminster government. There are major potential financial implications of non-continuation for universities and the wider sector. And of course, there are significant human, financial and opportunity costs for an individual student that drops out.

Following several discussions with students’ unions, we wanted to develop a short, sharp national survey on the issue – which we ran in collaboration with Trendence UK and 30 students’ unions throughout October. We wanted to know whether students are considering dropping out, who is most at risk, the reasons why they’re thinking about it and what they think universities and students’ unions could do to help.

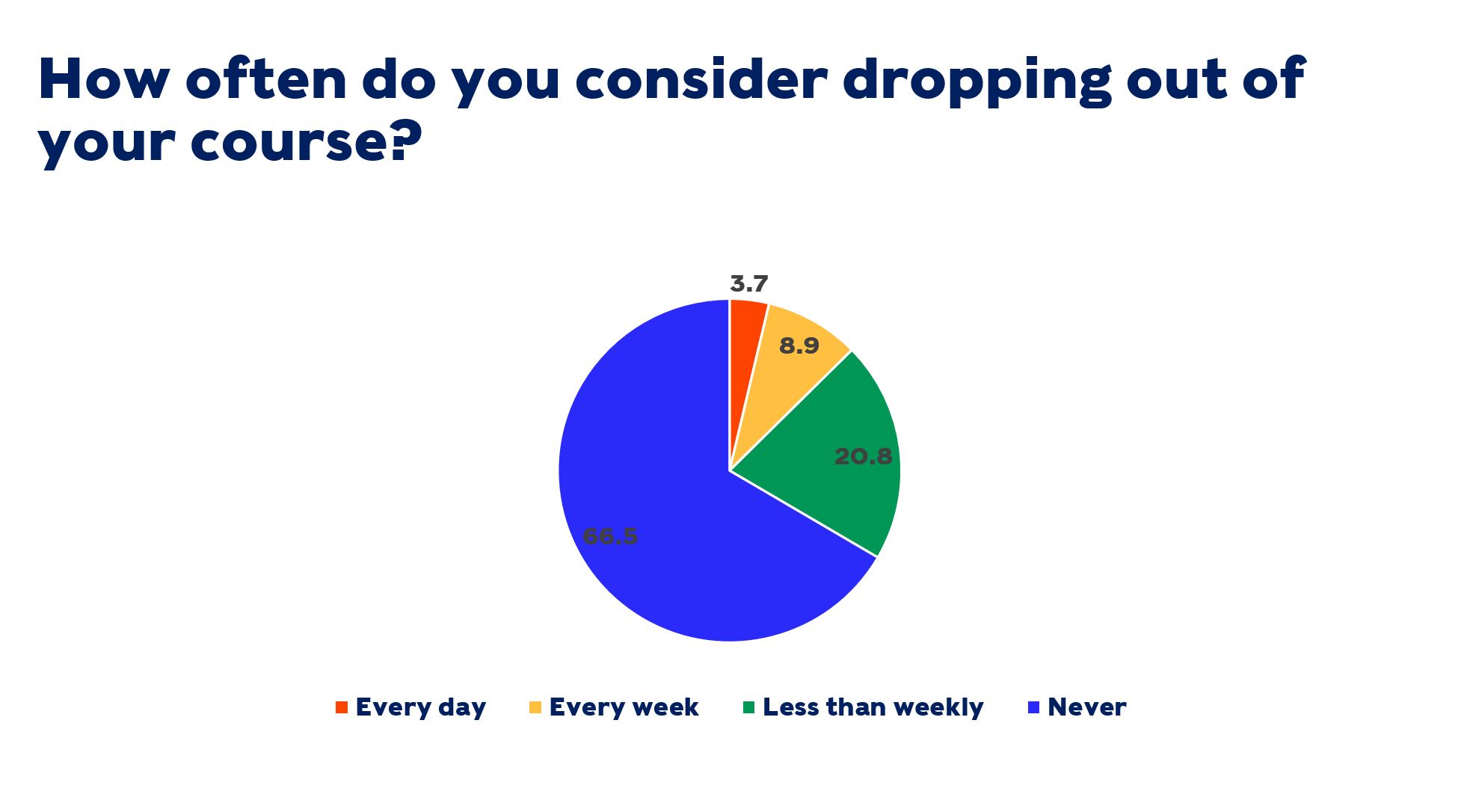

Over 7,000 students took part from 121 institutions. The results do reveal that a significant proportion are considering dropping out – 12.6 per cent, rising to roughly one in five students from non-selective state schools and disabled students.

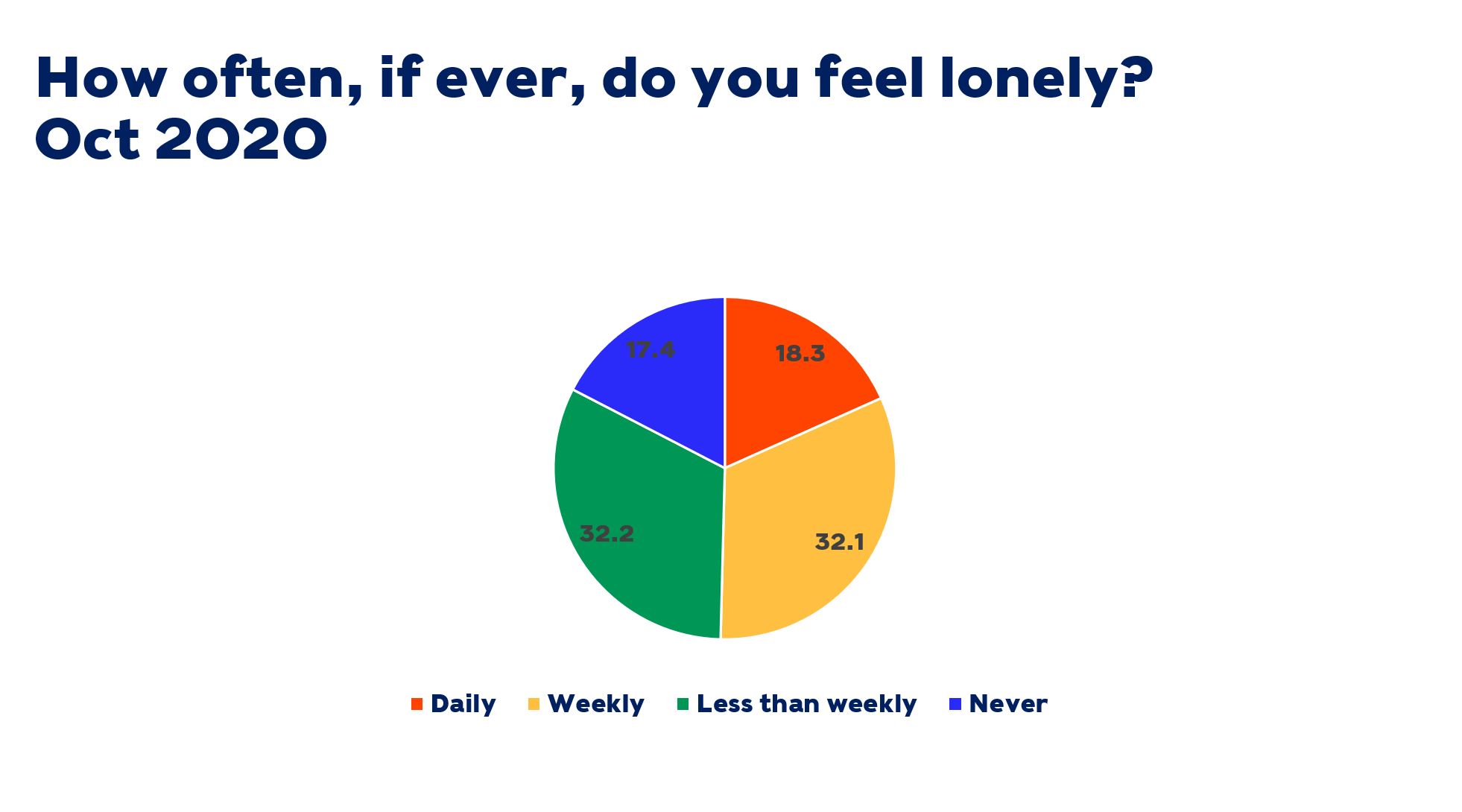

But perhaps more important are the findings on wellbeing and mental health. Over half of our sample report feeling lonely on a daily or weekly basis. Just 8.2 per cent report strong feelings of happiness, down from 14% before the pandemic and 32 per cent for young people pre-pandemic. And it is feeling part of a community and loneliness that are both strongly related to considering dropping out.

Today we’re focusing in on mental health, loneliness and non-continuation – and we’ll consider other aspects of the findings later.

Non continuation and loneliness

To follow up on our last piece of work on student loneliness in May 2019, we first wanted to know how lonely students were feeling – and there has been a concerning increase:

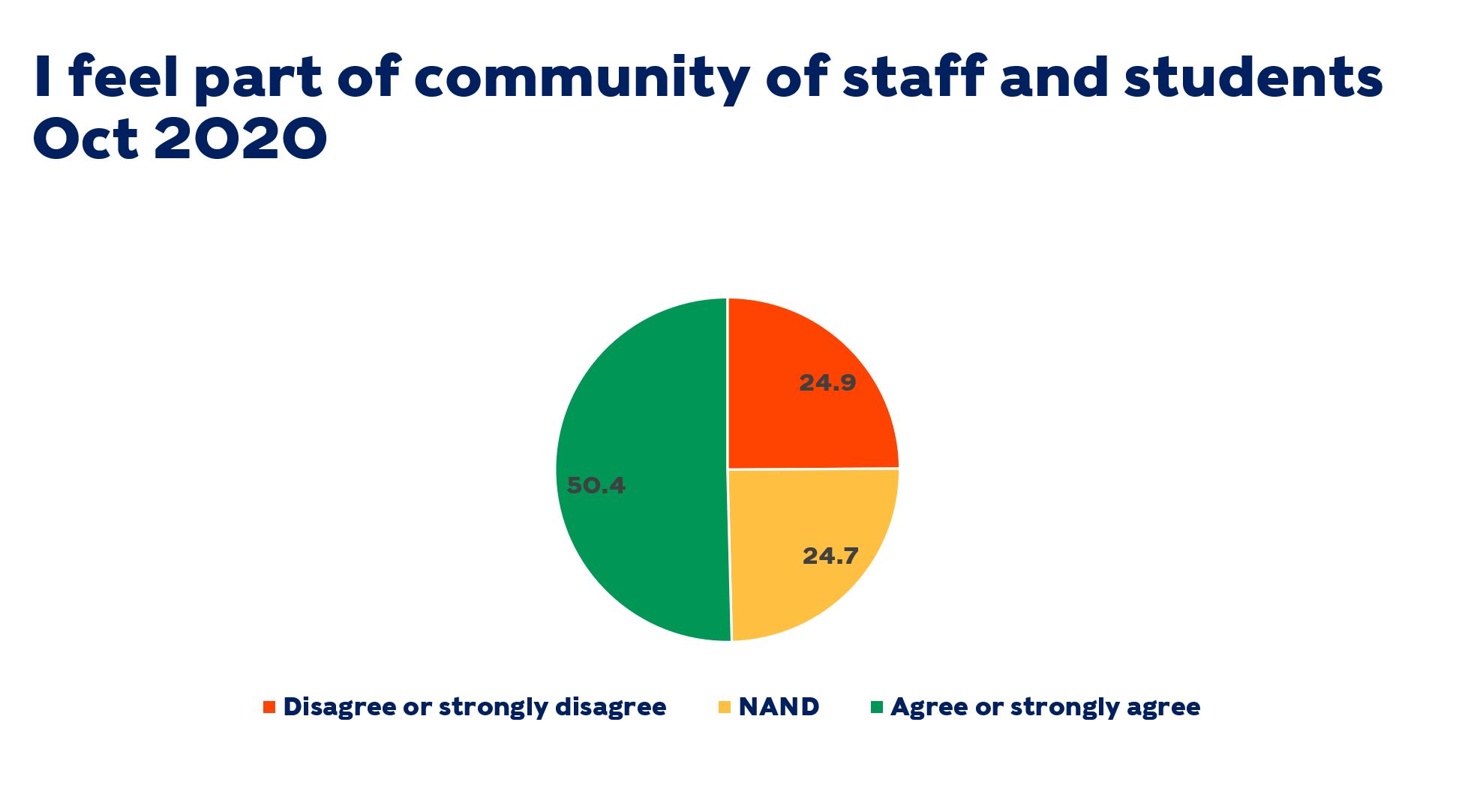

We know from our other research that belonging is crucial to academic success and staying the course, and our own research showed that students feeling part of a community (NSS question 21) is closely related to feelings of belonging, mental health perception and to outcomes confidence. So we asked the question again here, and again we saw a decline:

On the main issue of non-continuation, we wanted to know whether students were considering leaving their course, and if so how often. We used the term “dropping out” on advice from SU officers we consulted, who advised this is a commonly understood term:

To identify who was most “at risk” of leaving their course, we divided respondents into those who said “every day” or “every week”, which we have called here “at risk”, and respondents who said “less than weekly” or “never”, and we have called that group here “not at risk”.

We interrogated a series of diversity characteristics and identified groups more at risk than others:

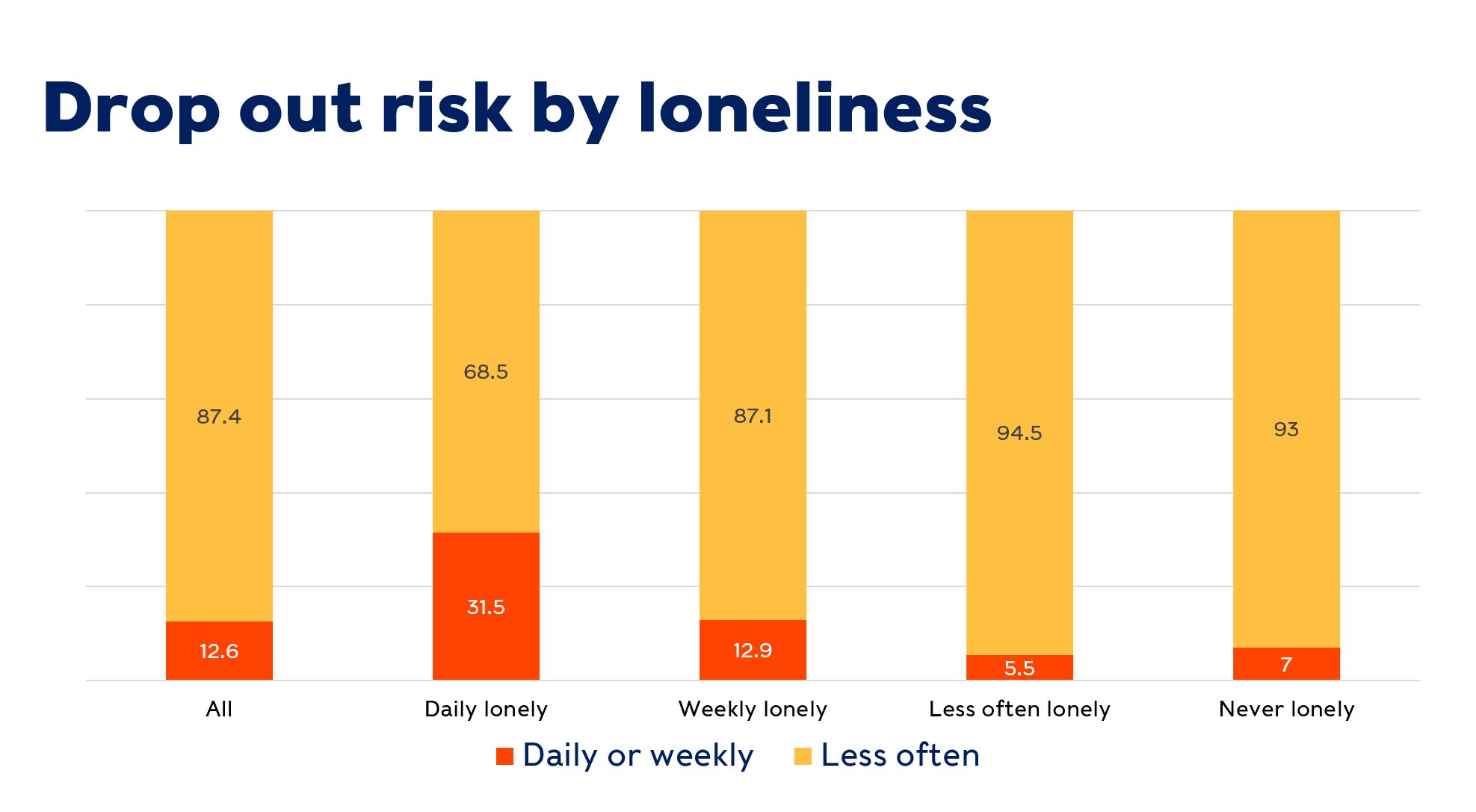

These match more general understandings on access and participation and priorities for student success work – although the international figure, and non-significant differences between ethnic groups were interesting. But perhaps the most significant relationships that we found were between non-continuation risk and other questions that surrounded happiness and loneliness:

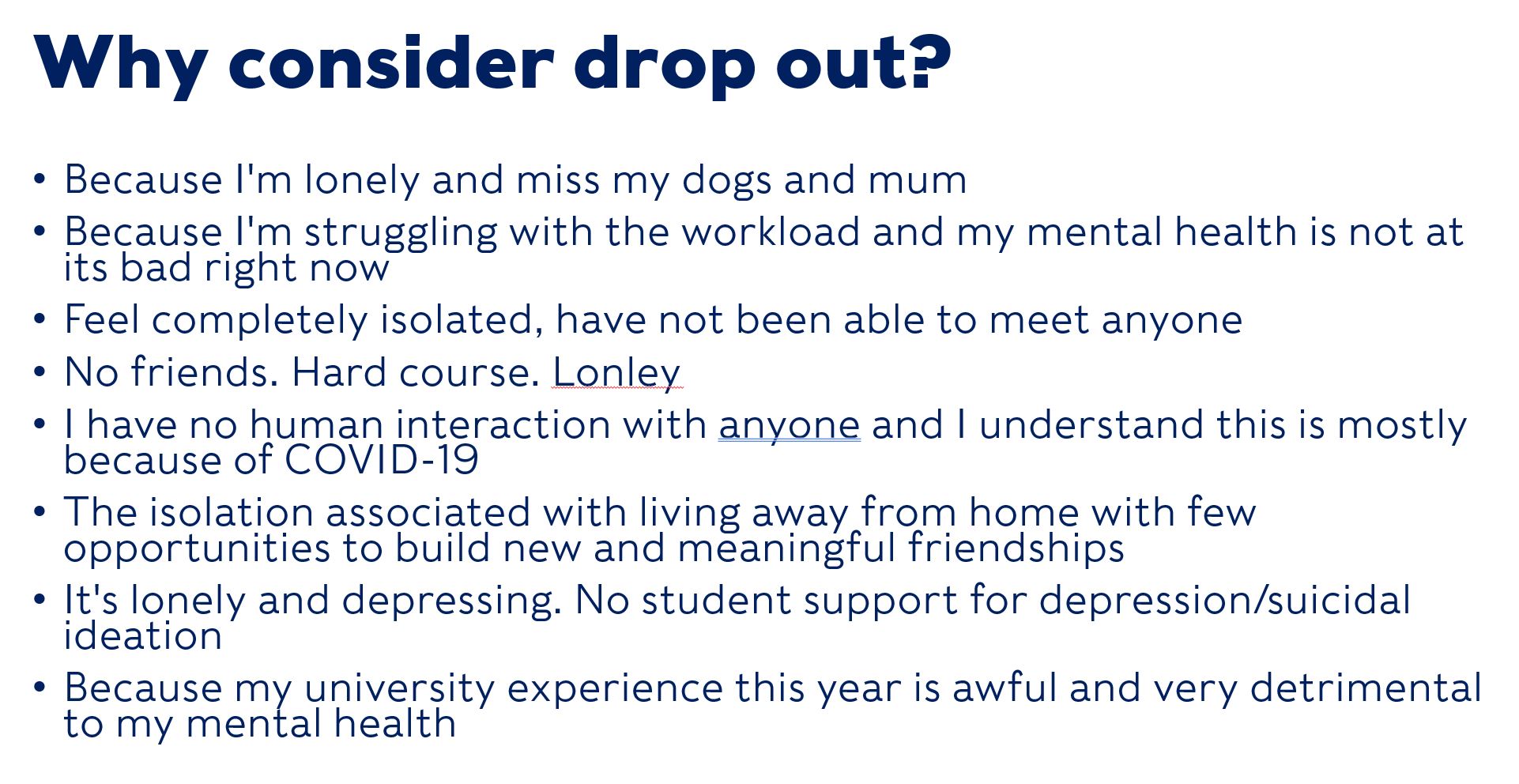

In the qualitative feedback, we asked why students responded the way they did – and we looked particularly closely at comments from students that said they were considering dropping out “every day” to see if we could identify themes. It is hard to overstate how often isolation and loneliness came up:

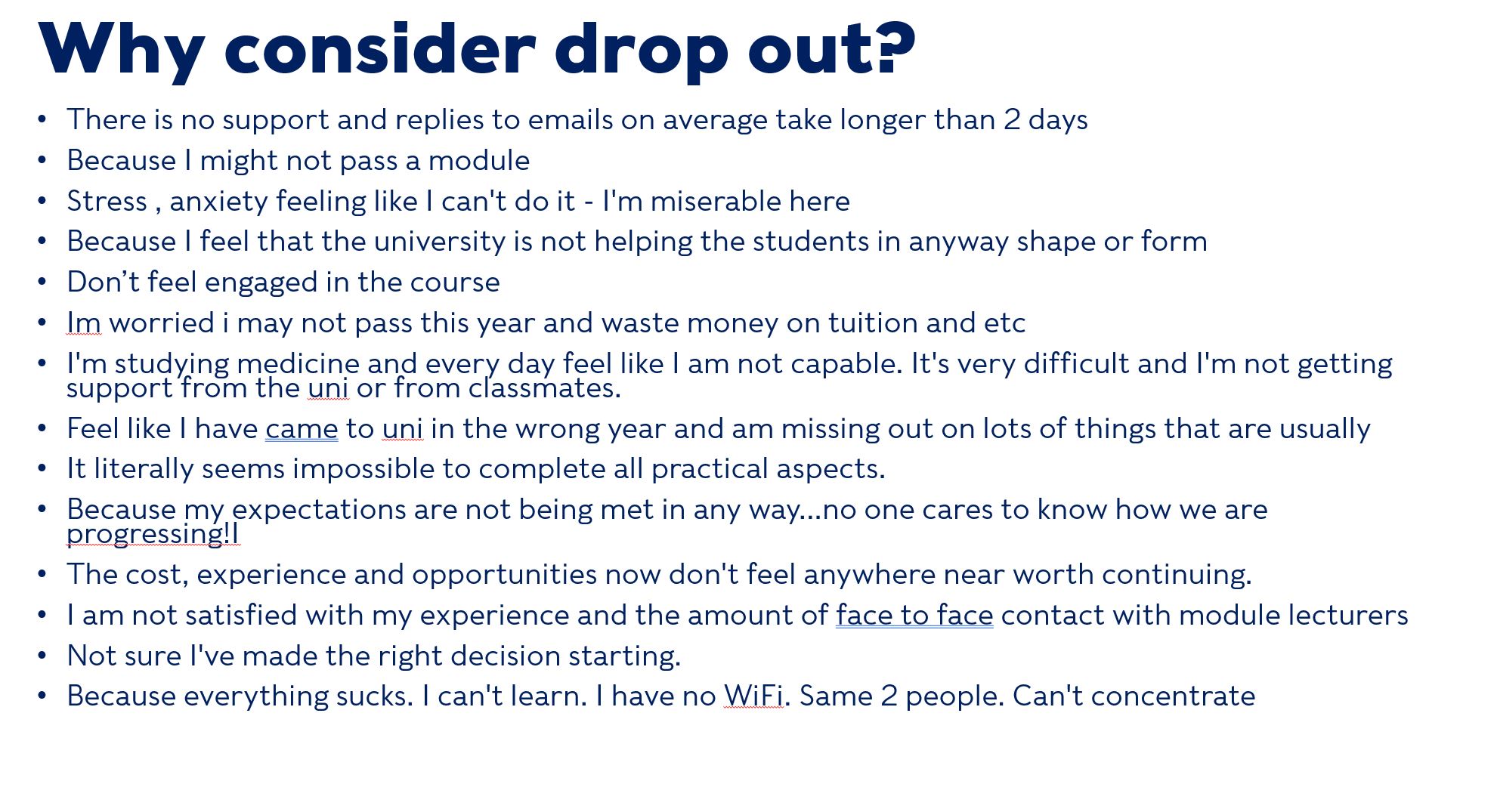

To the extent to which comments reflect other issues, low confidence in being able to obtain academic outcomes is common, as well as a strong sense from many students that they are missing out on what university should be or what it usually offers:

The student experience?

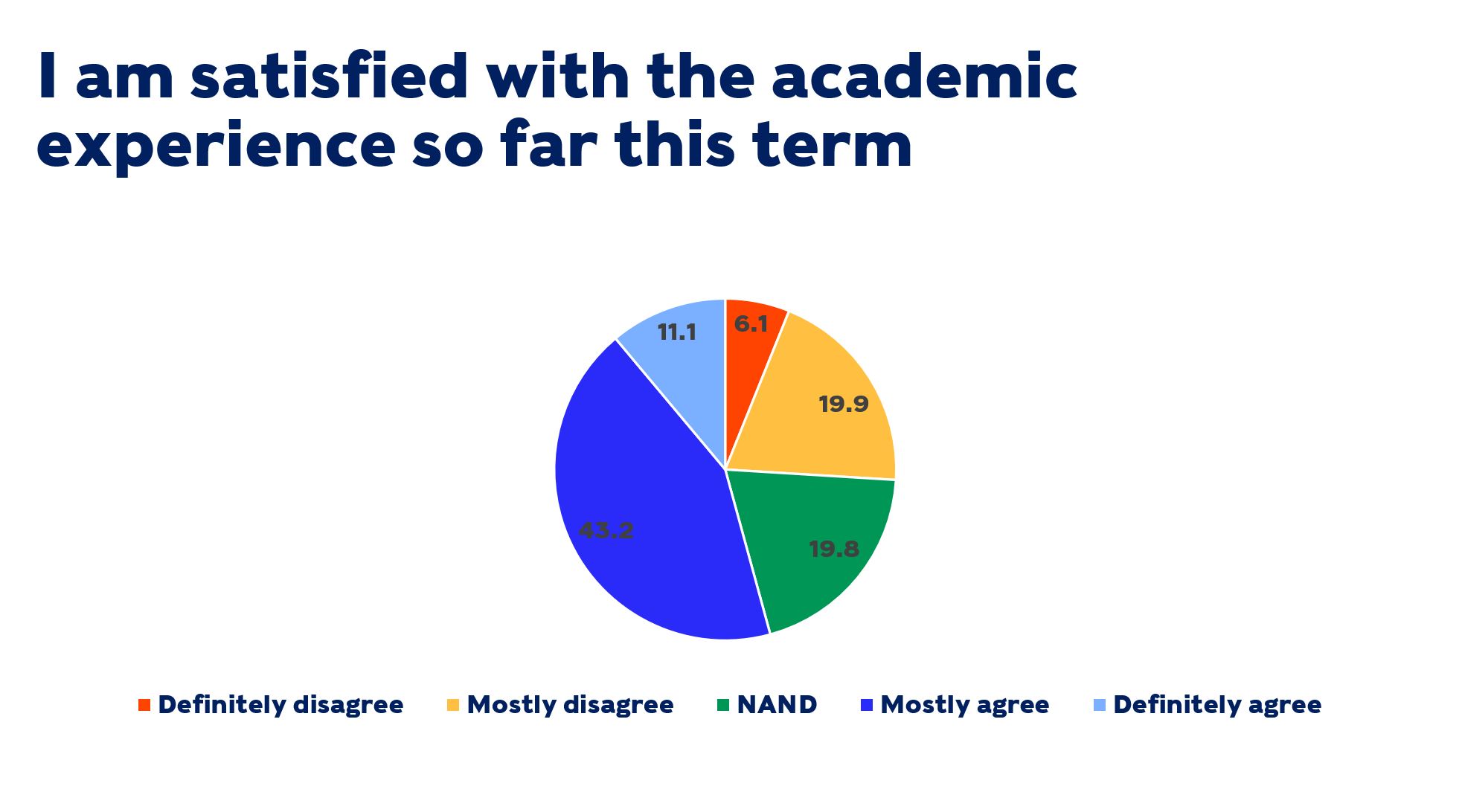

We also wanted to know about initial feelings of satisfaction with the academic experience. We might have reasonably expected early academic experience impressions to manifest in an increase in “neither agree nor disagree” – and one in five do respond in this way – but one in four actively disagrees:

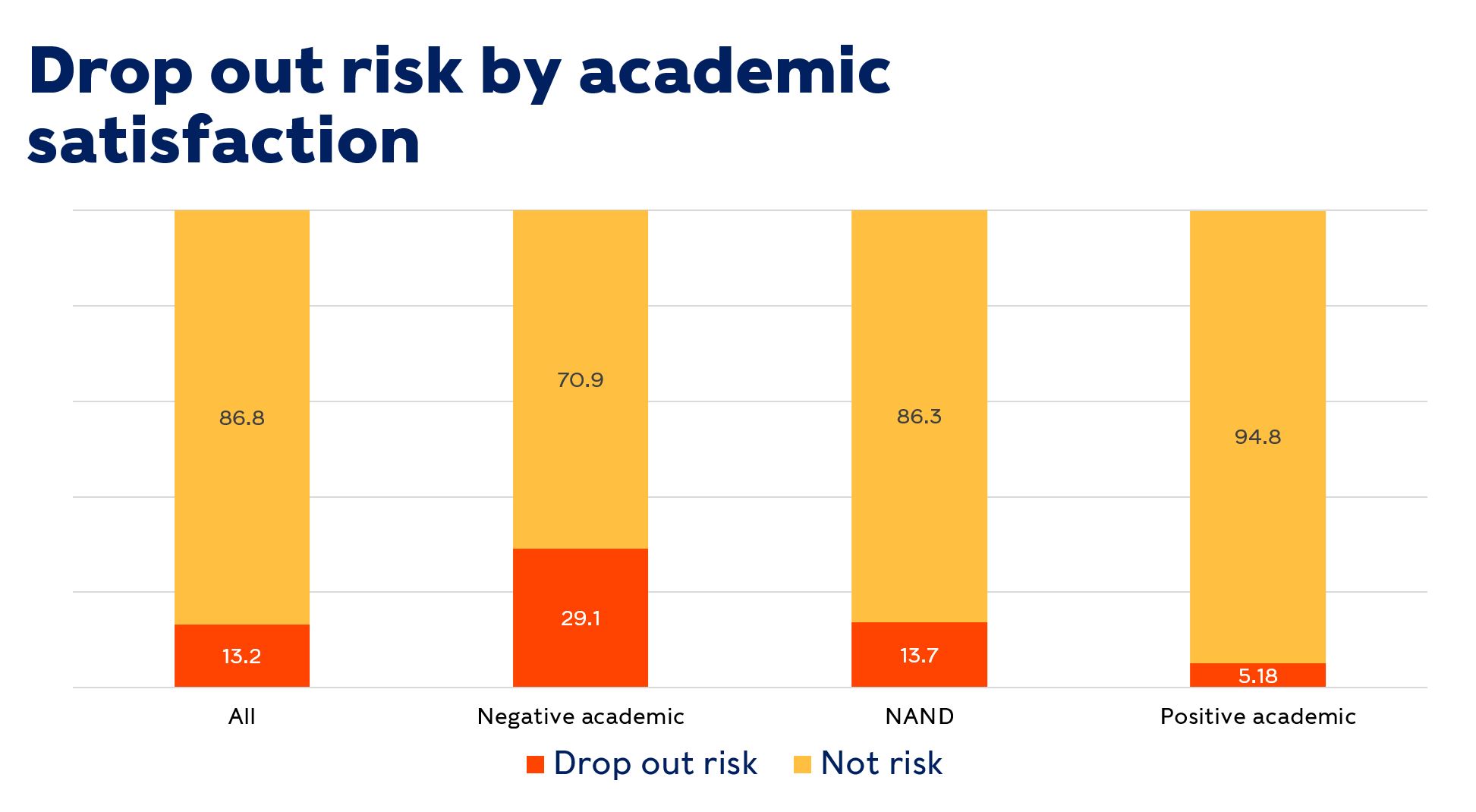

We then cross referenced (initial) satisfaction with those “at risk” of non continuation and found a clear relationship between the two:

When we asked why students had responded in the way that they had, a notable proportion of negative responses focused on not being able to access the learning; the way in which academic staff interact with students individually with support or answers to questions; several comments focus on facilities, or the mix between theory and practical activity: and many were dissatisfied with organisation and management issues like timetabling.

But most striking were the number of comments on what we might call the social aspects of learning – so many reflected dissatisfaction with the level of interaction with others being facilitated or even possible if the teaching was experienced asynchronously.

It is true that large number of dissatisfaction comments related to online learning – preferring face to face and being disappointed at the amount of face to face on offer. But a closer look suggests students that say they are dissatisfied with online teaching are not usually unhappy with it per se; they are unhappy at not being able to access it or unhappy that it fails to provide social interaction. And in a large number of cases there appear to be significant differences in approach to and quality of online teaching between modules/classes for individual students – a consistency problem.

Meanwhile those happy with online teaching praise the individual support they get from academic staff or interaction with peers. Even where students do express being unhappy with online teaching, they often contextualise that as problematic because they have moved unnecessarily to the local area to experience it, rather than the online teaching itself being of poor quality. The findings remind us how important the social aspects of learning are – and how difficult they have been to experience for many students so far this term.

We asked students to identify what providers or their students’ unions should do to tackle loneliness and support students who feel lonely at university during Covid-19. Those searching for a holy grail of innovation here may be disappointed – students were focused on simple ideas centred around human connection.

A large number of responses wanted more online activities to be proactively organised, often focussed around student identities, interests or courses. A huge proportion wanted to see safe activities put on in a face to face format. And some wanted proactive outreach – although we should not understate the emphasis in the comments on being allowed to and given support and space to interact with others safely.

What next?

There is little in the results that comes as a major surprise. In many ways, the pandemic and its impacts serve to accentuate and exaggerate previous research on student loneliness and its relationship to student confidence, achievement and mental health.

The progress of the pandemic at the time of writing will likely continue to pose a challenge to those seeking to take part in or organise face to face activity – be that academic, non academic or social. However that doesn’t mean that we can’t and shouldn’t attempt to learn from the feedback with particular reference to provision next term. There is much much more to be done to ensure that students’ experience is as social as they expect and need it to be to succeed.

Download the main results of the Don’t Drop Out survey.

We are particularly grateful to the students’ unions that made the work happen with us – big thanks to the SUs at Middlesex University, Queen Mary, University of London, Kingston University, University of Southampton, University of Sunderland, City University of London, University of Leicester, Bath Spa University, University of Bedfordshire, UEA, Bangor University, University of Manchester, UCLAN, Coventry University, Leeds Beckett University, University of Worcester, King’s College London, UCL, UEL, Canterbury Christ Church, UCB, St Marys University, Twickenham, Oxford Brookes University, Solent University, Southampton, University of Plymouth, University of Sheffield, University of Nottingham, and University of the Arts London.

Trendence is a leading student-focused market research firm in the UK and Ireland.

Feeling lonely and not being able to cope with it seems to be a major issue for many, I suppose I’m lucky I grew up in a different age where independence of thought, action and being able to live and work alone was more the norm.

Looking at the survey it seems having identifiable ‘intersectional’ definitions makes you more likely to A. be unhappy, and/or B. take such surveys, or is it simply ‘the loudest squeaking wheel gets the most oil’ effect?

Regarding “What could be done?”, I agree that these sorts of things would be beneficial to students. However, the average academic is already overworked, and in a poor position to be able to provide those things. So, who is expected to provide them? Perhaps each department needs a dedicated “student fun consultant” or something. Obviously we are edging nearer and nearer to treating students like children rather than adults, but perhaps that is a good thing.

These are just excuses…if you look at universities that did all these things, very poor engagement with them and many lecturers will tell you there is little to no interaction or participation in online lectures so what exactly is the problem? Likely an inability to simply cope in the real world.